The following was published a few years ago – but in a very different version. We are publishing a significantly updated version, which the author has fully elaborated with the benefit of hindsight.

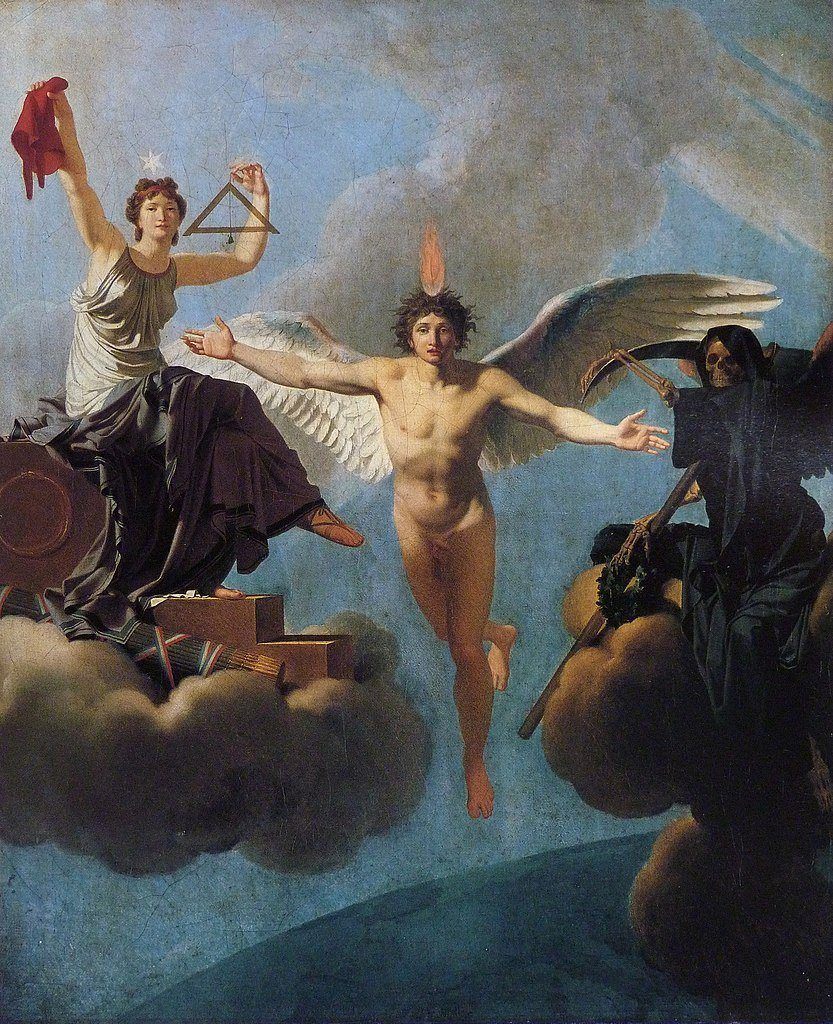

The obsession of liberals [libertarians, either “classical liberals” or “anarcho-capitalists”] to condemn only economic or “cultural” Marxism is a dead end. Saving Western civilization requires the wisdom to identify, and the courage to name, the other contemporary enemy of the West: namely cosmopolitanism. Cultural Marxism – in the sense of Antonio Gramsci’s doctrine that Marxists must reach cultural hegemony before attempting the Revolution – is certainly influential in the West; but not more than is cosmopolitanism itself – in the sense of the doctrine that political and moral boundaries must be dissolved for the benefit of the individual’s “emancipation.”

Economic Marxism – in the sense of communism (or semi-communism) and planning within a national framework – is certainly on the rise again in China; but China itself is an ally to the global superclass promoting cosmopolitanism. The “global superclass,” according to the expression popularized by Samuel Huntington, consists of a transnational network of uprooted and denationalized people, whose gestation dates back at least to the beginning of the 20th century and whose constitution accelerated with the fall of the Soviet bloc. Here, we will seek to elucidate the conceptual relations between liberalism [libertarianism] and cosmopolitanism; and will outline the contours of a new variety of liberalism – namely a liberalism simultaneously directed against bourgeois nationalism and against cosmopolitanism.

Definition Of Cosmopolitanism

By cosmopolitan ideology, one must understand here an ideology that rejects humanity divided into nations. As such, cosmopolitanism condemns the particular mode of organization that characterizes a nation as a nation, i.e., which confers on a group of individuals the identity and the unity of a nation. This unity consists of the following: a relative genetic homogeneity, as well as cultural one; a chain of social and juridical tiers that goes back to a sovereign political authority (i.e., the supreme authority within the government); and a territory that is covered by, and which limits, that hierarchical and homogeneous organization.

Cosmopolitanism attacks national territory, and therefore borders, by forbidding governments to defend nations against indiscriminate free trade or free immigration. It also attacks the juridico-political hierarchy of a nation, either by calling for inequalities reduced to income, merit, and occupation inequalities, or in advocating the substitution of nations with a world government. Finally, cosmopolitanism condemns as much the admitted moral frontiers (between good and evil, beauty and ugliness, honor and dishonor) as the genetic and cultural differences between nations. Not content with advocating the relativism of values (i.e., the abolition of moral boundaries), it praises the leveling of races and cultures.

It is a mistake to believe that the cosmopolitan elite would subscribe to the ideal of a humanity reduced to its animality, i.e., a humanity in which only the spontaneous (rather than diverted) aspirations of those instincts we inherited (from our primate ancestors) are expressed in human behavior – and expressed only in an unleashed (rather than rationalized) manner.

In effect, the ideology of the world superclass abhors the spontaneous aspirations of those human instincts that are expressed as territory and domination, identity and adventure – or even abhors those instincts as such, which come as distinct modalities of the aggressiveness coded in our genome.

The ideal inspiring cosmopolitanism is actually that of a humanity in which the spontaneous aspirations of our instincts for territory and identity – and therefore the attachment to frontiers – are no longer expressed. And of a humanity in which the spontaneous aspirations of our instincts for adventure and domination – and therefore the taste for military, economic, or intellectual competition – are no longer expressed. A humanity deprived of its national and cultural rooting, but also, more fundamentally, of its biological rooting – that is the horizon of the cosmopolitan ideology.

In the area of values and moral boundaries, let us point out that the version of cosmopolitanism advocated by the world superclass diverges from pur et dur cosmopolitanism. The ideology of the world superclass indeed counterbalances the call to get rid of any moral boundary (on behalf of individual emancipation) with the concern for preserving some of the typically bourgeois values – as much as with the concern for promoting ecologism and worldwide communism.

The wording “cosmopolitanism” was brandished for the first time by the Cynic philosopher Diogenes of Sinope. Nonetheless, we will leave aside the question of knowing whether Diogenes understood “cosmopolitanism” in its current sense of an ideology which preaches the relativism of values and the leveling of races and nations; or rather, for instance, in the sense that everyone – at a moral and biocultural level – belongs (and must belong) to a given nation, while belonging to the entire humanity at a “spiritual” level.

The Stoic philosophers and the Alexandrine Jewish philosophers were certainly partisans of the federation of nations under the aegis of a certain universal law. Nonetheless, they were not cosmopolitan in the current sense, i.e., they were not proponents of the dissolution of nations under the aegis of moral relativism.

What will concern us here will be cosmopolitanism as it is currently understood – and as it adapted and set up by the world superclass. Also, we will examine liberalism envisaged in its relation to the world superclass’s cosmopolitanism, i.e., the world superclass’s ideology advocating biocultural leveling and a certain moral relativism, but remaining attached to those bourgeois values that are the priority pursuit of material subsistence and the materialist approach to reality.

The Three Heads Of The Equalitarian Hydra

The overwhelming majority of liberals (be they academics or simply followers of the liberal philosophy) refrain from denouncing cosmopolitanism and envision Marxism as the only enemy to fight. What is more, they indulge in cosmopolitanism at various levels, whether or not they use the term cosmopolitanism – and whether that ideological leaning is conscious on their part or is so natural that it goes unnoticed in their own eyes. Does this mean then that liberalism conceptually ends up as cosmopolitanism? In other words, that cosmopolitanism comes as the logical outcome of liberalism, and that the endorsement of cosmopolitanism among liberals is – conceptually – necessary rather than contingent?

Before we answer these questions, it is important to highlight the kinship of liberalism, socialism, and cosmopolitanism. Those three ideologies (or philosophies) are ultimately the three distinct manifestations of the same egalitarian ideal.

Liberals, socialists, and cosmopolitans are indeed “in-fighting relatives,” animated by a common passion for (arithmetical) equality. And that, even though it is a faith, an ideal, which they proclaim in three distinct ways (universality of law for liberals; equality of incomes, or, at least, equal subjection to central planning, for socialists; the leveling of races and nations for cosmopolitans – let us add that liberalism, socialism, and cosmopolitanism – as they have unfolded since the French Revolution – also converge in their common adherence to the hegemony of economy in the scale of values. Such hegemony is not wishful thinking on the part of egalitarian ideals.

Concomitantly, with the dissipation of intermediate juridical inequalities (in accordance with the liberal ideal of equality in law), economy has lifted itself – in the wake of the Revolution of 1789 – at the summit of Western values. On the same token, the welfare state has gained ground (in accordance with the socialist ideal of economic equality); and concomitantly with the rise of the world superclass, cosmopolitanism itself has finally contaminated the intranational mores and the relations between nations. The world superclass also promotes ecologism, transhumanism, and communism – but here we will leave aside those aspects of the world superclass’s ideology.

Let us be clear about what makes the singularity of each of the three faces of the equalitarian ideology. The universality of law – or the equality of human beings with regard to the rules of law that must apply to them – serves as the fundamental categorical value of liberalism. In other words, liberalism fundamentally promotes the value of equality taken in a legal sense, i.e., taken in the sense of the equal freedom of all, the equal right of all not to suffer coercion (towards their life or their peacefully acquired goods).

For socialism, it is equality in an economic sense, i.e., income equality and central planning, which serves as a fundamental categorical value.

And for cosmopolitanism, it is equality taken in a biocultural and “communitarian” sense: the equality of men in the sense of their biological and cultural indifferentiation – and in the sense of their non-belonging to another collective than Humanity. That everyone be culturally and racially identical, and that no one be a member of a nation within Humanity; that everyone be a member of Humanity considered as a collective in its own right (and that he be a member of that collective only), and that the individual be released from the moral boundaries that his affiliation to one or other nation assigns to him; and finally that everything which “thwarts” and separates individuals be removed., That is the egalitarian creed of cosmopolitanism.

From Classical Liberalism To Anarcho-Capitalist Cosmopolitanism

In its purest form, so to speak, liberalism merges with an anarchism that respects private property – including the private ownership of the means of production. That said, it is an insoluble problem of knowing whether the “true” manifestation of a political movement lies in the “extremist,” fully coherent (doctrinally speaking) branch of that movement, or lies instead in a moderate, “pragmatic” branch of the latter. Determining whether the “true” implementation of a doctrine lies with the radical branch of its proponents (or lies instead with a moderate branch) falls within arbitrary consideration, “subjective preference.”

Therefore, it would be futile to ask whether the movements promoting anarcho-capitalism are “truer” than those promoting classical liberalism. But it is not futile to try to determine whether integral liberalism, in addition to being wholly anarchist, is wholly cosmopolitan (out of conceptual necessity). We shall see that anarcho-capitalism only exacerbates the amount of cosmopolitanism already present in classical liberalism – but that both anarcho-capitalism and classical liberalism remain distinct from integral cosmopolitanism.

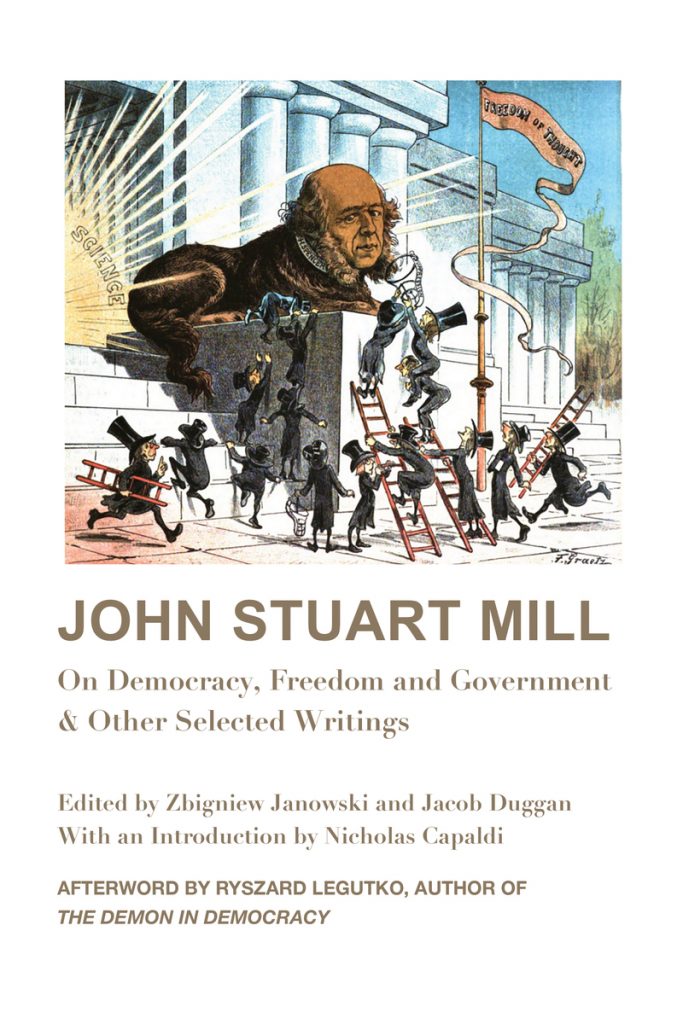

Classical liberalism (that of John Locke, Adam Smith, J-B. Say, Mill, father and son, Robert Torrens, Frederic Bastiat, Yves Guyot, Ludwig von Mises, or Friedrich A. von Hayek) does not only affirm its attachment to equality in law, i.e., universality of the rules of law, universal freedom of all – but it promotes an extended division of labor and praises the entrepreneur as the one who coordinates the division of labor (on the basis of his anticipation of the fluctuations in demand), and who spurs the allocation of factors in anticipation, and in the direction of, the long-term equilibrium – that is, the type of equilibrium where capital is used and allocated in such a way that, besides the equilibrium market prices corresponding perfectly to the entrepreneurial anticipations, each factor is used and allocated in the most satisfying manner in view of current expectations on the part of consumers and investors.

Anarcho-capitalism inhabits the same terrain as classical liberalism, except that it rejects the “minimal state” promoted by classical liberals – and instead calls for privatizing (and opening up to competition) the “regalian” functions, i.e., putting an end to the state’s legal monopoly on the use of force to sanction attacks against physical integrity and against property rights.

The greatness of classical liberalism (which culminates in anarcho-capitalism) lies in its double demonstration of the superior productivity of an extended division of labor and of the need for the free market – a fortiori the free market for capital goods, in the absence of which there can be no anticipation and no calculation on the profitability of allocation decisions – to extend the division of labor and to coordinate it in the direction of the optimal satisfaction of consumption and investment needs.

The mediocrity of classical liberalism notably lies in its contempt for the practice of war – and in its pacifist ideal that degrades human nature, for it is true, as Hegel knew so well, that “the movement of the winds preserves the waters of the lakes from the danger of putrefaction, which would plunge them into a lasting calm, as would do for the peoples a lasting peace and a fortiori a perpetual peace.”

As for the relations between Western nations, the pacifism of classical liberalism eventually triumphed after the end of the Second World War. But the disappearance of war among Western nations only completed the preliminary disappearance of what may be called the individualist conception of war – or the Indo-European ethos in the practice of war. We will turn to that issue a bit later.

Anarcho-capitalists, like classical liberals, by the very necessity of their doctrine, indulge, to some extent, in cosmopolitanism, which, let us recall, is defined (in its complete form) by its call to abolish moral boundaries, to dissipate political boundaries, and to level races and cultures. While classical liberalism merges with a relative cosmopolitanism, anarcho-capitalism merges with a more pronounced cosmopolitanism (which remains incomplete).

Classical liberalism accepts, to some extent, the existence of nations. It accepts them except it promotes the indiscriminate opening of borders to goods and to migrants (in the name jointly of freedom and of the ideal of a division of labor whose scope transcends political boundaries) – all the while prohibiting (on behalf of freedom) any coercive measure intended to preserve biocultural identity.

For its part, anarcho-capitalism accepts biocultural homogeneity in a group of people; but it refuses the existence of nations as political edifices (if not as biocultural entities). The reason for this refusal lies in the fact that anarcho-capitalism finds all the implications of equality in law, which is tantamount to saying that it aspires to an equality in law that it be perfect, or “die-hard.”

As for moral boundaries, both anarcho-capitalism and classical liberalism promote bourgeois values – although they do not necessarily call them “bourgeois,” and although they claim such values to be universally adapted to human beings (rather than adapted to the sole bourgeois type of man). These values include the categorical (equality before the law), and the instrumental or conditioned ones, which are intended to set up the (bourgeois idea of) “good life.” Ayn Rand rightly summed up the bourgeois conception of the good life as the peaceful “survival of man as a rational being.” We will at this concept, and the instrumental values it implies, a little later. For now, let us simply note that classical liberalism, like anarcho-capitalism, are cosmopolitan to some extent with respect to political boundaries – and that anarcho-capitalism and classical liberalism are axiologically engaged with cosmopolitanism, rather than being morally cosmopolitan.

Classical liberalism, as it accepts the state, accepts a first infringement of equality in law. Officials and taxpayers, indeed, do not see themselves judged by the same rules of law in the sense that the former are exceptionally empowered to live on coercion and to enjoy privileges, such as, the more extended right to strike, very advantageous pensions and health care benefits, or guaranteed employment.

However, classical liberalism does not only accept the state; it accepts the state within a national framework. In other words, it accepts the state as territory of a given nation, federated by a relative cultural and genetic homogeneity. With notable exceptions, like Mises, classical liberalism does not promote the disappearance of national states for the benefit of a world state. As such, in addition of accepting the inequality in law between civil servants and taxpayers, classical liberalism accepts the inequality in law between domestic residents and foreigners. Yet anarcho-capitalism does not even want those two infringements of equality in law. The only inequalities that it deems legitimate are the inequalities of income, diploma, and profession. And that, because it regards any inequality in law as a fault, including the distinction between the official and the taxpayer and the one between the national citizen and the foreigner.

The relative cosmopolitanism that characterizes classical liberalism, and the adherence to a world government are both perfectly clarified by Ludwig von Mises, his treatise, Liberalism: “The metaphysical theory of the state declares – approaching, in this respect, the vanity and presumption of the absolute monarchs – that each individual state is sovereign, i.e., that it represents the last and highest court of appeals. But, for the liberal, the world does not end at the borders of the state. In his eyes, whatever significance national boundaries have is only incidental and subordinate. His political thinking encompasses the whole of mankind. The starting-point of his entire political philosophy is the conviction that the division of labor is international and not merely national. He realizes from the very first that it is not sufficient to establish peace within each country, that it is much more important that all nations live at peace with one another. The liberal therefore demands that the political organization of society be extended until it reaches its culmination in a world state that unites all nations on an equal basis. For this reason he sees the law of each nation as subordinate to international law, and that is why he demands supranational tribunals and administrative authorities to assure peace among nations in the same way that the judicial and executive organs of each country are charged with the maintenance of peace within its own territory.”

Anarcho-capitalism condemns the official and the taxpayer, along with the national citizen and the foreigner. Although anarcho-capitalism is necessarily cosmopolitan only in part (and necessarily condemns moral relativism), anarcho-capitalist cosmopolitanism is however a much more asserted, much more radical cosmopolitanism than classical-liberal cosmopolitanism.

As for biocultural identity, both anarcho-capitalism and classical liberalism necessarily oppose coercive measures intended to preserve the latter – for instance, a ban on miscegenation, which is not tantamount to morally approbating miscegenation (or the loss of biocultural identity generally speaking).

That said, one cannot but notice – in addition to those cosmopolitan tendencies that flow from a conceptual necessity – the following propensity on the part of anarcho-capitalists in practice – namely, their propensity to deny the existence of the aggressive instincts (i.e., identity and territory, adventure and domination), as well as the existence of races and cultures – and to morally condone, or even encourage, cultural leveling and miscegenation. And that, on the grounds that there should only exist “individuals” – that is, individuals who are not only born tabula rasa and undifferentiated, but who have no other social link than the division of labor and trade, the genetic and cultural links of the nation being denied in particular.

Such an approach deserves, in our opinion, the qualifier of “liberal Lysenkoism.” It is found among anarcho-capitalist but also among hybrid liberals, i.e., those liberals who are allied to the minimal state (or minarchy) of classical liberalism and who are nevertheless seduced – like are anarcho-capitalists – by the ideal of racial, cultural leveling.

From The National-Liberalism Of 1789 To Pseudo-Nationalist Anarcho-Capitalism

Pure radical liberalism can be defined as egalitarianism which – on behalf of the equal freedom of all – recognizes as legitimate sole economic and academic inequalities, i.e., income, diploma, and occupation inequalities.

Among anarcho-capitalists, some however care (more or less openly) for the coercive preservation of biocultural identities – and endeavor to develop a system that reconciles the coercive preservation of biocultural identities with the universality of law. Such is the case of Hans Hermann Hoppe especially.

Such version of anarcho-capitalism remains a modality of cosmopolitanism – and therefore, a modality of liberal cosmopolitanism, i.e., a cosmopolitan modality of libertarianism. Nevertheless, there is indeed a liberalism that reconciles the ideal of the nation, the rejection of all sorts of cosmopolitanism, with equality in law, i.e., the equal, universal freedom of all – and that liberalism is none other than the one which inspired the Revolution of 1789 and the posterior European nationalisms.

We have seen that classical liberalism affirms the existence of nations and advocates that they cultivate pacifism and free trade – and that they reject warmongering for the benefit, not only of peace, but of a social division of labor that limits nothing and which extends beyond frontiers. In other words, one in which men and capital circulate without the slightest restriction.

The national-liberalism of 1789, which serves as the matrix of the various European nationalisms of the 19th century, differs from classical liberalism on the question of free trade and free immigration. Unlike classical liberalism, it does not intend, indeed, to open borders to goods and people indiscriminately. It is also parts company with classical liberalism on the question of pacifism. Napoleonic imperialism and the conflict of 1914-1918 came as grand manifestations of the warmongering inherent in bourgeois nationalism. The disagreement between classical liberalism and national-liberalism over pacifism reflects one more fundamental of bourgeois values. The latter include, on the one hand, a categorical principle, namely, the equal freedom of all, and on the other hand, a series of instrumental principles (i.e., social division of labor, non-violence, responsibility, frugality, etc.) that allow for the bourgeois conception of the “good life,” i.e., peaceful and rational material subsistence.

While classical liberalism and anarcho-capitalism wholly subscribe to these principles, the national-liberalism of 1789 counterbalances its subscription to these principles with its endorsement of what may be called a gynecocratic cult of the nation, i.e., a veneration of the nation as a motherly deity, all of whose children are equal – and equally expected to die anonymously for the nation on the occasion of wars. Thus, the national-liberalism of 1789 – while enshrining bourgeois values within the nation – adheres to the infringement of the bourgeois prioritization of material subsistence, when it comes to the relations between the nations.

Besides, the national-liberalism of 1789 combines the ideal of free enterprise with that of a perfectly unified nation, i.e., one deprived of its intermediary bodies and its intermediary rank inequalities. It intends to exacerbate national sentiment so that the feeling of belonging to some nation henceforth arouse a greater pride than that of belonging to some caste or some class within that nation. It also seeks to erode the traditional intermediate inequalities of status, so that the nation only knows inequalities in income and in profession – and thus reducing individuals to mere cogs in the division of labor.

The national-liberalism of 1789 also promotes a policy of cultural homogenization. For example, by combating regional dialects and imposing the use of a single “national language.” It can even promote the unification (into a single nation) of a geographical area, and being composed of culturally and genetically related nations. Italy and Germany offer us two eminent examples of such unification. In line with its attachment to political measures intended to increase cultural homogeneity, the national-liberalism of 1789 can also promote political measures intended to preserve biocultural homogeneity.

Apart from the forced unification of a region (into a single nation), the forced cultural homogenization, and the forced preservation of biocultural identity; as well as apart from the counterbalancing free enterprise (and the extended social division of labor) with restrictions to free trade and free immigration, and apart from the counterbalancing the bourgeois ethos of prioritizing material subsistence with the principle of forced self-sacrifice for the sake of the motherly nation – the national-liberalism of 1789 converges with classical liberalism as to the promotion of bourgeois values. As Vilfredo Pareto invites us to do, it is always worthwhile to distinguish between the “residue” and the “derivation,” i.e., the (sometimes instinctual) feelings that any ideology serves and the rhetorical tricks it hypothetically uses to conceal those feelings – or to conceal the compromises with reality that the ideology in question is hypothetically obliged to make.

In fact, the national-liberalism of 1789, which claims its strict attachment to bourgeois values and equality in law, endeavors to legitimize (and enshrine) a society that does not ignore inequality in law, but only intermediate bodies and intermediate castes (between the government and the individual), in which juridical, economic, and academic inequality is such that the ruling class is henceforth the bourgeoisie. What is more, such a society is not fully absorbed by the priority pursuit of mutual, peaceful subsistence between formally equal proprietors, but which counterbalances that bourgeois ethos with the principle of compromising one’s material subsistence (and the smooth running of the social division of labor) for the sake of the national gynecocratic cult. The national-liberalism of 1789 endeavors to defend the bourgeois juridico-political edifice – and the gynecocratic, sacrificial wars of bourgeois nations – under the guise of a mysticism of peace and equality.

A certain version of anarcho-capitalism, which may be called pseudo-nationalist anarcho-capitalism, takes into account biocultural identities – and paradoxically intends to preserve them coercively. The anarcho-capitalism à la Hoppe indeed conceives of the anarcho-capitalist order as a “covenant,” jointly based on property right and on the contractual obligation to verbally, behaviorally adhere to a certain set of “conservative” values. Therefore, anyone formulating ideas contrary to those values, or behaving in contradiction with them. is likely to get expelled from the “covenant,” though the latter is established in a wholly peaceful, voluntary manner.

Hoppe (to the best of our knowledge) does not raise the following implication openly – that such an anarcho-capitalist “covenant” – besides allowing the rallying around some shared values (which are, in fact, the bourgeois values) – also allows for the coercive preservation of biocultural identity. For instance, through the conceivable contractual obligation not to miscegenate oneself – or the one not to convert to Islam. As for immigration (whose political channeling is part of the coercive measures to protect the nation’s biocultural identity), Hoppe makes the case that a policy authorizing indiscriminate free immigration is necessarily incompatible with the enforcement of property rights. On the grounds that such policy violates the right of proprietors to decide who is entitled or not to cross the limits of their respective properties.

At first sight, the Hoppean covenant may look like an honorable, though chimerical, attempt to reconstruct the nation in an anarcho-capitalist framework. Actually, such is not Hoppe’s intent. And rightly so – for one cannot overestimate the inanity of that conceivable intent. National boundaries are, indeed, not enshrined by the owners themselves (as is the case in the Hoppean covenant), but by the governments. Nonetheless, the nation is not a fantasy used by governments (to legitimize their authority over a given territory) no more than it is created by a voluntary association of coowners. What necessarily characterizes a nation (as a nation) is that it comes as a certain space, federated by a given pecking order, a certain juridico-political order, and by a territorial instinct which is expressed as much among those “at the bottom of the social ladder” as among those who compose the ruling class and the state administration. A certain space which is, besides, occupied by people who are genetically homogeneous – as well as culturally homogenous – to some extent, and who share a common worldview, a certain canvas of memes. Claiming to rebuild nations on the sole basis of property right (and the contractual adherence to some values) simply becomes a modality of cosmopolitanism.

For an introduction to the theory of pecking orders, one may consult Robert Ardrey’s The Social Contract:

“In 1920 the British amateur ornithologist Eliot Howard presented the natural sciences with the concept of territory in animal affairs. In 1922, just two years later, a Norwegian scientist, T. Schjelderup-Ebbe, published in Germany his study of the social psychology of the chicken yard. It centered on his discovery of the pecking order in a flock of hens. From alpha to omega there is a rank order of dominance within the flock, and each hen has the right to peck those below it in the order, while none has the right to peck back. Thus alpha has the right to peck all, whereas none can peck her. And omega, of course, the last in line, gets pecked by everybody and can peck back at none. In just two years the twin principles of territory and dominance, the concepts at present most absorbing for students of animal behavior, came into being. Howard, despite his study of innumerable bird species, was conservative in confining his conclusions to bird life, the world he knew. Like Howard, Schjelderup-Ebbe went on to study sparrows, pheasants, ducks and geese, cockatoos, parrots, canaries. He was anything, however, but conservative. ‘Despotism,’ he wrote, ‘is the basic idea of the world, indissolubly bound up with all life and existence.’ He went beyond life: ‘There is nothing that does not have a despot… The storm is despot over the water; the lightning over the rock; water over the stone it dissolves.’ He even recalled a proverb that God is despot over the Devil.”

For an introduction to meme theory, it is worth quoting our friend Howard Bloom:

“As genes are to the individual organism, so memes are to the social organism, or superorganism, pulling together millions of individu¬als into a collective creature of awesome size. Memes stretch their tendrils through the fabric of each human brain, driving us to coagulate in the cooperative masses of family, tribe and nation… History, either natural or human, has never been the sole province of the selfish individual, essentially preoccupied with preserving his genes. For history is the playfield of the superorganism – and of its recent step-child, the meme.”

Although it is concerned with the coercive preservation of biocultural identity (and the coercive discrimination of immigration), the Hoppean version of anarcho-capitalism remains a modality of cosmopolitanism. The Hoppean covenant (which, anyway, is wholly chimerical, unrealistic) is nothing other than an intended substitute for the nation.

As for the argument that free immigration is incompatible as much with an anarcho-capitalist “covenant” as with the state’s respect for intranational property rights, that argument comes more as a rhetorical trick, a “derivation,” than as a rigorous, factual reflection. It implicitly assumes, indeed, that a nation and an anarcho-capitalist order both constitute – necessarily – a coownership (or a club), in which the decision to authorize (or refuse) the entry of someone is made by the coalesced owners (or the gathered members of the club). Yet that is a false conception as much of the anarcho-capitalist order as of the national edifice. The former is not more necessarily a club than it is necessarily a coownership. In other words, an anarcho-capitalist order organized as a coownership (or as a club) only comes as a certain kind of organization for an anarcho-capitalist order.

As for the nation, it can in no way be a club or a coownership – in view of the juridical hierarchy necessarily present within it and the necessarily coercive character of the state (even democratic). On the basis of such a premise (i.e., that a nation or an anarcho-capitalist order necessarily comes as a coownership), one could just as easily argue that free trade necessarily violates property rights as much in a nation as in an anarcho-capitalist order – and that a policy opening up the nation’s frontiers to goods necessarily denies the right of the owners to decree which goods are allowed or not to cross the boundaries of their respective properties.

Free immigration and free trade must be limited – not in the name of a properly understood anarcho-capitalism, but in the name of the rejection of the relative cosmopolitanism that is inherent in classical liberalism and exacerbated in all varieties of anarcho-capitalism. Liberalism must be counterbalanced, limited by civilizational and geopolitical considerations.

In this respect, it is worthwhile recalling that the expansion of cosmopolitanism into Western nations only comes as the culmination of a process of subversion of Western civilization which began with the abandonment of the Indo-European order, i.e., the warlike and sacerdotal order – and with the advent of the bourgeois industrious society. Classical liberalism is engaged in the march of cosmopolitanism, in the sense that it has been leading the march towards free trade and free immigration. For its part, the national-liberalism of 1789 has been involved in the march of the bourgeois industrious society – with neither classical liberalism nor anarcho-capitalism coming to oppose intellectually the bourgeois society and to take up the defense of Indo-European tradition. Quite the contrary.

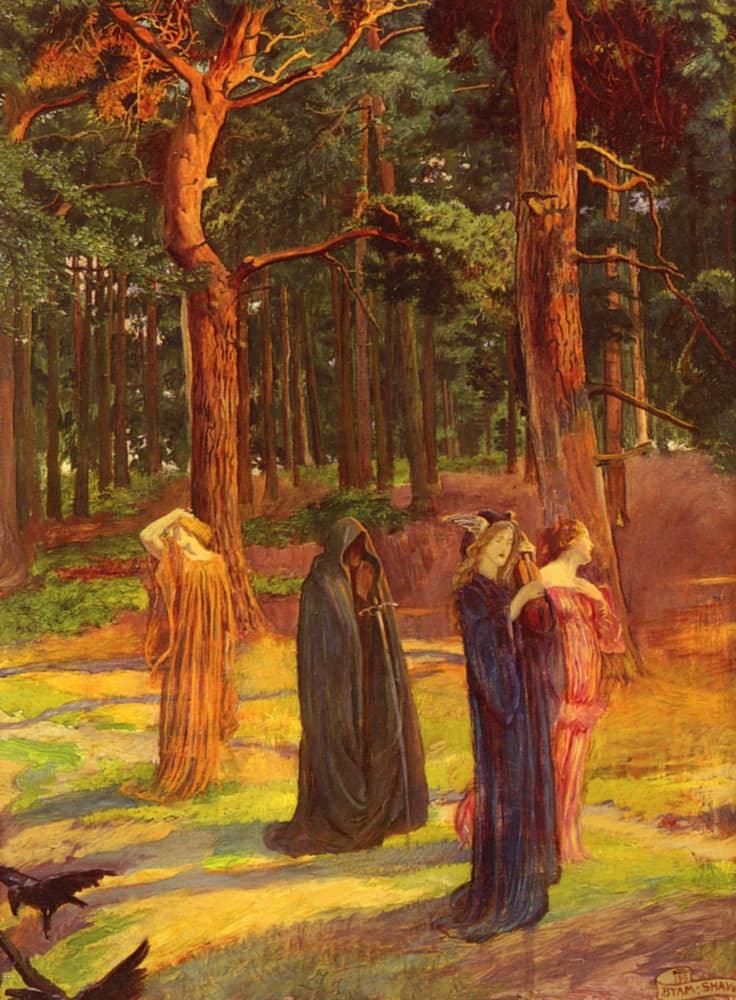

The National-Liberalism Of 1789 In The Face Of Indo-European Tradition

The Indo-European tradition is one that is both organizational and axiological. Organizationally, it comes as the tradition of a tripartite and hierarchical organization of society, in which the sacerdotal caste (for instance, the druids in Celtic society, the brahmins in Vedic society, and the magi in Persian society) takes precedence – spiritually – over the warlike caste; and in which both the warlike and sacerdotal castes take precedence – juridically – over the productive caste. The authority to decide on spiritual and otherworldly issues is up to the priests (and only up to them), who notably serve as magicians and esotericists.

As for political power (i.e., the power of command and decision, as well as the authority to decide on secular issues), it always lies with the warlike caste (which can share it, more or less, with the sacerdotal caste, depending on the considered society). For their part, merchants, peasants, and workers find themselves subservient – through their inferior position in the tiering of juridical ranks – to the warlike and sacerdotal castes.

Axiologically, the Indo-European tradition comes as that of an ethos which may be called individualist-warlike (or aristocratic-warlike, or quite simply aristocratic). That ethos consists (for a given aristocrat, i.e., a given member of the hegemonic warlike caste) of undertaking to singularize oneself through the exercise of military domination (with regard to the productive caste’s members); and through the pursuit of eternal glory on the battlefield, i.e., the pursuit of military exploits, occasioning eternal remembrance of one’s name and one’s fame.

The juridical enfeoffment of the productive, industrious caste to the magus and the warrior is traditionally accompanied with a twin primacy of sacerdotal and aristocratic values, i.e., magic (including esotericism) and warlike individualism (as defined above).

The national liberalism of 1789 set up a reversal of the Indo-European tradition by placing the productive function at the top – both from an axiological and organizational point of view. Thus followed the marginalization of sacerdotal and individualist-warlike values (but not of war itself); the disappearance of intermediate juridical inequalities (but not of the state as such); and the triumph of what may be called the bourgeois materialist spirit. As concerns war, the overthrow of the Indo-European triad (for the benefit of economy) meant, not the decrease of war itself, but actually the necessary marginalization of the warlike-individualist ethos, which is by necessity the contempt of the warlike-aristocratic ethos (and therefore for the aristocrat himself).

While a bourgeois nation does not necessarily ignore the practice of war, it is necessarily prey to the replacement of the Indo-European warlike-individualist ethos (i.e., the ethos of rendering oneself glorious and immortal through military exploit) with what may be called the warlike-sacrificial ethos, i.e., the ethos of anonymizing oneself within the mass of soldiers, dead for the Motherland.

Besides, far from encouraging the global outburst of human instincts, the hegemony of economy thwarts the spontaneous, natural aspirations of those instincts that are territory and identity, domination and adventure – and requires the forced hypertrophy of the economic instinct, i.e., the instinct which leads us to seize peaceful opportunities of trade and production. Such hypertrophy goes against the spontaneous, natural hierarchy of man’s instinctual needs. To humans, identity and territory, adventure and domination, matter – naturally – more than material enjoyment and economic cooperation.

Nowadays, the defense of “warlike heroism” is most often accompanied by a sacrificial conception of the heroic ideal. The “hero” is indeed perceived as the one who is ready to die for society (the nation, the fatherland, the Republic) and who forgets, or denies his individuality, standing aloof from any selfishness in his conduct. This conception, which is celebrated as much in bourgeois democracies as in totalitarian regimes, diverges completely from the idea that pagans had of heroism in the ancient world. Far from sacrificing himself for society, the hero, the aristocrat, established the ruling caste (which could be interpenetrated with the sacerdotal caste). In a sense, the society was sacrificed for the benefit of the hero, in that social organization was designed for the benefit of the warlike and sacerdotal castes, the latter living off the work of slaves and the productive caste’s efforts.

Besides, war was valued, and perceived, not as a way of self-denial but quite the contrary, as a way of supernatural fulfillment of an individual. In other words, a way for him to render himself divine (or to reveal, confirm his divinity), and to have his exploits sung forever by other people. The clairvoyance (i.e., ability for divination) and sorcery of the priest were regarded as another modality of the supernatural fulfillment, i.e., another mode of deification for an individual.

But, what may be called bourgeois materialism, won the spirits, as bourgeois nationalism was extending its grip over the Western world. The bourgeois materialist state of mind can be negatively defined as a state of mind mocking and refusing the warlike-individualist spirit, and denying the reality of magic and that of clairvoyance – as well as the reality of supernatural fulfillment. It can be positively defined as a state of mind reducing the world to its material aspects and putting above everything else – including above the pursuit of (military, intellectual, artistic, technological, or even economic) exploits – the pursuit of material subsistence – more precisely, the pursuit of reciprocal material subsistence among peaceful, formally equal proprietors.

Not content with rejecting (intermediate) inequalities of law, and advocating the reduction of inequalities to the income, diploma, and occupation inequalities under the aegis of the state, the national-liberalism of 1789 advocates a materialist and sacrificial conception of human existence, in that the individual must renounce an heroic life (i.e., a life primarily dedicated to the pursuit of singularizing, immortalizing exploit – even at the expense of his subsistence), and devote himself only to enrichment, as much his own as that of the nation, while proving ready to sacrifice his life for the nation from time to time. More precisely, the individual is, on the one hand, allowed (and even encouraged) to satisfy peacefully his “personal interest” at the economic level – with the well-understood economic interest of individuals coinciding allegedly with “the interest of the nation” – but on the other hand, expected to be ready to set his life at stake at a military level – and to sacrifice himself for his motherland.

While war in a traditional Indo-European society is either the work of the warlike nobility and its mercenaries, or the work of a conscript army that respects and incorporates within it the status divisions, conscription comes as a necessary trait of the bourgeois nation. As the bourgeoisie dethrones the sacerdotal and warlike castes, and rank inequalities dissipate (for the benefit of the sole economic inequalities), war becomes the business of all.

On the same token, the heroic ideal, i.e., the ideal of supernatural self-affirmation through war or through the practice of magic, is dismissed (or marginalized); and it is expected from war that it will be henceforth a path exclusively (or semi-exclusively) of self-denial – the path of self-sacrifice “in the interest of the nation.” It is worth noting that the bourgeois nationalism of 1789 thus counterbalances the materialist bourgeois mindset (which is perfectly hostile to the compromising of one’s material subsistence, whether it be compromised for warlike-individualist motives or for sacrificial motives) with a spirit of self-sacrifice for the national deity – the latter being admittedly an earthly, gynecocratic deity.

The mediocrity of classical liberalism, as seen above, notably lies in its pacifism. The mediocrity of the national-liberalism of 1789, which has nothing to do with pacifism, notably lies in its sacrificial conception of heroism. The transition from a warlike and sacerdotal order, such as the France of the Old Regime, to a bourgeois order does not mean that bellicosity necessarily dissipates; but that the warlike and sacerdotal castes are necessarily dissolved and the state necessarily falls into the hands of the bourgeoisie.

It also means that the warlike function – if it does not disappear – is necessarily and only put at the service of the productive function, i.e., used to keep the economy operating – or put at the service of the promotion of the nation’s founding ideals, i.e., used to impose those ideals upon the world. In other words, war ceases to be practiced for the purpose of the individual’s supernatural fulfillment, so that “warlike heroism” is henceforth understood and praised in sacrificial terms; and so that the chivalrous, warlike-individualist spirit of the warlike aristocracy is jointly abandoned for the benefit of the bourgeoisie’s materialistic spirit and for the benefit of the motherland’s sacrificial cult.

In the framework of the transition from warlike-sacerdotal France to bourgeois France, the Napoleonic wars were prey to contrary forces. On the one hand, they occasioned an ultimate resurgence of the warlike-individualist culture of traditional France – as noted and praised by Nietzsche while on the other hand, they enshrined the bourgeois industrious order and the abandonment of the warlike-individualist ethos, for the benefit of an all-encompassing pursuit of material subsistence, counterbalanced by occasional self-sacrifice for the Nation.

In The Nomos of the Earth, Carl Schmitt rightly noticed that the Jacobins “decried the classic interstate war, purely military, of the 18th century as a cabinet war of the Old Regime and… rejected as a matter of tyrants and despots the liquidation of the civil war and the limitation of the external war accomplished by the state. They replaced the purely state war with the people’s war and the democratic mass uprising.”

The national-liberalism of 1789 is therefore a nationalism which breaks with the Indo-European tradition; and that subverts the traditional hierarchy in values and in juridical ranks. More precisely, it combines the ideal of free enterprise and of an extended division of labor with the ideal of a bourgeois nation. In other words, a nation in which juridical, professional, economical, and academic inequalities have such nature that the bourgeois class (i.e., the “merchants” in the broad sense: entrepreneurs, capitalists, executives, consultants, bankers) is henceforth the politically dominant class; and in which the bourgeoisie’s materialist state of mind and the moralism (i.e., the contempt for the cultivation of supernatural, virile values), constitutive of such a mind, henceforth serve as reference values. Here, Vilfredo Pareto proposed the phrase “virtuism.”

talian Futurism, which culminated in Fascism, was certainly revolted against bourgeois society and its materialist, virtuist spirit: “We want to demolish museums and libraries, fight moralism, feminism, and all opportunist and utilitarian cowardice,” wrote Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. To the extent that Soviet nationalism strictly subordinates the warlike function to the productive function, i.e., reduces war to a sacrificial instrument for keeping the economy operating (in addition to serving the territorial expansion of the memes of Marxism-Leninism), nationalist socialism lies in the lineage of the nationalist liberalism of 1789. It combines the ideal of the collective ownership of the means of production, and of central planning, with the ideal of a proletarian nation, i.e., a nation in which it is the proletarian’s materialist state of mind which axiologically prevails, and in which the ruling class is exclusively composed, if not of proletarians, at least of intellectuals, claiming to rule in the name of proletarians. (It is worth noting that, in practice, the Stalinian regime believed in magic and solicited the gifts of magicians – in contradiction to the materialism of its foundational Marxist-Leninist ideology).

As for Hitlerian nationalism and Fascist nationalism, they were certainly socialist nationalisms linked to proletarian nations; but their socialist nationalism was traversed by contrary forces with regard to the warlike function. On the one hand, they witnessed resurgence of the Indo-European warlike-individualist spirit – as exemplified in the following lines of Mario Carli’s Fascismo Intransigente. “The warlike spirit [warlike-individualist spirit] is the fundamental character of the Italians; it is not a fascist invention nor a post-bellum attitude. Find me a single moment in history in which we have not fought – it doesn’t matter for whom or for what… It took a century of democratic dysentery to drown the individual worth of Italians in egalitarian and humanitarian soup. But today, it is making its return… Mussolini, Minister of War! That is what seems to me the supreme and most splendid embodiment of the Mussolinian spirit!”

On the other hand, that resurgence of the Indo-European warlike-individualist spirit was counterbalanced with the implementation of a sacrificial, gynecocratic approach to war – expecting the individual to be ready to anonymize himself within a mass of faceless soldiers, compromising their subsistence for the sake of the nation’s economic interests, or for the sake of its ideological interests (i.e., the expansionist pretensions of the nation’s foundational memes).

As such the socialism of Nazi Germany as the socialism of Mussolinian Italy were therefore, in part, a socialism of the rupture with the Indo-European tradition. In the case of Nazi Germany, the subordination of the warlike function to the productive function was described in these terms by Ernst Jünger, in The Worker. “The armed defense of the country is no longer the obligation and the privilege of the sole professional soldiers; it becomes the task of all those who are likely to bear arms… On the same token, the image of the war, which represents it as an armed action, is blurred more and more in favor of the much broader representation which conceives of it as a gigantic process of work. In addition to the armies fighting on the battlefield, new kinds of armies are emerging: the army in charge of communications, the one responsible for the supply, the one that supports the equipment industry – the army of labor in general.”

Further Qualifications Of Heroism And Bourgeois Society

With regard to the precise symptoms of the productive function’s hegemony in contemporary Western society, it has been commonly argued that such hegemony implied the predominance of the “utilitarian” lifestyle associated with the merchant; and the dissipation of the “heroic” way of life associated with the warrior.

To begin, the distinction between the hero (seen as the one who is ready to die for others) and the merchant (seen as selfish and calculating), developed by Werner Sombart, does not stand up to scrutiny. The hero in the traditional sense is the one who performs military exploits, i.e., exceptional deeds on the battlefield, singling him out and endowing himself with eternal fame, and who manages – through self-mastery and inner harmony – to properly, intensively satisfy his territorial and adventurous, identity-minded and domineering instinctual drives.

Only the hero in the modern sense, the hero as defined in bourgeois nations, is the one who dies for others. Achilles is ready to die, but for the singularization of his existence and the immortalization of his name. Whether in fiction or in History, many Indo-European heroes have been merchants, the emblematic example remaining to this day, being Cosmo de Medici – the noble who rose to the top of Florence by virtue of his skill in finance and founded a dynasty of Tuscan rulers. (It goes without saying that when we defend heroism in the traditional, pagan sense, we do not intend, nonetheless, to castigate the sacrificial acts of generosity in society – including the devotion of the saint and that of the mother. We only intend to distinguish between what is specifically heroic and what is sacrificial).

At first sight, it may seem paradoxical to denounce the virtuism of the bourgeoisie, while celebrating the warlike-individualist spirit of the great captains of industry. In fact, the “bourgeois” who applies a chivalrous code (i.e., a warlike-individualist code) in business is bourgeois only at an economic level. Morally and psychologically, he is instead a warrior, a kshatriya, a knight. The soap opera, The Young and The Restless, very popular in France, features a businessman, Victor Newman, cultivating a warlike-individualist, Nietzschean morality, in the puritanical and sententious environment of Protestant America. It cannot be denied that the “will to power,” when understood as the simple fact of aspiring to hegemony in society, is common to bourgeois, proletarians, warriors, and magicians. Friedrich Nietzsche points to that when he – rightly – writes that “the oppressed, the lowly, the great masses of slaves and semi-slaves desire power.”

On the other hand, the “will to power,” when understood as the fact of aspiring (and being able) to harmonize the inner chaos of instincts and to display courage (before the risk of death) and high, flexible intelligence (in military tactic and in seduction) is unique to aristocrats and magicians – and to those of “bourgeois” who have an individualist-warlike soul. Not less rightly, Nietzsche deplores that “one stigmatizes with the most insulting names the great virtuoso of life (whose sovereignty of oneself constitutes the most marked contrast with the vicious and the debauchee). Even today it is thought necessary to disapprove a Caesar Borgia – that is laughable. The Church excommunicated German emperors because of their vices, as if any monk or priest could afford to discuss all that a Frederick II has the right to demand of himself. A Don Juan is sent to hell – it is naive. Has one noticed that all the interesting men are missing in Heaven?”

The hegemony of merchants in contemporary Western society necessarily means the hegemony of a class whose will to power cannot be denied when taken in its first sense; but who lack manliness, courage, temperance, and a creative, independent mindset – in short, the will to power taken in its second sense.

In a fundamentally industrious society, the primacy of economy over war (what is constitutive of such type of society) does not necessarily imply that a strictly utilitarian way of life (i.e., unconcerned as much with the concern for meditating on the mystery of existence as with the idea of dying for someone or something) predominates. That primacy does not necessarily imply, either, that the instincts of homo sapiens are unleashed – and that man regresses to the “animal stage.”

When the productive function becomes predominant, it necessarily follows that a way of life impervious to the warlike-individualist ethos (i.e., the ethos of rendering oneself glorious and eternal through the execution of exploits – and compromising one’s material subsistence in the name of immortality) becomes predominant. It does not necessary follow that a way of life strictly utilitarian becomes predominant – and that the practice of war or meditation on Heideggerian Being disappears (or gets marginalized).

Besides, the economic instinct (i.e., the instinct that leads us to seize peaceful opportunities of trade and of production) is, indeed, necessarily solicited as the productive function, and which becomes hegemonic; but it is then solicited against the natural prevalence of our aggressive (i.e., territorial and domineering, adventurous and identity-minded) instincts. Hence it is a properly counter-instinctual way of life which is finally solicited – the human animal privileging spontaneously, instinctually, naturally the satisfaction of his aggressive instinctual inclinations (for dominance and territory, identity and adventure) rather than the satisfaction of his instinctual inclination for economic cooperation. Those are the true necessary symptoms of the hegemony necessarily acquired by the productive function in a fundamentally industrious society.

It is to the anthropologist and philosopher Robert Ardrey that we owe the remarkable elucidation of man’s priority, his instinctual needs: territory and domination, but also identity (i.e., knowing and proving who we are, experimenting with, and seeing recognized, the uniqueness of our personality) and adventure (i.e., leading an exhilarating, meaningful life). It is true that those aggressive instincts very largely dictate our consumption choices – for the good reason that in the enjoyment of material goods itself, aggressiveness (i.e., the concern for identity, territory, domination, and adventure) naturally matters more than material subsistence (i.e., housing, clothing, food, health, financial security).

It is true that Promethean growth (i.e., based on the domestication of nature through coal and nuclear industries) and modern capitalism (i.e., capitalism of the entrepreneurial, financialized, digitized, and globalized type) have allowed consumer goods to satisfy the aggressiveness of the masses as never before. Let us think of the social status afforded by the possession of an iPhone alone, or of a luxury watch; or the adventure offered by an opus of the video-game saga, The Legend of Zelda. The fact still remains that as such, economic life – and a fortiori consumption – can only, in an imperfect, diverted manner, satisfy the aggressive instincts of man; and that those instincts (i.e., territory and domination, adventure and identity) actually are thwarted, not fulfilled, as economy becomes ascendant in the scale of values.

Besides, the hegemony of the productive function with regard to war does not only imply that on the battlefield, the warlike-individualist ethos (which does not fail to surface occasionally among soldiers) is scorned. The primacy of economy implies that the warlike-individualist ethos is despised in the realm of war, literally; but also in the field of economics, and in these softened and derivative forms of war that are entrepreneurial or financial competition (not to mention intellectual, cognitive competition).

A society that has become completely hostile to heroism does not praise more the business kshatriya than it admires and protects the John Rambo-style soldier, i.e., those of soldier who lives according to a warlike-individualist ethos. From the soldier, such society expects that he be ready to die for the homeland (instead of pursuing immortalizing exploit and looking for the thrill of blood and adventure); and from the entrepreneur, that he simply make profits (instead of “dreaming” himself as heir to Alexander the Great).

The social contempt for military, economic, and intellectual heroism necessarily characterizes the productive function’s hegemony; and that contempt culminates in the importance taken by diplomas in contemporary Western society. The culture of the diploma indeed ensures the access of devirilized individuals to key positions in companies, governments, universities, and armies. Basically, the culture of the diploma has enshrined the spiritual and moral hegemony of the vaishya over the kshatriya and the brahmin.

Some people welcome the decline in violence that – despite the Terror and the Great War – accompanied the rise of the bourgeoisie and the break with the Indo-European tradition. The pacification of Western society would be a marvelous gift of the bourgeoisie to the world. Yet the consubstantial violence of traditional Indo-European societies was a sign of their virility – the sign that the circulation of warlike elites was ongoing and that the military struggle for social, juridical preeminence was doing well. The gradual pacification of the white world after coming out of the Renaissance should not be interpreted as progress in every respect. The decline in intra-Western violence necessarily implies the decline in the virility of the world’s elites – as it necessarily implies the pullback of those traditional ways of ascent that are war and the Florentine virtù. It necessarily implies the prevalence of the diploma and entrepreneurship among the processes of selection of elites. As the circulation of elites is pacified, the selected elites emerge more and more emasculated and less and less heroic – to our greatest misfortune before the invaders from Africa and the Middle East. When it is not simply humanitarian cowardice that motivates the elites of Western nations to let terrorists and non-indigenous settlers prosper with impunity on Western soil, they behave as emissaries of the world superclass: for which the “great replacement” of the Western man is a clearly established goal.

Towards A New National-Liberalism: Territorial-Aristocratic Liberalism

But can one conceive a nationalism that combines the ideal of free enterprise and of an extended division of labor with the warlike-sacerdotal order on which Tradition is built? We will try to show that, yes, such a nationalism is conceivable; and we will outline the contours of that radically new doctrine.

But first, we must specify that we must use the distinction of Julius Evola, that of between an aristocratic nationalism (based on the warlike-sacerdotal aristocracy and on a heroic, supernatural conception of existence) and a plebeian nationalism (based on equality and materialism). Within national-liberalism, we believe that the same distinction shows itself, between a national-liberalism of the plebeian kind (that of the French Revolution), and a national-liberalism of the aristocratic kind – the one we defend and which is biding its time. The common category of national-socialism allows subsuming Stalinian and Maoist nationalisms as well as Hitlerian and Mussolinian nationalisms – and national-socialism itself only comes as a modality of plebeian nationalism.

In its new, aristocratic version, national-liberalism approves the prosperity and the “recognition” of merchants, while rejecting their juridico-political and moral hegemony. It rejects the enfeoffment of the warlike function to the productive and reproductive function; and intends to restore the twin primacy of warlike and sacerdotal values in society, as well as the juridical hegemony of magicians and warriors. In addition, it defends property right and modern capitalism, i.e., capitalism of the entrepreneurial, globalized, financialized, and “digitized” kind. It intends to preserve the organizational and axiological features of Indo-European tradition in the context of modern capitalism.

Such nationalism rejects any type of egalitarianism – including the universality of law, which serves, let us recall, as the fundamental value of liberalism. To the extent that such nationalism affirms its attachment to free enterprise and the extended division of labor, and recognizes the true value of the coordinating role of the entrepreneur (who adjusts the division of labor in an optimal direction in view of people’s expectations, in terms of consumption and investment), it is all the same allowed to regard that doctrine as a modality of liberalism – a borderline case of liberalism.

Since this version of liberalism defends the nation, therefore the natural, spontaneous aspiration of our territorial instinct, and defends the juridical, moral hierarchy constitutive of Indo-European tradition, therefore the warrior-sacerdotal aristocracy and the spontaneous, natural aspirations of our domineering, adventurous, and identity-minded instincts, it is permissible to baptize that doctrine, as “territorial-aristocratic liberalism.” It may also be called a “territorial, aristocratic monarchy,” embracing some of the liberal values – those retained values, i.e., private property, free enterprise, and the extended division of labor, finding themselves counterbalanced with the twin primacy of vales that are sacerdotal (i.e., magic and esotericism) and warlike-individualist (i.e., the pursuit of eternal, individual glory on the battlefield at the expense of material subsistence).

While the national-liberalism of 1789 combines the ideal of free enterprise with the rejection of intermediate castes (between the state and the individual), and with a materialistic, egalitarian conception of human existence (i.e., a conception which rejects the supernatural ends and that jointly devalues the magus and the warrior for the benefit of the merchant), territorial-aristocratic liberalism simultaneously preaches free enterprise and the return to Indo-European intermediate castes and to the Indo-European system of values. Far from denying race, the national-liberalism of 1789 recognizes the bonds of blood on which the nation is built.

More precisely, it rejects the distinctions of rank within the nation – and thus rejects caste consciousness for the benefit of mere race consciousness. That state of mind culminates into the “racism” of 1789 towards warlike nobility, who sees itself conveniently likened to a foreign race. For its part, territorial-aristocratic liberalism advocates race consciousness, but also caste consciousness and the restoration of sacerdotal, warlike nobility. Nevertheless, it remains attached – like the national-liberalism of 1789 – to free enterprise and the extended division of labor. Besides, it denounces hard ecologism and promotes Promethean growth, i.e., the kind of growth that does not rest on the extension of the division of labor, but on the emancipation of human productive powers (through the exploitation of fossil, nuclear energies) with respect to the cycles of nature.

Man, as territorial-aristocratic liberalism envisions him, is not that puppet of the theory of a David Hume, a John Locke, or a Murray Rothbard, who strictly pursues his private interest (what, in their theoretical framework, insidiously boils down to the requirements of material subsistence), while deliberately and calmly cooperating with others in the framework of an extended social division of labor, protected by universal rules of law.

But man, as territorial-aristocratic liberalism envisions him, is fundamentally aggressive. First and foremost, he is territorial and domineering, adventurous and identity-minded, rather than concerned with his comfort and his material subsistence. Besides, this new liberalism sees man, not as a rational agent whose determination of goals – and whose choice (and use) of means – are deliberate at every moment, but as an agent most often acting (i.e., determining goals and choosing and using means) under the effect of uncontrolled impulsions with an emotional, “residual” origin – and only giving a deceptive appearance of rationality to his actions through “derivations.”

Territorial-aristocratic liberalism nonetheless envisions (and praises) the magician, the aristocrat, and the warlike-individualist entrepreneurial type as those minority anthropological types actually capable of rationality and self-mastery. It accordingly subscribes to Éliphas Lévi’s statement that “free men are to rule the slaves, and the slaves are called to liberate themselves; not of the government of free men, but of that servitude of brutal passions, which condemns them not to exist without masters.”

Therefore, territorial-aristocratic liberalism cannot hold society for that “spontaneous order” dear to Friedrich A. von Hayek. That murky expression actually refers to a materialist, juridically egalitarian order, in which the struggle for the juridical rank is eclipsed for the benefit of sole economic, academic competition, and in which the aristocratic cultivation of a warlike-individualist ethos is eclipsed for the benefit of the bourgeois prioritizing of material subsistence – and the bourgeois mocking of supernatural values.

Society, as envisaged by the new liberalism, is necessarily organized around a pecking order, a hierarchy of castes (be it a hierarchy which ignores the intermediate ranks), and never around universal rules of law. But while rejecting formal egalitarianism, i.e., the universality of the rules of law, territorial-aristocratic liberalism does not accept castes without social mobility, i.e., without a system of competition for status. Besides, it intends to preserve the identity of the peoples, as it does not forget that a relative genetic and cultural homogeneity, as well as a common territory, are an integral part of the social link, and that one cannot boil down everything to the division of labor and commerce.

If so many anarcho-capitalists indulge in “multiculturalism,” it seems that it is due to the fact that conversely, they represent to themselves the division of labor as the cement of society – and that they consider that genetic and cultural proximity plays a secondary, or even insignificant, role in socialization processes. Besides, they deny the territorial instinct. They therefore imagine that all sorts of heterogeneous races and cultures can cohabit peacefully within the division of labor established on a given space.

Let us talk about the state. Its vocation in territorial-aristocratic liberalism is not to guarantee an egalitarian right (i.e., universal freedom), nor is it to administer economy or to redistribute incomes. The state, as territorial-aristocratic liberalism deems it, comes as the guardian of a hierarchy of castes nonetheless opened to social mobility. That hierarchy subordinates (on a juridico-political level) merchants to warriors and magi, while warriors and the political sovereign (unless he himself stems from the sacerdotal caste) are spiritually subordinated to the magi.

Thus, the state brings form and harmony, “a differentiated and hierarchical order of dignities” (according to the formula of Julius Evola), to a preexisting multitude, who proves relatively homogeneous at a genetic and cultural level. Thus, too, the state puts into practice the two laws (dear to Robert Ardrey) that life in society renders necessary in all vertebrate species, namely, the inequality of socio-juridical statuses (for the benefit of the juridico-political domination of the “alphas” that are warriors and magicians), and the opened competition for status – instead of an automatically hereditary perpetuation of socio-juridical ranks.

Further, territorial-aristocratic liberalism is fully open to consumerism and technological innovations. It envisions the cosmos as an active entity, striving relentlessly towards order and complexity – and the human being as a catalyst for cosmic creation. It believes that the cosmos mandates man to perpetuate and multiply the creative gesture of nature – notably through the accumulation of capital and through the cheap provision of qualitatively new goods and services for the masses. (On that point, it is worth specifying that territorial-aristocratic liberalism positively assesses the influence of Judaism on the Indo-European mind. More precisely, the influence of the Judaic conceptions of time as linear; the state authority as profane; and man as jointly expected to prolong the divine creation and to subdue to the legal, natural order that Yahweh established. We will come back to that subject elsewhere).

Territorial-aristocratic liberalism considers that a nation can prove both “consumerist” (in the sense that it pursues the enjoyment of consumer goods) and faithful to Indo-European tradition – i.e., as cultivator of virile, supernatural values, while maintaining the connection with the spiritual realm. As it defends traditional, pagan heroism (against the parody that is sacrificial “heroism”), it also envisions heroism as a contingent attribute of the productive function – and not only as a necessary attribute of the warlike function. It believes that it may from time to time bring forth an entrepreneur who possesses a warrior-individualist spirit. Not content with praising the men who build a commercial or financial empire, it promotes the enthronement of the great samurais of finance and the great captains of industry among the ranks of the warlike ruling caste.

Further Qualifications Of Territorial-Aristocratic Liberalism

In the end, our liberalism is archeofuturist, in the sense that it conciliates warlike society and consumer society, with hegemony of the magus and prosperity of the merchant. With the overthrow of the Indo-European triad, the magus has lost his spiritual authority for the benefit of the bourgeois. The moral authority henceforth lies with the bourgeoisie, who seek professional advice from the magus, i.e., solicits his gifts of clairvoyance for the smooth running of business.

Our liberalism, which re-engages with the spiritual, suprasensible order and breaks with bourgeois materialism, is a liberalism of the Indo-European tradition. It intends to restore the traditional juridico-political order, which enshrines the spiritual primacy of the magus over the warrior and the producer – and sets up the juridical primacy of the magus and the warrior over the producer.

Our liberalism also prohibits itself from intervening in the choices of individuals with regard to pensions and health care, with the sole exception of exceptional prophylactic measures to be taken in the case of a serious pandemic. Besides, it believes that education must respond to warlike and aristocratic values.

Some additional clarifications deserve to be brought out about globalization. The inequalities of law associated with society prior to 1789 amounted to exceptional laws for the benefit of the warlike and sacerdotal nobility, which existed within nations and sustained links of solidarity beyond nations. The contemporary inequalities of law amount to exceptional laws for the benefit of the bourgeoisie (who has taken control of governments through the dissipation of intermediate rank inequalities); but also, for the benefit of a small number of companies and banks, whose executives compose what has been judiciously called a world superclass, i.e., a class that sits above the nations.

It would be wrong, however, to conceive of those inequalities of law (for the benefit of the world superclass) as consubstantial with the phenomenon of globalization. The grip of the world superclass comes as an accidental feature of the globalization as we live it – and not its necessary visage. Territorial-aristocratic liberalism intends to restore the traditional inequalities of law and to couple them to globalization. It is not a question of restoring those inequalities against globalization.

Quite often, the denunciation of “globalism” and of the “reign of merchants” proceeds from the vilest petit-bourgeois resentment. Behind the moralizing speeches against Starbucks, KFC, Volkswagen, Sony, Amazon, or Apple, one can guess the second-class entrepreneur, jealous of the power of multinationals. Multinationals actually do represent a danger – for the nation’s biocultural preservation – so long as they behave as agents of influence for cosmopolitanism. But they are by no means harmful (from that angle) in the cold pursuit of their economic interests. It is sound, and even imperative, to counter the cosmopolitan lobbying of multinationals. It is insane to denounce the strategy of multinationals to apportion activities on a global scale.

Specializing the regions of the world according to the comparative advantages does not harm, but benefits, the prosperity of nations. Far from deploring the power of multinationals, territorial-aristocratic liberalism knows that the power of a nation implies a hegemony that is economic not less than military and cultural. It is hardy outrageous that the firms, an ambitious nation gives birth to, conquer an international market, implement subsidiaries around the world, and grant favors from foreign governments.

Concerning protectionism, territorial-aristocratic liberalism recognizes that the facilitation of trade between nations, which amounts to facilitating the extension of the division of labor (across borders), as well as the coordination of the division of labor (via the entrepreneurial reallocation of capital across borders), necessarily benefits consumers. It recognizes that the advantaged situation of the consumer means the mutual enrichment of nations engaged in free trade. Nevertheless, it knows that it is not true that such mutual enrichment implies that the gains of free trade are also mutual on a geopolitical level.

If openness to free trade allows the enterprises of a foreign nation to gain the upper hand over the enterprises of the nation adopting free trade, or the foreign labor force to replace the labor force of that same nation, then there is actually a balance of power which is established. Free trade is always a positive-sum game from the point of view of consumer enrichment; it is very often a zero-sum game from the point of view of the hegemony of the nation.

A wise government must seek the right balance between free trade and protectionism. It must ensure the enrichment of the consumer without losing sight of economic hegemony. It is quite legitimate to quote the wording of Voltaire. “To be a good patriot is to wish that one’s own community should enrich itself by trade and acquire power by arms; it is obvious that a country cannot profit but at the expense of another and that it cannot conquer without inflicting harm on other people.”

A word on currency. Applying the teachings of the Austrian School of Economics, territorial-aristocratic liberalism abstains from entrusting the monopoly of the issuance of money to a single organ, such as, the central bank in its present sense. It ensures the free competition and circulation of currencies in a strict concern for respect for property right. It can nonetheless entitle the state to ban the currencies disrespectful of private property, which unveil purchasing power, distort the production structure, and generate shortsighted behaviors. It can also entitle the state to approve the currencies allowed to circulate, without the state being entitled to intervene in the process of production, exchange, and circulation.

Territorial-aristocratic liberalism favors any currency likely to clarify in the mind of the nation that money – by reason of its character as a means of exchange and as a store of value – coordinates production, exchange, and the temporal preferences of individuals; and that it must obey, accordingly, a principle of relative rarity and of very high quality. The practice of the fractional reserve by the banking institutions will be prohibited. Banking regulations will be abolished to return to commercial law and to private law in the strictest respect for private property. Counterfeiting will be severely punished by law.

Finally, it is worth noting that our reform of liberalism joins a dual affirmation towards which the conception of socialism in Édouard Berth and Georges Sorel tended imperfectly – namely, the affirmation that the class struggle between bourgeois and proletarians, within the framework of entrepreneurial capitalism, instead of being overcome, must be preserved indefinitely (and ensure the regular sanitation of the bourgeois elite); and that the degree of kinship of the virtues required in economy and war, while it reaches a certain height in a certain relation to the labor of workers, is nevertheless brought to its pinnacle within the strict framework of a certain entrepreneurial practice. That in which, according to Sorel’s statement, come together “the indomitable energy, the audacity based upon an accurate appreciation of its strength, the cold calculation of interests, which are the qualities of great generals and great capitalists.”