The paired concept of “Iran” and “Turan” has undergone many modifications in history. Its classical use is associated with the medieval Persian epic, in particular, with Firdausi, where “Iran” was understood as a state of sedentary farmers, and “Turan” as a world of nomads of Central Asia (in antiquity—Iranian-speaking, and since the 6th century A.D.—Turkic-speaking and Mongol-speaking). As applied to antiquity, it was thus a question of the opposition between the Western Iranian and Eastern Iranian (in the linguistic sense) worlds.

At the beginning of the 20th century the meaning of the term “Turan” was radically changed by such pan-Turkists as Yusuf Akchurin and Ziya Gokalp. Starting from 1911-1912 on the wave of the Young Turk revolution, they began to understand “Turan” as the totality of Turkic-speaking peoples far beyond the historical Turan (Central Asia). In 1923 Gokalp published the book, Basic Principles of Turkism, thus completing the process of creating the myth of Turan opposing both the Aryan and Arab worlds.

By this time, the Eurasian movement had emerged and was gaining strength in the Russian emigration, whose leaders N.S. Trubetskoy and P.N. Savitsky opposed Pan-Turkism, contrasting it with the idea of the historical and geographic unity of the peoples of Russia-Eurasia. With this approach, the nomads of the steppes (Kazakhs) and sedentary Turks of the Volga region (Tatars) were inextricably linked with the Russian world, and the Turks of Anatolia—with the Greek, Balkan, Mediterranean world [Трубецкой Н.С. О туранском элементе в русской культуре // Трубецкой Н.С. История. Культура. Язык. М.: Прогресс, 1995. С. 141–161—N.S. Trubetskoy, “On the Turanian element in Russian culture,” in N.S. Trubetskoy, History. Culture. Language (Moscow: Progress, 1995), pp. 141-161.].

However, the intermediate position of Central Asia in such a scheme remained uncertain and caused Eurasians a sense of discomfort. Against the background of the creation in 1924 of the Soviet Union republics, primarily Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, it was necessary to determine whether this region belonged to Russia-Eurasia, Turan or Iran as a place of development. At first, however, Eurasianists had no experts on Iran and Central Asia. They could rely on the old works of V.I. Lamansky on the borders of the “middle world of Asia-European continent,” but even in them the southern border of the Russian, Eurasian world was defined extremely vaguely, mainly on the border of the Russian Empire with Afghanistan, along the ridges of the Hindu Kush and Tibet [Ламанский В.И. Об историческом изучении греко-славянского мира в Европе // Ламанский В.И. Геополитика панславизма. М.: Институт русской цивилизации, 2010. С. 86.—V.I. Lamansky, “On the Historical Study of the Greek-Slavic World in Europe,” in V.I. Lamansky, Geopolitics of Pan-Slavism (Moscow: Institute of Russian Civilization, 2010), p. 86.].

Luckily for the Eurasianists, there came along Vasilii Petrovich Nikitin (1885-1960), an experienced Orientalist, diplomat, and Iranianist. From 1912 to 1919, he worked in the Russian consulates in Persia, even headed them, was closely acquainted with the lives of the Kurds and Assyrians and their leaders, participated in the events of the First World War on this front. After the Revolution he emigrated to Paris and never returned to his homeland. Working for thirty years in a French bank, he devoted his free time to writing scientific works on Orientalism, gained recognition among French Orientalists, and became a member of various academies and scientific societies. While still in Russia, he married a Frenchwoman, which allowed him to easily enter the circle of the French ultra-right and traditionalists, the first among Russian emigrants to read and popularize the works of René Guénon.

Nikitin at various times wrote about India, China, Japan, even Poland, but he always focused on the people of Iran. After his death, his fundamental work on the Kurds was published in the Soviet Union [Никитин В.П. Курды. М.: Прогресс, 1964.—V.P. Nikitin, The Kurds (Moscow: Progress, 1964).]. Therefore, Eurasians were immediately interested in him as an Iranianist. At the first meeting with Nikitin on September 24, 1925, the leader of the Eurasian movement, N.S. Trubetskoy, asked him to write a major article on Russia, Iran and Turan in order to define the boundaries between them. Nikitin recorded a summary of his conversation with Trubetskoy: “Our Turanism interferes with Iranism and frightens it (big and small Turan).” [Сорокина М.Ю. Василий Никитин: Свидетельские показания в деле о русской эмиграции // Диаспора: новые материалы. Вып. 1. Париж – СПб.: Athenaeum-Феникс, 2001. С. 603.—M.Y. Sorokina, “Vasily Nikitin: Witness testimony in the case of Russian emigration,” in Diaspora: Novye materialy, Vyp. 1, Sankt-Petersburg–Paris 2001, p. 603].

The Eurasianists needed clarification of the concept of Turan in order to allow their ideology to spread among the Turkic-speaking peoples of the USSR. Nikitin actively took up the work, and by the end of the year he finished the article, and on January 4, 1926 he received a visit from P.P. Suvchinsky, who praised it [Sorokina (2001), p. 606]. This topic also aroused the interest of other Eurasians; in particular, L.P. Karsavin asked Nikitin: “Can a Persian become Russian? What would happen to Christianity if the Persians adopted it? After all, from Zoroastrianism, not without reason, they have deviated into “Satanic” Manichaeism.” [Sorokina (2001), p. 602].

Between January 1926 and September 1929, Nikitin published 24 of his articles in Eurasian publications. Many of them were devoted to the general justification of the need to intensify Soviet Russia’s policy in Asian countries, but a number of works dealt specifically with Persia, its relations with Russia before the revolution, during World War I, and at the present moment under the regime of Reza Shah Pahlavi.

[Никитин В.П. 1) Персия в проблеме Среднего Востока // Евразийская хроника. Вып. 5. Париж, 1926. С. 1–15; 2) Ритмы Евразии // Евразийская хроника. Вып. 9. Париж, 1927. С. 46–48; 3) По Азии. Сегодняшняя Персия // Евразийская хроника. Вып. 9. Париж, 1927. С. 55–60; 4) [Рец.:] Свентицкий А.С. Персия. РИОБ НКВТ. М., 1925; Корецкий А. Торговый Восток и СССР. Прометей, 1925 // Евразийская хроника. Вып. 10. Париж, 1928. С. 86–88; 5) Россия и Персия. Очерки 1914–1918 гг. // Евразия. 1929. 6 апреля. № 20. С. 5–6; 13 апреля. № 21. С. 5; 20 апреля. № 22. С. 5; 27 апреля. № 23. С. 6–7; 4 мая. № 24. С. 6; 1 июня. № 28. С. 7–8; 6) Персидское возрождение // Евразия. 1929. 29 июня. № 30. С. 5–6; 10 августа. № 33. С. 6; 7 сентября. № 35. С. 6–7.—V.P. Nikitin, “Persia in the Problem of the Middle East,” in Eurasian Chronicle, Vol. 5 (Paris, 1926), pp. 1-15; “Rhythms of Eurasia,” in Eurasian Chronicle. Vol. 9 (Paris, 1927), pp. 46-48; “Across Asia. Today’s Persia,” in Eurasian Chronicle, Vol. 9 (Paris, 1927), pp. 55-60; Review: A.S. Sventitsky, Persia (RIOB NKVT. M., 1925); A. Koretsky, Trade East and the USSR (Prometheus, 1925}, in Eurasian Chronicle, Vyp. 10. (Paris, 1928), pp. 86-88; “Russia and Persia. Sketches of 1914-1918,” in Eurasia 1929: (April 6), № 20, pp. 5-6; (April 13), № 21, p. 5; (April 20), № 22, p. 5; (April 27), № 23, pp. 6-7; (May 4), № 24, p. 6; (June 1), № 28, pp. 7-8; “Persian Revival,” in Eurasia 1929: (June 29), № 30, pp. 5-6; (August 10), № 33, p. 6; (September 7), № 35, pp. 6-7.

In addition, Nikitin made oral presentations on Iranian topics at Eurasian seminars in Paris. [Татищев Н. Евразийский семинар в Париже // Евразийская хроника. Вып. 7. Париж, 1927. С. 44.—N. Tatishchev, “Eurasian Seminar in Paris,” in Eurasian Chronicle, Vyp. 7. (Paris, 1927), p. 44].

The above-mentioned article “Iran, Turan and Russia,” the preface to which was written by P.N. Savitsky, stands out among these essays in terms of its conceptuality. [Никитин В.П. Иран, Туран и Россия // Евразийский временник. Книга пятая. Париж: Евразийское книгоиздательство, 1927. С. 75–120.—V.P. Nikitin, Iran, Turan and Russia, in Eurasian Times. Book Five (Paris: Eurasian Book Publishers, 1927), pp. 75-120].

It won such popularity that it was a success even more than thirty years later. Nikitin by this time gave out all its reprints and was glad when P.N. Savitsky, in November 1959, sent copies to the students in the USSR [Sorokina (2001), p. 643].

How was the problem of the definition of Turan in this work handled? Savitsky recalled the cooperation between Russia and Iran in the Middle Ages, but at the same time he refused to include Iran in the place-development of Russia-Eurasia. In his opinion, “internal Iran” is an Asian country and for centuries fought the Scythian-Sarmatian nomads of the Eurasian steppes as representatives of “external Iran.” Recognizing a certain Iranian contribution to the formation of the Russian people, Savitsky still considered this contribution to be small [Editorial note of P.N. Savitsky. See, Nikitin, Iran, Turan and Russia, pp. 75-78.].

Nikitin looked at the problem quite differently. According to him, Russia and Iran are in a similar position at the crossroads of civilizations, and the Russian national character combines in itself Turanian and Iranian traits. The Turanian character is known from the works of N.S. Trubetskoy (it is a warrior, alien to abstract philosophy, hardy, loyal, passive). But Nikitin also pointed to the other pole of the Russian soul—the Iranian, represented in individualism and mysticism of the Old Believers, sectarians, Khlysts, preachers in general [Nikitin, Iran, Turan and Russia, pp. 79-80.]. The scientist viewed the history of Eurasia as a dialectic of the struggle of Iran and Turan, their ebb and flow. He later added to his article with three hand-drawn maps, showing how the concept of Turan expanded over the centuries until it encompassed both the steppe zone and agricultural Central Asia (Maverannahr) [Nikitin, Iran, Turan and Russia, pp. 118-120.]. Nikitin referred to the works of another Eurasianist P.M. Bicilli on the attempted alliance of Byzantium with the Turkic Khaganate against Sassanian Iran as a typical manifestation of the struggle between the two Eurasian principles [Бицилли П.М. Восток и Запад в истории Старого Света // На путях: Утверждение евразийцев. Книга 2. Берлин, 1922. С. 320–321.—P.M. Bicilli, “East and West in the History of the Old World,” in On the Roads: The Assertion of Eurasians. Book 2. (Berlin, 1922), pp. 320-321.].

Considering the history of Iran’s wars with nomads over many centuries, the researcher drew attention to the lack of study of Russian-Iranian ties and mutual influences [Nikitin, Iran, Turan and Russia, pp. 103-115.]. “There is a Turanian yarn in this Iranian-Russian canvas,” he concluded [Nikitin, Iran, Turan and Russia, pp. 113.].

He summed up: “The place of Russia between Iran and Turan has also been indicated…. Under the Mongol yoke both Rus and Iran were on an equal position of subordination to the Turan ulus. After liberation from this yoke, Rus and Iran went their own ways, as a result of which Rus took in relation to Iran the geographical position of Turan, whereas on the Bosporus, the statehood of Turanian root strengthened” [Nikitin, Iran, Turan and Russia, pp. 115.]. Nikitin reinforced this political conclusion with a reflection on the need for self-discovery of the Russian character with its duality of Turanian and Iranian traits: “Turan in our mental stock is an articulate, ‘kosher’ beginning, whereas Iran is individualism, in a form that reaches the point of rebellion, of anarchy” [Nikitin, Iran, Turan and Russia, pp. 116].

Marlène Laruelle, analyzing the reasons why Trubetskoy and Savitsky had asked for a detailed study of Iran and Turan from Nikitin, suggests that “the sedentary Central Asia… presented a problem for Eurasian thought,” that “the borders with Asia remained… blurred, and the movement failed to capture all the original and imagined potential that the claims of the Timurid and Mongol heritage carried within them” [Laruelle, pp. 172-173]. Therefore, according to Laruelle, “Eurasianism will remain indecisive about the sedentary peoples of Central Asia all the time” [Laruelle, p. 173]. These conclusions, in view of the above, do not seem quite accurate, and it is unlikely that the formula proposed by Laruelle can follow directly from the analyzed works of Nikitin, Savitsky, Trubetskoy, and Bicilli: “China embodies Asia; Persia is the outer East in relation to Russia; Turan is its inner East” [Laruelle, p. 177]. Nikitin himself nowhere distinguished between “East” and “Asia,” but always ranked Iran alongside India, China, and “Mediterranean Turkey” as civilizations that were Asian rather than Eurasian.

In his later Eurasian articles, Персидское возрождение [The Persian Renaissance (1929): Никитин В.П. Персидское возрождение // Евразия. 1929. 29 июня. № 30. С. 5–6; 10 августа. № 33. С. 6; 7 сентября. № 35. С. 6–7.—Nikitin, “Persian Revival,” in Eurasia. 1929: (June 29), № 30, pp. 5-6; (August 10), № 33, p. 6; (September 7), № 35, pp. 6-7.]—Nikitin put forward the thesis that, contrary to supposed apathy, cultural life in Iran never died, began to revive rapidly from the middle of the 19th century and reached a new level after 1925 under Reza Shah Pahlavi. The scholar talked about the general rhythm of Russian and Iranian history, from the fall of the Safavids and the Persian campaign of Peter the Great to the revolutionary events of the first quarter of the 20th century in both countries. Nikitin expressed the hope that the St. Petersburg period of Russian history, with its Westernizing intellectuals who did not want to understand Asia, was over. The duties of man to God instead of rights, the collectivism of the people instead of democracy and citizenship were what, in Nikitin’s opinion, united Russia with the Islamic world. The researcher hoped that “through the joint efforts of the Eurasian and Persian nationalities and the Moscow and Tehran authorities, ways would be found for a new politics and culture beyond imitation and dependence on imperialism and capitalism of the West and America” [Eurasia, 1929: (June 29), № 30, p. 5.]. At the same time Nikitin did not abandon the Eurasian slogans “about demoticism, about ideocracy, about the labor state and the common cause” [Eurasia, 1929: (June 29), № 30, p. 6]. The scholar presciently anticipated the future ideas of Khomeini and the Islamic revolution, pointing out the necessity for Iran to develop a new state system: not parliamentarism and not absolutism, but a combination of the Shiite principle of “light-bearing” Imamate and modern conditions [Eurasia, 1929: (August 10), № 33, p. 6].

Nikitin drew particular attention to the ease of mutual understanding between Russian and Persian peasants and merchants, the “osmosis” between them, and the rapidity of Russian settlement in Iran.

Nikitin predicted the “rise of national energy” in Persia, expressed already by the end of the 1920s in that country gaining full political independence, active construction of railroads, improvements in agriculture, and the development of new fields, all with German and Soviet support. In the field of religion and culture, the scholar noted in contemporary Iran a “feverish” surge of enthusiasm for Zoroastrianism, the neo-pagan reconstruction of the Sassanid era, Babism, and renewed Shiism. He noted the gravitation of Iranian thought towards an identity as opposed to the imitative nature of the Turan, described earlier by N.S. Trubetskoy [Eurasia, 1929: (September 7), № 30, p. 7].

Thus, according to the Eurasianists of the 1920s, Iran (the West Iranian peoples) opposed the steppe, nomadic Turan (the East Iranian, and later Turkic peoples). And that Russia is a direct heir of Turan, but it should choose the path of active foreign policy and cooperation on an equal basis, and the harmonization of development and revolutionary revival of Russia and Iran, rather than confrontation with Iran (as well as with India and China), as it was in the times of nomadic raids.

As for Turan, under such an interpretation, covering not only the Kazakh steppes, but also the sedentary Central Asia, it was included in the Eurasian place-development, becoming an integral part of Russia.

Thus, Eurasianists, with their historical and geographical arguments, knocked out any ground from under the pan-Turkic understanding of the myth of Turan as a set of only Turkic-speaking “descendants of the wolf” opposed to all other peoples of Eurasia. Nikitin specifically stipulated that the “Pan-Turan idea” in Turkey and Hungary was “a phenomenon of the intelligentsia’s mugshot and a certain literary fashion” [Никитин В.П. По Азии (Факты и мысли) // Версты: Вып. 1. Париж, 1926. С. 241.—V.P. Nikitin, Across Asia. Facts and Thoughts, (Paris, 1926), p. 241.] This formulation of the question is not only of academic interest but also sounds very relevant nowadays, when the ideology of pan-Turkism is supported by the elites of Turkey and Great Britain, and the convergence of the Eurasian Union, headed by Russia and the Islamic Republic of Iran, has reached a qualitatively new stage.

Maxim Medovarov, PhD, is at Department of Historical Methods and Informatics, Nizhny Novgorod State University. This article appears through the kind courtesy of Geopolitica.

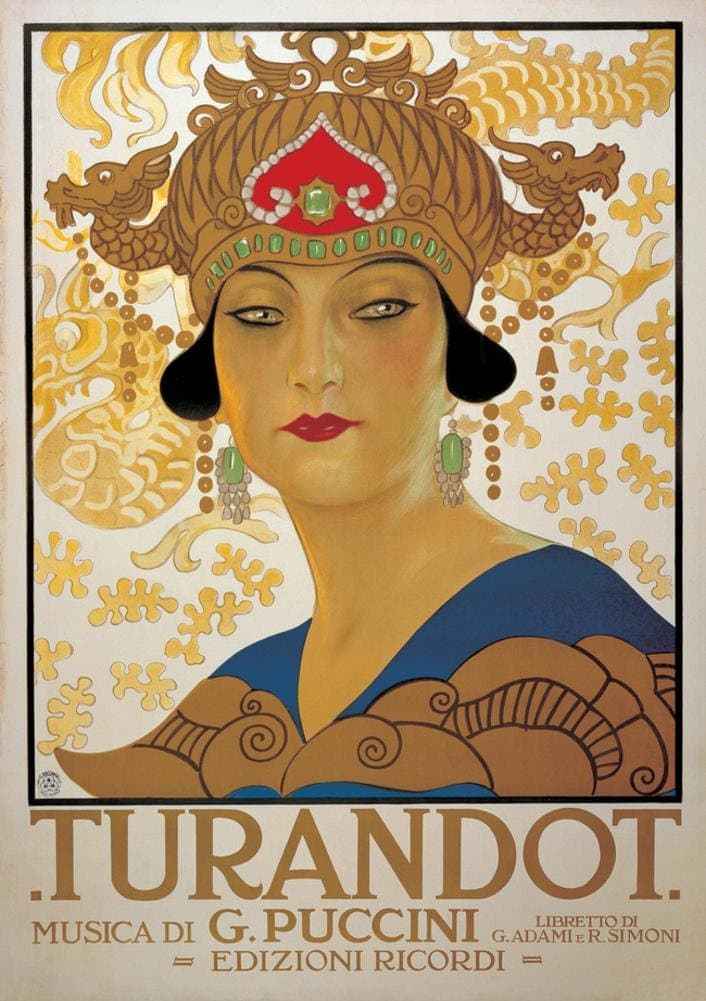

Featured: Promotional poster for Giacomo Puccini’s opera “Turandot” (“Daughter of Turan”), April 25, 1926.