Now that the disgraceful year 2020 is finally gone, with its endless stream of deaths and grievance, we can properly look at what it brought us (Covid, lockdown, unemployment, etc.) and also what it stole from us. I firmly believe that like health and food, culture too is an essential nourishment for our lives, and any time we are deprived of it, we feel miserable and sick.

In Italy two great cultural events had been set for 2020 that were either cancelled or went unnoticed: the 500th anniversary of the death of Raphael Sanzio, and the introduction of Dante Day (Dante Dì), the official day to celebrate the immortal creator of the Divine Comedy. Yes, you read that right – until last year, in Italy, there was no official day to celebrate Italy’s greatest poet, and arguably one the greatest poet of all time.

The official dates were the 6th of April to celebrate the anniversary of Raphael, and the 25th of March to remember Dante. Now, these dates were very interesting because both men, by a surprising coincidence, have a connection to Good Friday. According to Giorgio Vasari’s Lives, Raphael was born on the night of Good Friday March 28, 1483 and died on Good Friday April 6, 1520. What an amazing coincidence for a man whose family name was Santi (Saints), which was then latinized into Sancti, and from this to the current Sanzio. And of course, almost all scholars agree that Dante began his fictitious travel into the Three Realms on Good Friday March 25 of the jubilee year 1300. Luckily enough, the official Italian committee discarded the death date of the bard on September 14 because it did not fit properly into the school time calendar. Sometimes obtuse bureaucracy helps!

As for the Raphael celebration, the best painting exhibition ever, collecting the greatest works of the master from museums all over the world, was organized in Rome at the Quirinal Palace. But, alas, it opened just few days before the first Covid outburst and was then sadly shut down a couple of weeks later in the midst of the first terrible stint of the pandemic in Italy. There will not be a second chance for this gorgeous Raphael show.

For Dante Day plenty of cultural events were planned involving scholars, school students, TV actors and ordinary citizens. Readings from the Divine Comedy should have taken place in the most iconic Italian piazze, where schools were invited to feature exhibitions on Dante, and TV was expected to provide huge coverage of the widespread festivities.

All these events were simply obliterated by the surging of the pandemic. In the only event downsized permitted, single citizens were invited to recite, from their windows or balconies, a few tercets of “Paolo and Francesca,” all together at 6:00 PM on March 25. I did that, and posted the recording to social media – and found out that the anniversary was not that popular among my connections. Never mind, next year marks the 700th anniversary of the death of Dante and luckily enough Covid 19 will give us a break by September 14.

But it is not only the sheer coincidence of calendar dates that links these two undisputed geniuses – men of different centuries, genuine children of their time and culture, with very different characters. But both also contributed immensely to elevate our poor humanity towards the perception and appreciation of divinity.

Raphael is unanimously considered the peak of Renaissance painting, capable of shifting Leonardo’s sfumato technique into astonishingly natural and beautiful reality. If ever the Italian Renaissance has meant grace, beauty, harmony, naturality, Raphael is the true and complete achievement of it. Just imagine, from the moment he died in 1520 until the Impressionist revolution in the mid-19th century, his work was the inspiration and touchstone for all painting academies in all countries of the western world. His cycle of Madonna and child Jesus simply set forever the iconographic standard for this holy representation, and you can find a copy of one of them in almost any Italian Christian home. But Raphael is also the creator of the Stanze di Raffaello (the Raphael Rooms), where he mastered his refined art into a theological and compositional complexity that attained unequalled heights in the history of art.

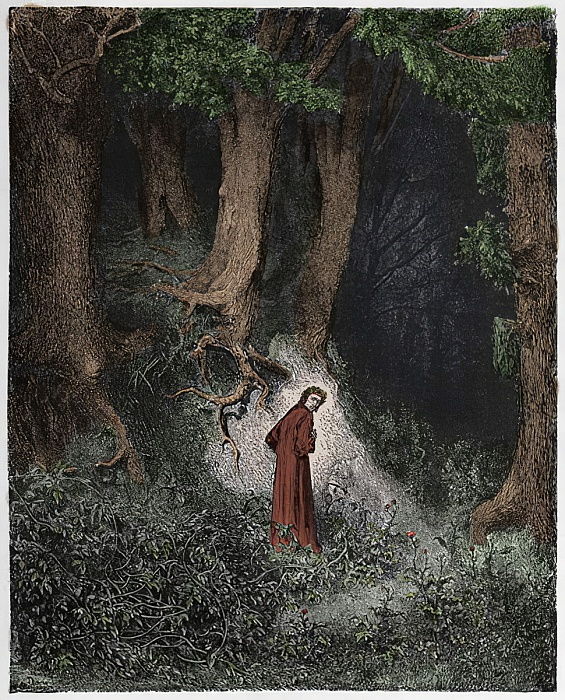

Raphael was a good Christian, and this must not be taken for grant, even in the pope-ruled Rome of the early 16th century. The story goes that on Good Friday 1520, sensing his end, Raphael asked that his last masterpiece, The Transfiguration, be brought into his room and hung on the wall in front of him. There is no doubt about the reason – looking at the beautiful radiant Christ, he was already savouring the glory of his encounter with Him. When you survey the entirety of western Christian figurative production, it is hard to find as glorious and serene an image of the defeat of death, of which The Transfiguration is both a pledge and promise.

I do not know Raphael’s biography so well as to appraise the depth of his religious feeling and belief. However, it is unquestionable that the Holy Spirit guided his hand and heart in the short span of his life.

Unveiling the presence of divinity in Dante is a much easier job, starting from the very title of his masterpiece The Comedy soon after labelled as Divine by his great contemporary, Giovanni Boccaccio, partially because of the theme of the composition but mostly for the unrivalled poetic heights the work accomplished. Some passages warmed our youthful reading (“Paolo and Francesca,” “the voyage of Ulysses,” “Count Ugolino,” and the “Hymn to the Virgin”), others led and transformed our mature-years through a more Christian and mediated reading of Purgatory and Paradise canticles.

And we really do not care if, in praising the institution of Dante Day, the complete host of Italian intelligentsia saluted “The Father of the Italian Language,” “The very first Italian,” and “The founder of European identity.” For us he will be forever the poet who amazingly translated the truths of our faith into exultations of the heart and tears of love: “l’amor che muove il sole e l’altre stelle.” The work of Dante is always so divinely inspired and filled with poetical miracles that he deserves to stay on the calendar regardless of a questionable civil beatification. In this terrible pandemic times we all, we believers first, should start back from where he commenced his journey: “Miserere di me”.

God is a loving Father and an excellent Teacher; He can use many different ways to show us the path to paradise. Among them all, the human longing for beauty sublimely initiates our earthly journey to the glory of celestial infinity. Bless Him for spreading our road with so many friendly and inspiring companions!

Maurizio Mandelli is a businessman by trade and enthusiastic amateur scholar of local history and the arts. He has published two books (War of the Spanish Succession in Lombardy and The Italian Campaign of Napoleon III). He is a regular contributor to local magazines on religion, ethics, society, history and the arts.

The image shows, “The Transfiguration,” by Raphael, painted ca. 1518-1520.