The arrogant sun had stalked away into the evening, trailing behind him banners of gold and crimson, and a swift twilight was streaming over the land. As the sun passed, the eyes of two men on a high hill followed it, and the look of one was like a light in a window to a lost traveller. It had in it the sense of home and the tale of a journey done. Such a journey this man had made as few have ever attempted, and fewer accomplished. To the farthermost regions of snow and ice, where the shoulder of a continent juts out into the northwestern Arctic seas, he had travelled on foot and alone, save for his dogs, and for Indian guides, who now and then shepherded him from point to point. The vast ice-hummocks had been his housing, pemmican, the raw flesh of fish, and even the fat and oil of seals had been his food. Ever and ever through long months the everlasting white glitter of the snow and ice, ever and ever the cold stars, the cloudless sky, the moon at full, or swung like a white sickle in the sky to warn him that his life must be mown like grass. At night to sleep in a bag of fur and wool, by day the steely wind, or the air shaking with a filmy powder of frost; while the illimitably distant sun made the tiny flakes sparkle like silver—a poudre day, when the face and hands are most like to be frozen, and all so still and white and passionless, yet aching with energy. Hundreds upon hundreds of miles that endless trail went winding to the farthest North-west. No human being had ever trod its lengths before, though Indians or a stray Hudson’s Bay Company man had made journeys over part of it during the years that have passed since Prince Rupert sent his adventurers to dot that northern land with posts and forts, and trace fine arteries of civilisation through the wastes.

Where this man had gone none other had been of white men from the Western lands, though from across the wide Pacific, from the Eastern world, adventurers and exiles had once visited what is now known as the Yukon Valley. So this man, browsing in the library of his grandfather, an Eastern scholar, had come to know; and for love of adventure, and because of the tale of a valley of gold and treasure to be had, and because he had been ruined by bad investments, he had made a journey like none ever essayed before. And on his way up to those regions, where the veil before the face of God is very thin and fine, and men’s hearts glow within them, where there was no oasis save the unguessed deposit of a great human dream that his soul could feel, the face of a girl had haunted him. Her voice—so sweet a voice that it rang like muffled silver in his ears, till, in the everlasting theatre of the Pole, the stars seemed to repeat it through millions of echoing hills, growing softer and softer as the frost hushed it to his ears-had said to him late and early, “You must come back with the swallows.” Then she had sung a song which had been like a fire in his heart, not alone because of the words of it, but because of the soul in her voice, and it had lain like a coverlet on his heart to keep it warm:

“Adieu! The sun goes awearily down,

The mist creeps up o’er the sleepy town,

The white sail bends to the shuddering mere,

And the reapers have reaped and the night is here.

Adieu! And the years are a broken song,

The right grows weak in the strife with wrong,

The lilies of love have a crimson stain,

And the old days never will come again.

Adieu! Where the mountains afar are dim

‘Neath the tremulous tread of the seraphim,

Shall not our querulous hearts prevail,

That have prayed for the peace of the Holy Grail.

Adieu! Sometime shall the veil between

The things that are and that might have been

Be folded back for our eyes to see,

And the meaning of all shall be clear to me.”It had been but an acquaintance of five days while he fitted out for his expedition, but in this brief time it had sunk deep into his mind that life was now a thing to cherish, and that he must indeed come back; though he had left England caring little if, in the peril and danger of his quest, he ever returned. He had been indifferent to his fate till he came to the Valley of the Saskatchewan, to the town lying at the foot of the maple hill beside the great northern stream, and saw the girl whose life was knit with the far north, whose mother’s heart was buried in the great wastes where Sir John Franklin’s expedition was lost; for her husband had been one of the ill-fated if not unhappy band of lovers of that civilisation for which they had risked all and lost all save immortality. Hither the two had come after he had been cast away on the icy plains, and as the settlement had crept north, had gone north with it, always on the outer edge of house and field, ever stepping northward. Here, with small income but high hearts and quiet souls, they had lived and laboured. And when this newcomer from the old land set his face northward to an unknown destination, the two women had prayed as the mother did in the old days when the daughter was but a babe at her knee, and it was not yet certain that Franklin and his men had been cast away for ever. Something in him, his great height, his strength of body, his clear, meditative eyes, his brave laugh, reminded her of him—her husband—who, like Sir Humphrey Gilbert, had said that it mattered little where men did their duty, since God was always near to take or leave as it was His will. When Bickersteth went, it was as though one they had known all their lives had passed; and the woman knew also that a new thought had been sown in her daughter’s mind, a new door opened in her heart.

And he had returned. He was now looking down into the valley where the village lay. Far, far over, two days’ march away, he could see the cluster of houses, and the glow of the sun on the tin spire of the little Mission Church where he had heard the girl and her mother sing, till the hearts of all were swept by feeling and ravished by the desire for “the peace of the Holy Grail.” The village was, in truth, but a day’s march away from him, but he was not alone, and the journey could not be hastened. Beside him, his eyes also upon the sunset and the village, was a man in a costume half-trapper, half-Indian, with bushy grey beard and massive frame, and a distant, sorrowful look, like that of one whose soul was tuned to past suffering. As he sat, his head sunk on his breast, his elbow resting on a stump of pine—the token of a progressive civilisation—his chin upon his hand, he looked like the figure of Moses made immortal by Michael Angelo. But his strength was not like that of the man beside him, who was thirty years younger. When he walked, it was as one who had no destination, who had no haven towards which to travel, who journeyed as one to whom the world is a wilderness, and one tent or one hut is the same as another, and none is home.

Like two ships meeting hull to hull on the wide seas, where a few miles of water will hide them from each other, whose ports are thousands of miles apart, whose courses are not the same, they two had met, the elder man, sick and worn, and near to death, in the poor hospitality of an Indian’s tepee. John Bickersteth had nursed the old man back to strength, and had brought him southward with him—a silent companion, who spoke in monosyllables, who had no conversation at all of the past, and little of the present; but who was a woodsman and an Arctic traveller of the most expert kind; who knew by instinct where the best places for shelter and for sleeping might be found; who never complained, and was wonderful with the dogs. Close as their association was, Bickersteth had felt concerning the other that his real self was in some other sphere or place towards which his mind was always turning, as though to bring it back.

Again and again had Bickersteth tried to get the old man to speak about the past, but he had been met by a dumb sort of look, a straining to understand. Once or twice the old man had taken his hands in both of his own, and gazed with painful eagerness into his face, as though trying to remember or to comprehend something that eluded him. Upon these occasions the old man’s eyes dropped tears in an apathetic quiet, which tortured Bickersteth beyond bearing. Just such a look he had seen in the eyes of a favourite dog when he had performed an operation on it to save its life—a reproachful, non-comprehending, loving gaze.

Bickersteth understood a little of the Chinook language, which is familiar to most Indian tribes, and he had learned that the Indians knew nothing exact concerning the old man; but rumours had passed from tribe to tribe that this white man had lived for ever in the farthest north among the Arctic tribes, and that he passed from people to people, disappearing into the untenanted wilderness, but reappearing again among stranger tribes, never resting, and as one always seeking what he could not find.

One thing had helped this old man in all his travels and sojourning. He had, as it seemed to the native people, a gift of the hands; for when they were sick, a few moments’ manipulation of his huge, quiet fingers vanquished pain. A few herbs he gave in tincture, and these also were praised; but it was a legend that when he was persuaded to lay on his hands and close his eyes, and with his fingers to “search for the pain and find it, and kill it,” he always prevailed. They believed that though his body was on earth his soul was with Manitou, and that it was his soul which came into him again, and gave the Great Spirit’s healing to the fingers. This had been the man’s safety through how many years—or how many generations—they did not know; for legends regarding the pilgrim had grown and were fostered by the medicine men who, by giving him great age and supernatural power, could, with more self-respect, apologise for their own incapacity.

So the years—how many it was impossible to tell, since he did not know or would not say—had gone on; and now, after ceaseless wandering, his face was turned towards that civilisation out of which he had come so long ago—or was it so long ago—one generation, or two, or ten? It seemed to Bickersteth at times as though it were ten, so strange, so unworldly was his companion. At first he thought that the man remembered more than he would appear to acknowledge, but he found that after a day or two everything that happened as they journeyed was also forgotten.

It was only visible things, or sounds, that appeared to open the doors of memory of the most recent happenings. These happenings, if not varied, were of critical moment, since, passing down from the land of unchanging ice and snow, they had come into March and April storms, and the perils of the rapids and the swollen floods of May. Now, in June, two years and a month since Bickersteth had gone into the wilds, they looked down upon the goal of one at least—of the younger man who had triumphed in his quest up in these wilds abandoned centuries ago.

With the joyous thought in his heart, that he had discovered anew one of the greatest gold-fields of the world, that a journey unparalleled had been accomplished, he turned towards his ancient companion, and a feeling of pity and human love enlarged within him. He, John Bickersteth, was going into a world again, where—as he believed—a happy fate awaited him; but what of this old man? He had brought him out of the wilds, out of the unknown—was he only taking him into the unknown again? Were there friends, any friends anywhere in the world waiting for him? He called himself by no name, he said he had no name. Whence came he? Of whom? Whither was he wending now? Bickersteth had thought of the problem often, and he had no answer for it save that he must be taken care of, if not by others, then by himself; for the old man had saved him from drowning; had also saved him from an awful death on a March day when he fell into a great hole and was knocked insensible in the drifting snow; had saved him from brooding on himself—the beginning of madness—by compelling him to think for another. And sometimes, as he had looked at the old man, his imagination had caught the spirit of the legend of the Indians, and he had cried out, “O soul, come back and give him memory—give him back his memory, Manitou the mighty!”

Looking on the old man now, an impulse seized him. “Dear old man,” he said, speaking as one speaks to a child that cannot understand, “you shall never want, while I have a penny, or have head or hands to work. But is there no one that you care for or that cares for you, that you remember, or that remembers you?”

The old man shook his head though not with understanding, and he laid a hand on the young man’s shoulder, and whispered:

“Once it was always snow, but now it is green, the land. I have seen it—I have seen it once.” His shaggy eyebrows gathered over, his eyes searched, searched the face of John Bickersteth. “Once, so long ago—I cannot think,” he added helplessly.

“Dear old man,” Bickersteth said gently, knowing he would not wholly comprehend, “I am going to ask her—Alice—to marry me, and if she does, she will help look after you, too. Neither of us would have been here without the other, dear old man, and we shall not be separated. Whoever you are, you are a gentleman, and you might have been my father or hers—or hers.”

He stopped suddenly. A thought had flashed through his mind, a thought which stunned him, which passed like some powerful current through his veins, shocked him, then gave him a palpitating life. It was a wild thought, but yet why not—why not? There was the chance, the faint, far-off chance. He caught the old man by the shoulders, and looked him in the eyes, scanned his features, pushed back the hair from the rugged forehead.

“Dear old man,” he said, his voice shaking, “do you know what I’m thinking? I’m thinking that you may be of those who went out to the Arctic Sea with Sir John Franklin—with Sir John Franklin, you understand. Did you know Sir John Franklin—is it true, dear old boy, is it true? Are you one that has lived to tell the tale? Did you know Sir John Franklin—is it—tell me, is it true?”

He let go the old man’s shoulders, for over the face of the other there had passed a change. It was strained and tense. The hands were outstretched, the eyes were staring straight into the west and the coming night.

“It is—it is—that’s it!” cried Bickersteth. “That’s it—love o’ God, that’s it! Sir John Franklin—Sir John Franklin, and all the brave lads that died up there! You remember the ship—the Arctic Sea—the ice-fields, and Franklin—you remember him? Dear old man, say you remember Franklin?”

The thing had seized him. Conviction was upon him, and he watched the other’s anguished face with anguish and excitement in his own. But—but it might be, it might be her father—the eyes, the forehead are like hers; the hands, the long hands, the pointed fingers. “Come, tell me, did you have a wife and child, and were they both called Alice—do you remember? Franklin—Alice! Do you remember?”

The other got slowly to his feet, his arms outstretched, the look in his face changing, understanding struggling for its place, memory fighting for its own, the soul contending for its mastery.

“Franklin—Alice—the snow,” he said confusedly, and sank down.

“God have mercy!” cried Bickersteth, as he caught the swaying body, and laid it upon the ground. “He was there—almost.”

He settled the old man against the great pine stump and chafed his hands. “Man, dear man, if you belong to her—if you do, can’t you see what it will mean to me? She can’t say no to me then. But if it’s true, you’ll belong to England and to all the world, too, and you’ll have fame everlasting. I’ll have gold for her and for you, and for your Alice, too, poor old boy. Wake up now and remember if you are Luke Allingham who went with Franklin to the silent seas of the Pole. If it’s you, really you, what wonder you lost your memory! You saw them all die, Franklin and all, die there in the snow, with all the white world round them. If you were there, what a travel you have had, what strange things you have seen! Where the world is loneliest, God lives most. If you get close to the heart of things, it’s no marvel you forgot what you were, or where you came from; because it didn’t matter; you knew that you were only one of thousands of millions who have come and gone, that make up the soul of things, that make the pulses of the universe beat. That’s it, dear old man. The universe would die, if it weren’t for the souls that leave this world and fill it with life. Wake up! Wake up, Allingham, and tell us where you’ve been and what you’ve seen.”

He did not labour in vain. Slowly consciousness came back, and the grey eyes opened wide, the lips smiled faintly under the bushy beard; but Bickersteth saw that the look in the face was much the same as it had been before. The struggle had been too great, the fight for the other lost self had exhausted him, mind and body, and only a deep obliquity and a great weariness filled the countenance. He had come back to the verge, he had almost again discovered himself; but the opening door had shut fast suddenly, and he was back again in the night, the incompanionable night of forgetfulness.

Bickersteth saw that the travail and strife had drained life and energy, and that he must not press the mind and vitality of this exile of time and the unknown too far. He felt that when the next test came the old man would either break completely, and sink down into another and everlasting forgetfulness, or tear away forever the veil between himself and his past, and emerge into a long-lost life. His strength must be shepherded, and he must be kept quiet and undisturbed until they came to the town yonder in the valley, over which the night was slowly settling down. There two women waited, the two Alices, from both of whom had gone lovers into the North. The daughter was living over again in her young love the pangs of suspense through which her mother had passed. Two years since Bickersteth had gone, and not a sign!

Yet, if the girl had looked from her bedroom window, this Friday night, she would have seen on the far hill a sign; for there burned a fire beside which sat two travellers who had come from the uttermost limits of snow. But as the fire burned—a beacon to her heart if she had but known it—she went to her bed, the words of a song she had sung at choir—practice with tears in her voice and in her heart ringing in her ears. A concert was to be held after the service on the coming Sunday night, at which there was to be a collection for funds to build another mission-house a hundred miles farther North, and she had been practising music she was to sing. Her mother had been an amateur singer of great power, and she was renewing her mother’s gift in a voice behind which lay a hidden sorrow. As she cried herself to sleep the words of the song which had moved her kept ringing in her ears and echoing in her heart:

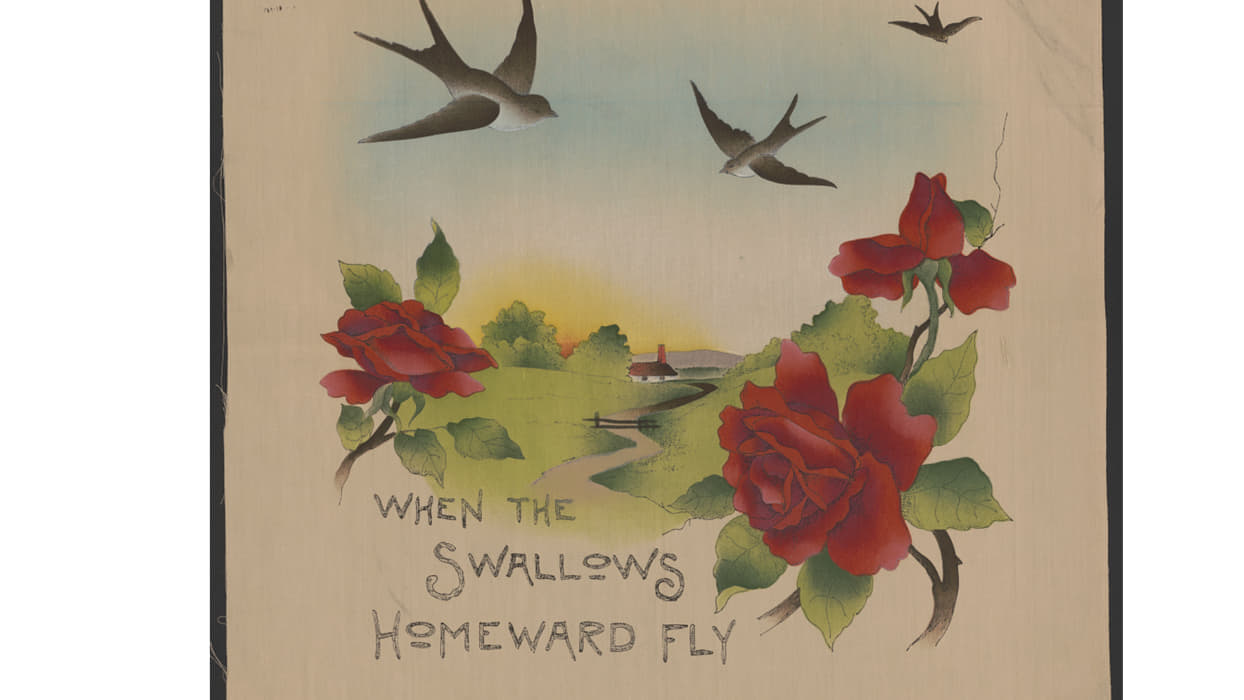

“When the swallows homeward fly,

And the roses’ bloom is o’er—”But her mother, looking out into the night, saw on the far hill the fire, burning like a star, where she had never seen a fire set before, and a hope shot into her heart for her daughter—a hope that had flamed up and died down so often during the past year. Yet she had fanned with heartening words every such glimmer of hope when it came, and now she went to bed saying, “Perhaps he will come to-morrow.” In her mind, too, rang the words of the song which had ravished her ears that night, the song she had sung the night before her own husband, Luke Allingham, had gone with Franklin to the Polar seas:

“When the swallows homeward fly—”

As she and her daughter entered the little church on the Sunday evening, two men came over the prairie slowly towards the town, and both raised their heads to the sound of the church-bell calling to prayer. In the eyes of the younger man there was a look which has come to many in this world returning from hard enterprise and great dangers, to the familiar streets, the friendly faces of men of their kin and clan-to the lights of home.

The face of the older man, however, had another look.

It was such a look as is seldom seen in the faces of men, for it showed the struggle of a soul to regain its identity. The words which the old man had uttered in response to Bickersteth’s appeal before he fainted away, “Franklin—Alice—the snow,” had showed that he was on the verge; the bells of the church pealing in the summer air brought him near it once again. How many years had gone since he had heard church-bells? Bickersteth, gazing at him in eager scrutiny, wondered if, after all, he might be mistaken about him. But no, this man had never been born and bred in the far North. His was a type which belonged to the civilisation from which he himself had come. There would soon be the test of it all. Yet he shuddered, too, to think what might happen if it was all true, and discovery or reunion should shake to the centre the very life of the two long-parted ones.

He saw the look of perplexed pain and joy at once in the face of the old man, but he said nothing, and he was almost glad when the bell stopped. The old man turned to him.

“What is it?” he asked. “I remember—” but he stopped suddenly, shaking his head.

An hour later, cleared of the dust of travel, the two walked slowly towards the church from the little tavern where they were lodged. The service was now over, but the concert had begun. The church was full, and there were people in the porch; but these made way for the two strangers; and, as Bickersteth was recognised by two or three present, place was found for them. Inside, the old man stared round him in a confused and troubled way, but his motions were quiet and abstracted and he looked like some old viking, his workaday life done, come to pray ere he went hence forever. They had entered in a pause in the concert, but now two ladies came forward to the chancel steps, and one with her hands clasped before her, began to sing:

“When the swallows homeward fly,

And the roses’ bloom is o’er,

And the nightingale’s sweet song

In the woods is heard no more—”It was Alice—Alice the daughter—and presently the mother, the other Alice, joined in the refrain. At sight of them Bickersteth’s eyes had filled, not with tears, but with a cloud of feeling, so that he went blind. There she was, the girl he loved. Her voice was ringing in his ears. In his own joy for one instant he had forgotten the old man beside him, and the great test that was now upon him. He turned quickly, however, as the old man got to his feet. For an instant the lost exile of the North stood as though transfixed. The blood slowly drained from his face, and in his eyes was an agony of struggle and desire. For a moment an awful confusion had the mastery, and then suddenly a clear light broke into his eyes, his face flushed healthily and shone, his arms went up, and there rang in his ears the words:

“Then I think with bitter pain,

Shall we ever meet again?

When the swallows homeward fly—”“Alice—Alice!” he called, and tottered forward up the aisle, followed by John Bickersteth.

“Alice, I have come back!” he cried again.

1909.

The title of this story comes from a very popular German poem, “Wenn die Schwalben heimwärts ziehn,” from 1830, written by Karl Herlosssohn (1804-1849). The verse was set to music in 1849 by Franz Wilhelm Abt (1819-1885) and immediately became popular in Germany and the English-speaking world. It remains popular in Germany as a folksong.

Sir Gilbert Parker (1862 – 1932) was a Canadian writer and British parliamentarian. His stories are evocative of the early history of Canada, especially that of Quebec.

Featured: Chromolithograph print, from 1907.