There is an elective affinity—a relationship of reciprocal attraction and mutual reinforcement—between (a) John Locke’s argument that a child’s mind initially resembles an “empty cabinet” or a “white paper void of all characters,” which can be shaped by controlling the education impressed upon the child’s mind, and (b) the origins of a literature specifically written for children in the 1700s in England. John Locke’s pedagogical book, Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1692), with its thesis that “children’s minds” could be shaped “from without” by “those who have children or the charge of their education,” became “the moving spirit of the eighteenth century.” Samuel Pickering documents in his book, John Locke and Children’s Books in Eighteenth Century England (1981), the influence of Locke on the “form, theme, content, and diction” of early children’s literature. Pickering does not, however, draw connections between Locke’s blank slate thesis and the development of children’s literature. Below I will outline the history of children’s literature as a singularly Western phenomenon that calls for an appreciation of Locke’s blank slate thesis. The focus will be on English and American books, where the influence of Lockean philosophy was greatest, though we should keep in mind that other European nations were originating children’s literature. Folk tales, superstitions, songs, legends—that taught and entertained children—have been common throughout the world. Before the early 1700s, however, there were no books written specifically for children.

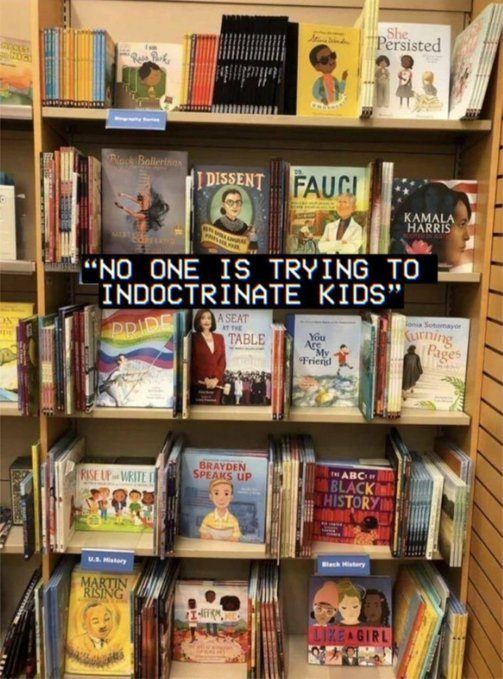

Children’s literature undergoes momentous changes in content and theme in the course of time as the West finds itself in a state of continuous modernization and cultural change, driven by new concepts of childhood: from purely instructional stories with practical advice in the 1600s, along with evangelical stories to keep the innate moral sinfulness of children contained, through to stories after 1700 offering both knowledge and recreation that encouraged children to be virtuous and kind to animals. From books in the early 1800s teaching middle-class children the values of thrift, hard work, and family uprightness, through to sentimental stories about the harsh lives of poor Victorian children, and stories encouraging the predilection of children for fantasy and imagination after the 1850s. From stories about heroes and the virtues of loyalty, pluck, and resourcefulness at the time of British imperial greatness, coupled with the rise of girl’s stories to prepare them to be wives and mothers during late Victorian times, through to stories about the unchanging trials of adolescent sexuality after WWII, combined with science fiction and comic books, to a new agenda of political correctness in matters of sex and race from the 1990s onwards, which brings about a degradation in the quality of children’s literature as it becomes a weapon aimed at indoctrinating children into accepting “diversity, equity, and inclusion.”

The Beginnings of Blank-Slate Children

Among conservatives and evolutionary psychologists who believe that humans are born with innate biological drives that explain their behaviors, motivations, and intellectual aptitudes, Locke’s blank slate argument is today dismissed as a major error driving the Left’s ideology that humans are malleable creatures who can be easily “reimagined” or “reconstructed” anyway one chooses. Everyone knows about the nature versus nurture debate. But what many on the dissident right have not paid due attention to, preoccupied as they have been with the science of genetics, is that the blank slate proponents, for all the “refutations” they have faced in the writings of such prominent scholars as E.O Wilson and Steven Pinker, have taken complete command of children’s books across all the schools, libraries, and publishing houses of the Western world.

They managed to do so because the West has been demolishing its “innate ideas” for centuries now, its kinship-based institutions and norms, its customs, folkways, and traditional religious beliefs. The in-group psychology dominating all traditional societies was fundamentally altered in Europe into increasingly individualistic habits of thinking and behaving as Europeans started demolishing their kinship institutions from the Middle Ages onwards, by prohibiting cousin and polygynous marriages and promoting monogamous nuclear families. This released Europeans from their kin-based obligations and encouraged them to choose their spouses, social friends and associates, which opened the door to the creation of voluntary (civic) associations, chartered towns, guilds, universities, monasteries, and representative institutions based on contractual agreements. Kinship was no longer determining the “innate” identities and norms of Europeans, their ascribed status and obligations, their sense of right and wrong, their normative relationships between family members, what values should be transmitted to children, what is sacred and what is profane.

European institutions and associations were now based on civic norms chosen by anonymous individuals on their own initiative. However, for a long time, through the medieval era, Christianity continued to act as a major collective source guiding Europeans in their families, education, and overall social life. But as modern Europeans began to talk about the “natural rights” of individuals to choose their own values and happiness within an increasingly commercialized society, the traditional values of the Church started losing their influence, particularly after the Enlightenment. This led to the expansion of the blank slate interiors of Europeans, and the rise of ideologies contesting over which values should command the lives of individuals. The West is indeed unique among civilizations in the origination of ideologies proposing a complete remaking of society: liberalism, socialism, communism, anarchism, feminism, fascism. Non-Western societies are innately based on their millennial traditions. The West became ideological during the French Revolution as a new intelligentsia consciously set out to remake society anew. Even conservatives became ideologues when they realized they could not restore the old monarchical order and the old aristocratic class, but had to accept the liberal principle of equality of civic rights and modern industrial development—if they were to preserve in a new form some traditional values. Western liberalism (which gradually came to include many sub-isms within itself, including modern conservatism) eventually defeated the two major contenders for power, fascism and communism, proclaiming the “end of history” in the 1990s.

In the England that Locke was born, a relatively new liberal society where parliamentary rule had displaced monarchical authority, and where the nation would increasingly come to be seen as a contractually-based covenant among anonymous individuals with natural rights, rather than based on kinship in-group loyalties, it made sense to reject innate ideas. The classical liberal disposition to accept nothing as true unless it was validated by one’s “impartial” rational judgment, amplified the intellectual creativity of the West. Painters, musicians, sculptors, architects, and novelists were encouraged to rely on their individual aesthetic judgments in the pursuit of the highest forms of beauty and literary expressions.

For all their individualism, however, modern Europeans, until recent decades, remained attached to their national heritage, creating nations based on a collective sense of history, memories, and ethnic identity. Christian traditional values continued to play a big role in the parenting and education of children through to the twentieth century. The liberal ideas of Locke were not calling for a world without any traditions and common heritage; his liberalism was sensibly aimed at encouraging the initiative, curiosity, and knowledge of children, in a world where formal schools for children were just beginning and most instruction was religiously oriented and paternalistic. Locke argued with reason that education should not be despotic and coercive but should account for the individual characteristics of children, encouraging their interest in knowledge, while disciplining their habits without indulging their subjective whims.

The Impact of Locke in the 1700s

There were books for children before Locke: The Petit Schole (1587) taught the rudiments of English spelling; A Method, or Comfortable Beginning for all Unlearned (1570) was about how to teach reading; and, before these two, there was Caxton’s Book of Curtesye (1477) about piety, neatness, honoring one’s parents. Children enjoyed some adult books, such as Plutarch’s Lives of heroic Greeks and Romans, the adventure, the great deeds, and the anecdotes. Richard Mulcaster’s Positions Concerning the Training Up of Children (1581) actually encouraged laughter among children and the importance of exercise and games. Locke later elaborated upon this view, urging that education should involve “Play and Recreation” as a means of getting “continued Attention” from children, engaging the “liking of Children” for learning, which is “one of the hardest Tasks.” Children should be free to choose how they play, so they discover their individual tempers, inclinations and aptitudes.

But while England awaited Locke’s “monumental educational influence” in the early 1700s, it was the “Good Godly Books” by Puritans that constituted the greater part of books for or about children. There was a “flood of Puritan books” in the 1600s. Puritans advocated literacy among the young for two interconnected reasons: they believed that individuals should have direct access to the Bible and that encouraging children to read didactic literature was an excellent way to rescue them from their sinful impulses. “Play and idleness” gave children time for devilish temptations without fomenting an upright character. (The historian Percy Muir makes the revealing observation that “the Cambridge Bibliography of English Literature lists no children’s books of a recreational kind before 1671”). A good example of Puritanism in books was James Janeway’s A Token for Children: being an Exact Account of the Conversion, Holy and Exemplary Lives, and Joyful Deaths of several young Children, published in 1671. In this book, abstinence from all forms of playfulness was insisted upon, with constant reminders to the parents of the inherent tendency of their children to sin, and the need to raise children guarded against the temptations of Satan by reading the Scripture. The same, however, cannot be said about John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678). While this book was not intentionally written for children, it was widely read in the nursery and annexed by children as an adventure story about giants and fabulous monsters, sword contests, and a hero overcoming ill fortune. It has been said that Bunyan provided amusement, if “unintentionally”, and that he preferred to persuade children into righteousness instead of frightening them.

It was in the early 1700s that books expressly written for children came onto the market, guided by the Lockean conception that children were not born with original sin but resembled an “empty cabinet” that could be shaped according to their education. This Lockean idea was reinforced by a “new sensibility” attributed to Rousseau’s educational novel Émile, written in 1762, which argued that the natural state of being of children should be valued in itself, rather than viewed as an inferior state requiring the immediate imposition of adult ways. This emphasis on the “natural” ways of seeing, thinking, and feeling of children would eventually encourage the writing of books aimed at nurturing the unique imagination of children.

With the gradual modernization of Britain, there was a growing focus on the educational maturation of children. Up until about 1750, roughly speaking, almost one-third of young people died before 15 years of age. Coping with such regular deaths in their households, combined with the need to have young adults help with farming and craftsmanship, parents barely had time to think about their children’s education. But with improvements in agriculture, the rate of infant mortality started to decline very slowly but steadily through the 1700s, making parents more optimistic about the prospects of their children surviving into adulthood and the importance, accordingly, of an education in an emerging urban Britain where a vocational profession was important. Sunday schools that taught reading and writing and some arithmetic were growing in great numbers during the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In 1800 there were 2,000 such schools, with about 10 percent of children between the ages of five and eighteen enrolled. By 1818 some 450,000 children were being educated in Sunday schools.

Apart from books aimed at preparing middle-class children for social accomplishment, such as Circle of the Sciences series (1745), an encyclopedia published by John Newbery about grammar, arithmetic, geography, we see a growing emphasis on books that taught moral and religious principles in a more light-hearted, liberal manner, acknowledging playfulness in children’s learning. A popular book was Sarah Fielding’s The Governess; or, The Little Female Academy (1749), about a girls’ village school with a teacher of virtuous character who tells her students that “the true use of books is to make you wiser and better.” A book that inspired a whole genre was The History of Little Goody Two-Shoes (1765), by an anonymous author, about a “do-gooder,” a poor orphan girl named Margery Meanwell, who goes through life with only one shoe until a rich man gives her a pair, and she tells everyone she has “two shoes,” and then becomes a teacher and marries a rich widower, with the story showing that virtue is rewarded.

In Some Thoughts Concerning Education, Locke encouraged parents to teach their children kindness to animals, warning that “the Custom of Tormenting and Killing of Beasts, will, by Degrees, harden their Minds even towards Men.” This outlook occasioned a debate about the contrasting natures of humans and animals, whether animals had souls, how should the Christian doctrine of universal charity be applied to animals, with the consensus being that while animals should not be elevated above humans, they should be put to death only when “necessary either for the food or convenience of man” without cruelty. Thomas Boreman’s Gigantick Histories (1740), which would eventually comprise a series of ten separate volumes, was endearing to children in its depiction of animals, with stories about lions, tigers, and leopards, all of which Boreman described and illustrated with woodcuts. A book viewed as “the most representative of children’s books”, in which animals began to be sentimentalized, is Sarah Trimmer’s Fabulous Histories (1786). The book emphasizes the virtue of social hierarchy, according to which parents are above children in their authority, humans above animals in terms of dominion and compassion, while conveying the message that kindness to animals during childhood can lead to universal benevolence adulthood.

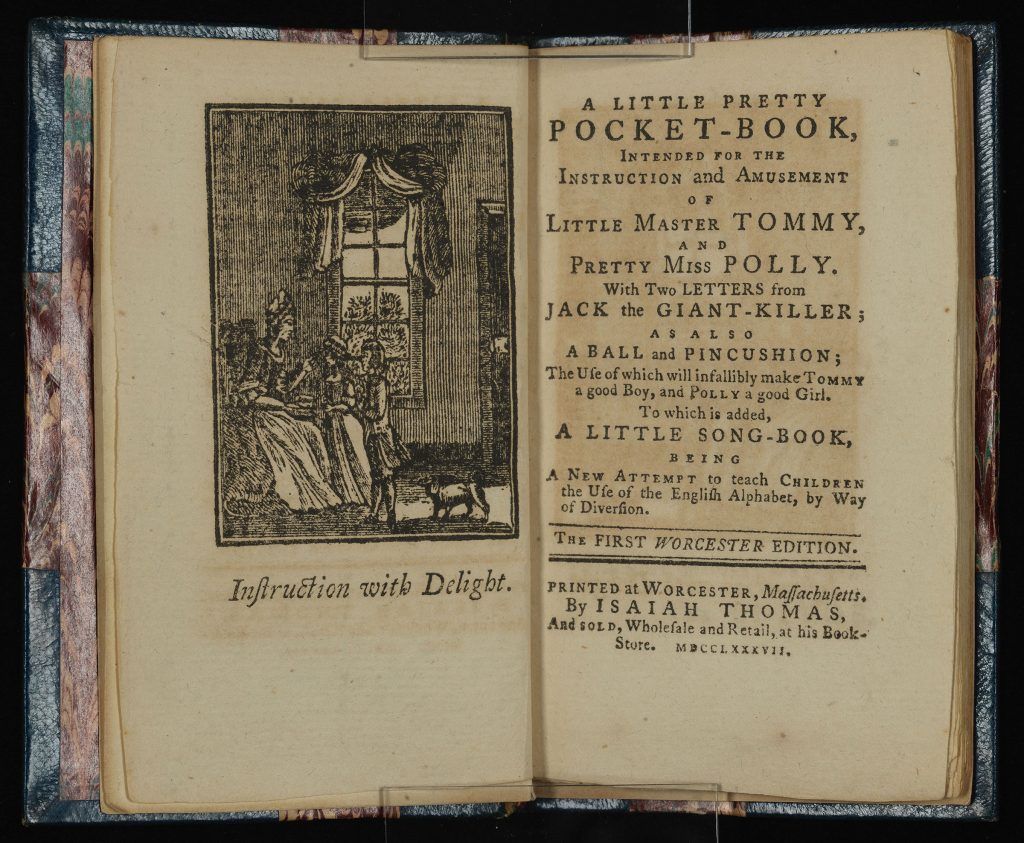

It would take all our space to describe the onrush of children’s books during this period. One of the first and most prolific publishers of books for children and juveniles was John Newbury, who consciously followed Locke in his decision to link “a Knowledge of the Letters” to “Play and Recreation.” The first book he published, in 1744, was A Little Pretty Pocket-Book, intended for the Amusement of Little Master Tommy and Pretty Miss Polly with Two Letters from Jack the Giant Killer, identified by some as “the first children’s book in history,” consisting of simple rhymes for each of the letters of the alphabet. Newbury “paid great attention to every detail” in the preparation of children’s books, “the titles, heroes, reputed authors, price, size, binding and pictures were scrupulously attended to.”

It is not an exaggeration to say that Europeans invented childhood in the late 1700s as they started showing a keen interest in the individuality and personality of children. Prior to this time, children were depicted as small adults in their clothing, postures, and facial expressions. The appearance of boys at school was that of a “small-size adult;” it was only at the end of the 1700s that “special dress for children began to appear.” Children were expected to think and behave as mature people at about the same age as our children today embark on their primary education. In late 18th-century Britain one sees a new artistic interest (headed by the British) in young children, aimed at bringing out the distinctiveness of childhood. Children had their own identity already as infants. The paintings of Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792) are very important in this respect. Art historian Ann Higonnet described this new artistic phenomenon as the invention of the innocence of childhood. It was this innocence that defined the distinctiveness of children, as conveyed by one of Reynolds’s child portraits entitled “The Age of Innocence.” An innocent child’s body was “defined by its difference from adult bodies.” The stages of maturation of children came to be clearly defined sometime between 1780 and 1820: between the infant and the child, the child and the adolescent, with authors delineating the specific educational needs for these stages.

Ellenor Fenn, author of numerous books, stated that “if you expect children to read with spirit and propriety they must be supplied with lessons suited to their taste, that is, prattle, like their own.” Fenn is now acknowledged “as an early advocate of child-centered teaching strategies.” A follower of Locke, she opined that “if the mind be a rasa tabula—you to whom it is entrusted should be cautious what is written upon it.” Her most popular book, Cobwebs to Catch Flies (1783), a reading primer, which consciously differentiated between reading age groups, with parts of the book aimed for children from three to five years, and later parts of the book aimed for those from five and eight. The book met children at their own age, experiences and interests, in how it addressed toys, pets, games, visits to the fair and other subjects.

Chapbooks, Fairy Tales, Robinson Crusoe

The first books written for the delight of children in rural poor homes were “chapbooks,” that is, half penny sheets covering a range of subjects from alphabet books and religious stories and prayers, to legends of ordinary folk, short biographies, heroic tales, crime news, songs and jests, and nursery rhymes, such as “Who Killed Cock Robin” and “Little Tommy Tucker,” miraculous or ghost stories, prophecies and fortune-telling, battle or adventure. Fables have always been the oral possession of the illiterate. The development of these fables and fairy tales into books began in the early 1700s. The Histories, or Tales of Past Times Told by Mother Goose (1729) was a translation of a book originally published in 1697 in the French, a collection of children’s tales including “Blue Beard,” “Sleeping Beauty,” “Cinderella,” “Puss in Boots,” and “Little Red Riding Hood.” These stories were original adaptations in prose of preexisting medieval folk tales.

It is worth mentioning that, while folk tales are common to all cultures, being anonymous stories that communities passed through the generations by word of mouth, Europeans started a literary scholarship of folklore, collecting and writing down in published form these tales during the seventeenth century. The Grimm brothers, Jacob (1785-1863) and Wilhelm (1786-1859), with their background in philology, meticulously recorded the tales exactly as the people told them, writing down every variation, publishing 86 fairy tales in 1812, and 217 unique tales by 1857. Hans Christian Andersen (1805–1875), a Danish author, not only collected tales but wrote dozens of original fairy tales—The Tinder-Box, Thumbelina, The Little Match Girl—leading some to argue that he invented the literary fairy tale of pure fantasy about magical characters, such as wizards, elves, trolls, gnomes, goblins. By 1800, book publishing had increased substantially with one catalogue listing 213 “amusing and instructive books for young minds.” Many were adaptations for children of well-known tales, such as Mother Bunch’s Fairy Tales (1773), or nursery rhymes, Mother Goose Melodies, lullabies, and stories about animals, such as The Dog of Knowledge (1801), or The Adventures of a Bullfinch (1809). The most popular children’s book was The Comic Adventures of Old Mother Hubbard and her Dog (1805), by Sarah Catherine Martin (1768-1826), selling over 10,000 copies, about a male dog who is mischievous and a female cat who helps with various chores around the house.

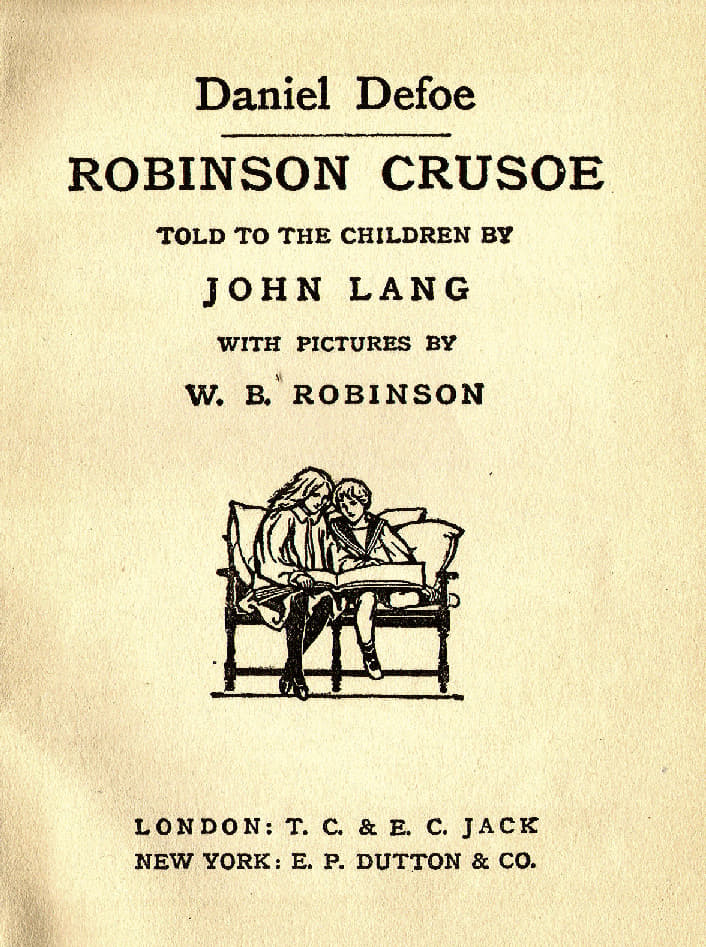

Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) was intended for an adult readership but soon educationists pointed to the pedagogical merit of this story, and its compatibility with Lockean pedagogical theory, providing “instruction with delight.” The New Robinson Crusoe: An Instructive and Entertaining History, for the Use of Children of Both Sexes by Joachim Heinrich Campe, published in 1788, was the earliest Crusoe for children, with countless children’s versions appearing over the years. Rousseau argued that Crusoe should be a primary text to raise children “above vulgar prejudices” and encourage them to form their own judgments by imagining themselves as “solitary adventurers” in a natural state, building their own life in circumstances of real utility. Today, Robinson Crusoe, is condemned as a story that “upholds a racist ideology of white supremacy.” Crusoe was certainly the embodiment of European individualism, the Lockean ideal of recreating society and oneself out of a blank slate, the quest to become one’s own. According to Ian Watts, Robinson Crusoe was the first true novel in history in not taking its plot from mythology, or history, or from previous literary genres; the first story thoroughly preoccupied with the primacy of individual experience rather than general human types, giving attention to minute details of ordinary life, with a highly introspective character where almost every action is a subject of self-examination, a monologue, centered around Crusoe’s feelings, beliefs, fears, judgments—in isolation, the self as master.

Victorian Morals, Imagination, and Sentimentalism

In the first decades of Victorian England, 1820-1850, children’s books reflected the ideology of the new middle classes: “modesty and moderation, prudence and self-help, respectability and thrift”—a combination of Puritan morality and self-reliance. The father was still the head and the role of the mother was to attend to the moral well-being of the family, which on average consisted of 4 or 5 children brought up on strict gender-based roles, with the sons expected to prepare for success in the public sphere and the daughters to become ladylike in preparation for a married life, though women did play a public role, becoming prominent writers of children’s books.

Barbara Hofland’s writing drew on the hardships of her own life as a widow and during her second marriage to an artist without money; in The Blind Farmer and his Children (1816), and Elizabeth and her Three Beggary Boys (1833), she depicted families struggling under hard circumstances (death of parents, bankruptcy) yet prevailing due to their moral integrity and Christian ways. The women in her tales showed strength not by condemning Victorianism (she was a firm advocate of marriage) but by showing strength as wives and widows, even if it meant having to set up their own businesses in the face of the father’s bankruptcy. Victorian “rigidity” however saw more than didactic moral tales. Harriet Mozley’s The Fairy Bower (1841) and Family Adventures (1852) portrayed children as they are rather than as mere vehicles for adult expectations, enjoying jokes, skating, and arguing about the propriety of their own behaviors. Peter Parley’s Magazine, an English children’s magazine published monthly from 1839 to 1863, contained articles about history, travel, animals, and moral tales about school boys, wicked uncles and other subjects, colorfully illustrated, aiming to instruct and please children.

There were adventure stories about overcoming ordeals, such as The Settlers at Home, by Harriet Martineau, in which a land is flooded, with mills and barns floating away, farm animals drowning, and everyone in great peril…four children are deprived of their mother and father…the two-year-old baby dies, and they have various struggles for survival…until they are rescued. Frederick Marryat’s The Settlers in Canada (1844) was about the adventures of an immigrant English family threatened by “Red Indians” and wild animals. His The Children of the New Forest (1847) was about 4 orphaned children during the Civil War, taught by a forester how to survive by hunting and farming. This age of realism and railways was also an age of the “romantic rediscovery of the imagination.” In addition to numerous new versions of Grimm’s folktales, and translations of Andersen’s tales into English, original works of fantasy were written, most notably Phantasmion (1837) by Sara Coleridge, a story of a prince who embarks on a journey, taunted and manipulated by mysterious spirits, and finally triumphs over the forces of darkness after multiple trials.

From its Puritan beginnings in the 1700s to 1870, American children’s literature experienced significant cultural shifts reflecting changed perceptions of childhood. Between 1650s-1750s children’s books were for instruction and a Puritan upbringing—to fight ignorance, the “mother of heresy,” and to restrain children’s “inborn depravity.” A widely read book was The New England Primer, published in the 1680s, illustrated with woodcuts, in verse for easier memorization of its teachings—with its famous opening “in Adam’s fall, we sinned all.” Thumb bibles decorated with pictures were common; one popular book was The Duty of Parents to Pray for their Children (1703) by Increase Mather. The best known was John Bunyan’s English classic, The Pilgrim’s Progress, of which 50 editions were published in America by 1830. Children enjoyed its strong dramatic narrative of Christian, an everyman character, journeying from the “City of Destruction” to the “Celestial City” seeking deliverance from the burden of his sins. Many new titles came out after 1750s: one publisher in Massachusetts published more than 100 titles between 1775 and 1800.

While the 1800s saw a gradual shift “away from the spiritual intensity” of Puritanism “toward a more generalized moralism,” the typical children’s story before 1850 did not encourage fantasy or imagination: the focus was on moral character, not entertainment. The Story of Jack Halyard (1824) was intended “to give an account of one family of superior excellence, as a model to others.” After 1850, a new kind of writing emerged, giving “childhood a value in and by itself,” an idealized perception of childhood expressed in sentimental stories about children “which was often put at the service of some social purpose.” The matter-of-fact deathbed scenes of earlier literature gave way to vivid, melodramatic narratives, such as The Angel Mother (1854), about a mother’s death and the prolonged mourning of her children. Stories of poor children, “filthy, ragged, barefoot even in winter,” such as Alice Haven’s Nothing Venture, Nothing Have (1854) about a tenement “crowded with families as poor, and as squalid as want could make them,” were common. With the rise of cities, there was a focus on secular subjects and characters: shopkeepers, newsboys, Italian boys singing on the streets for pennies. Series books in magazines were launched, adventure tales for boys. Horatio Alger was best known for his “rags-to-riches” stories of boys rewarded for hard work, acts of bravery or kindness. The most beloved book was Little Women by Louisa Alcott, about the fortunes of four sisters in their passage to young womanhood, which inspired numerous films.

Golden Age in England and America

The history of children’s literature points to the English as the most prominent, original writers. The period 1850-1890 has been identified as a “golden age,” with writers drawing on translations of the rich repertoire of Hans Andersen’s fairy tales and fables—at the same time as Europeans came to view childhood as a crucial phase in personal development, characterized by freedom from accepted conventions, vitality of imagination, and the child’s instinctive connection to the natural world, reflecting the earliest phases of the human psyche, and thus a window to the archetypes of the unconscious. Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventure in Wonderland (1865) is judged as possibly the most brilliant and original children’s book. By removing the controlling voice of the adult’s narrator and having children speak for themselves, Alice’s was the first to allow the child’s mind to occupy the centre, as the adult re-enters into their sense of puzzlement. Charles Kingsley’s Glaucus; or, The Wonders of the Shore (1855) was inspired by nature walks with children, to bring out “the miraculous and divine element underlying all physical nature.”

There was a sentimental belief in the child’s innate virtues, away from the earlier emphasis on original sin, characterized by a keen concern for the suffering of poor, homeless, vagrant children, the so-called “street arabs.” George Sergent’s book, Roland Leigh: The Story of a City Arab (1857), was about a small boy in the London underground abandoned even by the church. For Hesba Stretton children were society’s victims; her stories of children “starved of food and affection” were widely imitated; she popularized “baby talk.” Juliana Horatia Ewing, from a family of ten children, with a strong faith, is known for her efforts to bring out children’s feelings, closeness to one another and to their animals. Her stories, such as Mrs. Overtheway’s Remembrances (1869), are celebrated as the “first outstanding child-novels.”

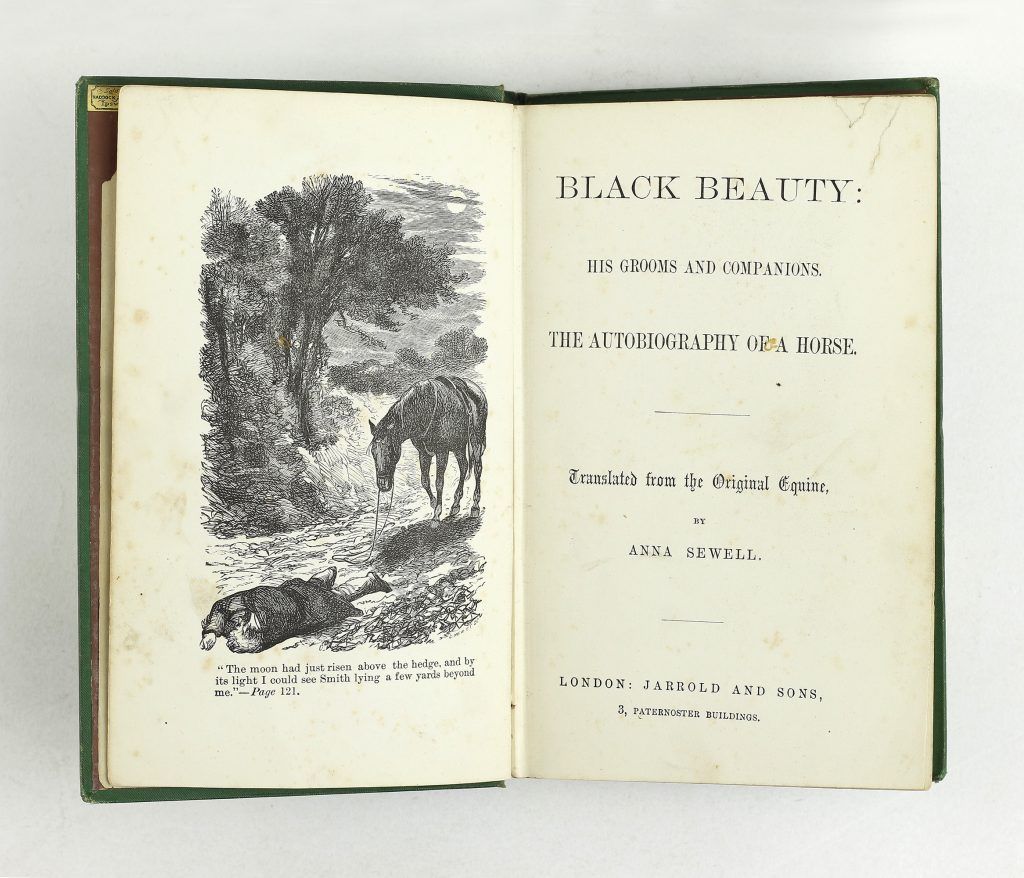

The year 1877 saw the publication of Black Beauty, one of the best-selling children’s books of all time, written by Anna Sewell while seriously ill—about a horse dragged down by harsh masters and vain mistresses. It is an animal autobiography, in which the horse, Black Beauty, is given some human traits, such as thinking and talking, although only the readers can hear Black Beauty talking; none of the human characters in the text hear the horses, who communicate with human characters using gestures and actions. Like earlier books about animals, Black Beauty is anthropomorphic, with the horse playing the role of narrator, with the readers understanding the world through the horse’s own perspective. This story is now considered one of the first animal rights books in its exploration of the suffering faced by horses at a time before the invention of automobiles, when society depended on horses for transportation. Europeans have had a strong connection to horses since Indo-European peoples domesticated them in the Pontic Steppes during the fourth millennium, and then invented the techniques of horse riding, and chariots.

As England expanded across the world, adventure stories took off; one of the most widely known is Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883), a story with everything boys love: treasure, pirates, strange noises, seafaring—along with unpredictable characters, a fallible hero and a “formidable and smooth” villain. The novels of the French writer Jules Verne, “father of science fiction,” were very popular among English boys, including Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864), Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas (1870), and Around the World in Eighty Days (1872), taking his readers across continents, under the oceans, through the earth, and into space. George Alfred Henry’s stories, The Dragon & The Raven (1886), For The Temple (1888), Under Drake’s Flag (1883) and In Freedom’s Cause (1885), were also enjoyed, with their blending of the extraordinary with the probable, eulogizing honesty and loyalty, pluck and resilience—with his belief that the British were unequalled in these virtues. The late nineteenth century saw a sudden attraction for boarding school stories, attuned to the different interests and experiences of boys and girls. Talbot Baines Reed was the most popular writer of boys’ fiction about rivalry over games, school boy humor, and a muscular type of Christianity—The Fifth Form at St. Dominic sold 750,000 copies in 1907. The most prolific author of girl school stories was L.T. Meade; in addition to her books for adults, Meade wrote about 150 titles for “young readers;” A World of Girls: The Story of a School (1886) was about disruptive emotions, friendship, loyalty, and jealousy, along with Victorian attitudes of traditional roles of wives and mothers.

The enfeebled liberal West you see today publishing grooming stories about transsexuals to primary school children was once continuously creative. It was so because its blank slate individualism was still sustained by traditions, solid monogamous nuclear families, the continuing presence of Christian values, patriarchal authority, and a sense of national heritage. During the late and early twentieth centuries there is a marked preoccupation with the inner world of children, not merely with childhood as distinctive phase, but in rediscovering in the interior world of children the loss of human wholeness, the dismemberment of industrialized and wealthy humans from nature, overcoming anomie and rootlessness. The Secret Garden (1911) by F.H. Burnett has been interpreted many ways. It is through a secret garden drawn from fairy tales (outside modernity) that the orphaned Mary finds consolation and reconciliation after living as a selfish and disagreeable 10-year-old girl spoiled by her servants in colonial India and neglected by wealthy British parents. Mary finds an abandoned garden where she takes her disabled 10 year-old cousin Colin to see the garden, where he manages to stand up; they plant seeds together to rejuvenate the garden, and through their interactions with nature they discover meaningfulness and happiness in life.

But confidence in Western progress and empire was not faltering for everyone; certainly not for Rudyard Kipling, in whose stories the ideals of empire and manliness are celebrated, along with the code that public schools should train boys for their future role as rulers of the empire, as in Stalky & Co. (1899), which emphasizes the aggressive competitive aspects of boarding school as a preparation for life in colonial armies. Yet, for others, the strict moralizing lessons of Victorian times were becoming outmoded. There was an emphasis both on playfulness and on nurturing the imaginations of middle-class children, as we see in A Child’s Garden of Verses (1885), by Robert Louis Stevenson, which describes children absorbed in imaginary “make believe” games, boys transforming their surroundings through fantasy, turning meadows into jungles and populating a desert with pythons, pumas, and kangaroos.

It is hard to identify one clear literary trend: there was too much variety, intersecting and contrasting cultural trends, from the creative minds of British authors. Kipling also wrote Just So Stories (1902), fantastical tales encouraging children to wonder how animals came to evolve. Use of parody for comic effect can be seen in E. Nesbit’s Nine Unlikely Tales for Children (1901). Nesbit was a founding member of the Fabian Society who gained much attention with The Story of the Treasure Seekers (1899), of children who overcome perils through pluck, and The Wouldbegoods (1901), about a middle-class family fallen on hard times, which found great appeal for its special touch for depicting how children truly speak, feel, and behave. Then came J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan (1904), about a boy who refused to become an adult in an ideal world of daring and courage, interacting with fairies, pirates, and mermaids in a mythical paradise. And there was also Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902), a bestseller from the beginning, written in order to amuse a sick 5 year-old boy, about a rabbit, who disobeys his mother, combining humor, adventure, and a moral lesson.

In the period 1870-1914 American children’s literature is said to have “changed radically” both in the proliferation of books with greater variety of themes and characters and the high literary quality. The liberal trend to avoid “preaching” in children’s stories, in preference of amusement, story-content, and overall optimism about prospects in life and the possibility of finding happiness. Some say it was a “golden age,” characterized by such classic titles as The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), by Frank Baum; The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and Huckleberry Finn (1884), by Mark Twain. There were other classics in their own right. One was T.B. Aldrich’s The Story of a Bad Boy (1870), hailed as a departure in traditional children’s literature for showing boys as they were, rather than as they ought to be, which started a “bad boy” literature, of which Tom Sawyer was one, and so were C. D. Warner’s Being a Boy (1877), W.D. John Habberton’s The Worst Boy in Town (1880), and J.O. Kaler’s Toby Tyler: Or Ten Weeks with a Circus (1877). These stories, with their realistic images of boys as irrational, primitive, and masculine, attracted many readers. This genre is now criticized for encouraging “toxic masculinity” rather than “nice,” “caring,” “gender fluid,” and docile boys who listen attentively to their TikTok feminist teachers. In truth, these “bad boys” had an instinctive sense of what was right, rooted in small town America, with their own unique personalities built from hardship and assertiveness outside a standardized suburbia.

Girl school stories, or coming of age stories, were very popular. One was Margaret Sidney’s The Five Little Peppers and How they Grew (1881), about a widowed mother who has to sew all day to pay rent and feed five growing Peppers, which she does with a stout heart, a smiling face, and the help of her blue-eyed Ben, the eldest and the man of the house at the age of 11. America was still a land that celebrated independence and self-reliance, not from the standpoint of the isolated, atomistic selves, you see today addicted to social media, but within concrete local communities. Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (1903), by Kate Wiggins, was about a girl who is sent to live with her lonely aunt after her father died, to whom she brings her youthful enthusiasm and imagination, with poems and songs, selling soap to help a poor family, growing up to be a proper young lady with a kind heart.

Another book now considered a classic was Pollyanna (1913), by Eleanor Porter, with its innocent formula that we should be “glad, glad, glad” about everything however hard it may seem, a story about an orphan girl who remains positive and animated in spirit despite a hard childhood and later tribulations, spreading love and joy wherever she goes, and finding happiness in the end, thus proving that a good disposition and positive outlook can compensate for the hardships we face. This story was followed by 11 more Pollyanna sequels known as “Glad Books.” Another popular book was Little Lord Fauntleroy (1886), by Frances Burnett, about a boy who lives with his “Dearest” mother in poverty after the death of his father, who then inherits a British fortune, to be sent to live with the cold and unsentimental lord who oversees the trust.

Continuing Creativity Between 1914 and 1980

The period 1914-1945 in British children’s literature is downplayed as less original than the preceding periods—but didn’t J.R. R. Tolkien author The Hobbit (1937) and The Lord of the Rings (1937-49)? British education was still rooted in tradition, Western-centric standards, and great books. Rings drew on a combination of Christianity and Germanic heroic legend, including the Norse Völsunga Saga, the study of Old English literature, Beowulf, and on Celtic, Finnish, Slavic, and Greek mythology. Tolkien gained access to this pagan tradition in-through early Christianity, where it continued, not by resorting to some neo-pagan new age version.

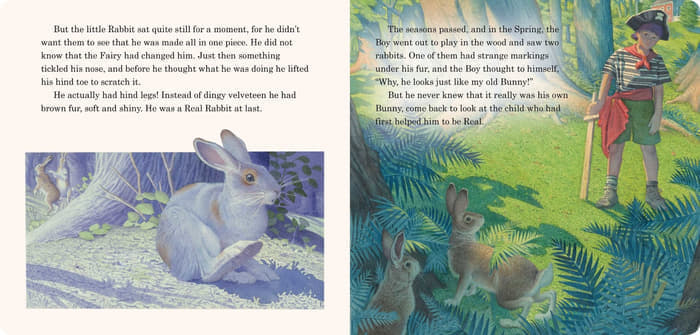

The early twentieth century saw many new children’s titles: 688 in 1913, which increased to 1,629 by 1938—despite WWI, the Great Depression, and WWII. They were mostly books for the comfortable middle class, not for the children of parents who participated in the General Strike of 1926, the same year the lovely story of Winnie-the-Pooh, by A.A. Milne, was published, about an optimistic, not very intelligent, but friendly and steadfast, teddy bear, with many other animal characters for children to identify with, Piglet, Tigger, and Roo. The Velveteen Rabbit (1922), by Margery Williams, was another popular book about a stuffed rabbit sewn from velveteen who becomes a boy’s favorite toy…but is thrown out of the boy’s house to become a real rabbit that the boy then encounters in the wild, showing how toy rabbits become real through the affection and imagination of children. Another classic was

The Story of Babar the Little Elephant (1934) about a baby elephant who flees the jungle after his mother is killed and moves into a big city where he is civilized and dresses in Western attire. The West was still unwilling to devalue its imperial history. Postcolonial theory was still in the future. The Lockean call for affection towards animals had nurtured uniquely Western stories of animals that live like humans, with human qualities coupled with toys in the shape of animals like a Teddy Bear or Babar dressed up like a human.

Long running series of stories for boys and girls were common: M.E. Atkinson’s August Adventure (1936), Elizabeth Yates’s High Holiday (1938), Francis Joyce’s Yes, Cousin Joseph (1935), and Elizabeth Brent-Dyer’s The School at the Chalet (1925) with its fifty seven sequels! The trend-setting writer of “modern schoolgirls’ stories” was the British Angela Brazil, author of some 50 boarding school books, beginning with The Fortunes of Philippa (1906). The Nicest Girl in The School (1909) sold 153,000 copies. Brazil was raised by a mother critical of the “traditionalism” persisting in Victorian English schooling, determined to raise her children according to the Lockean principle that children who experience a liberal education in literature, music, and science will become creative and nurturing. Notwithstanding the prior influence of Locke in intellectual circles and in the writing of children’s books, a traditional moralism continued to prevail in Victorian England about self-sacrifice for the nation, the moral virtues of patriarchal families, and the importance of abiding by Christian norms. Brazil’s books portrayed “independent-minded” female characters who openly challenged authority, were impertinent, enjoyed pranks, and expressed their youthfulness without worrying about the rigidified concerns of adults.

Children’s literature 1945-70 is characterized by historical realism, fantasy/science fiction, and “internationalism.” Kipling-type books eulogizing British imperial manliness gave way to books in tune with “the egalitarian, post-colonial mood” of a Britain without an empire. However, despite promotion of “international exchanges” and a few books about minorities, this period remained creative, even as it was undermining the conditions that made this creativity possible. As TV became a major form of recreation, authors came to de-emphasize this aspect of children’s books in favor of literary quality—for the newly constructed public schools and libraries. The rising literary status of children’s books is reflected in the growth of literary reviews, book awards, and new journals, such as Children’s Literature in Education. It is said that the 1950s and 1960s was “a period of exceptional artistic license for the children’s author”—because, while the prescriptive morality of the Victorian era had dissipated, the “new agenda of political correctness in matters of sex, class, and race” was still in the future, so authors were “unusually free of pressures to promote approved conformities.”

Incorporating historical research became popular. Irene Hunt’s Across Five Aprils (1964) integrated historical facts into stories she heard from her grandfather about family experiences during the American Civil War. Elizabeth Speare’s, Calico Captive (1957) was about a girl kidnapped by an Abenaki Indian raid on Charlestown in 1754. Jean Fritz’s book, George Washington’s Breakfast (1969) was about a boy determined to learn everything he could about his namesake, including what the first president ate for breakfast. Cynthia Harnett wrote novels, such as The Wool-Pack (1951) and The Load of Unicorn (1959), about daily life in Medieval England. Henry Treece’s The Dream Time (1967) was set in prehistory, about a boy with a bad leg cast out from his tribe because of his ability to draw wonderful (but forbidden) pictures, who embarks on a journey meeting many peoples including the last of the Neanderthals. Alan Garner’s The Weirdstone of Brisingamen (1960) uses Norse mythology to bring clarity to a child’s perception of the confusions of modern life.

Science fiction flourished. Science fiction is a modern Western genre (not to be confused with the fantasy genre) that originated as writers began to envision in the course of the industrial revolution how the world would be as technology developed continuously into the future. Its basic themes include prophetic warnings, utopian longings, imaginary worlds, titanic disasters on earth, strange voyages. H.G. Wells (1866-1946) is a founder of this genre. The best children’s sci-fi books of this period include The Martian Chronicles (1950), by Ray Bradbury, a fascinating story about Americans who conquer Mars, the home of indigenous Martians, followed by the conquest of the Earth, by Martians, with the apocalyptic destruction of both Martian and human civilizations, both instigated by humans consumed by their militaristic scientific power. In contrast, Eleanor Cameron’s The Wonderful Flight to the Mushroom Planet (1954) reflected an optimistic view about the possibilities of science, being a story about two boys who, upon reading a newspaper advertisement looking for a home built spaceship, decide to build one out of tin and scrap wood, which they then bring it to the advertiser, an inventor who makes a few improvements, gives them a special fuel, and tells them they must visit the mushroom planet, which is really a tiny habitable moon orbiting the Earth invisible to normal telescopes. This moon is covered in giant mushrooms and populated by small men with large heads and light green skin, who tell the boys that everyone on their planet is dying of a mysterious illness. The boys end up solving the natives’ problem before returning to Earth. Peter Dickinson’s trilogy, The Weather-Monger, Heartsease, and The Devil’s Children (1960/70) depict a repressive Britain in which machines are banned and people return to a primitive lifestyle. In fantasy, we must at least mention The Chronicles of Narnia (1950-56), a series of seven novels by C. S. Lewis, which has now sold over 100 million copies in 47 languages. These stories call upon children to imagine what would happen in a land like Narnia where the Son of God, who became a Man in our world, became a Lion, seen as a marvelous retelling of Bible stories in a new Pagan way.

Post 1970: Blank-Slate Children without Families and Civic Communities

During the 1970s there is a noticeable trend in children’s literature towards “black pride,” “female heroes,” “interracial friendship” and “empathy.” In 1965 the Saturday Review published an influential article with the title: “The All-White World of Children’s Books.” This article sounded reasonable. If the US was founded on equal natural rights, and blacks have been an intrinsic component of this nation, should they not be reflected in children’s books? This article was not attacking whites as such, but asking whether the books at the time reflected the experiences of black children. This was just the beginning, however, of what would become a massive ideological movement aimed to transform the themes and contents of children’s literature, well beyond equal civic rights. In the late 1970s, some authors of children’s books expressed concern about the “censorial imposition” of “guidelines” over the use of “non-sexist” and “non-racist” language.” These guidelines began as mere “requests for tools” to eliminate “bias” in literature and include nonwhites in stories. A few decades later these demands would be radicalized into demands across all schools for “Books to Teach White Children and Teens How to Undo Racism and White Supremacy“.

The time was ripe for the complete indoctrination of children. Children were becoming more isolated than ever, as the nuclear family, the last bastion of blood identity, the “All-American Family” eulogized in the 1950s, was discredited as the US started to “embrace more progressive politics”. This was a time when the divorce rate started to rise, and a growing proportion of young adults began to postpone and then forgo marriage altogether. In Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (2000), Robert Putnam noted a dramatic decline, from the mid-1960s onwards, in membership and number of volunteers across a wide spectrum of civic organizations, such as religious groups, labor unions, parent–teacher associations, military veterans’ organizations, volunteers with Boy Scouts and the Red Cross, and fraternal organizations. In other words, liberalism was now undermining the very civic (contractually created) communities it had created in place of the old kinship tribal communities. A few years later, Putnam released the results of a comprehensive survey of over 30,000 respondents around the US, in which he “found that the greater the diversity in a community, the fewer people vote and the less they volunteer, the less they give to charity and work on community projects. In the most diverse communities, neighbors trust one another about half as much as they do in the most homogeneous settings. The study, the largest ever on civic engagement in America, found that virtually all measures of civic health are lower in more diverse settings.”

The minds of children were emptied more than ever of any traditions, family experiences, and even attachments to liberal-created civic communities. Not surprisingly “chronic loneliness” is now “a modern-day epidemic,” with “rates of depression and anxiety among teenagers increasing 70 percent in the past 25 years.” Children today are incredibly vulnerable to ideological manipulation, which has coincided with a massive increase in the number of new children’s book published in the US: from 2,001 in 1971 to 3,214 in 1979, and to 6,154 in 1991, and then to 21,878 new titles in 2009. It is not that good writers disappeared after 1970. Richard Adams’s highly popular Watership Down (1972) was an old-style animal adventure story in which a small band of male rabbits with their own history, language and mythology set out to start a new warren, facing numerous hardships, rescuing female rabbits from an evil rabbit to bring them to their warren, living happily ever after. Roald Dahl, author of the famous Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964), and numerous stories told from the point of view of a child’s imagination, also wrote The Witches (1983), criticized today for its “misogyny,” a dark fantasy featuring experiences of a boy and his grandmother in a world where child-hating societies of witches secretly exist in every country.

High quality historical fiction continued through the 1970s into the 1990s, even as it came increasingly with some PC motivations. Rosemary Sutcliff, the author of many great 1960s stories, such as Outcast, which tells the story of an orphaned child in Roman Britain who is shipwrecked on a coast outside of Roman rule, continued to write excellent retellings of myths and legends, including Song for a Dark Queen (1978), about the tragic life and military campaigns of Boudicca, Queen of the Iceni, against the Romans. Penelope Lively’s historical fantasy novel, The Ghost of Thomas Kempe (1973), about a ghost of a 17th-century resident, encouraged children to become aware of “layers of memory of which people are composed.” Jill Walsh’s A Parcel of Patterns (1983) is about a girl living in 1665, in a village, who tends her flock and teaches her young suitor to read, when one day a parcel of patterns, meant for a new dress for the pastor’s wife, arrives from London, carrying an infection that spreads with horrifying speed.

But the seeds of political correctness could not be stopped from giving birth to a generation of “progressive” authors. Robert Leeson’s historical trilogy, Maroon Boy, Bess, and The White Horse (1975-77), were intended to “fight against the oppression of black people, of women, and working people” in the present. The literary critic, Patrick Parrinder, stated that the aim of science fiction should be “social criticism” and the creation of a more progressive culture. Richard Peck’s Are You in the House Alone? (1976) was about a babysitter raped by one of the most respectable boys in town, that is, a white privileged boy. Autumn Street (1977), by L. Lowry, is a “candid and memorable” story about an interracial relationship. Again, these stories were still reasonable in comparison to what was about to be unleashed upon the fragile minds of children. Barbara’s Ashley’s The Trouble with Donovan Croft (1974) is about a black boy who loses his ability to talk when he is raised by a white family because he can’t stay at his own house because his mother has gone back to Jamaica to care for her dying father—it deals with racism towards Donovan because of his immigrant Jamaican heritage. William Maynes’s Drift (1985) narrates a journey from the point of view of a white boy and then from that the view of an Indian girl with the intention of showing the “often limited quality” of the white view. Mary Hoffman’s Amazing Grace (1991) is an “empowering” book about an African-American girl with the message that she can be whatever she wants to be, regardless of what other people say, if she stays true to herself as a black girl.

But increasingly in the 1990s and 2000s, books instructing children that blacks were “victims of systemic white racism” would proliferate. Unimaginative, simplistic children’s books “about race and racism” now prevail in school curricula. As the West committed itself to mass immigration, the educational establishment coordinated its efforts to fill up the blank-slate minds of children with the slogan that “diversity is our greatest strength.” Government offices, the mainstream media, the journals, everyone in charge of education, began to dictate what was “appropriate reading” for children, reaching the conclusion that the most important way to educate them was to produce “Resources for Race, Equity, Anti-Racism, and Inclusion.” White children needed to be raised with guilt as a means of preparing them to inhabit a diverse world with proud immigrants. With the decline of the family, demands grew against stories that assumed that monogamous nuclear families with married fathers and mothers were “normal” rather than an “illiberal” prejudice. LGBTQ books skyrocketed, coupled with a dramatic decline in the quality of children’s literature, fluffy stories calling upon white children to be “kind,” “nice,” and “empathetic” through vibrant rainbow colors.

This is not to say that good books, great fantasy stories, ceased after the 1990s. Many classic stories continued to be published. Books written under the pen name “Dr. Seuss” in the 1950s and 1960s—The Cat in the Hat, How the Grinch Stole Christmas!, Green Eggs and Ham—gained in popularity. Who can ignore the explosive epic fantasy series that began in 1998 with the publication of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, successfully adapted to blockbuster movies, a story about a wizard boy set in a magical boarding school? The Harry Potter series authored by J.K. Rowling “is far and away the highest-selling series of novels ever, selling over 500 million copies, 150 million more than the next-highest selling series.” Despite their length, many children enjoyed reading them, combined with the movies and the merchandise. Through all the wizardry and sorcery, the series emphasized standard values like friendship, humility, and bravery. Harry Potter was politically correct in its day, shining “a light on some surprisingly dark themes such as mental health and LGBT visibility.” But now the author Rowling is not so correct, provoking in recent years controversy “as a person who sees herself as a progressive due to her feminist values…but refuses to extend those values to…trans people in general.” “It’s Time for Progressives To Move On from Harry Potter,” opined Miles Schneiderman. The series, and the movies thereof, also came to be criticized for their “outrageous lack of diversity.”

It is time to embrace Marvel’s Black Panther children’s book series for “providing a lesson in diversity and representation in its celebration of black culture with an almost all-black cast.” As an “avenger of civil rights,” the “MacArthur Genius and National Book Award winner” Ta-Nehisi Coates joined the Black Panther series in 2016, contributing a number of children’s books, including A Nation Under Our Feet, a story about “the indomitable will of Wakanda—the famed African nation known for its vast wealth, advanced technology and warrior traditions.” The Guardian noted in 2019 a “seismic shift” in the number of books by and about “Blacks,” “Asians or Asian Americans,” “Latinx,” and “First Nations.” This shift is inescapably tied to immigration replacement. A heavily-funded, institutional network, with full time salaried bureaucrats, has no other motto but that we need more diverse books.

Classic books are barely read in our schools nowadays. Many of the pre-1990s books listed above only make it as subjects in literary analysis about “How to Break Up with Your Favorite Racist Children’s Books.” The list of books getting cancelled include The Secret Garden, Huckleberry Finn, The Little House on the Prairie, Peter Pan, Peter Rabbit, Cinderella, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, and the Chronicles of Narnia. The latter was cancelled on the grounds that it “takes place in the northern regions of a world composed mostly of white people.”

We could go on with this depressing conclusion to the otherwise noble history of children’s literature. The way liberalism, through to the modern era, until a few decades ago, encouraged a highly gifted genealogy of children’s stories deserves our attention and admiration. It seems that liberalism remained a creative and positive force in the West so long as it was supported by family values, continuation of traditional Christianity, and, yes, strong civic communities and associations. It is a complex subject we only covered on the surface: why are Western educators disowning their magnificent legacy of children’s literature, replacing it with contrived stories promoting the sexualization of children and hatred towards their ancestors? Was liberalism bound to culminate in this situation?

Ricardo Duchesne has also written on the creation of the university. He the author of The Uniqueness of Western Civilization, Faustian Man in a Multicultural Age, Canada in Decay: Mass Immigration, Diversity, and the Ethnocide of Euro-Canadians.

Featured: “Ein kleiner Bücherwurm” (A Little Bookworm), by Eduard Swoboda; painted ca. 1902.