“Hey, Hey, Ho, Ho, Western Civ Has Got to Go …” (Jessi Jackson, Stanford University, January 15, 1987).

Defending Classical education, or the Classics, is not easy. Many attempts have been made, but they were rather unsuccessful. Even the best arguments of distinguished classicists and scholars of Antiquity sound like desperate plea for survival. One can also wonder why it is only the classicists who defend their discipline. One does not hear, for example, the Medieval or Renaissance scholars weeping over lack of interest in their periods, and low enrollment in their courses.

One explanation is that they know that as important as the knowledge of their historical period is, their epoch is a closed chapter, and the ideas those periods generated have little significance for our lives. This does not seem to be the case with the Classics, particularly the Greeks. Their world is, or that is what the Classicists believe, as important today as it was over two thousand years ago.

Before I explain why Classical education is important and why it died, or is dying, let me briefly recount a few historical facts. If one looks at the history of roughly six centuries in the West, the Classics had many moments of good fortune.

The first was the Renaissance, the epoch which resurrected Classical or Greco-Roman antiquity, and whose literal definition is “Rebirth.” It was a rebirth of the Greco-Roman world, the world whose institutional structures collapsed in 476 AD. However, the Renaissance was not only a rebirth. It was also the time in Western history when, after almost a thousand years, Europe achieved a comparable level of cultural development which we find in the late Roman Empire.

The 17th-century was by no means a continuation of the Renaissance. Despite the fact that 17th-century thinkers attacked the ancients, 17th century was a classical age par excellence. It was an “age of eloquence”; an age of French theatre, of Corneille and Racine, who applied strict classical rules in their plays and rhetoric. Were it not for the genius of Shakespeare, who broke those rules, the ancients would have been indisputable winners in this contest. Painters (Paul Rubens, Nicholas Poussin, Claude Lorraine, and many others) made Greece and Rome the subject of their many works.

The 18th-century was different, but equally lucky. Rome seized the imagination of the artists, major and minor. One can easily discern Classical motives in Baroque and Rococo ornaments. Giuseppe Vasi was obsessed with antiquity, just like his student, Giovani Baptista Piranesi. He was particularly taken by Rome; so were his successors Luigi Rossini and Gabriele Ricciardelli. Those who are lovers of Roman antiquity cannot free themselves from the memory of the dark ink dripping from Piranesi and Rossini’s engravings.

Late 18th-century “inventory” of antiquity, initiated by German historian and archeologist, Johann Joachim Winkelmann, was at the root of the West’s second love affair with the world of Greece and Rome. Prints with details and measurements of ancient temples and sculptures became a commonplace at the end of the 18th century. Their cheaper, less illustrious versions flooded the printing and book market in the first half of the 19th-century.

“Greeks are Us,” was the motto of all European Romantics, from Goethe to Byron, to Keats and Shelley, to Chateaubriand and Valéry, to Adam Mickiewicz and Juliusz Słowacki. Some of them could even compose their poems in Latin. In contrast to copper plates, which were used in the 17th- and 18th-centuries, the invention of steel-plates in the 19th century made it possible for thousands of ordinary readers of weekly magazines to familiarize themselves with the images of Greek and Roman architecture.

Albums with steel plates illustrations were printed in countless editions, and their prices were sufficiently low for anyone interested in antiquity to purchase them. The last act in the Greco-Roman tragedy of decline was the rise of the school of Neo-Classicism in painting and architecture. At the beginning of the 20th-century, the world of the ancient Greeks and Romans came to an end.

Paradoxically, this happened when Classical scholarship was at its peak, when complete critical editions of the ancient authors had been published. Individual editions were widely available, and Classical scholars could start working on their meticulous interpretations of each and every individual work that survived.

Proceeding roughly from the end of WWII, the number of hours devoted to studying Greek, Latin and the ancient authors would decline decade after decade. Today, learning Classics in most Western countries is not even required.

There are reasons why we find ourselves where we are and why the Classics have been demoted. The reading of Henry Nettleship’s “Classical Education in the Past and at Present” (1890) and John Stuart Mill’s “Inaugural Address to the University of Saint Andrew’s in Scotland” (1867), makes today’s reader aware that the mid-19th-century mind was already aware of the necessity of making room for science. The number of hours devoted to the study of different branches of science had to increase, but it was not the reason why the teaching of Greek and Latin started declining. The decline had roots in the rise of democratic mentality.

In 1816, in his speech “On the Liberty of the Ancients and the Moderns,” occasioned by Napoleon’s imperial adventures, rebuilding an empire, Benjamin Constant made an important observation: Napoleon was a ghost from the past, the man who tried to revive the ancient world, incompatible with the spirit of modern times.

Modern times, modern liberties, Constant argued, are incompatible with the bellicose and aristocratic spirit of ancient republics; modern life is based on commercial transactions, the desire to cultivate the private realm, independent of the collective, characteristic of the ancient Greek polis. The famous painting by Jacques-Louis David of Napoleon standing by a desk, under which there are two massive tomes of Plutarch’s Lives, is an allusion to where the spirit of the Empire comes from: The Greeks and the Romans.

In 1864, the French scholar Fustel de Coulanges published an influential book, La cité antique (The Ancient City). In it, he argued, that the state and religion in ancient Greece dominated every aspect of individual existence. Ancient democracy meant collective sovereignty; not individual independence protected by individual rights. Imitation of ancient republics would mean, as it did during Napoleon’s reign, giving up individual freedoms for the sake of ancient virtues.

The insights we find in Constant and de Coulanges do not make a case against Classical education, but they do point to the differences between the Greek and Roman world and Modern commercial democracies. The message was rather clear: modern man’s commercial spirit, need for privacy, and independence are incompatible with the ancient way of life. If so, it appeared more and more clear, classical education was unnecessary, or even useless.

Modern life and modern democracy called for a new, practical, form of education. Education meant no longer education to virtue – this being different in men and women – but education to democratic citizenship. The works by Rousseau (Emile and La nouvelle Heloise), or Laclos (On the Education of Women) looked out-of-date in the new world, just like reading Homer and Plutarch. Enough to contrast 20th-century books for children with their 19th-century counterparts, which were still heavily influenced by the Classics and told children stories about virtuous Greeks and Romans, to see the difference. Contrasting them with today’s children’s books, one gets the full picture. The characters are ordinary “kids,” living ordinary life, having ordinary problems. Hardly if ever they are inspired by a sense of greatness or excellence that the classics taught.

John Stuart Mill who since childhood was steeped in Classical education was reconciled to the advent of democracy, but saw it as fundamentally lacking in excellence. In his analysis of the differences between the ancient and modern mind, he finds the modern mind to be superior only in one respect.

Modern poetry, Mill writes, “is superior to the ancient, in the same manner, though in a less degree, as modern science: It enters deeper into nature. The feelings of the modern mind are more various, more complex and manifold, than those of the ancients ever were. The modern mind is, what ancient mind was not, brooding and self-conscious; and its meditative self-consciousness has discovered depths in the human soul which the Greeks and Romans did not dream of, and would not have understood.”

This is certainly true, and in this regard, the Moderns, who invented the novel – a form of writing unknown to the ancients – could indeed claim superiority. However, Mill also notices that in the manner of expression, the ancients were superior.

Their superiority stemmed from the fact that they addressed their writings to a small leisure class: “To us who write in a hurry for people who read in a hurry, the attempt to give an equal degree of finish would be loss of time. But to be familiar with perfect model is not the less important to us because the element in which we work precludes even the effort to equal them. The shew us at least what excellence is, and makes us desire it, and strive to get as near to it as is within our reach.”

Mill was not isolated in his observation, and most likely borrowed it from the French aristocrat, Alexis de Tocqueville, who, during his visit to America, observed a degenerative tendency of literary style in democratic societies. The claim of the superiority of the ancients in the realm of style, eloquence and historical analysis, to which Mill refers, invoking Thucydides, Quintilian, Cicero, Demosthenes, could, it would seem, serve as a strong argument for the mandatory teaching of the Classics in a democratic society: If the modern democratic mind cannot achieve the same level of excellence on its own, then, it follows logically, it should and ought to learn from the voices of their ancient predecessors.

This is what the American writer Henry David Thoreau postulated in the chapter on “Reading” in his Walden (1854). “For what are the classics but the noblest recorded thoughts of man? They are the only oracles which are not decayed, and there are such answers to the most modern inquiry in them as Delphi and Dodona never gave… Their authors are a natural and irresistible aristocracy in every society, and, more than kings or emperors, exert an influence on mankind… No wonder that Alexander [the Great] carried the Iliad with him on his expeditions in a precious casket. A written word is the choicest of relics.”

Thoreau’s use of the word “aristocracy” reveals the essential point in the discussion over the problem of classical education in a democracy. When, in 1987, Allan Bloom, The University of Chicago professor and a lover of Plato, published The Closing of the American Mind, he was viciously attacked. His book sold over a million copies. Bloom, the critics claimed, was an “elitist,” which was another way of saying, Bloom supports hierarchy!

But Bloom’s “elitism” was of a strange kind. Bloom encouraged students to read the Classics to understand what virtuous life is. He understood that the Greek and Roman Classics contain a world’s greatest treasure which cannot be found anywhere else. Ancient Greece, and Rome which perpetuated and spread the Greek intellectual heritage, was not one of many civilizations. It was the civilization par excellence, a yardstick against which we measure every other civilization.

The college curriculum given predominance to the Classics, in the language of his critics, was “discriminating” and based on “exclusion” of other cultures. And they were right! What is an elite, if not an aristocracy, and a class? But this strange class was not, like in the past, a class with hereditary privileges, but a class of readers – readers of the Classics. Bloom’s American “aristocracy” was not an aristocracy of color, ethnicity, hereditary privilege. It consisted of several thousand diverse students each year who read Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Plato, Aristotle, Plutarch, Cicero and others.

Instead of imposing “the elitist” curriculum on all, turning the American youth into the “elite,” the partisans of change – with Rev. Jessi Jackson, a loud proponent of educational destruction — did the opposite: They decided to close students’ access to the Greek playwrights, Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, Plutarch, and others by doing away with Western Civilization courses.

Why did they do it? They did in the name of multiculturalism, which is nothing other than intellectual egalitarianism. It claims all cultures are equal and none should be privileged. Therefore, the authors from other cultures are as good as the Greeks and Romans. They perceived the existence of Great Books programs, as we call the Classics in America, to be a mechanism of perpetuating educational—and thus social and political—inequality. Paradoxically, in doing destroying the traditional curriculum, they did what the Founding Fathers feared.

Thomas Jefferson – the man whose obsession with equality and hatred of hereditary aristocracy finds no equal in modern times – thought of natural aristocracy as a pillar of the democratic system of government, one without which democracy is bound to degenerate.

In his letter to John Adams (October 28, 1813), he wrote “For I agree with you that there is a natural aristocracy among men. The grounds of this are virtue and talents… The natural aristocracy I consider as the most precious gift of nature for the instruction, the trust, and government of society. And indeed it would have been inconsistent in creation to have formed man for the social state, and not to have provided virtue and wisdom enough to manage the concerns of the society. May we not even say that that form of government is the best which provides the most effectual for a pure selection of these natural aristoi into the office of government.”

A similar sentiment can be found in the English poet and a great literary critic Matthew Arnold: “We in England have had,” he writes in The Popular Education of France (1861; later published under the title, Democracy (1879): “in our great aristocratical and ecclesiastical institutions, a principle of cohesion and unity which the Americans had not; they gave the tone to the nation, and the nation took it from them… Our society is probably destined to become much more democratic: who will give tone to the nation then? That is the question. The greatest men of America, her Washingtons, Hamiltons, Madisons, well understanding that aristocratical institutions are not in all times and places possible; well perceiving that in their Republic there was no place for these; comprehending, therefore, that from these that security for national unity and greatness, an ideal was indispensable, would have been rejoiced to found a substitute for it in the dignity of and authority of the State.”

In contrast to Jefferson, who cherished the hope that we might find a mechanism to determine and select natural aristoi, Arnold understood that hierarchy is an indispensable component of every healthy society. Abolishing institutional hierarchy – written into the very fabric of society, either ecclesiastical or aristocratical – would mean to find an alternative mechanism that would make the wise govern. Reading Jefferson’s letter to Adams reveals that he had no clear idea how to solve the technical difficulty of finding democratic philosopher kings, without which – he, Hamilton, and Franklin thought — democracy could not last.

This asymmetry between democracy, understood as a universal right to vote, and the selection of the best (aristoi) from among the mass of enfranchised masses, has been resolved by neither Jefferson nor Mil. Retrospectively speaking, Arnold turned out to be more perceptive than Mill and Jefferson. He understood that aristocracy is not just a class of privileged people, but an idea, an idea inducing a sense of higher aspiration in ordinary people to ascend “higher” than where they actually are.

Such aspiration can be propelled only by the sense of greatness which the Classics teach us. When this sense of spiritual aspiration is no longer part of social and individual existence, a society is bound to lose the sense of cohesion and aspiration, and will slide into a moral abyss and lawlessness. And when it does, we will be forced to vest in the state power it should never have.

When undereducated, ignorant and vulgar citizenry lays claim to politics, one should not expect politicians to be anything other than demagogues. The annals of Greek political history are full of examples of demagogues, like the despicable Cleon. His power and influence were due, as we learn from Thucydides, to his understanding how weak depraved masses are and how to manipulate them. Anyone who happens to wonder why modern democracies display cultural malaise and galloping vulgarity in public and political realm should realize that there is a natural connection between virtue of citizens and the quality of public and political life.

In his quest for natural aristocracy in democracy, Thomas Jefferson reminds us of the Athenian philosopher Diogenes with a lantern in day-light. The latter was looking for an honest man; the former was looking for nobility in democracy. Their respective quests seem futile. After over two hundred years of modern democracy, one can say with certainty that we are unlikely to find nobility in democracy.

The only way to ennoble democracy is to teach young people the Classics. As Henry Nettleship wrote in his Classical Education in the Past and at Present (1890): “It must be remembered that the classics have still more than a merely literary function to perform. Greece was the mother not only of poetry and oratory, but—at least for the European world—of philosophy. And by philosophy I do not mean merely a succession of metaphysical and ethical systems, but the active love of knowledge, the search for truth. Will it be said that this spirit is not now as necessary as element in civilized human life as it ever was? In the long run it would almost appear as if it were mainly this which saves society from degeneracy and decay. The charitable instincts die out in an atmosphere of ignorance, for ignorance is the mother of terror and hatred…This is an inheritance as precious as Greek art and literary form; nay, if the continuous life of the nations be regarded, an inheritance even more precious.”

As a society, we have a choice between voluntary obedience to moral precepts we find in the Classical texts, or being forced to follow rules and regulations imposed on us by the State. Classics are not just about reading outdated works written by Dead White European Males. They also teach us virtuous behavior.

Zbigniew Janowski is the author of Cartesian Theodicy: Descartes’ Quest for Certitude, Index Augustino-Cartesian, Agamemnon’s Tomb: Polish Oresteia (with Catherine O’Neil), How To Read Descartes’ Meditations. He also is the editor of Leszek Kolakowski’s My Correct Views on Everything, The Two Eyes of Spinoza and Other Essays on Philosophers, John Stuart Mill: On Democracy, Freedom and Government & Other Selected Writings. He is currently working on a collection of articles: Homo Americanus: Rise of Democratic Totalitarianism in America.

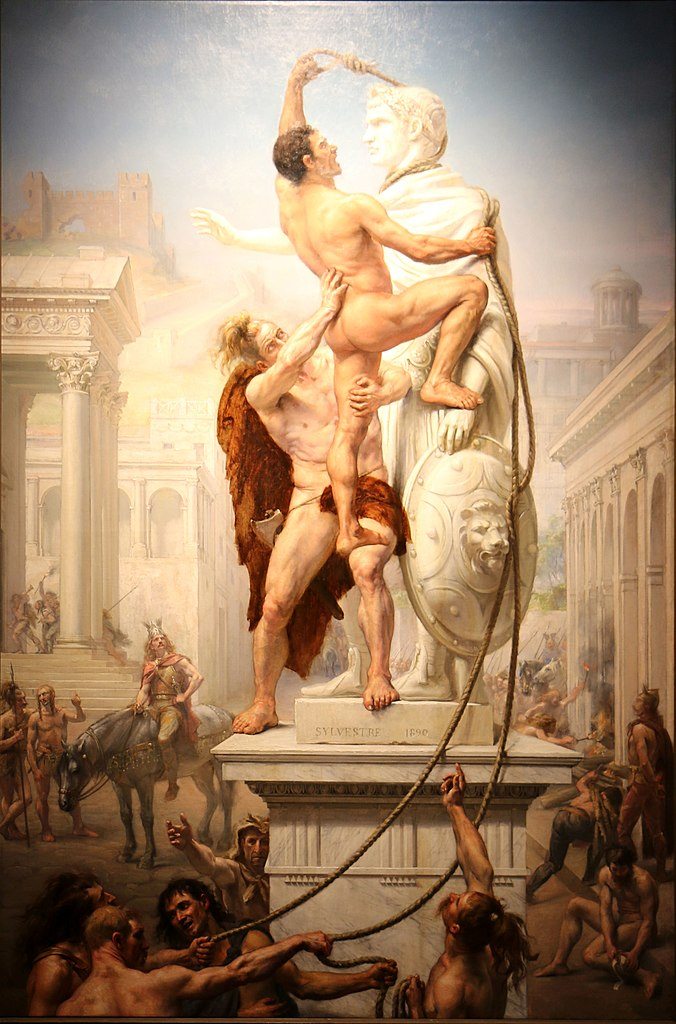

The image shows, “The Sack of Rome by the Vandals in 410,” by Joseph-Noël Sylvestre, painted in 1890.