Pasolini, with his usual prophetic gaze, was among the first to lucidly decipher the real scope of the telluric change that society was undergoing ab imis fundamentis. In particular, he understood how the consumer society was not only not founded on Christianity, but had to annul it in order to impose itself as the only permitted religion. When, in 1973, Italian cities were literally invaded by jeans billboards with the overtly desacralizing formula “you will have no other jeans but me,” Pasolini commented on the incident with a scathing article entitled “Linguistic Analysis of a Slogan.”

In particular, the photos used for the advertisement showed respectively: a female belly and blue jeans unbuttoned in a provocative way, accompanied by the inscription “you won’t have any other jeans but me;” and a woman’s butt with the slogan, “he who loves me follows me.” Finally, “Jesus jeans” was the name of the product advertised in such a disruptive way for the time. The Christian creed was twisted and manipulated to promote one of the many products of the new atheistic and consumerist creed of capitalist civilization which, precisely in those years, was abandoning its dialectical-bourgeois phase to move on to the absolute-post-bourgeois one. It was moving from a “market” society, still founded on religious auctoritas, to a “market” society, centered solely on the auctoritas of the commodity form which, as such, had to reduce everything—including religion itself—to the rank of circulating merchandise. The original Christian message was not only immanentized, profaned and deprived of its peculiar reference to the sphere of transcendence—with a synergistic movement, it was refunctionalized in a liberal-consumerist sense, evicting de facto the God of the Heavens and replacing Him with the new divinity of the markets and the cornucopia of goods marketed by it in the sphere of capitalist circulation.

In fact, Pasolini’s article does not dwell on the images used for the posters and, therefore, on the properly erotic aspect of the message, although “sexual consumerism” and bourgeois hedonism were undoubtedly themes he treated with precision elsewhere. In this case, Pasolin’s analysis is directed towards the words used in the posters and the messages conveyed by this rhetoric. The language of market civilization is homologized and hypersimplified, since it must be accessible to all in the reified form of a consumer good—the slogan thus stands as a privileged register of the culture industry and the society of spectacle, which reduces language itself to stereotyped and technified expressiveness. Every particularity and every nuance are destroyed for the benefit of an undifferentiated and homogenized subculture, which reduces and simplifies everything in the name of an apparent interclassism for qualitatively indistinct consumers. The civilization of capital justifies and promotes homologation by calling it “equality” while, paradoxically, making society increasingly unequal, subsumed under the alienating homologation of commodities.

Advertising expressiveness coincides with the abolition of all expressiveness. The new violent linguistic model, stereotyped and homogenized, has dissolved any kind of social and cultural diversification, so that it can become universal and usable by all. In the specific case of blue jeans, the advertisement uses, in the form of slogans, concepts and formulas taken from a deliberately distorted and profaned religious imaginary, in which Christ himself becomes a commercial brand, an expressive function of that one God—the Market, precisely—that consumer civilization recognizes and venerates. Although the billboards were quickly withdrawn by the public authorities, after an article of protest by Catholic institutions appeared in L’Osservatore Romano, the tendencies and coordinates of the future development of capital were fixed. The fabula docet has shown that the Church, which initially could have the illusion of being able to stop the advance of consumerist nihilism, would soon be overwhelmed until it disappeared, becoming itself an advertising brand among so many others. In Pasolini’s opinion, the Church was seriously mistaken, deluding itself with the possibility of being able to take advantage of the liberal-consumerist regime as it had taken advantage of the Fascist one. No equivalent of the Lateran Pacts was possible with the neo-Hedonist civilization of consumption. That led Christianity to its dissolution. The liberal-consumerist world, in fact, was ready to found itself on itself, on its own structural nothingness, freeing itself completely from the support of the Church, on which the empire of capital had also been founded up to that moment.

The previous bourgeois capitalism, which found one of its superstructural legitimacies in the Christian religion, and with it established that nexus of mutual recognition and support that culminated in the Lateran Pacts of 1929, was evolving towards a new figure: specifically, towards a post-bourgeois absolute capitalism of “nothing but commodities and nothing but consumers,” which was preparing to “give a free ticket” together with the bourgeoisie, also to the Christian religion. In Pasolini’s words, “fascism did not even scratched the Church, while today Neocapitalism destroys it.”

In the advertising poster for blue jeans, Pasolini was able to recognize one last piece of evidence to add in support of his thesis, according to which consumer civilization was even more totalitarian than fascism: the black shirt inside which the latter constrained bodies, unable to conquer souls, became superfluous in the alienated kingdom of consumerism, where the soul itself is controlled in a totalitarian way. If fascism had had to make a pact with the Church and with Christianity, trying to make use of both and, in any case, unable to get rid of them, the civilization of consumerism could now banish them definitively, profaning their symbols and their messages. Not only did the new liberal-consumerist hedonism of anarcho-capitalism for uninhibited consumers no longer need Christianity—it could easily mock and ridicule it, manipulating its vocabulary and imaginary in advertising form. There was no longer any need for an “alliance” between throne and altar, between religion and power, since consumerist power, intrinsically totalitarian, no longer needed it—it could itself also play the role of religion by “divinizing” its products, just as it had done with blue jeans advertised using the traditional Christian lexicon. From that moment on, the war declared by consumerism against the religion of transcendence and the Church itself was open and unstoppable, destined to pass through profanation and culminate in desacralization:

“In fact, there is no contradiction more scandalous than that between religion and the bourgeoisie, the latter being the opposite of religion… Fascism was a blasphemy, but it did not undermine the Church internally, because it was a false new ideology. The Concordat was not a sacrilege in the 1930s, but it is a sacrilege today, because fascism did not even scratch the Church, while today Neocapitalism destroys it. The acceptance of fascism was an atrocious episode; but the acceptance of bourgeois capitalist civilization is a definitive fact, whose cynicism is not only a stain, the umpteenth stain in the history of the Church, but a historical error that the Church will probably pay for with its decline.”

According to Pasolini’s analysis, the Church is guilty of having underestimated neocapitalism and of having failed to foresee the Epochemachend character of such a change (“a definitive fact”). The new power, in fact, has not limited itself to acting externally, finding a balance and an agreement with the altera pars. On the contrary, it has infiltrated the consciences and the weft of the social fabric, dominating and profoundly modifying them, triumphing where even the repressive and authoritarian power of fascism had failed. Pasolini recognizes in the particular case of the Jesus blue jeans slogan, the prodromal signs of a growing weakening of the institutions of the sacred, which are indignant and firmly opposed to offensive advertising posters, but which no longer really have the power to stop the advance of the new desacralizing spirit of consumerist nihilism.

This advance, which has barely begun, for Pasolini is destined to lead to the complete annihilation of Christianity—the Church seems doomed to lose its relevant role and to survive, in the best or worst of hypotheses depending on the point of view assumed, as a folkloric and ceremonial element, deprived of its own autonomy and capacity to colonize consciences and a society in a phase of de-Christianization. The fact that, in 1973, the blue jeans posters were withdrawn from circulation after the Church’s complaint, was only a momentary setback, in no way interpretable as a possible reversal of trend. The path of profanation and desacralization had already been taken and the coming years would only represent an acceleration of this process.

From another perspective it could be argued, following in Pasolini’s footsteps, that not even the historical communism of Noucentisme managed to eliminate the Church, at least not with the success that the radical atheism of consumer civilization is achieving. Suffice it to recall that Stalin himself, on the one hand, authorized the election of a patriarch in Moscow (demanding, however, the collaboration of the Orthodox Church with the political system) and, on the other hand, openly exploited religion as a national cement. Unlike fascism, which had to seek a compromise with the Church, and unlike communism, which is itself a secularized Church, which projected salvation into the immanent space of classless society, absolute-totalitarian capitalism—and it alone—has no internal or external need for religion and the Church: it has no “internal” need for either, because it is based on a complete relativistic nihilism and is, in this respect, self-sufficient and thus intrinsically hostile to the idea of truth, both in its philosophical and its religious sense; moreover, it has no “external” need, since its power is now so persuasive, omnipresent and unrestrained that it no longer has to depend on the support of other forces that have not yet been subdued.

In accordance with the process already observed by Pasolini, the new nexus that characterizes the regime of capital absolutus in its ultimate evolutions, takes shape according to the inclined plane that leads the Catholic religion itself to desacralization and perverse friendship, and in a subordinate position, with the consumerist regime. “The case of the ‘Jesus’ jeans,” wrote Pasolini, “is a sign of all this,” of how the new power—no longer clerical-fascist, but hedonistic and consumerist—can now discard spiritual power: “Power has no more need of the Church, and consequently abandons it to itself.” In fact, Pasolini writes again, “the world has overtaken the Church;” it has gone even further.

Pasolini saw in action the assault on heaven, undertaken by the market system not only in the jeans ad, but also in the partisan figure of Christian Democracy (CD). In it, the reference to the Church and to transcendence was, in fact, purely nominal, since it was a party totally integrated in the new immanentist order of pragmatically capitalist power. With CD—it is argued in the Lutheran Letters—”the Catholic votes will finally be Christian democratic; that is, no longer guaranteed and managed by the Catholic Church, but directly by the economic Power,” which can still formally, for the sake of convenience, call itself Christian. And Pasolini continues: “deprived of any shadow of political thought, Christian Democracy has governed according to the pragmatic—and therefore evidently mimetic, generic and inert—models of Western capitalism: devilishly mixing these models with those of the spiritual models of the Church.”

In short, with CD and its liquid atheism, a political force becomes operative that uses the call to transcendence as a simple instrument to hide and legitimize its own integral adhesion to the model of capitalism on the part of the masses still educated in a Christian sense. It is according to this hermeneutic key that the so-called “defeat” of that anomaly that was the pontificate of the recently deceased Ratzinger, accused of not assimilating and not being in tune with the new marketing of a Catholicism without transcendence and without a theological vocation, can be interpreted. By way of synthesis, as I have tried to demonstrate extensively in my book, La fine del cristianesimo. La morte di Dio al tempo del mercato globale e di Papa Francesco (2023) (The End of Christianity. The death of God in the Time of the Global Market and Pope Francis), the “crossroads” prophesied by Pasolini are currently embodied, on the one hand, by Ratzinger’s Church, which resists the nothingness of consumer civilization and does so by defending tradition and transcendence; and, on the other hand, by Bergoglio’s post-Christian and liberal-progressive neo-church, which dissolves Christianity into low-cost faith and smart masses, effectively causing the suicide of Christianity to which Pasolini alluded.

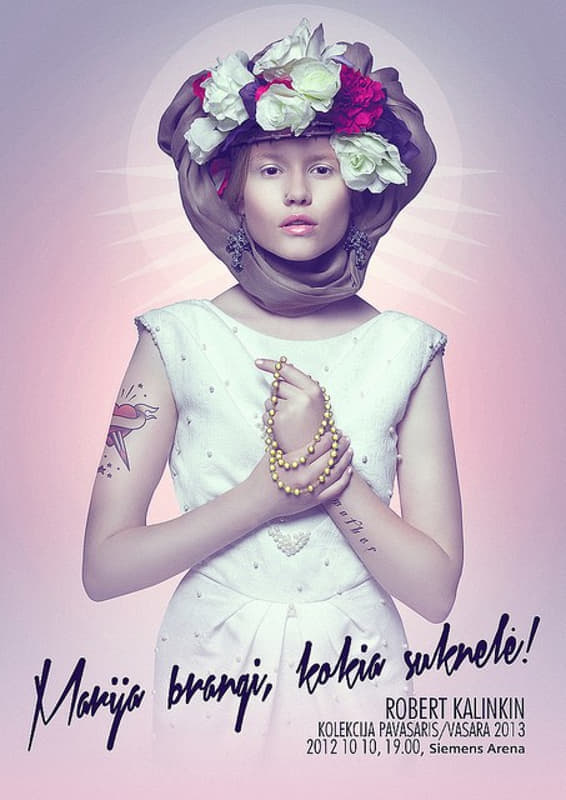

In confirmation of Pasolini’s prophecy may be cited, among other cases, a 2012 judgment of the European Court of Human Rights. The Court legitimized and upheld the use of religious symbols in advertising. Specifically, a Lithuanian company had used the image of Jesus and Mary to sponsor its new clothing line, receiving a fine for it—this judgment was judged by the European Court as harmful to the freedom of expression of the company itself.

With this, Pasolini’s prophecy can be considered fulfilled: the Christian Jesus has been defeated in the confrontation with the capitalist Jesus. The new spirit of hedonistic and desacralizing capitalism, ready to mutate the divine itself into an advertising strategy, was already implicit in that apparently provocative and easily neutralized slogan, which Pasolini had been able to decipher with prophetic lucidity and which today, in the post-1989 world, multiplies hypertrophically in a kaleidoscopic variety of posters and advertisements, representing in fact the new symbolic system within which Western man moves in integral reification. It is for this reason that, again according to Pasolini’s analysis, the new spirit of power, which at first had shown itself to be “competitive with the religious,” was destined to “take its place in providing men with a total and unique vision of life,” stripped of all sacredness and of all connection with the reasons of the soul and with the regions of the eternal.

Diego Fusaro is professor of History of Philosophy at the IASSP in Milan (Institute for Advanced Strategic and Political Studies) where he is also scientific director. He is a scholar of the Philosophy of History, specializing in the thought of Fichte, Hegel, and Marx. His interest is oriented towards German idealism, its precursors (Spinoza) and its followers (Marx), with a particular emphasis on Italian thought (Gramsci or Gentile, among others). he is the author of many books, including Fichte and the Vocation of the Intellectual, The Place of Possibility: Toward a New Philosophy of Praxis, and Marx, again!: The Spectre Returns. [This article appears courtesy of Posmodernia].

Featured: Sekmadienis Ltd poster (2012). Slogan reads: “Dear Mary, what a dress!”