Helena P. Schrader has just published a very important book that we encourage you to read. It is The Holy Land in the Era of the Crusades: Kingdoms at the Crossroads of Civilizations, which counters common misconceptions and prevailing popular myths about the crusader states by demonstrating that religious tolerance rather than fanaticism, intellectual activity rather than warfare, and cultural exchange rather than bigotry characterized these unique societies. It is a fabulous and comprehensive history of the Latin East.

Helena Schrader holds a PhD in history from the University of Hamburg, which she earned with a ground-breaking biography of a leader of the German Resistance to Hitler. She served as an American diplomat in Europe and Africa, and since her retirement works as an independent scholar. Her areas of expertise are ancient Sparta, the Crusader States and the Second World War. She has also published six novels set in the Latin East. You can find out more at her website.

Please support Dr. Schrader’s valuable work by purchasing a copy of this unique book. To get you going, here is an excerpt.

Because of the ignorant or irresponsible misuse of the term “crusader” and “crusades” by politicians, journalists and Islamist terrorists, long-discredited theories from the last century about the crusades have been perpetuated with thoughtless references and careless comparisons. This shallow and sensationalist – not to mention intellectually lazy – commentary drowns out the voices of serious scholars. As a result, most of the public today believes that the crusades and the crusader states were characterised by bigotry, racism and brutality aimed at the oppression and destruction of the native peoples of the Near East.

Yet, the picture of the crusader states that scholars have meticulously pieced together based on contemporary chronicles, data mining and archaeology does not corroborate these popular assumptions. Instead, the historical record provides concrete evidence of Frankish tolerance, adaptability, peaceful co-existence and cooperation with the various peoples inhabiting the Middle East. For example, from the moment they arrived in Antioch, the crusaders preserved, cherished and expanded the Arab libraries they discovered. Rather than destroying mosques and synagogues, the crusaders either repurposed them or allowed them to continue to operate, preserving these architectural monuments for posterity. Furthermore, the crusaders allowed Jews, Samaritans and Muslims to build new houses of worship. They allowed these religious groups to live according to their laws and publicly celebrate their religious festivals without interference.

Likewise, from the First Crusade onwards, the Franks recognised and respected the Orthodox clergy, at times taking Orthodox priests for their confessors and consistently sponsoring the re-establishment and restoration of Orthodox churches and monasteries. As a result, Greek monasteries flourished and expanded, particularly around Jerusalem, in Antioch and Sinai.

The hospitals of one of the crusading orders, the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem, employed doctors of any religion. In the luxurious wards, patients of all religions were treated equally as “lords” by members of an order that viewed themselves as “serfs” of the poor.

The courts sought to ensure that anyone accused of a crime was judged by his peers following local custom rather than an alien legal code. Civil and criminal conflicts between members of different ethnic and religious groups were adjudicated in accordance with the law of the defendant.

Absent from the popular image of crusaders and the crusader states are the more than one hundred truces and the many alliances across religious borders. Likewise, the native Christians who worked as scribes, customs officials, merchants and manufacturers, both forming the administrative backbone of and contributing materially to the economic prosperity of the Holy Land have been erased from popular history by the simplistic popular picture of the crusader states. Invisible too are the Arabic and Syriac-speaking native Christian infantry and archers that made up the bulk of the Frankish armies, even though these fighting men saved the crusader states from destruction on multiple occasions.

The popular picture of the crusader states does not include the icon workshops, mass book production, or a society that rewarded knowledge of the law as assiduously as skill with the sword. Forgotten are the Muslims who sought refuge in the Kingdom of Jerusalem during the Mongol invasion of Syria and the Jews who immigrated to the Kingdom of Jerusalem because it was an oasis of tolerance in an anti-Semitic world. The historical reality of Templars hosting the Ayyubid princes in their Acre headquarters in 1244 and Frankish noblemen translating Arab poetry into French is obscured by Hollywood depictions of Templars shouting for Muslim and Jewish blood and Frankish noblemen slaughtering unarmed Muslims.

Yet, it is not only the need to correct common misconceptions that make the study of the crusader states rewarding. These kingdoms, sitting on the crossroads of civilizations, were established by newcomers from the West who were compelled to adapt rapidly to their new environment or face extinction. Not only did they adapt, but they evolved into a unique hybrid society that mixed European culture with Near Eastern traditions. This was not a matter of imitating—much less “stealing”—technology, art or ideas from more sophisticated neighbours. It was a matter of developing new and innovative products, forms and concepts. In doing so, the Franks of Outremer made significant contributions to the evolution of European society, stimulating advancement across a range of fields.

The most obvious innovations came in the field of warfare. From the adoption of surcoats to the construction of concentric castles, the confrontation between the armies of the Middle East and Western Europe led to significant military advances. The Franks pioneered Western use of mounted archers, evolved the fighting box (combined arms warfare), and in the military orders, rediscovered the value of professional and disciplined regular forces. They perfected the massed charge of heavy cavalry yet also effectively exploited light cavalry in reconnaissance and hit-and-run raids. Finally, they deployed archers behind shield walls to good effect, while Frankish crossbows represented cutting-edge technology. In his study of crusader warfare, Steve Tibble concludes that “warfare in the east was a crucible of innovation for European warfare.”

The architecture of the Franks was unique and not only regarding castles. Frankish domestic architecture combined such Western features as outward-oriented multistorey structures, high ceilings, large windows, loges and balconies with Arab and Byzantine artisanry, such as inlaid marble, glazed tiles, running fountains and intricate decoration. The result was gracious and sunlit structures that used local products such as glass windows, glazed tiles and polychrome marble. Frankish houses included fireplaces with hoods that reduced smoke accumulation (a Western feature) and sophisticated plumbing systems of cistern-fed ceramic pipes feeding into centrally-planned sewage systems (an Eastern feature).

As noted earlier, hospitals as institutions for healing the sick and injured evolved in the Holy Land in the crusader era, based on Byzantine and Arab precedents. Along with hospitals came advances in medicine and progress towards the professionalization of medical practitioners and the protection of patients from malpractice. The Frankish states provided a meeting place for physicians from various cultures, and Antioch became a centre for the study and development of medical theory.

International banking was another field significantly advanced by the Frankish presence in the Levant. The need for cash transfers over enormous distances fostered the evolution of letters of credit, cheques, currency exchange and other financial services previously unknown, at least not on such a scale.

Last but not least, the Franks contributed to constitutional law. Nowhere else in the medieval world was interest in and discussion of the concept of good governance, the rule-of-law and the monarch’s role carried to such heights of sophistication or conducted on as wide a scale as in the Kingdom of Jerusalem in the mid-thirteenth century. In no other kingdom did so many noblemen of a single era study and write about the law, let alone serve as advocates in the courts. The Kingdom of Jerusalem was also exceptional for the number of men of lower social standing who gained prominence through legal expertise. The inclusion of the commons in governing assemblies was equally innovative and progressive, albeit limited. Yet most important was the advocacy and defence of key constitutional concepts such as the monarchs’ subordination to the constitution and the right to due process. In defending these principles against the authoritarianism of Frederick II, the rebels of Outremer undoubtedly influenced the English parliamentary reformer, Simon de Montfort. They deserve credit for their steadfast opposition to tyranny.

The Frankish states of the Levant were not paradise. Even if not perpetually on the brink of collapse, they were vulnerable. They were subject to frequent small-scale attacks, periodic invasions and were ultimately destroyed by warfare. In the thirteenth century, they also suffered from absentee monarchs, political intrigue, and factional infighting. Yet, they were neither fragile constructs doomed to failure nor genocidal, apartheid regimes established by barbarians to oppress enlightened natives.

The evidence is overwhelming—preserved in stone and meticulously documented by Arab, Greek, Syrian and Jewish sources no less than in the Latin and French chronicles: The crusader states in the Levant were the home to a rare flourishing of international trade, intellectual and technological exchange, innovation, hybrid art forms and unique architecture, advances in health care and evolution of the constitutional principles of the rule-of-law. They brought forth a vivid, multicultural society in which tolerance outweighed bigotry. As such, the crusader states’ contribution to the evolution of European culture deserves more attention and appreciation as we struggle to integrate diverse cultures in our own time.

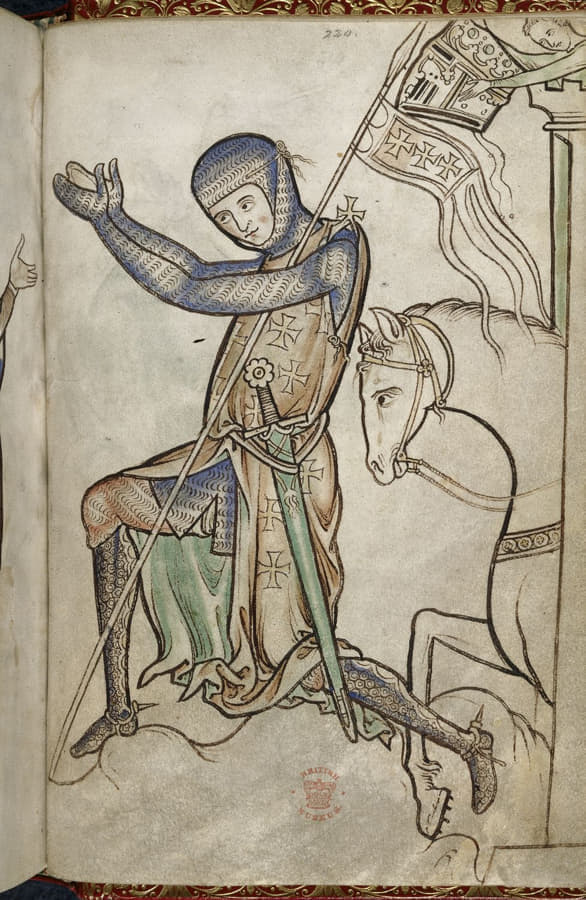

Featured: Knight, Westminster Psalter (BL Royal MS 2 A xxii f. 220); 13th century.