Scholars and lay readers often assume that Italy joined Germany in 1940 because “the end of the war appeared to be on the horizon, Mussolini concluded the best choice was to join the Germans in their war against France and Britain, in order to seize territory in the Mediterranean. Malta, Corsica, Savoy and Nice – the Italian territories possessed by foreign powers – and Tunis; and along with other African lands, these were meant to compensate Italy for the the ‘disloyal behavior’ that London and Paris had exhibited in 1919.”

I had this opinion too, until by chance, in late 2009, I had to prepare a detailed paper on the Italian point of view about the French 1940 Armistice. I should mention that the subsequent paper I wrote on this topic achieved remarkable success when presented – in Paris at the Ecole militaire, on January 15, 2010. Later, I developed the idea into a book, which was published in 2014, in Italian.

Back in late fall 2009, in order to understand the French Armistice clearly, I began with the war itself, and with the plans – if any – made before the war. So, I began from secondary sources, mainly official publications, such as, the accounts of the Italian Alpine campaign of 1940, and the Italian military occupation of France, along with the addition of Galeazzo Ciano’s diary and some other sources. While collecting all the data, I found some things which clashed with the commonly held view, and which, when brought together, yielded a new perspective that should at least be revealed and discussed.

The problem of why Italy entered World War II was at that time, in 2009, still unclear. Traditional historiography tends to give Mussolini the simple desire to gain some territory at the lowest possible price; while other authors suppose that war was declared only because the Duce wanted to demonstrate that the Italian people were warriors. Both these major explanations are not so convincing, unless one is firmly believes that Mussolini was completely devoid of cold judgement and reason and was playing a sort of poker with the worst cards. Now, apart from any kind of consideration about Mussolini’s mental faculties, when gathering all the strands of the economic and political situation in Italy in 1939-40, the mosaic that results is very different than the one proposed till now by Italian and non-Italian historiography.

While it is certainly true that the person who decided the Italian involvement in war was Mussolini, the question we need to answer is: How did things appear to him? What was his – and the Italians’ – perception of the situation, which could be quite different from how matters actually stood. This question is never answered; or, at least, this question has never had a really satisfying answer, one which might allow us to understand why Mussolini took that fatal decision. The problem has certainly been discussed in Italy and outside Italy, in various ways – but nobody has to-date offered an explanation which might lead us beyond mere suggestion, or a bias, or a notion.

There is an astounding lack of documents from Mussolini about this question. There are many memoirs and journals by other people, but one must be very careful with these, because they were all published after the war, when their authors wanted above all to try to justify themselves to the people and to history. Ciano’s Diary, The diary written by Giuseppe Bottai, one of the smartest men of Fascism, appeared only after his five-year service with the French Foreign Legion in 1944-49.

There are also books and memoirs written by civil and military officers, sometimes top officers, but none offer anything substantial, other than an occasional detail. And, thus, the problem remains always unsolved: Why did Mussolini, who had no intention of going to war, suddenly decide to declare war in June 1940?

It is also clear that given the above caveats, one cannot pretend to demonstrate the truth. It is only possible to suggest an hypothesis, a tentative answer to the afore-mentioned questions; and it will up to the reader to decide whether the hypothesis can be accepted or not, fully or in part, or totally rejected.

When seeking to understand the reason why a certain decision was made, the only doable thing is to gather all the information about the man who took that decision. Then, one can see if, by chance, after having considered the facts, there is anything which may be helpful in finding an answer.

Therefore, what was Italy’s situation during this period, militarily speaking? Was Italy put under any kind of pressure? And if so, what kind of pressure, from where and by whom? Could Italy sustain a war, and, above all, a war as an ally of Germany? What outcome could Italy expect?

Now, in view of contemporary military, diplomatic anad economic documents, the answer appears to be quite complex, and most definitely surprising and very different from what is commonly supposed.

The first facts to consider are economic data, because money defines and determines what the military can do. Italy’s financial situation, in the Spring of 1940, was terrible. This is very well known by Italian economic historians, but is normally not taken into consideration by Italian military historians, and appears to be completely ignored by non-Italian military historians and by lay readers, whether Italian or not.

In fact, actual sources are really very few. Apart from the well-known (in Italy) book by General Carlo Favagrossa, Perché perdemmo la guerra (Why We Lost the War), published in 1946, and by the former Mussolini Finance minister, Felice Guarneri’s Battaglie economiche (Economic Battles), published in 1953), a scholar can only look at basic sources, such as, the figures given by the Central Institute of Statistics in Rome, the reports and official publications by the Ragioneria Generale dello Stato (State General Auditing Board) about the Italian budget, that is to say, Il bilancio dello Stato negli esercizi dal 1930-31 al 1941-42, and Il bilancio dello Stato negli esercizi finanziari dal 1942-43 al 1947-48, and the annual reports of the Governor of the Bank of Italy to the shareholders from 1939 to 1946.

Books too are quite few concerning this topic of Italy’s economic situation during the years under consideration. These books include, Giuseppe Mayer, Teoria economica delle spese militari (Economic Theory of Military Expenditure), published in 1961; Epicarmo Corbino, L’economia italiana dal 1861 al 1961 (The Italian Economy from 1861 to 1961), published in 1962; and Giuseppe Toniolo, La Banca d’Italia e l’economia di guerra (The Bank of Italy and the War Economy), published in 1989. The most recent, and perhaps the best work about this issue, is Luciano Luciani, L’economia e la finanza italiana nel secondo conflitto mondiale (Italian Economy and Finance in World War II), published in 2009.

The economy was not going well at all in the 1930s, and unemployment was common. Studies about this aspect are still rare and seldom published; and one is tempted to ask how much Fascist propaganda had the lingering effect to convince people that all worked well. Anyway, one can find something in Enrico Cernigol and Massimo Giovanetti, Ricordati degli uomini in mare (Reminiscences the Men in the Sea), published in 2005), which consists of interviews with survivors of submarine crews. When answering the question, why did they enlist, most of the answers are more or less “because of the lack of work in the Thirties.” Something similar is found in personal accounts or memoirs of people who did not have important positions at that time and who were interviewed; or this reason is indirectly admitted in some contemporary documents.

Wars in Ethiopia and Spain, and the short campaign in Albania, were a huge financial drain on the Kingdom of Italy. Since 1935, two thirds of the annual state expenditure had been on armed forces. Italy’s global expenditure rose from 33 billion liras in 1935–1936 to 60 billion in the fiscal year 1939 – 1940; and the deficit progressively and constantly grew from 13 billion liras in 1935–1936 to 28 billion in 1939 – 1940. And when considering the disagreggated data, we find that military expenditure, because of war, was solely responsible for the deficit.

There was also another problem. The Italian state’s income depended on only 28 percent taxation, and 72 percent on revenue. This meant that given the normal diminishing of commerce in the time of war, the state would never have been able to retain the 72 percent, and thus a consistent reduction of income had to be foreseen. At the same time, it was clear that if limited wars like those in Ethiopia and Spain had been so expensive, a World War against France and Britain would be harder, if not impossible, to sustain.

So, here we have the first fact that Mussolini was well aware of: The impossibility of managing a medium- or long-term war against great powers because of lack of money. And Mussolini knew this well, since minister Guarneri clearly warned him, and soon was forced to resign.

The second aspect to be considered is that of the Armed Forces; and this was strictly linked to the lack of money. If the State had no money, and Italy lacked raw materials to achieve a general rearmement, it was impossible to fill the need for ordnance and restock the depots emptied by the recent wars in Africa and in Europe. The standard interpretation concerning the state of the Italian Armed Forces in 1939 is that they possessed old equipment, useless in a modern war. This is a fallacy. Their equipment was as good as other European armed forces in 1939, except perhaps the Germans. The problem was that the Italian Armed Forces lacked sufficient equipment to carry out the operations with which they were tasked. They did not have enough vehicles, weapons and ammunitions. And they could not acquire the material it needed in sufficient quantities because Italy lacked an effective industrial system.

Comparative figures for war production of high-technological ordnance, such as, aircraft are quite revealing. For example, in 1939, Italy produced 1,750 aircraft; in 1940 3,250. The next year, 1941, marked the highest point of production with 3,503. Then, Italian production slowly decreased: 2,813 in 1942 and 1,930 in 1943, for a total of 13,523 planes throughout the entire conflict. In 1942, Japan made 9,300 planes, Soviet Union 8,000, Britain 23,671, United States 47,859 and Germany15,596. That is to say, in only one year, Germany produced more aircraft than Italy did in four years of war. German aircraft were faster, more effective, powerful and modern than Italian ones. During the period 1939-1945, Japan produced 64,800 aircraft, the Soviet Union 99,500, Germany 125,072, Britain 125,254 and United States more than 300,000. These figures have been officially published by the Italian Air Force in Rodolfo Gentile, Storia dell’Aeronautica dalle origini ai giorni nostri, (Florence, 1967), and in Vincenzo Lioy, Cinquantennio dell’Aviazione italiana, (Rome, 1959).

So, lack of money, weapons and automotive transports meant the impossibility of managing a modern war, such as the Germans carried out against Poland. In fact, according to the report presented by Graziani on May 25, 1940, the divisions of the Italian army were too lightly armed. They had 23,000 vehicles, 8,700 special vehicles, 4,400 cars and 12,500 motorcycles. Tanks numbered some 1,500 useless light tanks, and merely 70 medium battle tanks. This meant the that Regio Esercito possessed only half the number of vehicles it needed to manage something similar to the German “Blitzkrieg.” It was impossible – as Graziani said – to fill the gap, because the country simply did not have enough cars and trucks. Artillery was old and had little ammunition. Fuel was sufficient for only a few months. Italy produced 15,000 metric tons of crude oil annually. Albania provided 100,000 more metric tons. Normal Armed Forces consumption was 3,000,000 tons in peacetime; in war it increased to 8 million. Libyan oil had been discovered, but it was too deep to of use.

All this is fairly well-known. But what seems rather unknown, or little evaluated, comes from an official document, quite a relevant and reliable one, published quite long ago, namely, the minutes of the meeting held at the General Armed Forces Chief of Staff’s office in 1939. The first volume – from January 1939 to the end of December 1940 – begins with very interesting statements. During the first meeting – which included only the Army, Navy and Air Force Chiefs of Staff and the General Chief of Staff, Marshall Badoglio – held on 26 January 1939, that is to say soon after Monaco, but eight months before the war, Badoglio opened the meeting stated: “Above all, His Excellence, the Chief of the Government, declared to me that, concerning rivendicatons against France, he has no intention to mention Corsica, Nice and Savoy. These are initiatives taken by single persons, who in no way enter into his plans of action.

He declared to me, moreover, that he has no intention demanding territorial cessions from France, because he is convinced that France is unable to accept – for, by doing so, he would put himself in the condition of drawing back a possible demand (and this would lack of dignity), or to enter into a war, (and this is not his intention).”

When speaking of initiatives taken by single persons, Mussolini meant something rather well-known at that time and quite recently as well. We know about this through the memoirs of one of the most important personalities of Fascism, Baron Giacomo Acerbo, a World War I hero, who had joined Fascism before the March on Rome. He was the leader of the Abruzzo region and who was not only a remarkable world-renowned expert in economics, but an expert in agriculture too. Plus, he was a member of the Great Council of Fascism and one of the only four members of this Council who voted against the issue of the anti-Jewish racial laws. At that time, he was going to be appointed President of the General Budget Committee in the Chamber of Deputies, and in 1943 he was the last minister of finance Mussolini had before resigning in July.

Acerbo wrote:

“Mussolini’s obstinacy not to deprive himself of the cooperation of his son-in-law [Foreign Minister, Count Galeazzo Ciano, who had married Mussolini’s oldest daughter, Edda] appears more incomprehensible and deplorable when thinking of what happened on November 30th 1938. I mean that sitting of the Chamber when, during a speech by Ciano, and as soon as he [Mussolini] heard Ciano’s voice, stated the ancient territorial claims which Fascist Italy did not intend to renounce – all while some thirty deputies shouted, “viva Nizza,” and “viva la Savoia” and “viva la Corsica,” etc. And this happened while the new French ambassador, François-Poncet, was in the diplomatic seat and who had arrived after just a week in Rome, and after the re-establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries… At the end of the session, a hundred people in Montecitorio Square shouted the same things. It was a comedy prepared by Ciano himself, with the cooperation of the Party Secretary, Starace. And at that moment, we thought that it did not lack the preventive consent of Mussolini, who attended the session. On the other hand, just that evening, Mussolini, when opening the work of the Great Council censored what had happened with a curt tone: “I take exception to the scene which occurred today in the Chamber (these were almost exactly his words), and I take exception both because it was done without my knowledge and because those who organized it did not reflect that it was at least unsuitable, seeing that only a few days earlier we had resumed full relations with France.” The two responsible remained indifferent as it did not concern them… Everybody expected the resignation of the two responsible, but they conserved their places more firmly than ever.”

So, territorial claims against France was Ciano’s and Starace’s idea – and it was so far from Mussolini’s mind that he wanted to make sure Badoglio knew this, and, through him, the Chiefs of Staff. This is the first surprise: Italy – Mussolini – deprived of the supposed desire for getting into a war, and, above all, a war against France. If one might wonder whether this document is reliable, the answer is: 100%. Minutes were written and later submitted to each of the partiipants, who signed them. Only later they were submitted to Mussolini in person, and – especially in this case – there was no negative reaction, no correction, no change. In other words, Mussolini implicitly admitted that his opinion was just as Badoglio had reported.

It is certainly true that Italy was not overly friendly with France, but this was due to problems born in 1919 and never resolved. Italy perceived France and French policy toward, and in, the Balkans as a threat. That is why, for instance, the first operational plan made by the Italian Air Force in 1929 was the “Ipotesi Est, Ipotesi Ovest, Ipotesi doppia” – “Hypothesis East, Hypothesis West, Double Hypothesis” – where “East” meant war against Yugoslavia, “West” war against France and “Double” war against both nations. But all this was intended in a purely defensive way, as becomes evident when reading the plan itself.

In fact, the most important and general doctrine was the Directives for the coordinated employment of the Army Air Units. “Directives” were divided into three main parts. The first contained general issues and orders for actions above the ground; The second was about fighting at sea; the third concerned antiaircraft defense, reconnaissance, emergency airfields, emergency redoubts, and so on. The only known copies are those owned by Air Force Deputy Chief of Staff De Pinedo. These now lies in Rome, in the Army Archive, fondi acquisiti, non catalogato. The “Ipotesi Ovest, Ipotesi Est, Ipotesi doppia, considerazioni generali” exists as an incomplete copy in the same Army Archive, in fondi acquisiti, non catalogato. A complete copy, however, has been found by John Gooch in the same Archive. The only study existing about the Directives is my own, “The First Air War Doctrine of the Italian Royal Air Force, 1929,” a paper presented at the 67th annual conference of the Society for Military History – Quantico (VA), the U.S. Marines Corp University, on April 28, 2000.

French policy also gave Mussolini a lot to worry about. From the Italian point of view, France appeared to have a peculiar ability to act in such a manner as to draw the ire of other countries. In those years, not only did Italians view French attitudes as hostile toward Italy, but also premier Leon Blum made two policy errors, which further alienated Italy. The first was a Franco-Spanish pact, where Spain allowed French troops transit through Spanish territory to reach North Africa in case of war against Italy. The second was France’s announcement of sending weapons, ordnance and men to support the Spanish Republic. Mussolini did not care about Spanish affairs, but if French intervention rendered Spain a sort of French protectorate, or strategic ally, Italy could find both the exits from the Mediterranean closed to Italian shipping. The Suez was owned by a French-British company. The Straits of Gibraltar were passable because Spain owned the African side, despite British possession of Gibraltar. What if France indirectly controlled the African side as Britain controlled the European one? This could pose a threat to Mussolini’s and Italy’s strategic interests.

Errors made by politicians could occasionally be made worse by blunders made by a single official. So, it was with great astonishment that the Italian press, in spring 1939, reported that, while speaking to a meeting of French Army non-commissioned officers, French general Giraud thought it a great idea to state that a war against Italy would be “a simple walk in the Po valley” for General Gamelin’s Army. After such a declaration, made by a prominent French general, how could Italy not consider France to be a concrete threat?

But did Italy really believe a French offensive was possible? Did Italians really suppose this possibility was real? The answer is, Yes. Leaving aside unfriendly French attitude during 1935 to 1939 period, the possibility of French aggression had been carefully considered by the Italian General Staff – but always from a defensive point of view. We never find, during the whole 1939 and during the first months of 1940, anything other than putting up a defence against French attack. There is never an intention to carry out an attack against France, in Africa or across the Alps, nor any consideration of landing in Corsica or in Provence. On January 26, 1939, Badoglio told his colleagues that Mussolini, in case of war against France, had ordered: “Absolute defensive on the Libyan front, and that there was nothing to fear from Yugoslavia, and not to worry about Egypt, that is to say,the British. A bit later, during the same meeting, when speaking of possible action on the Alps, he added: “The Duce decided on only some defensive concentrations, on both the Alpine and Libyan borders.”

There was no further mention of war against France till April 1940, when, during the meeting held on April 9, Badoglio presented the “strategic rules given by the Duce,” and said, “So: defence, and no initiative on the Western Alps. Surveillance in the East. In case of collapse, exploit it. Occupation of Corsica is possible, but not probable. itis foreseen the neutralization of the air basis of the island is foreseen.” Then, action against England in Africa and in the Mediterranean was discussed. But, about the French, Badoglio remarked that “the real risk for Libya is the Army of Weygand.”

General Weygand was, at that time, considered by his Italian colleagues as the best French (even worldwide) general of his time. And this good opinion reached the man in the street through the press. This was a symptom of something different and quite more complex than the simple admiration for a good commander.

It is quite interesting, and revealing, to read comments published in the Italian press, in Spring 1940, especially given that Italy was under a dictatorship, so that what appeared in print was approved by official censorship. In effect, if something was published, it was substantially approved by the Fascist regime and reflected the regime’s mind. Thus, comments published in Spring 1940, about the military situation in Norway, and, later in the Netherlands, Belgium, and France, by one of the most well-known and most fascist Italian reporters, Mario Appelius, spoke of Weygand with a deep respect, although Appelius was quite harsh about other Allied generals, such as, Ironside, Lord Gort, or Gamelin.

Appelius covered the war since early opearations in Poland. Then, he was in Finland, and, on May 9, 1940 he was in Amsterdam. The following day, he reached Brussels under German bombardment, and soon left the city by the last train out to Paris. He vividly described what happened in those days, after his own experiences.

And, on May 15, Appelius wrote about the French: “Nobody doubts the bravery of the French Army. Summoned by the mistakes of its own politicians to sacrifice itself once again to defend England, the French Army will surely fight with the same bravery of 1914.” This is revealing of a certain propensity towards France by the Italians. In 1940, of course, one could not help but bear World War I in mind: It was the same French Army that had stopped the Germans on the Marne, in Verdun and, in 1918, in Arras and Reims. The same French Army had demonstrated during the Great War that it could lose some battles, but win the war, emerging victorious from the most desperate situation. In other words, Italians were France-friendly.

But were the French Italy-friendly? Considering the Italian “coal affair” of 1940, one could very much doubt it, at least in Italy. Mussolini and the Italian top generals, in Spring 1939, were well aware of the joint military conferences held by the British and the French in Europe, Africa (in Djibouti), and Asia (in Singapore) to define a coordinated action against the Germans, the Japanese and the Italians in case of war. And Italian top-brass knew very well that the main problem was that of maritime warfare.

Italy could sustain for a short-term, a land war, with resistance in the Alps. Air war was sustainable too, but African colonies could not be kept without maritime communications. This led to another big problem that Mussolini was aware of – the Italian fleet was not yet ready – and Allies knew it. And this problem was dire, for it hinged in the fleet, and on which depended ultimately national survival. It was the problem of coal.

As it is well known, as soon as the war began in late summer 1939, Italy announced it was “not belligerent,” which meant something similar to neutral, but was not exactly the same. What is often forgotten is that as soon as the war began, Britain and France, but above all Britain, imposed an official blockade on German goods, which evolved into an undeclared blockade of Italian merchant ships – and which above all else was against Italian coal imports.

It was a real disaster for Italy, because 75 percent of the coal needed for daily life came from other countries – by sea from England, Belgium and above all Germany. Normally, Italy needed 17-18 million metric tons of coal per year. In 1940, Italian production was 5,355,000 tons for the 17,882,000 tons needed for the year. In 1941, 17,945,000 tons was needed, while only 6,363,000 was produced, forcing Italy to reduce its import to 11,582,000. In 1942, one third of the needed 16,504,000 tons came from national sources, whilst the remaining – 10,793,000 – was imported. The Royal Navy did its best to make the blockade against Italy as strong as possible, especially from December 1939 onwards. After having met the British ambassador Sir Percy Lorraine in Rome on 30 November, Foreign Minister Ciano wrote in his Diary on December 5, 1939 that Sir Percy was going to Malta to push the British Admiral to soften the blockade and control of Italian ships. Thus, from August 1939, 847 Italian ships were stopped and their goods confiscated, for a financial loss of more than a billion liras; and ships were forced to stay in French or British ports up to one month. There was no alternative, because railway traffic was impossible without locomotives.

The same situation affected other fuels. On June 10, 1940, Italy had a 2.4 million ton reserve of liquid fuels; and in the period of June to December 1940, Italian and Albanian production did not exceed 80,000 tons, with an annual consumption of 2 million, whch, during the war, and up to September 1943, came to 8,799,000 tons. Italian production was clearly insufficient, and thus Italy depended upon imports (from June 1940 to September 1943 amounted to 3,572,000 tons from Germany, 2,150,000 from Romenia and 53,000 from other countries).

And the Allied game appeared clear when, in the winter, England officially announced that it would provide Italy the coal, if Italy accepted to provide the Allies with aircrafts, cannons, weapons and heavy equipment. In other words, Italy would receive coal, if it accepted to deprive itself of weaponry entirely and become the Allies’ arsenal. This would have been paid with coal. No mention was made, or seems to have been made, of crude oil.

The Allies did the same kind of blockade in World War I, especially in 1916-18, to pressure Norway, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Sweden and Denmark; but that time they asked for “loyal cooperation,” which consisted of organizing local trusts that gave their word to the Allies that what was bought by their own countries would be consumed in their own countries, and not sold to Germany. Thus, the Dutch Trust, the Swiss Economical Surveillance Society and the Danish Merchants’ Cooperative were established. All worked very well, especially in Switzerland, where the Swiss agreed to stop buying abroad and selling to Germany, and bought raw materials producing goods for Allied powers. Basically, in 1940 Britain seems to have looked for a similar arrangement with Italy.

Italian industrialists were quite interested, because Italian societies were selling a lot of trucks and weapons to the Allies in that period. But for the Italian government to officially accept such a proposal would mean exposing Italy to the risk of a German attack with no possibilities of defending the country, given the lack of heavy weapons, and no possibility of moving and manoeuvring troops, given the lack of oil. And this had to be done by accepting British conditions and receiving coal at a price fixed by England. Could Italy risk its integrity to receive coal to be paid in weapons at British fixed price? It was suicide. It was absurd.

So, in autumn 1939 Mussolini substantially had the alternative between the war against the Allies and the acceptance of the Allied ultimatum, that is to say an immediate war against Germany with no possibility of defence. And how could Mussolini hope to receive any help from the Allies, seeing what they gave to their friend and ally, Poland?

Some authors say that the Allies wanted to gain Italy’s help simply to turn German resources from the western front against Italy. If they failed, and Italy entered the war together with Germany, this would only weaken the German war effort, given that Germany would have been obliged to support Italy. As said, there are some Italian authors who suggest it. The most important is the late Franco Bandini, who introduced this idea in his book Tecnica della sconfitta (Technique of Defeat).

The situation appeared quite grim, especially because in that same period British and French fleets began deploying a number of their vessels in the Mediterranean. In the autumn of 1939, the Allies had seven battleships (five British, two French).

According to official information, at the end of December 1939, France had eight battleships (the Courbet, Océan, Paris, Bretagne, Provence, Lorraine, Dunkerque, Strasbourg) and England fifteen (the Queen Elizabeth, Warspite, Valiant, Malaya, Barham, Ramillies, Resolution, Revenge, Royal Oak, Royal Sovereign, Repulse, Renown, Hood, Nelson, Rodney), not considering the Richelieu, first (and only) of a class of four, which was going to join the fleet, as well as the British King George V, the Prince of Wales, the Duke of York, the Jellicoe and the Beatty. Germany had at that time the two old battleships the Schlesien and the Schleswig-Holstein (soon declassed to school-ships) and the more modern Deutschland, Admiral Scheer, Admiral Graf von Spee, Scharnorst and Gneisenau, with the Bismarck under construction. So the Pact of Steel had nine scattered battleships, against twenty-three concentrated battleships; and it could hope to have – that is after the end of construction and with no further losses in battle (after having lost the Graf von Spee in the Rio de la Plata on December 17th, and if the Tirpitz could be had on time) to a maximum of sixteen against thirty-two, (and not considering the just sunk Royal Oak, by a German U-boot in October 1939). Thus, the Allies had a one to two advantage.

The Italian fleet, at that time, numbered only two old refurbished battleships – the Giulio Cesare and the Conte di Cavour. By June 1940, two more old refurbished ships (the Caio Duilio and the Andrea Doria), along with the first two super-dreadnoughts of the «Littorio» class (the Littorio and the Vittorio Veneto).

It was clear that under such conditions, in case of war against the Allies before the end of Spring 1940, Italy would have had its fleet immediately destroyed and all its coasts devastated, with annihilation of its merchant traffic, and of many of its major cities, such as, Palermo, Naples, Genoa, Trieste, all along the Leghorn, and up to Venice.

As admiral Romeo Bernotti, the most important Italian naval strategist and theorist, stressed in December 1940, six months after Italy’s declaration of war: “In August 1939, during the period of diplomatic stress, and because of the possibility of the Italy entering the war, the Anglo-French concentrated in the Mediterranean most of their naval forces. At the same time, merchant traffic was displaced from that sea. The displacement ended during Italy’s not-belligerence period, but was presumed three weeks before our intervention. In Anglo-French plans, it was foreseen that the displacement from the Mediterranean would have had a provisional character, would have been a short-termed one, supposing Italy would have been forced to collapse, as a consequence of its naval inferiority and of the quick economical asphyxiation.”

Hitler came to the rescue, and Germany promised, giving its word to Italy, to supply all the needed coal, sending it by rail, and also providing wagons and locomotives. But how do the Germans really feel about Italy? Could Italy trust them or not? Here was another problem.

When Mussolini signed the Steel Pact with the Germans, he signed from a fully defensive position; and the same thing happened at the time of the Antikomintern Pact. Mussolini felt surrounded and isolated and he choose the only alliance he was offered. It was not the best possible alliance Italy and Mussolini could hope for – it was the only one possible. It was far from the best, especially because the German behaviour was not very encouraging. Hitler greatly admired Mussolini, but his staff did not. And, if there was any admiration, it was only for the Duce – it did not extend to Italy and the Italians.

In Berlin, Rome had two quite good officials, in the persons of Ambassador Bernardo Attolico and military attaché General Efisio Marras. Neither one was enthusiastic about the Germans; both were clear-eyed and objective. Attolico was hostile to an alliance with Germany; or, at least, of an alliance as strong as the Germans desired at that time. Attolico’s official correspondence to Rome was filled of warnings. On September 10, 1939 Ciano wrote in his Diary: “Attolico reports that… great popular masses… begin to demonstrate an increasing hostility and that words such as betrayal and perjury are frequently uttered.”

Germany expected – pretended to have – complete Italian support for its policy, right down to the last man and the last drop of blood – but with no independent decision-making power left to Italy. Here is one clear proof: Mussolini was not informed of the invasion of Poland before the attack began, despite what the Steel Pact clearly stipulated. According to the Germans, Italy could only follow the Reich and its policy, as evidenced by Attolico’s reports.

The Germans, Ribbentrop, did not like Attolico at all, and often asked that he be recalled, which happened in Spring 1940, because he was very ill and thus forced to leave the embassy and go back to Italy, where he died soon after.

But if Attolico’s reports were always dimly viewed in Rome, because of Attolico’s well-known attitude, it was not the same with Marras’ reports. General Marras was quite well liked by the Germans, who held him in good regard. He was also considered as being attuned with official policy than Attolico. That is why his evaluations were carefully considered by both Ciano and Mussolini. And we can easily see the results that his reports had.

On August 25 and 26, 1939, Marras he wrote to Rome about the atmosphere within German high command and political circles as, “Decisively close to breaking-point” with Italy, largely thanks to Ribbentrop who had done his best to convince everybody that Italy was ready to march along with Germany at the first shot.

Thus, the “non-belligerence” declared by Mussolini had a terrible and negative impact in Germany, and it was immediately reported to Rome from different sources that it had been described as “the second betrayal,” (the first betrayal being the change Italy did in 1915 when it entered the Great War on the side of Allies).

Apart from Marras’ reports, there were many other signals that could be cause for worry. All these are reported in Ciano’s Diary; and it would be onerous to repeat them all here. On September 9, 1939, Ciano reported that the Hungarian minister in Rome “…spoke clearly. He said which threat would hang over the world, Italy included, should Germany win the war… Anti-italian hatred is always alive in the German spirit, also if the Axis for a short time chloroformed it. The Duce was shaken and very upset.”

Then, there were rumors from Austria of annexing Trieste, or the whole of the Po valley. A Czech reporter described a harsh anti-Italian speech by a Nazi official in Southern Germany in 1939. There were similar reports and warnings from the Hungarian ambassador. All these added up to a hostile and wide-spread anti-Italian sentiment in the German population. It is possible that Mussolini did not care at all about these minor bits if information. But what certainly made him quite worried was the oral report Marras made directly to him in Rome, on March 4, 1940.

Ciano was there and later reported in his Diary that Marras was rather pessimistic about the German attitude toward Italy: “In spite of formal respect, he is convinced that the Germans have unmitigated hate, and worse, contempt, for us, for what they call the second betrayal. No war objective would be as popular in Germany, for the old and new generations, than an armed descent to the blue skies and warm seas. These and other things Marras honestly told the Duce, who was quite badly shaken by this.”

So, it was surely not by chance that Mussolini ordered the construction of the so-called “Alpine Wall of the Littorio,” that is to say, the mountain fortified system which was supposed to stop every entrance into Italy. The order was issued in the winter of 1940, and people worked 24 hours per day, under the artificial glare of photoelectrical light of the Army during the night, and using up all the iron and concrete available in Italy. At the same time, the Army staff concentrated Italian armoured units in the eastern part of the Padana Plain, to guard against an attack from Austria by the Reich.

Eyewitness geometrist Angiolino Savelli (in his talk with me in 1989), who had director in winter 1939-1940. In spite of all the efforts, the result was not very impressive. Engineer Corps Colonel – later Brigadier – Guido Lami, who directed a portion of the works on the eastern alpine border at that time, angrily commented: “The Germans have the Siegfried Line, the French have the Maginot and we have the Dull Line,” as Mrs. Elda Lami told me in 1990.

After the war, an author questioned the reason for such a double measure – standing and mobile defence, respectively represented by the Alpine Wall and the tanks unit – and some critics said that it was proof of tactical uncertainty and a waste of resources. But, apart from the fact that it had clearly been done after the 1917 experience, when, after Caporetto, the standing defence had been unable to stop the amassed and fast-moving enemy, and there had been nothing on the rear-line to stop them – now, in 1940, it was not a mistake, but the only way to stop a motorized German offensive able to pass through the fixed mountain defences.

And what was the German reaction, if any? Marras reported that the German general staff, in Spring 1940, long before the attack on the Netherlands and Belgium, had hinted that it had increased the forces in Southern Germany and, as Marras wrote, perhaps as a silent response to the rumors published by the press about the Alpine Wall.

When considering all these factors, it is most interesting to follow the evolution of Mussolini’s attitude toward the war during winter 1939-1940, according to what Ciano reported in his Diary. In early 1940, Rome warned Brussels and Amsterdam that Germany was planning an attack on them. By doing so, it meant to stymie the path that the Germans had chosen. And on January 3, 1940, Mussolini sent Hitler a friendly and decisive letter, which was received on 8 January 8th. In it, Mussolini suggested that Hitler reach a negotiated peace with the Allies, leaving Poland as a demonstration of good will, and he told Hitler that Italy reserved the right to enter the war only at the most favourable moment.

Ribbentrop summoned Attolico and asked for an explanation. Did Italy think, or was Italy insinuating, that the Reich was not able to win the war? And what was that “most favourable moment?” It was clear that Italy had no intention of remaining fully allied with the German plans and desires. Unfortunately, it was too late to change Italy’s position.Mussolini’s mistake was made back in 1938, when, after the so called “Easter Accords,” where England officially recognized Italian rule in Ethiopia, and until the signing of the Steel Pact, Italian foreign policy had the opportunity – a 10 months long opportunity – to leave the rigid trap in which Germany was putting Italy, and it was mainly because of Mussolini that this opportunity was lost.

And later? One can easily imagine how the “Italian betrayal” would be repaid by the Germans.

Here, I think there is room to open a broader discussion, as to whether or not this was the major and most probable reason for Italian engagement in World War II. According to what has been discussed here, one may conclude that it was not to gain territories (by the way, Mussolini had foregone all that in January 1939), although the new situation could permit to take something, and even permitting Mussolini to think of territorial acquisition. It seems also more than possible, if not probable, that Italy declared war because Germany was going to win the war, and England was going to lose, while the United States could not enter the war because American public opinion rejected this possibility and their President had first to think of his re-election in the fall of 1940.

The American Presidential election in 1940 was gearing up to be the harshest ever had in the USA, because the Democrats had nominated Roosevelt for the third time, and the Republicans opposed him saying that no Presient had ever ruled for more than two terms. In order to win, Roosevelt inserted two Republicans – Stimson and Knox – in his cabinet, giving them the War and the Navy Secretariates, and, above all, promising the people not to involve the USA in the European war. The result was quite good in terms of State ballots – Roosevelt gained 38 out of 48 – but inferior to the previous election in number of ballots, because in Autumn 1940 Roosevelt received 27,243,466 votes and his adversary 22,304,755, that is to say, Roosevelt got 54,98%, whilst in 1936 he had received 24,751,597 against 16,697,583, that is to say, 59,71%, and he got 46 out of 48 States. Under these conditions, it is obvious that nobody in Winter and Spring 1940 could be 100% sure about the prosecution of Roosevelt’s policy after December 1940, because there were some doubts about his victory in the Presidential election in November; and, above all, it was quite hard to even suppose an American intervention after what Roosevelt had promised.

And, above all, because June 1940 was the month when the Italian fleet got four battleships the Caio Duilio, the Andrea Doria, the Littorio and the Vittorio Veneto, with a fifth one forthcoming, the Roma. This ensured naval parity in the Mediterranean, the safety of the coasts, the protection of maritime traffic with the colonies the end of the British threat, which had begun in September 1939. In effect, Italy was looking at equalling the British in weaponry, siding with the indicative winner of the war (Germany), and in order to give Germany no possibility of attacking and destroying Italy after the victory over the Allies.

It may all seem absurd now, but only because all are accustomed to think that Mussolini declared war to gain something as a jackal and no more. But if we carefully consider the situation as found in the documents and as seen in the Italian economic, political and military situation of that time, I wonder whether any doubt can still remain. Mussolini feared German victory and was practically sure that Germany’s next move would be, soon or later, against Italy; and Italy was too weak to resist. Russia was allied to Germany, the United States – better, the American people, except for their President, who was ending his second term by the end of 1940 – were far removed from the idea of going to war to support England. And, as for England – hostile – was beaten on land and sea, France was invaded and destroyed. What remained for Italy? Who would and could support Italy? Franco? Salazar? Japan? Against Germany? Unbelievable.

Let’s go back to Acerbo’s rather rhetorically written memoirs, where we find a confirmation, which, errors excepted, is the only existing one: “In taking his decision, it is also possible that he [Mussolini] feared the Teutonic dragon, which he himself had fed and which would swallow the whole of Europe, and damage, in the process, the interests of Italy which had already lost its traditional position of influence. As an effect of the incredible German victories, which embodied the Nazi concept of the ‘Lebensraum,’ Mussolini, attracted by the sound of this concept, also quickly inserted it into the list of our claims, not caring if this concept suited our specific needs, or if it strengthened the Reich’s pretension. But ‘Lebensraum’ was inherited from the Second Reich, that is, the need of the German nation to have a way down to the Mediterranean through Trieste. And one must add that the exalting of that people’s super-nationalism, grown red-hot by of the military victories, now menaced to undo the agreements concerning the Upper Adige… So, according to Mussolini, it was better not to linger anymore in taking sides with the winner, if we wanted to avoid irreparable misfortunes on us, and, at the same time, to participate in the sharing of the booty. It is not to my knowledge, by the way, that Mussolini, during military meetings or occasional talks in the days before the intervention, pointed out this argument, to support his decisions. One began talking about it only later, when the fortunes of war were taking a turn for the worse for us, to justify the irreparable step taken.”

So, according to Acerbo, the fear of what the Germans could do after their victory existed, but how should we be surprised if Mussolini does not mention it in 1940? For a long time, he had glorified Italy’s power, exalted Germany’s friendship, and attacked France and Britain. Thus, how could he now say that he was joining Germany in war because he not only distrusted it, but because he feared it? Would he not cut a very poor figure? So, it is no surprise that these two reasons are never mentioned, not even in the slightest of conversations. Mussolini did not say these reasons, because he could not lose face.

As for everything else, all that Acerbo reports is true and can be verified through, for instance, Ciano’s Diary. Thus, it is true – and Ciano reports it – that in Austria and in Germany people, from the lowest level up to some Gauleiters, openly spoke of taking Trieste and the Friuli. It is true – and Goebbels wrote it more or less clearly in his journal after September 1943 – that the Reich liked the idea of pushing its border south of Venice. And it is true that, despite the formal agreements about transferring people (those who chose to do so) from Upper Adige to Germany, the Germans were involved in chicanery, in the autumn of 1939, so that it seemed that everything was delayed until the end of 1942, while in actuality, the transfer was to proceed a lot faster.

Therefore, Mussolini chose war. Again, Acerbo reports that he was made aware, by Marshall Rodolfo Graziani, after the war, while they were both in jail, on Procida Island, awaiting trial: “…of a briefing Mussolini held on April 10th [1940] with the commanders of the military (including the Crown Prince) and the Army Corps, and that he secretly announced that Italy was going to enter the war, specifying, ‘not together with Germany, nor for Germany, but on the side of Germany.’”

Immediately thereafter Acerbo comments that it was: “One of those alliterations he loved so much, and with such clumsiness, he was sure, in his last years, to unravel however an intricate a matter might be, and thus to overcome every obstacle and pass over the steepest position!” Acerbo knew Mussolini quite well and spoke about him carefully. But we must admit that this phrase may also be explained that Italy entered the war because of the fear of Germany – thus, not allied to the Reich, not to give the Reich advantage, but on the side of the Reich; and, we might add, in order not to give the Reich a reason to attack Italy afterwards.

Was Acerbo the only eyewitness? No, there is further evidence, starting in the spring of 1939. On March 15th, Ciano and Mussolini were concerned and worried about the German annexation of

Czechoslovakia. Quoting Dante Alighieri, Mussolini told Ciano that the thing to do was “To accept the German game in order to avoid being ‘unpleasant to God and to His enemies.’” In the days that followed, Mussolini and Ciano talked about this issue. Ciano wrote: “Egli thinks the Prussian hegemony in Europe is already established. He thinks that a coalition of all the other powers, including us, could slow the German expansion but could not stop it… I asked whether in such a condition it is convenient for us to make the alliance; or, instead, to keep our full liberty of choosing in the future, according to our interests. The Duce shows himself to be clearly in favour of the alliance.”

This is not exactly an admission, but there is more. News about the bad attitude of the Germans toward the Italians came through many channels, and on August 18, 1939, five days after having seen Hitler in Berchtesgaden, Ciano wrote that Mussolini “fears Hitler’s wrath. He thinks that a denunciation – or anything similar – of the [Steel] Pact convince Hitler to abandon the Polish issue get Italy to foot the bill.”

But this too must be considered carefully, for it could be a sort of self-defence by Ciano. However, it becomes additional evidence when you we place it in context with what Acerbo wrote. Regardless, we have more.

On September 9, 1939, the Hungarian ambassador told Mussolini that, should Germany win the war, a terrible threat would descend upon the whole world, including Italy.

On September 10, the Italian ambassador to Berlin visited the Duce and told him that the German people, when told of Italian non-intervention, started speaking of betrayal.

On September 30, according to the minister of National Education, Giuseppe Bottai, when speaking of fuel supply-chains needed by the Army and the Air Force, Mussolini said that he did not want to start the war until he had them: “With whom and against whom? A quick hint: ‘… until these reserves are met, we shall not engage – not with group A, nor with group B.’ The possibility of a choice between two rivals yet existed.”

On December 8, 1939, there was a long meeting of the Great Council of Fascism about the Italian position. After an order by Mussolini, Ciano detailed the whole situation. Ciano related all the tricks and lies of the Germans up to that moment. In his Diary he briefly mentions this, but Bottai reported that Mussolini said: “Italy? She declares her loyalty to the pacts (“don’t we have, by the way, also a pact with England?”) – and waits the outcomes. Here there are two empires in a fight, two lions. We have no interest in an overwhelming victory of any of the two. If England should win, she will not leave us other than the sea for taking a bath. If Germany [should win she will not leave us] even any air to breathe. One can only wish that the two lions tear each other to pieces, leaving just their tails on the ground. And that we go and pick up their tails.”

A few more rumors of unfriendly German attitude were reported in the next few weeks. Then, on March 4, 1940, the Duce met General Marras, the Italian military attaché in Berlin. Ciano reported: “I accompany the Duce to General Marras, who is rather pessimistic about the German mind toward us. “In spite of formal respect, he is convinced that the Germans have unmitigated hate, and worse, contempt, for us, for what they call the second betrayal. No war objective would be as popular in Germany, for the old and new generations, as an armed descent to the blue skies and warm seas. These and other things Marras honestly told the Duce, who was quite badly shaken.”

According to Ciano, on April 10, 1940, after the German occupation of Denmark and landing in Norway, Mussolini said: “The King would have us join in, just to pick up the broken pots. Hope they will not break them on hour heads!”

Who were “they?” Ciano does not say; nor does he say whether Mussolini later was clearer about it. But when considering the contemporary situation at that moment, it’s hard to think that “they” could be the Allies.

It is true that after August 18, 1939, Ciano never wrote that the Duce feared the Germans. But he told other people, at least Bottai, who, on March 29, 1940 noted in his diary that Ciano, when speaking of Mussolini, told him: “Germany winning by herself alone frightens him.” Said this way, this may mean that Mussolini was frightened, as he thought that Germany could act against Italy after having won in the West. But this may also mean that if Germany won without Italian help, Italian diplomatic situation would be weaker. Which of the two? We don’t know. But there is additional evidence of Mussolini’s fear, and we get it from Filippo Anfuso who, at that time, was the Chief of the Office of the Foreign Minister Ciano. Anfuso wrote in his memoirs that when, in Spring 1940, Mussolini noticed that Goering asked the new Italian ambassador in Berlin, Dino Alfieri, the date of the Italian intervention, he said: “… if Goering spoke that way, it seems clear that we cannot back down. After France, one day, it could be our turn, and it would beat everything to have signed a Pact called a Steel Pact and then to be invaded by Germany and be on top of the anvil.”

That should be enough, but we have more. General Roatta, who had been the military attaché in Berlin before Marras and later became one of the foremost army commanders, wrote that Mussolini, during the period of neutrality: “… considered the possibility if not to enter the war on the Allied side, the at least to have to face some excessive German demands and prevarication. He perfectly realized, at that time, the German mentality and the dangers she could pose for us. In November ’39, when I was back from Berlin – where I had been military attaché – to be appointed Army Deputy Chief of Staff, Mussolini asked me what I thought about the future intentions of the Reich, and about the countries occupied during the war, and I decidedly answered that, in case of victory, the Reich will annex, in one way or in another, not only the occupied countries, but also the states nearby, excluding none, and introducing in all of them what in Berlin was called “die deutsche Ordnung,” that is to say “the German order.” This assessment the Duce heard without any surprise.”

This is important, but not definitive, because it took place about November 1939. Although this is less important, or had lesser influence, than what Marras said in March 1940, nevertheless, together with the others, it too provides additional evidence for the larger view, and underlines a continuity between what Roatta said and what Marras confirmed six months later.

The second source is provided by general Emilio Faldella, in his L’Italia e la Seconda Guerra Mondiale, first published in 1959. Faldella was a veteran who had been in the military intelligence and then was the chief, in 1937 to 1939, of the Italian Military Mission in Spain to General Franco. Later, Faldella was appointed to many important posts, and had deep inside knowledge about a lot of things. In the first chapter of his book, he wrote three times that Mussolini (in 1939 to 1940) feared German revenge or retaliation. Faldella wrote that on May 11, 1940, after having received the message dated on May 9th, announcing to him the German attack on France, Mussolini “revealed to Sebastiani his intimate thoughts: ‘If we continue with neutrality, as many would like, we too will get a nice Pope’s indignation telegram to be flapped in front of the occupying Germans!’ The fear of German revenge increased as time passed.”

The second mention of Mussolini’s fear is made by Faldella quoting the already mentioned witness by Anfuso. The third is Faldella’s own opinion. He writes: “The more the possibility of a German victory appeared certain, the more Mussolini feared Hitler’s revenge.” We have two problems here. The first is that the latter assessment, if Faldella’s own (and whoever has dealt with Italian military history knows how reliable and cautious he was), he wrote, one can easily assume, by way of personal knowledge, derived from his position before and during the war. The second problem is about Sebastiani’s quotation. As is known, Osvaldo Sebastiani was Mussolini’s personal secretary from 1934 to 1941. Unfortunately, Faldella, as was normal at that time, did not mention the source of that Sebastiani’s quotation. Sebastiani mysteriously disappeared in 1944 when some unknown people picked him up at home. It would be very interesting to know where Faldella found that information. But that is now impossible find. But we can admit that given Faldella’s uncontested reliability, what he wrote must be true indeed.

The last eyewitness is the former Minister of Colonies Alessandro Lessona, who, in his memoirs, wrote twice that Mussolini entered the war because he feared the Germans.

Here, we have an additional reliability problem, Lessona left the ministry by the end of 1937, and in 1940 was simply a professor at the university of Rome. His memoirs appeared only in 1958 and must be taken cautiously, for he could have modified facts here and there. Of course, one of Lessona’s cousins was General Pirzio Biroli, an army commander, and Lessona was on very good terms with many prominent people of the Regime, including Badoglio, Balbo and Bottai. Thus, he could have known from one or some of them about what he wrote; that is to say that in 1940 Mussolini felt the victory to be on the German side and. “Thus, convinced of serving Italian interests, he intervened in the war to prevent the winner getting his revenge on Italy, when the winner was disposing the future of Europe.” Many pages later, he says, “The tragic decision of entering the war (I, who was absolutely against it, must say that) has a moving reason: That of having thought to give the Italian people at last the hoped-for prosperity, and to safeguard the people against revenge in case of a German victory.”

It is impossible to assess whether what Lessona wrote was due to what he knew from a first- or second-hand source; and, if the latter, we do not know which source it was; nor we can determine whether (in case it was only his personal opinion) it was grounded in political reality, or was simply an attempt to justify Mussolini. Regardless, when added to other evidence. Lessona’s witness is validated, whose reliability is indirectly confirmed by all the others I have already quoted. Thus, it is an additional brick in our construction,

In order to avoid the war with Germany, the only thing Mussolini could have done was to join Germany, thus calming the Germans and depriving them of the possibility of complaining and protesting for the lack of any Italian commitment. Thereafter, he would fight a parallel war – as it was called – by continually avoiding German involvement with Italy, and to gain whatever was possible. But most of all to wait, and keep Italian forces as much intact as possible, in order to resist German encroachment, and, if possible, meet the clash with Germany which one could predict was not so far off in the future. Italy did not want such a clash and had done what it could to avoid the war. But now neutrality was no longer possible. It was either war alongside the Germans, or war against the Germans. But absolutely, war. Thus, on June 10th. Mussolini made the announcement to the world.

We know that Mussolini imagined that peace talks would begin shortly; with only a few weeks of war and a few casualties. The few casualties, however, had their own political and military impact. Moreover, as said and as an appalled Marshal Enrico Caviglia remarked in his journal, Italy had practically no money, as the competent minister admitted in front of the Chamber of the Fasci and Corporations – the new name of the Chamber of Deputies.

The situation remained critical and Mussolini decided to safeguard Italian military power in case of a German-Italian clash in the post-war era. In the best-case scenario, the current war would weaken Germany so much that Hitler would prefer not to attack Italy. In the worst-case scenario, Italy would at least have the power to resist. Conversely, the Germans looked with suspicion and derision at Italy. Marshal Caviglia wrote that under these circumstances, Italy undertook a very strange strategy – to declare war on France and Britain but only move forces when the end of the war was near. This way, Mussolini could demonstrate that his troops were fighting and it would be sufficient to claim territory as compensation for participation.

Additional proof of this approach by Mussolini may be given by the armistice with France. As is well known, the Italian offensive on the Western Alps was a failure; and it is also well known that no attempt was made against Corsica, Provence, or the French colonies, such as, Tunisia and French Somaliland. It is true that a landing in Provence would have been difficult, given the French stronghold of Toulon. But one must also remember that if Italy did nothing against France, France had a lot against Italy, despite the brief shelling of Genoa and some other irrelevant shelling along the Ligurian coast.

What happened after ceasefire ceased well known too. Italy was on the winning side but asked for only 83.271 hectares, that is to say 832 square kilometers and three quarters. It was definitely not much, especially when discovering that during the Italo-German meeting held on June 18, 1940 in Munich, Hitler recognized the right of the Italians’ demand to occupy continental France up to the Rhône, as well as Corsica, Tunisia and Djibouti. But this was not enough for Hitler: He also advised Italy to widen the occupation to a belt along the Swiss border, to link the German occupation zone to the Italian one, thus isolating non-occupied France. Hitler hoped to extend the Italian occupied zone right up to the Saône, including any good railway line which the Italians were free to take. General Mario Roatta, the former commander of Italian volunteers in Spain, who spoke excellent German, on June 20th chose the line linking Chambéry, Dijon, and Bourg-en-Bresse and submitted his project to Hitler in person, who then also approved the project of giving Italy another similar railway into Spain, such as, the Avignon-Nîmes-Perpignan line, consequently widening the Italian occupation of Southern France.

But Mussolini refused. In fact, Roatta and the Italian mission had achieved a great result, far more than what one could expect after what was done on the Alps. So, why did Mussolini not accept it? And, above all, why did he not accept, when considering that on June 23 German military attaché Enno von Rintelen gave Roatta a personal telegram from Hitler, in which Hitler asked Italian troops be sent to a zone twenty kilometers from Geneva, in order to join the German forces, and when considering that the Wiesbaden Italo-German agreements of June 29, 1940 left to Italy a portion of French territory up to the Rhône?

This seems to be quite different from what is normally known after the surviving draft of the minutes written by P. Schmidt. But while German documents were mainly destroyed during the war, practically all the Italian documents survived. So, both the Italian official accounts published by the Italian Army Staff’s Historical Service were written after a careful and long consideration of the original documents, still conserved in the Army Archive in Rome. Further details could come from General Roatta’s private archive, which is still the property of the Roatta family, and remains inaccessible. The only point the Italian documents have in common with Schmidt’s draft is that Hitler asked Mussolini not to ask the French for their fleet, explaining that he feared this could push the French to give the British all their ships.

The reason is given by the official Italian account about the occupation of France, where is highlighted an aspect previously remarked upon in other official accounts about the Western Alps campaign. When Mussolini asked Roatta how many divisions were needed to garrison occupied France, Roatta answered that, before the foreseen disarmament of the French Army, Italy must keep there at least fifteen divisions, which later could be reduced to ten, but never less than ten. Mussolini replied that he could demand from France nothing more than what had been already been taken. that is to say, nothing or a just little more. This has always been seen as a bad conscience and the acknowledgment of the poor performance by Italian troops on the Alps. But, as both the official accounts underline, in June 1940, the Italian army had in Italy only fifty-three divisions; and sending fifteen divisions would seriously deplete the army. That is, or at least could be, a concrete reason to explain why Mussolini refused. And it a far more concrete reason than either conscience or shame.

Hitler would use a widened Italian occupation as a way to reduce the number of German troops garrisoning in France. But Mussolini probably looked at it as a problem. Having a huge number of troops far from their supply points, close to the Germans and separated from Italy by the Alps meant too many troops, too far away – thus, too much risk, too many problems. Thus, best to do nothing at all. Both official accounts suggest that Mussolini acted this way because he was thinking of further conquests and needed troops. My opinion is that this was added demonstration of what was probably Mussolini’s fear – he considered the Germans more a risk and potential enemy than as an ally, and thus he preferred to keep in hand as many troops as possible. The discussion – if any – is open.

Ciro Paoletti, a prominent Italian historian of military history, is the Secretary General of the Italian Commission of Military History. He is the author of 25 books, and more than 400 other smaller works\, published in Italy and abroad, and mostly dealing with modern and contemporary Italian military history and policy.

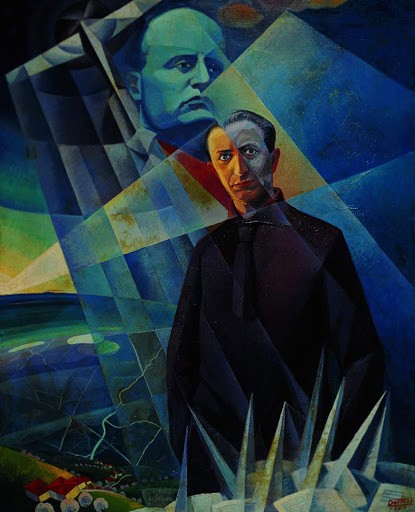

The image shows An Italian poster of Mussolini, an aerial portrait by Mario Carli, painted 1931.