[In what follows, the views expressed are those of the author alone. The Postil does not advocate war with Russia, nor any other processes of “regime change.” We are publishing this article to show the consensus among Western conservatives who are against Russia. We are also publishing a refutation of this attitude.]

War is a messy business, and unless our national interest is at stake, we should avoid it as much as possible. But ‘national interest’ can mean many different things. It can mean that our national security is threatened, or that our economic well-being is at stake because the aggressor can put his hands on the natural resources that we need in a distant country. Here, it would seem, the list of what “our” national interest is ends. But does it really?

In America we often hear that we should support Israel “because Israel is the only democracy in the Middle East.” To say this is to say that in “our interest” is to support regimes which adopted similar political ideologies to ours. Accordingly, “our interest” is not always limited to our economic or security concerns but is occasionally propelled by ideological concerns. But ideology is not a shared cultural Weltanschauung. The latter notion explains why we support democratic Israel but are not supportive of democratic Iran.

The problem with shared ideological assumptions is that they are temporary (communist countries support other communist countries; liberal democracies support other liberal democracies; autocrats support other autocrats) whereas a Weltanschauung with religious origins is the heart of civilizations.

When Mr. Trump became president, he made his first trip to Saudi Arabia. On his way back home, he stopped in Israel where he told the leaders of the Jewish State, that he is coming from the Middle East! Well, it was a gaffe, which only a geographical ignoramus can make. However, what was a factual mistake (since both Saudi Arabia and Israel are in the Middle East) turns out to be a cultural truth. Israel is not a ‘normal’ Middle Eastern country; it is part of the West or Europe. If you have any doubts, here is the proof: the Israeli football (i.e., soccer) team plays in the European Football League, and this is not because the Muslims can’t kick the ball.

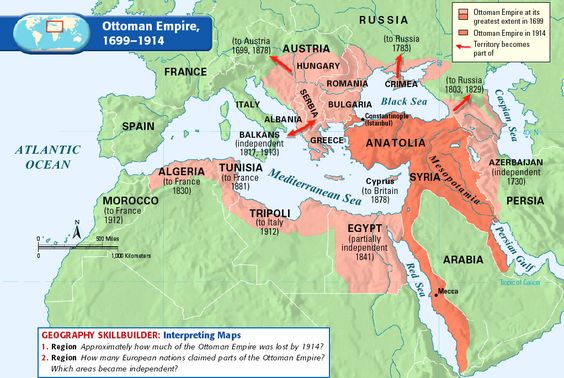

The question comes down to cultural roots of the West, which is the Christian religion with its Jewish Old Testament roots. The (Islamic) Ottoman Empire may have ruled over Greece, Macedonia, Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary, but all of them were Christian long before they had been conquered by the Turks. They belong to what we used to call in English Christendom (or the Res publica Christiana in Latin), the term which Winston Churchill still used during World War I in his letters to his wife.

To be sure, Res publica Christiana does not mean that only Christians inhabit the nominally Christian countries. It means that the Christian religion is the foundation of our cultural realm or dominion, our common law and even our morals and the way we behave. This dominion spreads from Rome, Lisbon, London, Warsaw, but also to San Francisco, Vancouver, New York, Mexico City and Buenos Aires, in South America, and Sidney or Melbourne in Australia. In eastern Europe it also includes Tallinn (Latvia), Vilnius (Lithuania), Riga (Estonia), and… Kyiv in Ukraine.

Values are what defines civilization. Whether the Israeli soccer players know about it or not, they are modern-day debtors to the Medieval crusaders who by embarking on the adventure to take the Holy Land from the hands of the Infidels, made the Promised Land part of the European mind. We do not know whether any adviser to Richard the Lion-Heart told him that it was not in the English ‘national interest’ to do go to war in a far away country. If such an argument had been used, the king must have rejected it in the name of common religious Weltanschauung. Centuries later Lord Byron, as many more Europeans, died fighting to free Greece from the Ottoman yoke.

Conservatives have always been uneasy about going to war in the name of planting the seeds of democracy elsewhere or liberating others so that they could adopt our way of life. And they were often right. Countries which do not share the same cultural assumptions are unlikely to be a fertile ground for such enterprise to succeed. The recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan prove their point.

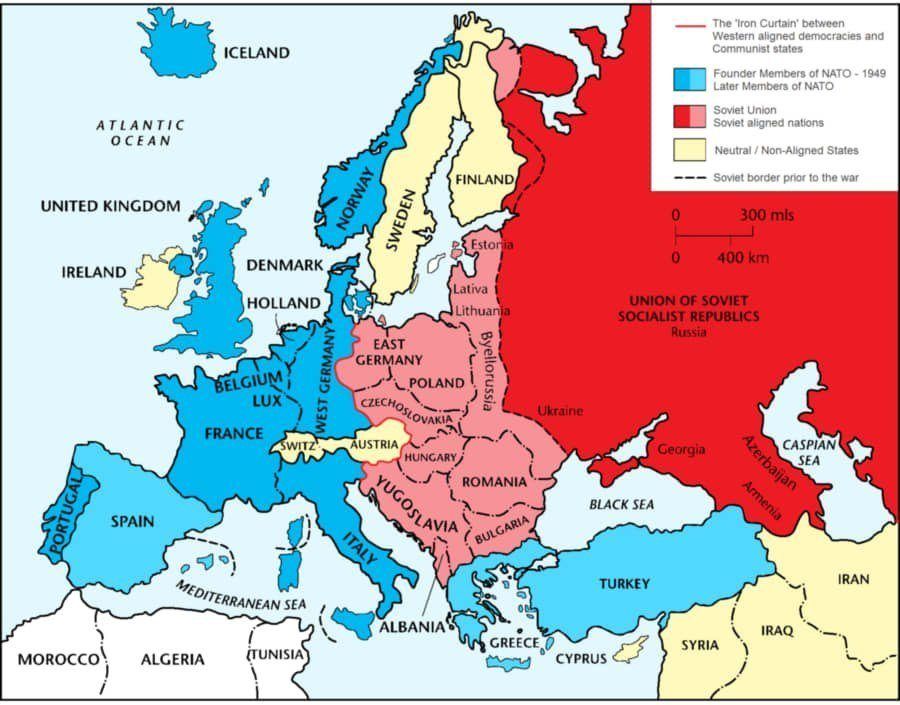

However, there is a difference between Afghanistan and Iraq, and the conservative bloggers, writers, journalists, and members of Congress who shout that engaging in the Ukraine’s affairs is not in our interest act as if they worked for Putin who does everything to convince the world Ukrainians are not a nation, that the Ukraine always was part of Russia, and those among Ukrainians who think differently (including President Zelensky) are neo-Nazis who must be eliminated. Both Ukraine and Russia were liberated from the yoke of Communism in 1991. However, the freedom they experienced was used differently by them. When Ukraine ceased to be part of the Soviet Union it understood that her place is in Europe. Russia, on the other hand, partly because of her history, partly because of the people who seized power after the collapse of the Soviet Union, was unable to find a new place in the world. Her autocratic and anti-Western tradition took over.

Putin’s anti-American obsession is of a cultural nature. As he said recently, Napoleon and Hitler subjugated Europe but Russia liberated it; America did the same by subjugating Europe using NATO, which is her military arm. In his view, the fight against American hegemony in Europe is at the same time a fight to liberate Europe from American tyranny. This is absurd, but such statements inscribe themselves well in the Russian way of viewing Russia’s destiny and her role in the world as Third Rome, the guardian of tradition

What conservatives need to understand is that their ignorance of which country belongs to Christendom does not change this country’s population’s cultural belonging and helping Ukraine is in the interest if keeping conservative values alive. Few 19th century politicians thought Greece, Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania were part of Europe. Like the countries that belonged to the Soviet bloc between 1945 and 1989 (Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania), so Greece, Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania had been part of the Muslim Ottoman Empire, and for this very reason they were not, in the eyes of many, part of the European political Ivy League. They were like students who had played hooky (or truant, as the British say) for over three hundred years of Turkish occupation and who missed the lessons of the Renaissance, 17th century Modernity, the Baroque, and the Enlightenment. Yet, even after centuries, they preserved Europe’s core values while the progressive West lost. All of them are members of European Union and were it not for them, the progressive “Ivy League” countries would not face any opposition in Brussels.

There are many reasons for American Right’s reluctance to support Ukraine. Partly, but only partly, it is the belief that as conservatives we should not impose our values on others or liberate anyone. The other is the Right’s admiration for strong man, which has roots in democracy’s deficit of authority, and consequently inability to uphold cultural values, except those which are created ad hoc. From this perspective, Putin may indeed even appear as the man who stands for something while the West’s defense of LGBTQ rights – which is the prism through which all social and political problems in the Western world are currently organized – is the source of cultural and moral malaise. Hence the Right’s query: should we go to war for the values which undermine the very foundation of our cultural tradition? Supporting the war means, the argument implies, to support the Left.

This is a series of problems that one should not disregard. However, accepting this position is to miss an important point. Putin and Russia do not represent Western Civilization, and if Putin happens to loath what Western conservatives loath too, it is because he is keenly aware that what passes for European values today is a form of poison that can be as corroding for Russia as it is for the West.

This is a scenario well-known from Dostoevsky’s novels: the confrontation between Mother Russia—the fountainhead of all that is good—and the corrupt West. There is a difference, however. Today’s Ivan Karamazov is not an atheist who in his rebellion refuses to accept God who created this world on the tears of a little girl tormented by her parents but a transgendered member of LGBTQ community who rebels against oppressive social structures that limit his sexual expression.

The question which everybody asks is: What, if anything, can be done about Putin and what can we do for Ukraine? In his most recent article “Joe Biden Has Only Days to Avoid Becoming Jimmy Carter” (February 27), Niall Ferguson wrote the following:

To avoid the fate of Carter, I believe Biden needs to go back further in time than 1979 and reflect on how Henry Kissinger handled a not dissimilar geopolitical crisis in October 1973, when a coalition of Arab states, led by Egypt and Syria, attacked Israel. (If your memory needs refreshing, I recommend Martin Indyk’s excellent new book on the subject.) Recall that Israel, like Ukraine today, was not a NATO member and could expect no support from the UN Security Council, not least because of the Soviet presence as a permanent member of that body.

At the risk of over-simplification, Kissinger’s approach can be summarized as follows. First, he ensured that Israel received U.S. military arms to the extent necessary to avert defeat, but not on such a scale that they could humiliate the Arabs. Second, he seized the diplomatic initiative, ensuring that any peace would be brokered by the US., with the Soviets effectively excluded. Third, Kissinger was himself willing to use a heightened nuclear alert to intimidate Moscow. These are precisely the things the Biden administration is not doing. Although the US has been arming Ukraine, the amounts involved — $60 million in the fall, $200 million in December and now a further $350 million — are not nearly enough to ensure the country survives the Russian onslaught. The amount needs to be at least tripled and the hardware needs to start arriving on Ukrainian soil in U.S. military aircraft, as it arrived in Israel in 1973, tomorrow. If Kyiv falls, the supplies to sustain Ukrainian resistance must continue.

This is a sound proposal, but as any proposal, it needs to be translated into action, and the action can be paralyzed by how we think of Russia and Putin. To stop the Russian onslaught, the Ukrainians need arms and fighter jets to stop the Russians from bombing their cities. The U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken put forth a sound proposal: to send to Ukraine Poland’s military Mig-29 jets, which later Poland would replace with American-made military aircraft. The proposal, it seems, is a sound one. However, only a few days later, a new problem arose. Poland did not think it should take responsibility for sending the planes directly to the Ukraine and suggested that they fly from the American military bases in Germany.

Why did Poland do this? So as not to appear (to Russia) as the only country responsible for the supply of the planes that would help the Ukrainians to fight Russian attacks. America, on the other hand, did not think of Poland’s proposal as a viable alternative since it could be seen by Russia as NATO’s involvement, which could have “far reaching consequences.” The problem with both positions is that they are based on the assumption that Putin’s reactions are symmetrical: if we do not do something, Putin will have no justification to respond.

Nothing could be further from truth. Everything that we know about Putin and learned in the last few weeks is that he does what he intended to do: “To make Russia great again” by regaining the territories lost after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Unless he is incapacitated, he will do everything to achieve his goal. If he intended to go to war with NATO, he will do it under another pretext than the supply of the Polish military aircrafts. He is already saying that the US and the West have waged economic war against Russia.

Putin may have said that the collapse of communism was the greatest 20th century’s calamity, but whatever he wants to recreate is not the Soviet Union. Rather, it is Putin’s dream of the old world in which Russia is an empire and he is its ruler. It is important to bear in mind that Putin’s empire is not an ideological state, and when it runs out of ideological fuel it will stop expending. Empires expand by the force of personal ambition of a monarch, an emperor, or a sultan. Individual autocrats step down only when they are forced to. Sending twenty fighter jets to support Ukrainian resistance is unlikely to cause WWIII, but if Russia is bogged down by the war, there is a chance it will cause unrest in Russia and Putin may be forced to step down.

As I stated at the very beginning: war is a messy business, and since this war was provoked by Russia, we have a chance to use it to our advantage. So far the war is not going well for Putin. Lack of military success and the sanctions imposed by the West are likely to have debilitating effects on Russia, its morale and economy. Russia’s failure in the Ukraine is important to America and the West for another reason, namely Taiwan which may soon become an object of China’s aggression. If Russia wins in the Ukraine, there is every reason to believe that China will be encouraged to do the same in Taiwan. If Russia loses, we should hope, it will have a sobering effect on China’s leaders who may come to the realization that attacking Taiwan is to play with fire. After all, no one wants to get burnt.

Zbigniew Janowski is the author of several books on 17th century philosophy and is editor of Leszek Kolakowski and J.S. Mill’s writings. His most recent book is Homo Americanus: The Rise of Totalitarian Democracy in America).