The French traditionalist philosopher René Guénon wrote in his Crisis of the Modern World that the craving for the material is an inherent feature of modern Western civilization. The need for endless activity, the pursuit of the material, the desire to keep up with the accelerating rhythm of everyday life have replaced tradition; that is, the awareness of human life through a higher principle that goes beyond the material understanding of life. The philosophy of rationalism, empiricism, and positivism, on which the modern understanding of things rests, recognizes only knowledge gained by contact with matter, and religion and metaphysics as “obsolete” worldviews that have no place in a world of nonstop progress.

Philosophy that emerges in the modern age inverts man’s understanding of life, literally from top to bottom. If in primordial (i.e., traditional, according to Guénon) society and then in Christian (medieval) society the vertical model of awareness of reality prevailed—God is the Absolute, who orders life on earth—then, starting in the 17th century, man becomes the measure of all things, and he defines existence for himself. In the new, materialistic world, truth does not lie in a higher principle, but is the result of the thinking of the individual person. Society, philosophy, and politics are not built according to “God’s will,” but according to human thinking.

In this context, Nietzsche’s words become clear: “God is dead. And we killed him.” This means that the modern philosophical paradigm has put in the place of God—the Antichrist, embodied in the unstoppable pursuit of progress and the immutability of material values of Western European civilization, which carried out a rebellion against God.

In the nineteenth century, when Nietzsche lived, the intensification of industrialization and the flowering of capitalism led to an even greater dependence on money and a rejection of traditional values. The expansion of cities and total resettlement severed the of families to their homeland, leading to a loss of intergenerational understanding. Along with the dominance of money came economic doctrines: free trade and Marxism, according to which economic relations are the fundamental principle of building society; and culture, religion and even politics are secondary elements. The new belief in the materialistic sciences began to prevail over the belief in God. The will to accumulate monetary wealth overcame the will to be spiritual.

In the early twentieth century, the conservative philosopher Oswald Spengler, in his voluminous work The Decline of West, expressed the idea that Western civilization had entered its last cycle. He understood the crisis of the Western world as the problem of civilization, which is the final stage in the development of culture. “Civilizations are the most extreme and most artificial states to which only man of the highest kind is capable.” Thus, Spengler declared that Western culture has disappeared qualitatively and had reincarnated into a civilization that rests on the power of materialism and progress.

It can be said that the three above-mentioned philosophers—Nietzsche, Guénon and Spengler—articulated the state of decline of their modern world, which in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was artistically felt by many writers and poets. Some members of the creative intelligentsia responded sharply to the challenges of the material world; in their work, they not only spoke caustically about the problems of the new world order, but also called for a return to the deep roots of tradition.

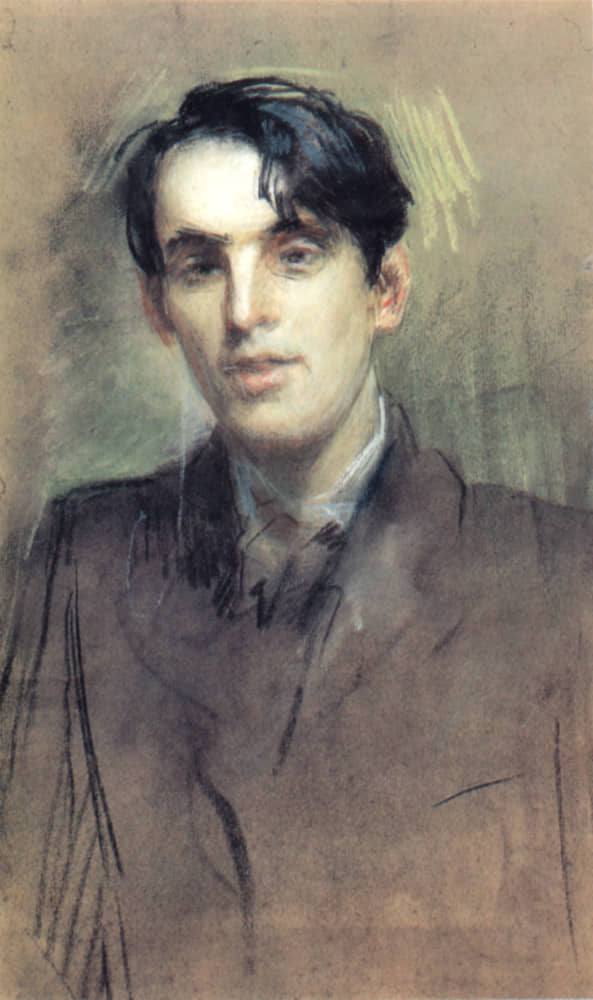

One of the poets who “rebelled” against the modern world was the leader of the Irish literary revival, W. B. Yeats. In many ways his creative path was shaped by his interest in mysticism and esotericism and his refusal to accept material temptations as the basis of life.

Yeats was born in 1865, at a time when Ireland was sharply contrasting its metaphysical, popular spirit with the imperial and colonial ambitions of England, which was expanding its presence in many parts of the world. The imperative of modernity, industrial revolution and progress, imposed by England, was alien to “a society dominated by Celtic archaicism.” Against this background, a particular Irish way began to develop assertively, which combined folk identity and the Celtic spirit, created not by artificial simulacra of modernity, but taking its origin in the traditions and legends of old Ireland.

Thus, from an early age, Yeats moved in the circles of writers and artists who introduced him to the ancient Irish myths and instilled in him a love of his Celtic roots. The future poet became aware early on of his soil-based identity, which eventually became a defining factor in his later work. At the age of 20, Yeats was no longer shy about identifying himself with soil-oriented movements. The young writer joined the “Young Ireland” movement, and then in his poetry there appeared a national motif, expressed in praise of Irish rebellion and a negative attitude, above all, to modern England.

Young Ireland’s Sovereignism was based on a hatred of British utilitarianism and a desire for global subjugation of the indigenous peoples of other countries. Political and cultural liberation from the dictates of England was seen as setting the stage for a deeper transformation of Irish society and the end of the cycle of decline. It is important to note that for Yeats the revolt against British colonialism was based not on the enthusiastic possibility of building a “nation-state,” which is also a bourgeois construct, but primarily on the principles of Irish cultural revival, based on its mythology, history and Tradition.

His understanding of the historical context and cultural decline of Ireland motivated him to write, for example, such a poem as “The Curse of Cromwell.” Oliver Cromwell’s revolution, as well as subsequent revolutions in Europe (and Russia), marked the triumph of materialism over spirit and tradition. Modern English society was founded on a puritanical money ethic that spread to other parts of the world as well. This was unacceptable to Yeats and his circle. They believed that a small, soil-based and anti-bourgeois Ireland should stand up to the Protestant and capitalist sedition that had spread its stench across Europe:

You ask what—I have found, and far and wide I go:

Nothing but Cromwell’s house and Cromwell’s murderous crew,

The lovers and the dancers are beaten into the clay,

And the tall men and the swordsmen and the horsemen, where are they?

And there is an old beggar wandering in his pride—

His fathers served their fathers before Christ was crucified.

O what of that, O what of that,

What is there left to say?

This is how the poet conveys his idea that English modern society, which has established its materialistic one-man rule, has destroyed the tradition and “chivalrous” spirit of old England. There were no more people of noble tradition, no more “high men;” the old-time cheerfulness of the peasant village, the squire’s manor and the aristocrat’s estate were destroyed.

In many ways, of course, Yeats’s soil and traditionalism stemmed from the poet’s interest in religion. As a teenager, he sensed that poetry and artistic culture in general were fueled by signs, symbols, and a strange magical mystery that had no place in the material world. But the soulless scientific materialism of the nineteenth century—the Darwinist theory of human evolution, the discovery by scientists of the age of the earth, etc.—deadened belief in the divine, as well as ancient knowledge in alchemy, the mysteries of numbers, and metaphysics.

Yeats saw that official Christianity—Irish Catholicism and English Protestantism—were driven into the conventions of the new materialist era. He rejected Protestantism as totally unorthodox and alien. His contemporary Catholicism also had nothing in common with the sacraments, rites and Christian mysticism. Insisting on intuitive spiritual truths inaccessible to the philistine worldview, he set out in search of a secret, symbolically expressed wisdom which he thought might be common to the world’s various orthodox and unorthodox religious traditions.

It is telling that Yeats’ understanding of the foundations of Christianity and any religion is similar to that of traditionalist philosophers, such as René Guénon. For Guénon, the fact of being introduced to Tradition is important; he points out that Tradition (the philosopher intentionally capitalizes this word) is a special reality, a special language, which is opposed to the reality of the modern world. Guénon structured a “skeleton” of Tradition that precedes “the formulation of a particular Tradition in its historically fixable incarnation.” In other words, there is one truth that is embodied differently in one particular tradition or another.

An interest in Tradition with a capital letter led Yeats to a fascination with mystical movements and organizations practicing hermeticism and studying the sacred sciences. In 1897, Yates moved to London and joined the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, which was a major influence in the revival of interest in metaphysics in England.

Yeats saw in the metaphysical and the spiritual a basic unity for all manifestations of culture and Tradition, which was embodied in the magical original: “I believe in the practice and philosophy of what we have agreed to call magic, in what I must call the evocation of spirits, though I do not know what they are, in the power of creating magical illusions, in the visions of truth in the depths of the mind when the eyes are closed.”

Human wisdom, divine revelation, and truth exist in all people of Tradition simultaneously, flowing from one mind into another, and revealed in one mind, in one energy. Let us compare this with what Guénon wrote: “In traditional civilization, it is almost impossible for a person to attribute an idea exclusively to himself… If an idea is true, it belongs to all who are able to comprehend it… A true idea cannot be ‘new,’ since truth is not a product of the human mind.”

Guénon was born 20 years after Yeats, but they worked and wrote around the same time. There is no evidence that Yeats was acquainted with the writings of Guénon , but it is surprising that two men who lived in different parts of the world—Yeats in England and Ireland, Gaenon (mostly) in Egypt—discovered the same truth of Tradition.

Guénon devoted part of his life to the study of the Hindu tradition. And it is significant that Yeats also studied Hindu philosophy with the theosophist Mohini Chatterjee, and joined the Theosophical Society in 1895. However, after the formation of the Irish Hermetic Order, the poet decided to devote himself to the study of the spiritual basis of Celtic culture and mythology, as a devoted son of his fatherland.

In 1931, no longer a young man, he met the Hindu preacher Sri Purohit Swami and again immersed himself in Hinduism. This second period of interest in Hindu mysticism replaced the romantic fascination of the early period with a much more active personal quest, accompanied by public apologetics for Eastern esotericism. Thus, despite his individual artistic path, Yeats had many points of contact with the founder of the philosophy of traditionalism and the chief critic of the modern world, René Guénon.

It should be noted that Yeats’s interest in Hinduism was more a strongly orientalized version of traditionalism rather than a complete immersion in the Hindu tradition, because his knowledge was gained at a considerable distance from India. Yeats’s study of Celtic archaicism, Hindu mysticism, or metaphysics are manifestations of a common truth that is revealed through the study of either tradition or religion.

Traditionalism opened to the poet a special understanding of the world and a vision of things. Yeats was characterized by a cyclical vision of history. In accordance with the Celtic tradition, he believed that “a complete cycle takes place within two millennia, and on this basis he linked the new stage of Irish liberation and rebirth with the more global processes—the end of the old aeon and the beginning of the new.” The philosopher Alexander Dugin uses the word “aeon” here not by chance—the cycles of time are characteristic of both European traditions and Hindu cosmology (where the term is taken from).

Guénon, describing Hindu teachings, claimed that the human cycle is divided into four epochs, during which primordial spirituality becomes more and more obscured. Currently, humanity is at the darkest point of the last cycle, Kali Yuga. And we have been in the “Dark Age” for six millennia; that is, since time older than known to history. According to Hindu doctrine, the end of the cycle will prove to be the beginning of a new cycle, when primordial Tradition will once again become true for all.

The cyclicality described in Hindu cosmology has common features with Christian eschatology described in the Revelation of John the Evangelist—the end of the world will come when the Antichrist will be born on earth and the wrath of God will fall on humanity.

After that Jesus Christ will appear and establish His kingdom forever. The Apostolic interpretation of the end of the world has the same structure as any Tradition—the end of the old, dark world and the beginning of the new world of light.

The theme of the Apocalypse is vividly reflected in Yeats’s poem, “The Second Coming.” In it, the poet combines all the major themes of his work—the decline of Western European culture (“Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world”), the loss of its spiritual core (“Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold”), the appeal to the mystical World Soul (“Spiritus Mundi”), the antagonism between the kingdom of the Antichrist, the world of modernity, and the Kingdom of Christ, the world of Tradition (“The best lack all conviction, while the worst/ Are full of passionate intensity”).

It is quite clear that the poet prophesies the appearance of a certain eschatological monster that will emerge from the chaos of the modern world, with its craving for the material, the denial of traditional values and the absolute of destructive progress:

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

It is interesting that in his poetry (as seen in this example) Yeats uses modernist literary devices, such as allusions to literary monuments and biblical motifs to describe modernity. The modernist techniques in Yeats’s work are symptomatic, but he can be classified as a modernist only in form, not in content. “Yeats was immersed in modernity only in part—to the extent of his engagement with English culture and English society… but at the same time his cultural identity was rooted in the traditional society that prevailed in Ireland until very recently.”

Recall also that the cyclical nature of the times—from dark to light and from light to dark—is found in Spengler: “Birth contains death, youth contains old age, life as such contains its image and its predetermined limits of duration. Modernity is a civilized and not at all a civilized age.” However, this “Spenglerian” (and at the same time ” Guénonian”) theme in Yeats’s poem takes into account not only the demise of civilization, but also the time cycle, where a new king (Jesus Christ) emerges from a decadent era to begin the rebirth of culture.

Like Spengler and Guénon, Yeats saw meaning and hope in emerging “hermetic” societies, as well as right-wing movements that promised to revive the world of Tradition and oppose their politics to the unstoppable machine of progress and money. The poet’s entire oeuvre is permeated with warnings about the perniciousness of modernity and the banality of the material world. Ultimately, though, Yeats, like any traditionalist, anticipated that the crisis of the modern world would inevitably lead to the final destruction of civilization, and he was prepared for the coming of the Antichrist so that he could subsequently cross the threshold and find himself in a new cycle of a renewed world. This belief did not leave him until the end of his creative journey, even when there were hardly any like-minded people left. Hence Yeats was honorably called “the last knight of Tradition” in the Irish literary canon.

Pavel Kiselev is a Russian literary critic. His work appears in Katehon, to whose generous courtesy we owe this essay.

Featured image: Portrait of William Butler Yeats, by Sarah Purser; painted in June 1898.