When it comes to the Haitian Revolution, history’s verdict is clear: Haiti is a failed state and always has been. A violent slave revolt 200 years ago does not a country make. Today, Haiti remains a cesspool of filth, poverty, and corruption. It is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, with a per capita income of just $2,370 a year. Haiti is in fact the very poster child of such failed states, what a previous U.S. president of some acumen colorfully described as a “shithole” or pays de merde, in French.

Haiti’s revolt, after taking only a few royalist appointees off their own local chessboard, quickly became a full-fledged rebellion of the enslaved against the Napoleonic sham-republic. When it became clear that Paris would keep trying to balance the books with the blood of their uncompensated labor, Haiti’s sugarcane fieldworkers ended up murdering every white man, woman, and child on their side of the border, swiftly dominating the whole island through greater numbers and Madrid’s simultaneous fall to Napoleon—two centuries ago exactly in February.

Revolutionary glories from this wave of 19th-century globalization have long since faded in a state named the “Republic of NGOs” in 2010—after an earthquake so violent saw the country taken over by do-gooders from the United Nations and a host of international “charities.” The international third sector, in turn, bestowed the island with more corruption and other terrible consequences, including a very long list of sex crimes. More than a decade after the quake, Haiti’s presidential palace remains in ruins—a fitting symbol of what the Haitian state is good for after so much hand-holding.

The failure of the “international community” to deliver results in Haiti is a central plank of the anti-globalist argument and merits further study. Power abhors a vacuum, as the saying goes, and as surely as any of the laws of physics, the power vacuum in Port-au-Prince—exacerbated after the murder in his home of the sitting but term-expired President Jovenel Moïse—has finally created a great sucking sound loud enough to attract ne’er do-wells from the world over. Globalized conflict has arrived in a region otherwise characterized by universal accord—at least between states.

A 300 percent increase in kidnappings over 2020—already a historically high year for such a nefarious metric—denotes the fragile and collapsing authority of Haiti’s so-called central government. Even those who wagered in favor of progress have retreated to safety across the border (where a wall is going up) in the Dominican Republic. The process of state formation appears to be happening from scratch, with multiple warlords competing in the market of violence for primacy over land masses containing taxable population (prey, in libertarian parlance) and strategic sinecures such as port facilities and border crossings.

Worse, there appears to be a replication of the Syrian civil war playbook, with a handful of foreign powers backing various promising consortia of competitors within the thriving lack of monopoly on violence. All of this is occurring just 700 miles off the U.S. coast.

The police force the Clinton Administration foolishly imposed on the country after disbanding the Haitian armed forces has itself melted into these gangs, with street-level bureaucrats as prosaic as one beat officer pseudonymized as “BBQ” (an alias bestowed after burning down 400 residences with their residents inside, a war crime) posing as a viable alternative to the central government. Despite his appearance on the U.S. Treasury Department’s sanctions list, Jimmy Chérizier (a.k.a. BBQ) has recently enjoyed a star turn on such state-backed stalwarts as Al Jazeera, sports modern weaponry of Israeli vintage, and has been seen in the company of executives from the Wagner Group, a Russian mercenary organization. The Chinese also have their eye on Haiti.

All of this has unfolded under the blind eye of the American-backed Haitian central government and police, led by Prime Minister Ariel Henry. Haiti’s Leviathan has feet of clay, even when led by decree without a legislature and a dead head of state. The Dominican Republic, which shares the troubled island of Hispaniola, also recognizes this remnant of Haiti’s constitutional government.

All this is not without cost. Consider the kidnapping in November of Haitian-Dominican journalist Alexandre Galves. Haitian officials deny that Galves was taken on the Dominican side of the border—even though that’s almost certainly what happened and would constitute an act of war. Galves had unveiled corrupt details surrounding Haiti’s version of the Chavista influence-peddling (and politically compromising) cheap oil agreement run by Venezuela’s Cubans known as PetroCaribe—setting off the political crisis that preceded the current cycle of violence. As a pivotal actor in the opposition to the Moïse Administration’s reformist agenda, Galves’ disappearance gave credence to the increasingly obvious reality that Haiti is replacing Somalia as the world’s foremost example of anarchy.

The socialist and Brazilian-led pink tide of the 2000s, enforced through such stalwarts of the proletarian revolution as Cuba (a good example of illegitimate incidence in Haiti) are also present on the island on both sides of the border. Former Venezuelan intelligence chief Alex Saab is on the record testifying that Haiti is the best place in the world for arms trafficking, which is worrying, given his government’s link (again through oil) with an emerging axis has Nation of Islam black nationalists who have found their lodestar in the Haitian revolution. In teaming up with American Black Lives Matter activists (backstopped by the Congressional Black Caucus, no less), this coalition finds international expression in the Chinese-led Group of 77 (actually over 100 countries) whose bulk are the 54 African countries formally recognized by the United Nations.

There is a consistent ideological direction, and more dangerously one unfazed by the failure of the Haitian revolution to deliver abundance to the Haitian people (and answer arrogant princelings from middle kingdoms). Multiple forays into balkanization, monarchism and a French-inflected caudillismo generalize a through-line of lack of liberal self-government in all of Haitian history.

Foreign aggressions by Haiti include no less than seven invasions of its neighbor, which successfully repelled every attempt since its independence from Haiti’s domineering occupation between 1822 and 1844.

Sadly, Haiti has become a crossroads of the world of shadows, which cannot but end up being regarded in hindsight as a tinderbox waiting for a match. People in the region have some responsibility to plan for the future, including for the seemingly inevitable conflict between the major armed factions on Haitian territory—regardless of whose backing they have up to the point when the civil war finally sparks.

In Haiti, the refining of the art of throwing bad money after bad has reached levels hitherto unheard of. Haiti has no great mineral wealth or agricultural potential since disposing of its vegetation. No amount of sacrifice to the ideological golden calves of the Haitian revolution will ever be enough to make it work.

Despite this, U.S. Representative Greg Meeks (D-N.Y.) managed to send a letter signed by 70 members of Congress demanding a change of policy from the Trump-era status quo. The price is being paid by the Dominican Republic and other Caribbean countries, onto whom the international community often shunts responsibility for Haitian problems, despite their own challenges.

As the international order deteriorates, the truth will set you free only in the sense that inconvenient issues—such as the international community’s notorious failure to fix Haiti—are continually swept under the rug. It is as much a finger in the eye of elitist globalist ambitions as Brexit or the migration crises around the world, and it will stop recognizing Taiwan as the real China soon if we don’t restore order there.

Dust off your copy of The Black Jacobins for Haitian Independence Day on January 1. The world over should be commemorating in grief the 200th anniversary of the Haitian invasion and atrocities.

Being caught in the crossfire of Haiti’s hurricane of horrors has never been a good time or a good place to be. But Western civilization is under threat, and the island of Hispaniola must stand ready to hold the line once again. Perhaps, Haiti should be dismantled and allowed to start over. Using its indigenous voodoo, it might commence by casting a better spell on itself.

Theodore Roosevelt Malloch and Felipe Cuello are co-authors of Trump’s World: GEO DEUS. (This article appears courtesy of American Greatness).

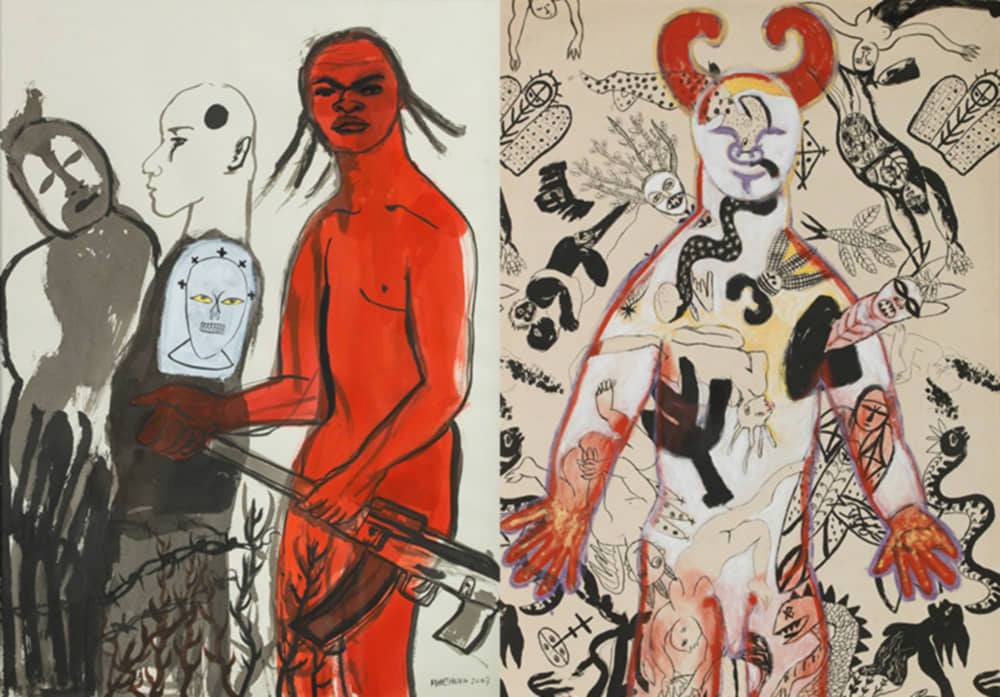

Featured image: a composition by Marie-Hélène Cauvin, 2007.