That which historians of language have long known and understood has been fully confirmed by a recent study of ancient Egyptian genomes.

Over the past many years, there has been a great deal of debate, almost always among those who want to further various political or racialist agendas, as to who the ancient Egyptians actually were.

Ownership of history is, of course, crucial in the realm of identity politics. The more history frays and is dissolved, or even becomes obliterated, the more readily identity may be constructed to suit political ends.

This is especially true among those who seek to carve out identity within the multicultural context of western societies, where the identity of the majority is made invisible, while the nationality (and therefore the history) of the various “ethnicities” is enlarged and “celebrated.” This, of course, leads to a distortion of history, making it into a romantic fetish.

Unfortunately ancient Egypt has suffered much distortion in this regard.

There is Joseph Smith’s and William Phelps “discovery” and “translation” of ancient hieroglyphic texts about Abraham and Joseph (Smith was often regarded as being proficient in reading and understanding the ancient language of the Egyptians). The story of Egypt plays an integral part in Mormonism.

These papyri (along with real mummies) had been profitably sold, in 1835, to Smith, by one Michael Chandler, a rather shrewd businessman, who in turn had bought them from the adventurer Antonio Lebolo, known for despoiling many an ancient tomb.

Then, there is the entire industry of Negritude and Black Zionism, which extends a black origin to all the civilizations of the ancient world, including Egypt (and even ancient Greece and Rome).

This has led to a common belief that since Egypt is in Africa, the ancient Egyptians were sub-Saharan Africans, i.e., they were blacks. The problem with this view is that it assumes that the passing millennia have had no effect whatsoever on the population of Egypt. Nothing could be further from the truth.

The fact is Africa did not become “black” until about 1400 AD, with the Bantu expansions and the eventual slaughter and reduction of other races, by them, that were living in Africa, such as the pygmies and the Khoisan.

As well, all of North Africa has always been “non-black,” and this includes Egypt.

However, modern-day mythologizers (the purveyors of “black racialism”) and the historians have always been at odds over this topic. The former seek to affirm the “blackness” of Africa, while the latter point to historical fact. Facts usually do not get in the way of politics.

Language is one such fact. The ancient Egyptian language (or Middle Egyptian), which came to be written down in hieroglyphics, hieratic and then demotic, is classified as an “Afroasiatic” language; but this is not as clear at it may at first seem.

As an Afroasiatic language, Middle Egyptian is a “cousin” to the Semitic family of languages, which in the ancient world included much variety (Akkadian, Babylonian, Ugaritic, Phoenician, Punic, Aramaic, Samaritan, Nabataean, Sabaean). In the present day, this variety has diminished to Arabic (and its various dialects), Hebrew, and Ethiopic (Ge’ez).

The ancient Egyptian language, therefore, was closely related to its Semitic cousins, most of which existed outside Africa proper; and thus it has long been suggested that that is where we must look for the point of origin of Afroasiatic (since all languages begin in a specific geographical location, from where they spread outwards).

The Russian linguist and historian, Igor M. Diakonoff, first outlined where the origin-point of Afroasiatic is found, by consideration of its earliest, or “proto” form. Words are given their proto-form by comparison with all of their cognates in other languages that belong to the same family group.

This reconstructed, earliest form of Afroasiatic is called, “Proto-Afrasian.”

Shared words, especially for flora and fauna, in the various related languages, point to a location on the map where such species of plants and animals are found.

Diakonoff’s study pointed to the Natufian archaeological complex as the location where Proto-Afrasian was first spoken.

The Russian archaeologist, Alexander Militarev, confirmed this location as the home of Proto-Afrasian, with his own study of the flora and the fauna of Palestine in its ancient context.

Thus, the ancient Egyptians were Natufians, who came into Egypt likely seven thousand to twelve thousand years ago.

This conclusion, provided by historical linguistics, has just been confirmed by the careful study of Egyptian mummy genomes, undertaken by Verena J. Schuenemann, and others.

Schuenemann and her colleagues discovered that the history told by ancient Egyptian DNA matches the history of linguistic fact:

- The ancient Egyptians have their origin in the Levant (modern-day Palestine, in Israel), and they migrated into the Nile Delta and the Sinai, bringing with them their goats and sheep.

- The ancient Egyptians were closely related to ancient and modern European populations, as well as ancient populations in what is now Turkey and Iran.

- The sub-Saharan admixture that is now evident in the modern Egyptian population is a recent occurrence, which took place during and after the Roman period.

This confirmation is significant because it suggests that historical linguistics indeed yields a highly accurate understanding of the movement of people.

Thus, who were the ancient Egyptians? They were indeed Natufians, and genetically related to people like the Phoenicians and the Canaanites of Palestine, like the Hatti (the pre-Indo-European people of Anatolia), and like the Elamites, (the pre-Aryan population of Iran).

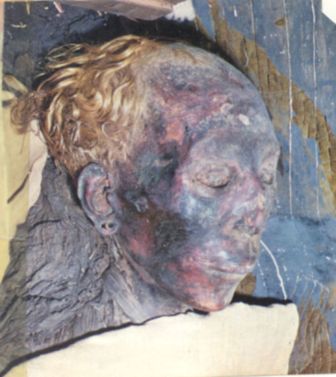

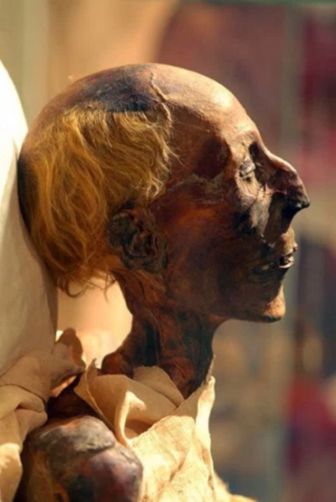

This also explains why there are red-haired and blonde mummies. Famously, Ramesses II had red hair, and Yuya and his wife Thuya are blonds, while brown hair was common.

We now need to work on placing the origins of the ancient Egyptians in their proper Middle Eastern historical, linguistic and genetic context.