This month we are so very pleased and honored to present this interview with the renowned philosopher, Nicholas Capaldi, who is the Legendre-Soule Distinguished professor at Loyola University, New Orleans, USA. He is interviewed by Dr. Zbigniew Janowski, who himself is a philosopher and author of several important books and is currently working on a collection of articles, entitled, Gods Will Have Blood: Rise of Totalitarianism in America.

Zbigniew Janowski (ZJ): My image of Nicholas Capaldi is that of an American intellectual and academic, rather than a philosophy professor. The reason is, correct me if I am wrong, that in your books you always try to tackle a big intellectual problem, just like in your book on analytic philosophy, which you inscribed in the Enlightenment Project. It is not just narrow philosophical problems that you see, but you see them in a broad historical context. The same goes for your other books and the one you have just finished, The Anglo-American Conception of the Rule of Law. Is my description of you correct?

Nicholas Capaldi (NC): Yes! Thank you. Philosophical issues do not exist in a vacuum but within a larger context. It is always important to ask “why” an issue is an issue and for whom. The academic world, wrongly modeled along scientific grounds, forces people to know or think they know more about less and less. The result is a series of fashionable discussions akin to a carousel on which the riders and tunes change but there is no progress or direction.

ZJ: Your other book is a biography of John Stuart Mill, the father of the Liberal Idea. What made you write it?

NC: As an undergraduate seeking to find my own voice, I was inspired both by Mill’s defense of individual autonomy and by the critique of censorship. A career in academe has only reinforced the need to seek for the truth and to be free to articulate it, even more so as the academic world becomes increasingly politicized and intolerant.

ZJ: As the author of two books on Mill, you are well qualified to assess Liberalism as a doctrine. Liberalism travelled a long way from where it started in 1820, as a criticism of the establishment of the aristocratic Anglican order to what it became in Mill, and to where it is now, essentially a form of Politically Correct orthodoxy. One could probably find a number of other intermediate stages in the 20th century (welfare state, extension of suffrage, etc.) How do you explain its plasticity, the ability to adapt itself to the changing circumstances? In ten years, it will be roughly 200 years since the emergence of the Liberal Idea in Oxford in the 1820s, as Cardinal John Henry Newman explained it in his Apologia.

NC: I think it is a mistake to talk about Liberalism. It would be better to focus on the importance of individual freedom and how it emerged/developed historically within the European psyche, but most especially in the English world. Once you try to understand this as an isolated concept (philosophical, political, economic, etc.) you have created a contextless abstraction – and abstractions can be interpreted to mean anything. The best discussion I know is Oakeshott’s distinction between civil and enterprise association, wherein the former is a society without a collective end, but exists to allow individual members to pursue their own individual ends with a minimum of conflict.

The existence of people (anti-individuals) who are incapable or unwilling to live in such a world enables them to take an abstract concept and make it mean the opposite of its original meaning. I might add that intellectuals who are limited to using only Greco-Roman models have bought into an intellectual frame of reference that limits their ability to understand individual freedom. Such intellectuals want to be free to impose their own model on others – freedom of speech for them means freedom to impose their private vision on others.

ZJ: What, in your opinion, were the classical characteristics of Mill’s Liberalism and which are the ones which today’s Liberals promote?

NC: Mill sought to respect individual freedom; today, many so-called Liberals seek to “promote” individual freedom by collectivist means. Assuming they know what they are talking about, they are blind to the inherent contradiction of ‘forcing people to be free’ (Rousseau). It all goes back to what Voegelin called “Gnosticism.”

ZJ: Let me give you one example, from his On Representative Government. Mill was a great proponent of universal suffrage. Yet, he understood that it was not a God given right, like the American inalienable rights, but contingent upon certain factors – education, for example. “Universal teaching must precede universal enfranchisement.” In other words, basic education, which he considered to be the knowledge of basic mathematics, reading, geography, national and world history is the foundation on which suffrage rests. We, today, on the other hand, believe that it is a right, that democracy can function anywhere, and that regardless of our personal and intellectual qualities, democracy can function. Democracy in Mill’s writings appears to be a very fragile and complex mechanism. How would he see the democratic world today?

NC: Mill wrote the essay, On Liberty, in part, to call attention to the difference between the negative role of democracy in the eighteenth century (favored by the U.S. founders) and the “tyranny of the majority,” against which Tocqueville argued so eloquently. Mill also called attention to the difference between what the majority might think and what those who claim to speak for the majority (power elite) claim on behalf of the majority.

ZJ: We seem to be obsessed with the idea of wide participation of the masses. No exclusions; in fact, every exclusion is called discrimination. Mill, sympathetic as he was to the idea of extending the right to vote, was very clear that, first, criminals’ right to vote should be suspended, that people who live off others should not have a right to vote, and those who are unemployed for an extensive period of time (he thought of 3-5 years), should not have a right to vote either. Today, Mill would be accused of discrimination.

NC: Today, democracy has become a mask for oppression. So-called “identity politics” brings together all the of the anti-individuals (mentioned earlier – see Oakeshott) to undermine the achievements and prestige of autonomous individuals. Instead of transferring resources from the rich to the poor, we transfer power from individuals to the state (de Jouvenel). Political discourse has become Orwellian.

ZJ: Let me go back to his educational requirements – literacy, national history, global history and geography. This is what he thought was necessary in 1861 when he published his work! The world of 1861 and the world of 2020 are not the same, and by that, I mean the world is so much more complicated and complex that even the best educated among us cannot claim to be experts in political matters.

Let me draw a parallel, I am not sure how useful it is, between criticism of Socialism by Hayek and democracy’s ability to sustain itself. According to Hayek, one major reason why Socialist economics is not viable is because no one can have complete knowledge that goes into pricing, and therefore, only free market can provide us with correct price of goods. Planned economy can’t work. The idea that the masses somehow have enough knowledge to run the social and political realms seems to me Utopian in nature, in the same way that Socialism was.

NC: You are absolutely correct. Keep in mind that Hayek’s argument against planning is a restatement of his mentor Mill’s position that no one can be infallible (remember the context of 19th-century debate on infallibility). The U.S. was founded as a Republic (constitutional protection of individual liberties) as opposed to a DEMOCRACY (majority-tyranny).

ZJ: In the beginning of his On Liberty, Mill states: “The struggle between Liberty and Authority is the most conspicuous feature of history with which we are earliest familiar, particularly in that of Greece, Rome, and England. But in old times this contest was between subjects, or some classes of subjects, and the government.”

This idea sounds very familiar to the readers of Marx and Engels, who at the opening of the Communist Manifesto formulated their vision of progressive history as well. In their view history is a class struggle, between oppressors and the oppressed. The oppressors are in Mill’s scheme the Party of Authority, and the oppressed are the Party of Liberty. Is it a coincidence that Mill – the Liberal – and Marx and Engels sound so alike? Or does the similarity stem from the popular understanding of History as Progressive, a popular conception in 19th-century.

NC: Great question. There were different conceptions of history in the 19th-century debate. For the mature Mill, history evolved but did not progress; as in the common law, we constantly seek to retrieve, explicate, and restate for new contexts the inherent norms of our inherited civilization. For Marx, Comte, etc. “history” was understood “scientifically” as a form of teleology or progress. The great attraction of the latter view is that it allows you to invent self-serving narratives.

ZJ: Do you think there are consequences of such an interpretation of history? In Marxism it was called “Historical Inevitability,” which in practice gave the communist apparatchiks a theoretical tool to eliminate the enemies: If History is progressive, if it unfolds itself in a certain direction, there is nothing wrong in eliminating the enemies of Progress. The idea had serious consequences in real life. Millions of people killed! The Stalinist trials, for example, are a good exemplification of it.

Let me quote a few sentences from Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon, a book about trials, in which Gletkin, the interrogator, explains what kind of historical thinking drives the communists and what justifies the elimination of the enemies: “My point is, one may not regard the world as a sort of metaphysical brother for emotions. This is the first commandment for us. Sympathy, conscience, and atonement are for us repellent debauchery… to sell oneself to one’s conscience is to abandon mankind. History is a priori amoral; it has no conscience.”

Thus, one can torture, kill. History provides justification. Are today’s Liberals heading in the same direction? Not necessarily by physically extermination, but by destroying everyone who disagrees with them? I am asking this question because their intolerance is growing; they attempt to shout down any critical voice; they become increasingly more violent; and the words, such as progress, progressive agenda, progressive policies, etc. are their only vocabulary.

NC: I fear that you are correct. All of this nonsense reflects the fact that the British and U.S. Revolutions were “conservative” in the sense I attributed to Mill above. The Russian and all subsequent Revolutions have been “radical,” that is, based on abstractions. Furthermore, the intellectual origin of all of this dangerous nonsense is what I have described as “the Enlightenment Project” – the belief that we could construct a social ‘science’ and thereby a social technology. You alluded to this in mentioning my other book. Like all bad ideas it originated in 18th-century France. If there is a social technology then dissent undermines utopia. Again, this appeal to infallibility is what Mill objected to in Comte.

ZJ: These dangerous tendencies in mass behavior are not new. They were noticed by philosophers, sociologists and psychologists. Let me begin with Mill who talks about tyranny of the majority in a democracy often in his On Liberty. How do you account for his favorable, even enthusiastic support for the rule of the majority, on the one hand, and his contempt for them (the collective mediocrity), as he refers to them?

NC: Mill saw political democracy as inevitable—curiously a product of industrialization. What he advocated was a cultural and political bulwark against its excesses.

ZJ: Was his contemporary, Nietzsche, a more perceptive critic of democracy and majority rule than Mill? Sometimes they sound the same, but Nietzsche took the masses for what they are – mediocrity, and saw what Mill refused to see – lack of aristocratic virtues. In fact, Mill hated aristocracy; wrote nasty things about it. Do you think it was a well-argued position, or was it a psychological suspicion of someone who did not belong to an aristocratic order, and who gave support with the power of his considerable intellect to the rule of mediocrity?

NC: lan Kahan has written a good book, Aristocratic Liberalism, in which he makes the case that Mill, Tocqueville, and Burckhardt were exemplars. I have argued that England (individual autonomy tradition) was different from the Continent (long history of collectivism). I see Nietzsche as responding to the more threatening Continental context.

Elsewhere, I (following many previous writers) have identified the extent to which intellectuals are attracted to holistic, collectivist, and Utopian thinking (e.g. Enlightenment Project, Hoffer’s men of words in his book True Believer). So, it is no surprise that the ‘Continental Disease’ has slowly infiltrated the Anglo-American world.

I also believe that the cultural dimension is more important than the purely intellectual one. In the U.S., many ordinary people understand and respond positively to Clint Eastwood’s Western films and to Frank Sinatra’s song “My Way.” This is behind Buckley remark that some of us would rather be governed by the first 300 people in the Boston telephone directory than the faculty of Harvard.

ZJ: Ever since the beginning of the 20th-century, that is, the rise of psychology and sociology, we know not only how, but why masses behave the way they do. Freud devoted an interesting book, The Group Psychology, to the topic. In a nutshell, man loses his individuality and identity in a crowd. Following Le Bon, Freud claims, man goes back to his primitive instinct and nature, and acts like a member of a herd, again, an expression that Nietzsche uses frequently to describe what he calls slave-morality. Only individuals, not crowds, not masses, have a moral compass. How does it square, in your view, with the idea of a democratic, mass society? Is such a society bound to be immoral?

NC: This is the very issue that Oakeshott addresses in his essay, “The Masses in Representative Government.” His conclusion was that “….[the anti-individual or mass man] remains an unmistakably derivative character…helpless, parasitic and able to survive only in opposition to individuality….The desire of the ‘masses’ to enjoy the products of individuality has modified their destructive urge.”

ZJ: Let me turn to something that has been on my mind, and which made me put out a new edition of Mill’s writings, where I think one can trace the trajectory of his development; namely, the idea of authority, which is so inimical to Mill. He made it, as the quotation from his On Liberty which I used before reveals, the centerpiece of his philosophy. Authority is the enemy of Liberty. Plato, in Book. VIII of his Republic, on the other hand, saw the dissolution of authority as the beginning of anarchy, which, in turn, is the result of expanding equality in a democracy.

Now, Mill, as you know, translated several of Plato’s dialogues and knew his philosophy well. Did he miss something? Did he expect democracy to last despite Plato’s warnings? Or did he think that everyone is rational? Or was he just too steeped in the English tradition of respect for law, order, conservatism in private life, etc.? Did he think that the social order is self-sustaining, that we will not cross a certain line? How would you explain his position?

NC: The intellectual and moral responsibility of the public intellectual, whether he/she be Plato, Mill, or us, is to (1) identify the social problem, (2) defend one alternative solution/policy against others, and (3) offer a rhetorical (artistic) expression, designed to persuade others to see the world as we do. Plato clearly did this in writing dialogues. You captured some of this in your collection of Mill’s more popular writings. You also capture this in some of your own cultural writing. It has been my great failing not to have done more of this in my own.

ZJ: Is the suspicion or hostility, in your view, as it is in Mill, characteristic of Liberalism? And if so, how far can the Liberals go, you think, without destroying social order?

NC: The greatest threat to tyranny is the capacity of a few people to stand up and say, “The Emperor has no clothes.” Keep it simple, clear, and authentic. It takes enormous courage to do this. In the end, the question is never how far tyrants will go, but how far we are willing to go to oppose them.

ZJ: Let me return to the idea of order. In Aristotle, we find a claim that the function of a good law giver is to make citizens good. In his defense, one of Socrates’ accusers makes the same point. When I taught those thinkers, it struck me that if Aristotle had a chance to read the American founding documents—pursuit of happiness, that is, leaving an individual to his own devices, without any moral compass—he would give the Founding Fathers an F. The idea that human behavior can be left unregulated would be preposterous to the ancients.

Now, given the American Founding Fathers’ brilliance, did they miss something? It is unlikely, which leads me to my question. The US was founded by the sectarian Protestants, with a very strict moral code. They, particularly Jefferson, could believe that the public realm can remain neutral because the citizens’ religiosity, or the Churches, will keep pumping, so to speak, the moral code. What are your thoughts on this?

NC: I think you are correct. The U.S. is, as Samuel Huntington said, an Anglo-Protestant culture. I would also make the case that since Mill and Nietzsche, it has become necessary to find an intellectual/cultural defense of the values of such a Protestant culture not tied to a specific theology as traditionally understood. I have tried to make such a case in a way that is compatible with some but not all traditional forms of the Judeo-Christian tradition.

Curiously, we live now in an increasingly secular culture where clergy who no longer believe in God are attracted both to mindless defenses of abstractions, like tolerance of intolerant religious sects and movements, and, at the same time, a therapeutic view of the welfare state as the new moral community. When I meet such people, I am not sure whether I should laugh or cry. Perhaps we need a new Reformation. This is part of what it means to retrieve our moral tradition in a new context. Retrieving a tradition can never be a simple matter of an uncritical return to the past. Instead, it is the re-identifying of something that is a permanent part of the human condition, even though it is always expressed in specific historical contexts.

ZJ: Now, 250 years later, with the decline of religiosity, low church attendance—and the same seems to be true of Judaism (as my Orthodox Rabbi friend tells me, reformed Judaism is likely to cease to exist in a few decades) – there is no moral or ethical powerhouse. It is almost as if Sartre and de Beauvoir’s dream came true. Everyone invents his own moral code, lives according to his own rules. Are we becoming a nihilistic society? Is this nihilism?

NC: I would make two points. First, there are lost souls, some of whom embrace the latest fashionable, and sometimes destructive, enterprise association. Second, nihilism is not to be confused with moral pluralism. We have always lived in a morally pluralistic world. The mistake we have always made is to try and find the one new true collectivist faith and impose it on others.

What we need, and what we have to some extent, is a plurality of substantive moral communities who need to agree on common procedural norms. I think many such communities exist. I think some of those communities presently lack the internal resources to agree to common procedural norms. In our book on The Anglo-American Conception of the Rule of Law, my wife Nadia and I have tried to show how this is possible and actual.

ZJ: Just like Mill, Jefferson was hostile to aristocracy, in his own, so to speak, American way. He saw it as an extension of monarchical order rather than a class, or much less so, because in one of his letters, he made a very strong case for aristocracy of spirit, education. He even designed a way how such a democratic aristocracy should be bred. In one letter he made a list of mad European monarchs, which, he thought, to be a very good case for abandoning monarchy as an institution.

Now, let me make this point – seceding from the British Crown, declaring independence from Britain, is one thing, establishing a new political order is another. So, after painful debates, the Americans chose the republic. Here is my question – one could believe, as Jefferson did, back then, that a monarch can become crazy and corrupt, but, one could argue, that one can replace a corrupt or mad monarch. However, when the masses become corrupt, what then? What can you do? And our present social and political situation seems to point to a number of problems which, on an individual scale, you could term unhealthy, or even insane.

NC: There are a number of issues here that need to be separated. First, I do not believe that the “masses” correctly captures the major issues. There are many people who cannot be classified as “intellectual,” but who are decent individuals and responsible citizens. You do not get to be decent and responsible by having a Liberal education. Second, the social pathologies I do see reflect the failure of major institutions (e.g. family, schools, religions). The failure of those institutions I would attribute to the false idea that we can have a social technology (i.e. the Enlightenment Project).

ZJ: You are an academic, having spent your life in academia. But you are more. You are associated with the Liberty Fund. When I think of the several conferences that I attended, I cannot resist the feeling that I have never, and I mean it, participated in more intense intellectual life than during the two days of their sessions. It is not only a well-organized setting, but it is a place where ideas matter. I am sure that you will agree with me. No university produces such an intense intellectual atmosphere as does the Liberty Fund. Do you agree?

NC: I would indeed agree. As long as the administration of Liberty Fund is true to donor intent, and is not captured by ideologues with a program, it remains the premier educational institution in America. Again, I would argue that the intellectual world in the last century has been a captive of the Enlightenment Project program of social technology. So-called higher education now disfigures the intellectual world, the worlds of the clergy, government administration, communication and journalism, law schools, teacher training, business, the arts, etc. At the risk of sounding self-promoting, higher education now controls the commanding heights of all that is wrong with our society.

ZJ: Given the absolutely dreadful state of education and universities in America, do you see a way out? The tenured academics will not give up their positions. Has academia been destroyed? Almost every week you can read an article of complaint from retiring academics stating how bad things are. Few people have the courage to stand up; and the majority of professors are afraid—afraid of students and administration. How did we come to be where we are?

NC: This is a long story. I started writing a book about it and became too depressed to finish it. It cannot be reformed internally, in part for reasons to which you have alluded. It can only be reformed from the outside. I do not see that happening in the short run. Our only hope is that it will collapse on itself, and the current financial crisis (student loan debt) may be how it happens. This is not an excuse for doing nothing – we keep up the rear-guard action. What we need to prepare is a positive alternative.

ZJ: What about the Liberty Fund method of education? Don’t you think that there is room for it to do the same kind of seminars with students? That Liberty Fund and other foundations could start real universities where education is what it used to be?

NC: I think the Liberty Fund model is a good one. I also think that education cannot be left to professionals alone. The articulation, defense, and critique of our fundamental norms should go on in every institution. The life of the mind also has intrinsic value. I end this interview as I plan to enter retirement with a program called “Community of Scholars.” Free from the constraints of teaching those who do not want to learn, freed from administrative B.S., free from the tyranny of journal editors and university presses; and with the help of the new technology and social media we can create a vast network of scholars who want to search for and articulate the truth, who want to share – for free – the wisdom of a lifetime of searching, and to do so in the spirit of Mill’s and Nietzsche’s ruthless self-examination. It requires both intellectual and moral virtue. It is our way, perhaps the only way, of keeping the Socratic faith.

ZJ: In 1977 Leszek Kolakowski published his opus magnum, Main Currents of Marxism. Its Rise, Growth and Dissolution. The first volume deals with the founders; the second with the golden age; the third with Marxism’s demise. Kolakowski’s work is, as I like to think about it, a death certificate of Marxist thought issued twelve years before the actual burial of Communism in Eastern Europe, and fourteen years before the end of the Soviet Union.

In his work, Kolakowski describes the vicissitudes of Marxism as a philosophy and practice. You wrote two books on David Hume, a massive book on the Enlightenment Project in analytical philosophy (or conversation!—as you called it), Liberty and Equality in Political Economy: From Locke versus Rousseau to the Present; and just a few months ago, you and your wife Nadia Nedzel, published The Anglo-American Conception of the Rule of Law.

The range of your interests is impressive, but you also wrote a fantastic biography of John Stuart Mill – a great read! Would you feel tempted to write a work on Liberalism à la Kolakowski’s Main Currents of Marxism? You could even title it, “Main Currents of Liberalism.” From our private conversations, I gather that you are thinking about it. Any thoughts on this and how would you structure it?

NC: I am most definitely interested in writing such a book. The general thesis is that what I have called the Enlightenment Project (18th-century French idea that there can be a social science modeled after physical science and that such a social science will give us a social technology) is the origin of Doctrinaire Liberalism, Marxism, and Socialism – these are all expressions of this bad idea (all bad ideas, by the way, come from France).

Doctrinaire Liberalism, I shall argue, is a French abstraction that (a) misunderstands Anglo-American culture, (b) and tries to introduce Anglo-American virtues into the Continent, but mistakes the abstraction for the reality. The mistake is then read-back into Anglo-American culture by British and American scholars and activists – thereby providing a fake history. All versions of the Enlightenment Project ultimately become totalitarian – hence, why what is happening in the U.S. (under the Democrats, not Trump) parallels what happened under Marxism.

ZJ: Marxism died not merely because the countries of real Socialism could not compete with the Western Liberal democracies, because the economy started to crumble, because of politics, etc., but because faith in Marxism died. Marxism, in its different stages of development, was not only a philosophy and political orientation, but a religion that required faith. One could say that its longevity depended on the existence of the believers. A host of intellectuals, writers, artists were Marxists; they gave support to the idea. When they lost faith in it – partly because of the form in which it manifested itself politically and socially – Marxism lost its magical power. Do you find any parallels between Marxism and Liberalism? Liberalism has also evolved, manifesting itself in different ways.

NC: I think you are correct that ideologies die when people lose faith in them. I do not think that this will happen soon in the U.S. In the U.S., the weakening has just begun; we need to make people aware that they are succumbing to an intellectual disease. We need to persist in weakening the faith.

ZJ: At the very end of volume one, Kolakowski characterized Marxism as man’s greatest 20th-century utopia, a flight to freedom. Today, the young generation is not familiar with such a hope and the Socialist idea, but being Politically Correct (with its call to social justice, the abolishing of “power structures,” etc.), which is a reformulation of Marxism. Do you think that the Liberal Idea is another utopia which replaced the old one, Marxism?

NC: Liberalism is just another version. What people confuse is our institutional structure with theory; we need to remind them that our structure is an historical product and not a theoretical product. I tried to initiate that in the book on The Anglo-American Conception of the Rule of Law.

ZJ: There are a number of books on Liberalism, beginning with Hobhouse’s classic, Liberalism (1911), which, in my opinion, comes very close to what we find in Mill’s writings; Harold Laski’s book The Rise of Eurpean Liberalism is another minor landmark in the development of the idea, and a number of minor works (O’Sullivan’s Liberalism, Schapiro’s Liberalism, Brinton’s The Shaping of the Modern Mind, part of which is devoted to liberalism, and so on). What is probably the most ambitious and serious book on the subject is De Ruggierro’s History of European Liberalism. It occurred to me that one could write a book on the development of Liberalism by tracing books called “Liberalism” or “History of Liberalism.” This is a phenomenon in itself, which makes one wonder why Liberals must redefine or readjust the notion of what Liberalism is every decade or so. Do you have an explanation?

NC: There is a disconnect between theory and practice, a disconnect that the discipline of philosophy has encouraged, namely, the belief that we can theorize the relation of theory to practice. Intellectuals, as Schumpeter noted, are the culprits here. Intellectuals so want to be the new clergy, they are unwilling to acknowledge the limits of discursive reason.

We cannot defeat them with more theory; we need to root out the notion that reason exists independent of all context (almost every major philosopher from Plato on has made this mistake). In the 20th-century, only Oakeshott and a few others have tried to reign in this rationalism.

ZJ: Do you think there is a need for a work on Liberalism, like Kolakowski’s Main Currents of Marxism, particularly now that Liberalism has assumed a freedom-threatening posture (I mean the PC movement, which is very destructive, socially, politically and culturally), just like Marxism before? Need the people be reminded how Socialism began and deteriorated? Liberalism is no longer an idea that promises liberation from the shackles of oppression but, like Marxism, has become an oppressive system, very much like what Tocqueville feared democracy would become.

NC: Several of us should write about it – not one book but a host of books. I do not think “democracy” is the problem. I think the problem is a collection of elites (academe, journalism, military, business, Hollywood, technicians in IT, etc.).

ZJ: Does Liberalism require and depend on faith as much as Marxism did? When this faith dies, does the Liberal Idea die with it?

NC: It is the same faith. We need to make clear what that faith is. Voegelin identified it as Gnosticism, a form of Pelagianism. It will never disappear; it will simply assume new guises. We have to be patient in dealing with its eternal return.

ZJ: Under Communism, where I spent the first 25 years of my life, we had a mild Marxist-Leninism indoctrination (it was not that mild in the 1950s or the 1960s); but no one believed this ideological rubbish. Opposing it meant serious consequences, losing a job, interrogations, prison, sometimes “an accident” (death). But people opposed it; there was an underground/ samizdat press. We would read Hayek, Milton Friedman, Roger Scruton, Kolakowski, and others in horrible underground editions. One book would be read by twenty individuals. People made the effort to clear their minds of the ideological pollution. But now they attend official university classes in feminism, gender studies, environmental justice, domination, patriarchy, colonialism, women in art, literature, and many others.

Here is my question: Why this weakness of man under Liberal Democracy, why such blindness? Is it because Liberal Democracies do not go after your body, but your soul, as Tocqueville observed? People prefer to lose their souls – integrity, conscience – than their jobs? This is not a recent phenomenon. Tocqueville saw it in 1835!

NC: We have to remember that the vast majority of Americans do not have college degrees; that the U.S. culture is not primarily an intellectual culture but a practice/pragmatic culture. The infected part of the population consists of two groups: (a) Intellectuals taking their cue from the Continental abstractions I previously identified, and (b) College students – most of whom are disinterested in ideas.

The public has been totally turned off by the media journalists (“fake news”), so they remain uninfected; and the public is largely oblivious to what goes on in higher education and still thinks it is about getting a better job. The problem is the intelligentsia (vast literature on why totalitarianism appeals to them) and the intellectual students who are indoctrinated. Most students are ignorant, disinterested, turned off, and remain quiet as a defensive maneuver.

It is OUR job to attack the intelligentsia (and remain unpopular with fellow faculty) to educate and re-educate those bright students with whom one comes into contact, and to reassure, by our opposition, the disinterested students that they do not have to take left-wing intellectuals and faculty seriously. The latter, ironically, may be the most effective thing we do.

ZJ: Thank you, Professor Capaldi, for this wonderful conservation!

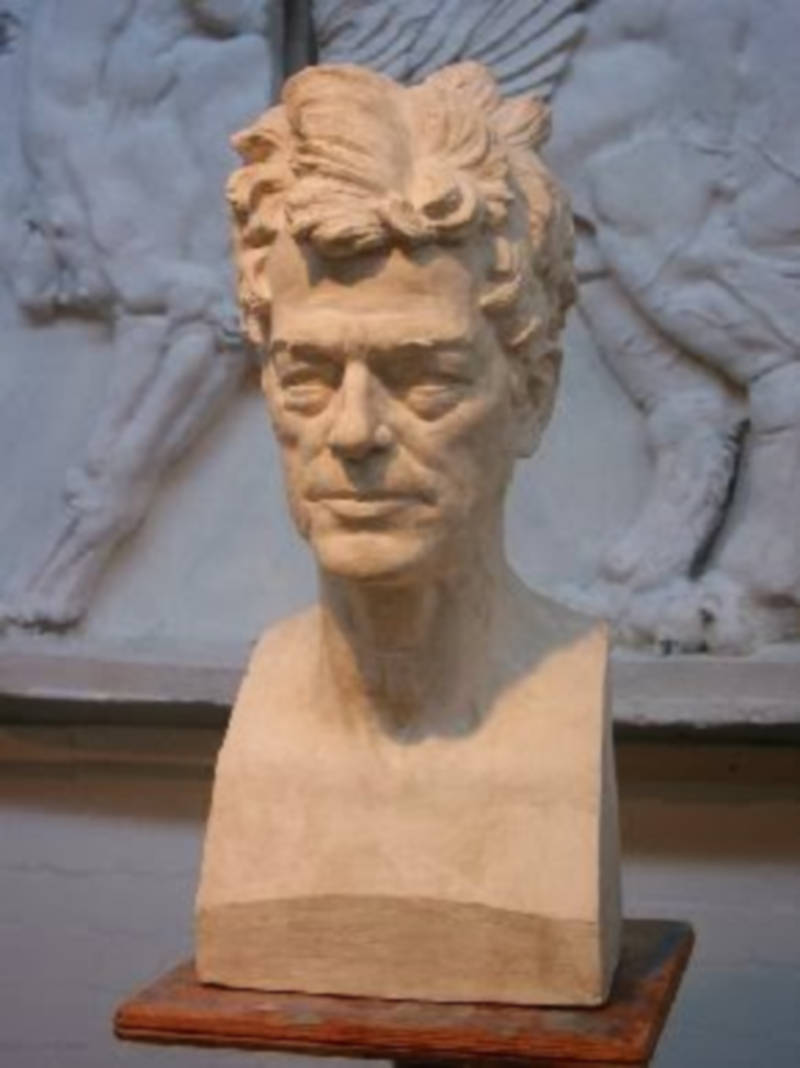

The image shows, “Danish soldiers return to Copenhagen, 1849,” by Otto Bache; painted in 1894.

A Polish version of this interview appeared in Arcana.