The first Iranian cinema spectator (1897 AD). and the first Cinematograph theater in Iran: 21 November to 20 December 1903.

As such eminent scholars as Farrokh Ghaffari and Jamal Omid have shown in the past, an Iranian‘s initial acquaintance with the cinema is first mentioned in Ebrahim Sahhafbashi‘s memoirs.

Ebrahim Sahhafbashi (Mohajer) Tehrani was born around 1858 and died in 1921 or 1922, at the age of 63, in Mashhad His full name has been copied from a note of his reproduced below his portrait in Name-ye Vatan, and his birth and death dates are approximations provided by his son, Abolqassem Reza‘i. He was fascinated with new technologies and inventions and his trade of eastern Asian goods took him several times across the world. He was a liberal-minded modernist and rather nonconformist in his clothing. Undoubtedly, following the first cinematographic representation in Paris in 1895, and soon after that in London, Iranians living in Europe at the close of the nineteenth century were able to see various films, but since no writings from them remains—or has come to light—the first spectator (as he is called today) must be considered to have been Ebrahim Sahhafbashi, in London, seventeen months after the first public representation in Paris.

He writes in his memoirs:

Yesterday, at sunset I took a walk in the public park… [In the evening] I went to the

Palace Theater. After song and dance performances by ladies [… and a show of acrobatics, etc., I saw] a recently invented electric device by which movements are reproduced exactly as they occur. For example, it shows the American waterfalls just as they are; it recreates the motion of marching soldiers and that of a train running at full speed. This is an American invention. Here all theaters close one hour before midnight.

Sahhafbashi was mistaken as to the cinema‘s country of origin, perhaps because the film he saw was American, as his reference to the Niagara Falls seems to indicate. There is no reason to believe that Sahhafbashi‘s interest in cinema, during his first encounter with it, went beyond that of a mere spectator, but it is also probable that the thought of taking this invention to Iran crossed his mind, although this is never mentioned in his writings.

According to sources known to the present, he was the first person to create a public cinema theater in 1903, eight years after the invention and public appearance of the cinema in France, six years after Sahhafbashi‘s seeing the cinema in London, and three years after the arrival of cinema equipment to the Iranian court.

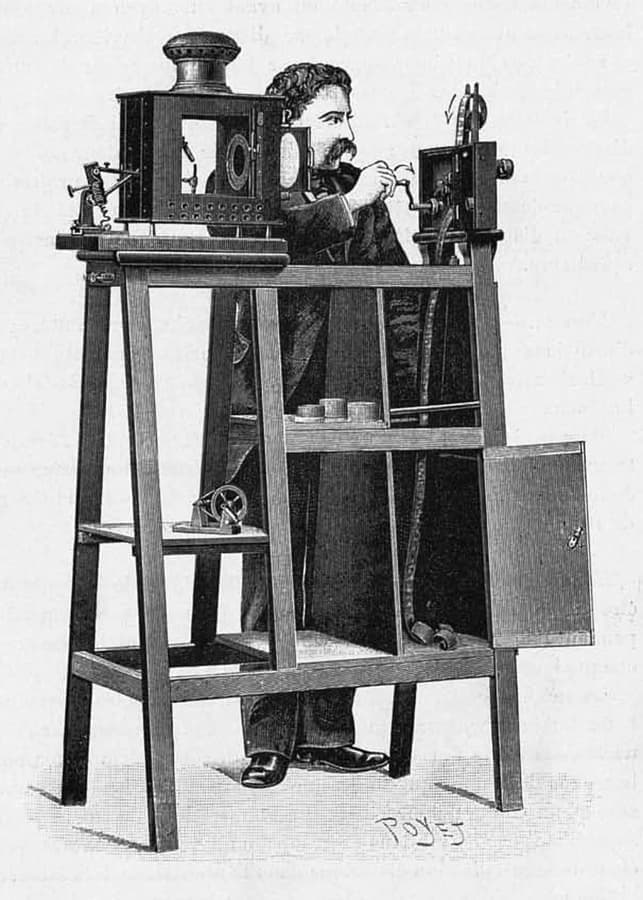

Sahhafbashi perhaps held glass plate shows (akin to present-day slide shows) before making his career in the cinema. These were performed with the lanterne magique, known as cheraq-e-sehri in Iran. In good shows of this kind, a succession of black and white—or, even better, color—glass plates depicting a story (as in today‘s comic strips) was projected on a screen. The lanterne magique was used in Mozaffar-ed-din Shah’s court and a couple of such color plates have been identified in the Album House of the Golestan Palace. Viewing was affected with one or another type of jahan-nama, including the stereoscope, in which a pair of almost identical pictures were used to achieve a three-dimensional view. It consisted of a small (or large) box equipped with two viewer lenses and a slot in which the glass plates bearing the image pairs were inserted. Examples of this type of jahan-nama, for example of Verascope brand, existed in Mozaffar-ed-din Shah’s court and in the hands of private individuals, because I have seen glass plates of this type, both processed and unprocessed, in the Album House of the Golestan Palace. Another type of jahan-nama, the Edison Kinetoscope, was completed in 1891. It was a large, hefty machine in front of which the viewer stood to watch a very short cinema-like film through a pair of lenses on its top. Other types of jahan-nama, namely Mutoscope, Kinora and Théoscope, also existed, in which cinema-like moving pictures could also be seen. The Théoscope, for example, was small and could readily sit on a foot.

As concerns lanterne magique shows, Nazem-ol-Eslam Kermani writes in his Tarikh-e Bidari-e Iranian:

The (lanter majik) cheragh-e sehri appeared in Tehran in the sixth year of the reign [of Mozaffar-ed-Din Shah]‖, which corresponds 10 April 1902–29 March 1903. What Nazem-ol-Eslam Kermani means by (lanter majik) cheragh-e-sehri is unclear. If he means the kind of shows current at the time, which consisted of projecting a succession of various scenes depicting a story (as in today’s comic strips), these had certainly―appeared‖, even if they had not yet achieved wide popularity, before this date. But, if he means the onset of private and semi-private film viewing with the lanterne magique and then the jahan-nama, then the date does not conflict with that of Sahhafbashi‘s film screenings. It is conceivable that, following the warm welcome given at the court to various types of lanterne magique, jahan-nama and Cinematograph, and perhaps after a second travel to the West in 1902, Sahhafbashi brought together a collection of such devices, together with X-ray equipment, electric fans and probably phonographs, etc., which he sold to the rich or used to hold shows. Therefore, Nazem-ol-Eslam Kermani‘s allusion to him—whom he says he knew well and with whom he was involved in underground political activity points directly to Sahhafbashi and his first public lanterne magique, jahan-nama and later Cinematograph shows. It was not rare at the time to refer to the Cinematograph as lanterne magique, and Khanbaba Motazedi, at the age of fifteen (1907), heard his father say that Russi-Khan had―brought a lanterne magique… which showed moving pictures‖ to Arbab Jamshid‘s residence.

The first reference to a theater (public cinema) is found in the absorbing memoirs of Nasser- ed-Din Shah‘s protégé. He wrote about the evening of Sunday 22 November 1903

I went to Sahhafbashi‘s shop. On Sundays he holds simifonograf shows for Europeans, and in the evening for the public. When I arrived there was no one; just me, a secretary of the Dutch embassy and a few of Taku‘s personnel. Taku was a European goods shop on Lalehzar Avenue. Apparently, on this occasion Malijak went to see a session for Europeans, because he adds: It was two and a half hours past sunset when I called for a landau. Accompanied by the supervisor [his teacher], I went to Sahhafbashi‘s shop to watch the Cinematograph.‖ Malijak. Taking the season into consideration, the cinema session began around eight o’clock PM. Malijak was interested by the cinema, because he again went to a session on the next evening. He wrote in his memoirs: “I called for a landau and we went to watch the simifonograf.”

Having watched for a while, we returned home.

This was probably no more than one or two days after Sahhafbashi had begun holding public film shows, because, had other films been shown earlier, Malijak would have certainly paid a visit or made an allusion to it in his memoirs. The study of Malijak‘s memoirs clearly shows that, fortunately for the history of Iranian cinema and photography, he truly was a full-fledged professional sloth. From morning to night, he paid visits to the court and the houses of different people, poked his nose into shops or wandered in the streets. Malijak‘s life and the style of his memoirs, particularly concerning everyday events, hunting, music, gambling… and social visits, are such that it is hardly conceivable for a public film show to have taken place without him noticing it.

Moreover, in those early years of the twentieth century, Malijak was also keenly interested in photography and music. He took piano lessons and was well aware of the existence of the Cinematograph. He had seen films at Mozaffar-ed-Din Shah‘s court at least as early as 1902, a year before the first public cinema was created. Although opposed with his political views, he was acquainted with Sahhafbashi and had paid him visits even before seeing films, mentioning the novelties he had seen in his memoirs. At first Malijak misjudged Sahhafbashi as an ignorant liar, but after seeing his X-ray equipment at work on the next day—Thursday 22 May 1902—he wrote extensively about it.

Unfortunately, as Malijak‘s memoirs begin on 20 March 1903 / 29, they hold no indication concerning the first four years of filmmaking in Iran. The first Iranian cinema, or tamasha-khaneh, was located in the yard behind his shop on Lalehzar Avenue.

Jamalzadeh writes about Sahhafbashi‘s estate: He had a building at the crossroads and avenue known as Comte, on the northern stretch of Lalehzar, on the left hand side, and he and his wife had transformed their home into a hospital… [and] they had [also] built a functional water cistern on the street side of their garden … The type of goods that Sahhafbashi had in his shop indicates that his customers came from among the aristocracy. Among the films shown there, Qahremanshahi mentions one in which a man ―forced more than one hundred [?] men into a small carriage and had a hen lay twenty eggs. Such comical or extravagant films were very popular at the time and lasted about ten minutes, as did most other films made in that period.

The history of the activity of Sahhafbashi‘s cinema must be limited from 21 November to 20 December 1903, because Malijak makes no other mention of its activity, Sahhafbashi having apparently traveled to America in the meanwhile. The month of Ramazan, which occurred in autumn in that year, was undoubtedly chosen on purpose, because spectators could easily use the long evenings to go to the theater after breaking their fast.

Financially, Sahhafbashi‘s venture seems to have been rather unsuccessful. For example, as we saw, only a few spectators were present at the first session attended by Malijak. And this was probably why Sahhafbashi moved his cinema to a new address on Cheragh-e Gaz (later Cheraq-e-Barq, and now Amir Kabir) Avenue after returning from America around 1905 and not later than 1908 in any case. If this change of address actually took place, it was not any more successful, and this time Sahhafbashi‘s theater closed its doors for good.

The only document on Sahhafbashi‘s travel to America is a bust photograph that shows him in European attire and which was reproduced by Jamal Omid together with the caption: “The picture] shows Mirza-Ebrahim-Khan Sahhafbashi (Mohajer) Tehrani [in] San Francisco.” Of course, the picture does not bear a date ―one must conclude that Sahhafbashi was away from Iran at least during 1904, and that the reopening of his cinema can therefore not have taken place before 1905.

The reopening of Sahhafbashi‘s theater is obscure and no contemporaneous written source concerning this event and the subsequent activity of this theater has yet come to light. As the present article does not intend to enter a long discussion on this reopening, we limit ourselves to a description of it as it was narrated by the late Abdollah Entezam, who attended Sahhafbashi‘s theater in his childhood, and another by Jamalzadeh, which may be related to

the same cinema. Neither Entezam nor Jamalzadeh gives any date, but Farrokh Ghaffari‘s inference from Entezam‘s description was that it was situated around 1905.

Entezam recounted his memories of Sahhafbashi‘s cinema to Farrokh Ghaffari in Bern, Switzerland, in October and November 1940. To his relation of this event to the author, Ghaffari added that Entezam had repeated these words in Tehran in 1949-1950), in the presence of the late Mohammad-Ali Jamalzadeh and himself, and that Jamalzadeh had confirmed to them. Jamalzadeh himself has been more cautious in his interview with Shahrokh Golestan, believing it ―very, very likely‖ that the cinema to which he had gone in his childhood was Sahhafbashi‘s, and adding that he could no more be sure about it See the full text of Jamalzadeh‘s account, reproduced a few lines below. He also spoke of Sahhafbashi‘s house on Lalehzar Avenue in a brief article he wrote on him in 1978 on the occasion of the reiterated notice of the sale of his chrome plating factory and theater equipment Jamalzadeh, but made no mention of the theater‘s reopening on Cheragh-e-Gaz Avenue or its connection with Sahhafbashi. Neither did Sahhafbashi‘s son, Jahangir Qahremanshahi, or Malijak, that professional sloth, ever mention any such reopening.

Despite these obscure points, doubting the reopening of Sahhafbashi‘s theater on Cheragh-e Gaz Avenue is not justifiable either, and for the present, in view of Entezam‘s solid testimony, the reopening in question should be considered as having taken place, and Jamalzadeh‘s memories of going to that cinema should be taken into consideration. Of course, it is much more probable that Jamalzadeh visited another, lesser, cinema on the same avenue. During the chaotic days of Mohammad-Ali Shah’s reign, others had begun setting up cinemas. They included Aqayoff, whose film shows were also held on Cheragh-e-Gaz Avenue but in the coffee-house of Zargarabad, and Russi-Khan, who had contrived a small cinema next to his photo shop.

Shahryar Adle (1944-2015) was a noted French-Iranian historian and art historian, who is recognized as one of the foremost scholars of Iranian studies. This article is an extract from a much larger study.