In the mid-1980s, the middle-aged English philosopher, editor of The Salisbury Review, wrote a column in the London Times, in which he noticed that the Austrian throne is empty and pointed to Otto von Habsburg who could fill the void. To some readers, even if they happened to be British subjects, his idea, I suspect, must have appeared facetious. However, Roger Scruton, the author of the column, who was knighted by Prince Charles in 2016, was a serious man. What others thought could be a joke, to Sir Roger was a serious matter. He spent his life defending and giving fresh meaning to what the progressives consider outrageous only because it is old or appears obsolete.

To be sure, the defense of monarchy in an environment in which democracy is thought of as divine, sounds like a sign of madness. Yet nowadays when democracy is performing very poorly and almost every week provides more and more evidence that discredits it, perhaps it is time to rethink our uncritical attitude to it.

On October 9, this year, the Austrian Chancellor, Sebastian Kurz, announced that he would resign, after prosecutors began an investigation into allegations that he used public money to pay off pollsters and journalists for favorable coverage. Eight days earlier, on October 1st, the premier of Australia’s New South Wales, Gladys Berejiklian, “stepped down over a probe into her secret relationship with a lawmaker who is being investigated for corruption.” And on September 30th, former French President, Nikolas Sarkozy, was sentenced to one year for illegal campaign financing. All three scandals happened within less than two weeks.

This is not all. Remember the arch-popular Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva? In July 2017, he was convicted on corruption charges to 10 years in prison. In 2016, the world learned about the so-called “Panama papers.” It was discovered that over one hundred world leaders had offshore accounts to evade paying taxes.

Among them was Oxford-educated “philosopher king,” Abdullah II, of Jordan, who purchased three Malibu properties with the help of offshore companies for $68 million, in the years after the Arab Spring, when his subjects protested against corruption. But kings are kings and have always been in the habit of ripping-off their subjects – something which partisans of the popular government promised democracy would put an end to. Apparently, one does not have to be a king; enough to be a democratic head of state to do what corrupt kings do. The Panama papers include two British Prime ministers – Tony Blair and David Cameron – the Premier of the Czech Republic, several people associated with the Clinton Foundation, and many more.

The USA – the bedrock of democracy – is not a place to look for honest politicians, either. In fact, the US is infested with dishonest politicians, many of whom rot in prison, put there by their electors. In Baltimore, where I resided for almost 15 years, all three mayors during my residence there had to step down on corruption charges. In 2014, Bob McDonnell, the governor of the neighboring state of Virginia, and his wife, Maureen, were indicted on federal corruption charges; so was the governor of Illinois, Rod Blagojevich (who was sentenced to 14 years in prison), as well as three other governors of the same State.

If you still believe that democracy is a solution to the problem of corrupt government, you’d better read Plato’s Republic or Gorgias, or buy a lantern and, like Diogenes in Athens who tried to find an honest man, look for an honest civil servant who puts the good of those who elected him before self-interest. Many of those who believe democracy to be the best confuse commitment to democracy with commitment to simple human honesty and decency. Unfortunately, when it comes to honesty, democracy does not score higher than other regimes and is likely to continue being the source of frustration to those who put their faith in the people.

The list of corrupted democratic politicians will continue to grow in; and this is not a question of probability but certainty. Democracy, it needs to be stressed, provides more transparency than any other system; it may have eliminated the arbitrary brutal use of physical violence by the politicians, which means that we no longer need to be afraid of living under autocrats like generals Pinochet or Franco and shah Reza Pahlavi, or African political gangsters, like Paul Biya of Cameroon, president since 1982, who exploit and abuse their people. However, as thirst for blood among democratic leaders goes unsatisfied, they instead turn filling their pockets and deceive the naïve public that they serve. That is why the system is not working very well.

An army of naïve political scientists and commentators write books for the believers in popular government on “how to save democracy.” The journalists of the Washington Post lie to the public that “democracy dies in darkness,” while supporting corrupt Left-wing politicians. Social activists, on the other hand, scream louder and louder that the only way to save democracy is to expand it even further. The last suggestion is the surest way to corrupt even more people. Absolute power may corrupt absolutely, but any amount of power will also corrupt – which means that allowing more people to govern will also corrupt a greater number of them. In recent decades democracy started looking like a place where everyone could enrich himself. The careless get caught; others get away; and ordinary people get no share in the big pie.

Thomas Jefferson was an idealist who, as we learn from his letter to J. Langdon, 1810, thought that hereditary monarchs were “all body and no mind,” who can do nothing but mischief. But he was also a realist who knew that the only way to make democracy work is, as he explained it John Adams in a letter of October 28, 1813, to find natural aristocrats to rule over the rest: “The natural aristocracy I consider as the most precious gift of nature for the instruction, the trusts, and government of society… May we not even say that that form of government is the best which provides the most effectually for a pure selection of these natural aristoi into the offices of government.”

That was two hundred and eight years ago. Today we can say that Jefferson was mistaken. The democratic environment, which tends to grow and destroy non-democratic elements around it, is fundamentally hostile to creating conditions in which aristocratic virtues can grow. Rather, the opposite is the case – under the influence of democracy even royals succumb to the democratic malaise. It happened to Prince Harry who has recently left the confines of Windsor Castle to settle down in democratic America. So far, the news for the lovers of monarchy is not good. Instead of transplanting aristocratic virtues to America, Prince Harry has become a celebrity. He began his life in the New World by whining on Oprah Winfrey’s show how miserable it is to be a royal and how nasty other royals can be. If you are emotional, you can even feel sorry for him – he is presented as a man who suffered greatly under the heavy yoke of the aristocratic code.

We should not be surprised, however, why democracy suffers from malaise. The political consequence of the decline of aristocratic order was described by the English poet and literary critic, Matthew Arnold. In his essay “On Democracy” (1879), Arnold saw what Jefferson (most likely because his dislike for hereditary aristocracy deprived him of objectivity) missed. He points out that there where aristocracy does not exist, ordinary people are deprived of the ideal that can ennoble them. Where are the Washingtons, Hamiltons and Madisons today? Arnold exclaims in his essay, pointing to the fact that American democracy is unable to regrow the greatness which one found in the generation raised when America was part of the British Crown. What grew instead was the power of the State.

Arnold, it seems, was right, which is testified by the language used in democratic countries. “The most powerful man in the world,” and “the most powerful woman in the world” (as Americans refer to the President and the First Lady); or “the most powerful country in the world” – all are part of everyday journalistic vocabulary in America. (Even the presence of the omnipotent Xi Jing Ping at the same dinner table is unable to change this democratic perception).

It would be wrong to think that such expressions mean that Americans are self-obsessed. Rather, they point to what Matthew Arnold predicted must happen. When a country lost its highest class which “dictated the tone for the nation,” the nation tended to augment the power of the State to see it as dignified and great. However, this democratic jive is not peculiar to America. It can be found in France, another country in which democracy, too, took very deep roots. The President of the Republic acts and looks (especially during the swearing in ceremony) like a secular king, anointed by the people. His residence, the Presidential Palace, just like the White House, reminds you of royal residence.

This is not so in Great Britain. 10 Downing Street looks like an unpretentious townhouse which you see all over London or Baltimore; and it was so even at the end of the 19th century when the British ruled over one fourth of the globe. British Prime Ministers behave like “civil servants.” The reason is simple: Prime ministers in a constitutional monarchy have someone above them, which is a reminder that the power of the people has limits. Whatever a Prime Minister may think of his great talents, the existence of the monarch, even if only symbolic, has a tempering effect on the Prime Minister’s ego. That is why we can’t imagine someone like Donald Trump as British Prime Minister. Were it to happen, I suspect that the British would likely choose to live under a real, not symbolic, monarchy.

10 Downing Street

Presidential Palace, France

Monarchies are a common heritage of all those who look for the cultural roots of Europe. The British monarchy is not the only one in Europe. Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxemburg, Spain, Denmark, Sweden, Monaco and Norway are monarchies, too (the Bulgarian king Simeon lives in Spain). But the British monarchy is the most visible and its well-being should matter to everyone. It is the most powerful symbol of the old order which is obsolete only to those who put faith in a system that is far from being ideal. For this defective system to work for the common good we need to be very vigilant. The proclivity for corruption of the managers of this system is (or should be) all too obvious and given the fact how often these managers of democracy are charged with financial impropriety, one may wonder whether any constitutional monarch would survive if he was so often implicated in corruption scandals.

However, what should worry us more than financial scandals are the totalitarian tendencies which democracies developed in the last several decades. Monarchy is a place where a nation finds the continuity of its tradition while totalitarian regimes erase all traces of the past. Democracies today are in the process of doing just that. Changes in the language so that it mirrors an egalitarian worldview, destruction of monuments, changes in educational curricula, forcing us to accept the idea that sex is a matter of choice are the most visible signs of the break with tradition. However, why that is the case should not surprise us. The past and human relationships tell us that reality is hierarchical. Hierarchy is what the progressive egalitarians are against. The past stands in their way to claim absolute power.

There is only one other institution which is like monarchy: it is the Papacy in which the Catholics, regardless of their nationality, find the continuity of their tradition. In one respect, the Papacy is an even more powerful symbol than monarchy – it is older than any single dynasty, and it includes our Greek and Roman heritage, while the monarchy is national. To be sure, not all popes were saints. Only a few of them lived a life which would lead anyone to heaven. But saintliness of life applies to individuals, while tradition is group behavior. When it is based on high ideals, tradition translates into noble behavior of a group, which we call a nation. The function of tradition is to provide us with signs that lead us in this life. Without clear signs on how to behave, nations are lost. They become demoralized and are in danger of indulging in monstrous behavior.

The monarchy will last as long as the royals behave like royals. This is what they owe us — ordinary people. We do not need royals who act like celebrities; we need the aristocracy to ennoble us, take us to a higher level. Once royals act like the commons, the monarchy will vanish; and when that happens, the future will likely, once again, belong to nationalist democracies turned totalitarian. As 20th century experience teaches us, democracies tend to collapse in times of crises and generate hard-core dictatorships, outside of which there is no source of values except ideology.

Mr. Trump acted like those mad kings described by Thomas Jefferson in his letter. But the problem with Jefferson’s argument against monarchy, which is the only one he formulated, is that one can always dethrone a mad ruler and replace him with a sane one. However, it is impossible to dethrone a population seized by egalitarian madness, enticed by populist demagogues who speak like Mussolini or Hitler. Seeing Greta Thunberg on the throne of Sweden would be something truly terrifying. We can only hope that the Swedish king, Carl Gustaf, will continue to rule with dignity, as he has done for many decades, and that monarchies will survive to save us from mad populists and democratic egalitarians.

Zbigniew Janowski is the author of several books on 17th century philosophy, as well as, Homo Americanus: The Rise of Totalitarian Democracy in America and is the editor of John Stuart Mill’s writings.

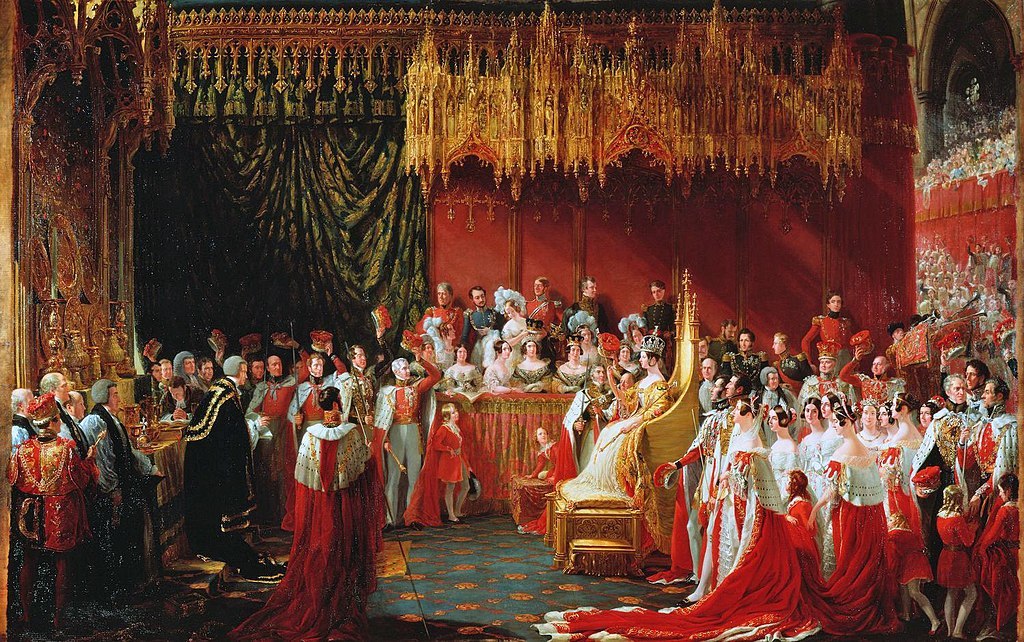

The featured image shows, “The Coronation of Queen Victoria in Westminster Abbey 28 June 1838,” by Sir George Hayter; painted in 1838.