An Introductory Digression

I first ran into Boris Poplavsky’s name in 1940 or 1941, and it was a case of mistaken identity. I was in Beverly Hills, California, at the home of a remarkable woman named Anna Semyonovna Meller, who in the days of my childhood was Madame Antoinette, the best known and most elegant couturiere in Harbin. My mother’s dressmaking establishment, Levitina-Karlinskaya, was not even a close second, but theirs was a friendly rivalry.

Anna Semyonovna’s adopted son Alex, six years my senior, was the idol and the despair of my Manchurian childhood: a champion ice skater, a concertizing pianist at the age of twelve, and a stoic who, during a hike in Chalantung, went on talking with a smile after a sharp rock had opened a bleeding gash on his knee. (I was half his age at the time and I remember screaming my head off at the mere sight.) Now, in California, he was a Surrealist painter, had been awarded a Guggenheim grant, and had spent a summer in New York, where he had met Pavel Tchelitchew (Chelishchev) and the son of Max Ernst and a number of other persons of equally supernatural stature.

Staying as a boarder at Anna Semyonovna’s was Alex’s friend Eddie, a young man of similar origins and background (his parents owned a dress shop on the Bubbling Well Road in Shanghai, and my mother had worked for them in her early youth), a former Berkeley architecture major who was now studying costume design at an art school somewhere near Westlake Park. Eddie’s sketches usually took first prize at school competitions, with the second prize going to his principal rival and fellow student, a melancholy-looking German refugee boy named Rudi Gernreich.

Waves of pure happiness would wash over me every time I waited for the Wilshire bus to take me for a day or a weekend to the Meller home in Beverly Hills, away from everything that made my life in Los Angeles glum and barely endurable: the incomprehensible courses in civics and physics (even their names seemed interchangeable) at Belmont High; the hopelessly boring afternoon job at the grocery store; and the pointless weekly exchange of mutual insults between Jack Benny and Rochester on the living room radio. (“It is all probably very funny and subtle, if we could only truly understand it,” my father would assure me after denying me permission to turn the dial to some concert music. But I did understand it all and it was not funny.)

At the Mellers’, things were altogether different. To begin with, it was perfectly all right to speak Russian and to have been born in China without having everyone exclaim, as they did at school, “How did you ever manage that?” or “Were your parents missionaries?” Instead of Jack Benny on the radio, there were real live stars to be encountered in Beverly Hills. Once I had to jump back when a long black car swung into a driveway with George Raft at the wheel and Rita Hayworth next to him.

Another time, Eddie and I were walking past the John Frederics millinery shop on Beverly Drive and were stopped dead in our tracks by the sight of the most unbelievably beautiful woman either of us had ever seen. She was selecting a hat inside. We stood there staring, exchanging whispered conjectures as to who this magical creature might be; then a saleslady came out, not to ask us to move, but to announce, “Miss del Rio would like to know which of the two models you gentlemen consider more becoming.” None of the Dolores del Rio films I saw later even began to do justice to the unforgettable radiance of her beauty.

Many years later, I felt a shudder of recognition as I watched that same scene reenacted (transposed into a comical key) in Billy Wilder’s film Witness for the Prosecution. Could Eddie have recounted it to someone during his brief career at the film studios? He was designing costumes for Gene Tierney and Maria Montez at Universal—or was it United Artists?—when he was run over and killed by a drunken driver. It happened as he was crossing Beverly Drive one evening in 1945, about half a block from where he and I had once stood admiring Dolores del Rio. Eddie also had connections in the world of burlesque. Rose La Rose wanted a new kind of stage costume and he came up with one that featured a quivering pink lobster over the G-string. One night he sneaked me backstage at the burlesque house on Main Street (I was too young to purchase a ticket), and I watched from the wings a performance of a tassel-twirler named Ermaine Parker. Afterward we went out for coffee with her and her tall, handsome husband, the straight man for the foul-mouthed, baggy-pants comedian in the show. The talk was mostly about the couple’s infant son, who had developed a liking for classical music before he learned to speak.

There were art exhibits of new painters, to which Alex or Eddie would take me: Salvador Dalí at the Ambassador Hotel, Eugene Berman and Christian Bérard at little galleries on Sunset Strip. But above all, books and poems were a part of daily life at the Mellers’. It was there that I was introduced to, or urged to read, Look Homeward, Angel; To the Lighthouse (which I couldn’t get through on the first try); Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog (the book that provided the model for the title came later); a volume of short stories by Noel Coward (which I still think quite good); and collections of poems by Wallace Stevens, Dylan Thomas, and (whatever happened to him?) George Barker.

While everyone at home and at school kept urging me to forget about those useless Russian books I was forever dragging about, Alex and Eddie, older and wiser, never considered giving up their cultural heritage. Alex had his cult of the “three fellow-Alexanders”—Pushkin, Blok, and Scriabin; he had given up playing the piano when he decided that, compared to the later period of Scriabin, all music was primitive and dull. The three of us used to get high reciting Blok to each other, mostly from The Mask of Snow and The Nightingale Garden cycles. But here I could contribute as well as receive.

One day, after leafing through A Synthetic History of the Arts, by a Soviet scholar named Ioffe, at the Los Angeles public library, I learned of the existence of Boris Pasternak and Velimir Khlebnikov. There was no Khlebnikov at the library, but I immediately copied out his poem about the grasshopper, which Ioffe had cited to illustrate some principle of modern painting or other. They did have My Sister Life and Themes and Variations. I took these over to the Mellers’ the next weekend, and while the older generation (Alex’s parents and his aunt Madame Olga) pronounced Pasternak incomprehensible, Alex and Eddie both agreed that here was a major discovery. I also introduced them to my favorite modern Russian novelist, a man I knew only as V. Sirin, with whose work I had become involved several years earlier. When I brought over my copy of Invitation to a Beheading, Eddie tried reading it out loud, but his long sojourns in Shanghai and Berkeley had done something to his Russian stress. (This was not noticeable when he spoke, only when he read aloud.) I took the book away from him and began to read slowly, getting all the stresses right, but after three pages I had to stop: Eddie was on the floor, his legs kicking in the air, a beatific smile on his face. “Stop it, I can’t stand it, it’s too beautiful,” he was moaning.

Alex’s reaction was a little more reserved. He kept the book for several days and when he returned it, he remarked, “If I were a writer, this is how I would want to write.” And a little later: “I had the damnedest feeling I wrote some of it myself.”

Sirin then joined Pushkin, Blok, Pasternak, Thomas Wolfe, and Dylan Thomas in our literary pantheon. It was on one such enchanted Sunday afternoon, leafing through the New York Russian newspaper Novoe russkoe slovo [published until 2010], to which Anna Semyonovna subscribed, that I came upon Poplavsky’s name—and this is where the mistaken identity part comes in. A memoirist (Yury Terapiano? Vladimir Varshavsky?) was reminiscing about the Russian Montparnasse of the 1920s. He could vividly remember the poet Boris Poplavsky drunkenly declaiming:

And the nightingale in the Sanskrit tongue

Shouts “More wine! More wine!” over the yellow rose.

The name was unfamiliar, but there was something about those two lines that made me resolve to look up their author. As a matter of plain fact, however, the lines were not by Poplavsky. I could never find them in any of his books, and after years of fruitless searching I finally, through sheer accident, discovered the awkward truth. The lines are a quotation from the Rubaiyat translated into Russian by Ivan Tkhorzhevsky. In connection with that translation Vladislav Khodasevich, when asked one morning why he looked so poorly, quipped: “I had a terrible nightmare. I dreamed that I was a Persian poet and that Tkhorzhevsky was translating me.” [The passage corresponds to stanza 6 of Edward Fitzgerald’s version, where the nightingale speaks in Pahlavi and the rose is sallow. The notes to my (New York, 1888) edition explain that the rose was yellow in the first edition of Fitzgerald’s translation and identify Pahlavi as the “old, heroic Sanskrit of Persia.” This seems to suggest that Tkhorzhevsky was translating Fitzgerald into Russian, rather than the original Omar.]

But never mind. These two lines of Tkhorzhevsky’s pseudo-Omar did direct me to Poplavsky.

The Discovery

The strange Aztec-Mayan pyramid that houses the main public library in downtown Los Angeles will always remain for me one of the endearing spots in Southern California. Its dark tile walls that kept the air comfortably cool on the muggiest days; the long, Alhambra-like vistas that opened from one room to another; the purling fountains in the inner yards (if I’m making it sound garish and eclectic, it no doubt was) I still find unforgettable. There was a Russian lady in the Foreign Books Room, whose name I never learned, who made it a point to purchase everything worthwhile in contemporary Soviet and Russian émigré literature. The library’s collection of volumes on Russian painters and painting and on the Soviet theater of the 1920s was nothing short of opulent.

Yes, of course they had Poplavsky at that library. There were two slim volumes: a selection from his journals and a volume of verse called Flags. I got Flags, opened it in the middle, and immediately felt as though I were falling through a hole in the ice. Nikolai Tatishchev described his first impression of reading Flags thus: “A pure and piercing sound. Hardly anything can be made out. Now and then something breaks through and stings you. ‘O Morella, come back, it will all be different one day.’ Alarm, apprehension. The barometer needle quiveringly indicates a storm. A degree of agitation that can be expressed only in deliberately approximate terms.” [N. Tatishchev, “O Poplavskom” [On Poplavsky], Krug [The circle], vol. 3 (Paris, 1938)].

This was how a mature person, a close friend of the poet and the publisher of his posthumous books, reacted to Flags. My own impression (and it remains one of the most vivid of my entire life) was somewhat different. I was struck first of all by the bright colors, the swirling images, the authenticity of the dreamlike states the poems conveyed:

In the emerald waters of the night

Sleep lovely faces of virgins

And in the shadow of blue pillars

A stone Apollo slumbers.

Orchards blossom forth in the fire,

White castles rise like smoke

And beyond the dark blue grove

Vividly dark sand is ablaze.

Flowers in the garden hum,

Statues of souls come to life

And like butterflies from the fire

Words reach me:

Believe me, angel, the moon is high,

Musical clouds

Surround her, fires

Are sonorous there and days are radiant.

My English cannot reproduce the pulsating music that emanates from these lines in Russian, nor does it convey the artful and often startling rhymes. There are pages and pages in this little book that project this blend of color and music, but there are also other things:

We shelter our caressing leisure

And unquestioningly hide from hope.

Naked trees sing in the forest

And the city is like a huge hunting horn.

How sweet it is to jest before the end

This is understood by the first and the last—

Why, a man vanishes, leaving fewer traces

Than a tragedian with a divine countenance.

There was an attitude in those poems, a vision, a sensibility quite new to me, but one that I instantly recognized and accepted:

But now the main entrance thundered and the bell started barking—

Springtime was ascending the stairs in silence.

And suddenly each one remembered that he was all alone

And screamed “I’m all alone!” choking with bile.

And in the singing of night, in the roar of morning,

In the indistinct seething of evening in the park

Dead years would arise from their deathbeds

And carry the beds like postage stamps.

I did not know enough about poetry at the time to recognize Poplavsky’s sources, to discern his French influences: Baudelaire (who had a greater impact on him than anyone except Blok), Nerval, Rimbaud, Laforgue, Apollinaire, Breton. I did not know then, as I know now, that Boris Poplavsky was in a sense a very fine French poet who belongs to Russian literature mainly because he wrote in Russian. But much of his sensibility was also a verbal equivalent of the visual imagery I knew and loved in the work of the exiled Russian neo-Romantic painters Pavel Tchelitchew and Eugene Berman. [“But Poplavsky’s surrealistic world is created illegitimately, using means borrowed from another art, namely painting (some of the critics have pointed out that Poplavsky is actually a visual rather than a musical poet; his poetry has been compared to Chagall’s painting…” Gleb Struve, Russkaia literatura v izgnanii [Russian literature in exile] (New York, 1956), 339. The observation is absolutely correct, but why is cross-fertilization between the arts illegitimate? Russian poetry of the twentieth century in particular has a deep-going and highly legitimate symbiotic involvement with both painting (Voloshin, Mayakovsky, Khlebnikov) and music (Bely, Blok, Kuzmin, Pasternak)].

An uncritical acceptance? I knew at once that much of what Poplavsky was doing was highly artificial. But I knew even then that artifice was a natural component of some of the finest art and had no objections. Despite its artificiality (and partly because of it), the book hit me with a wave of lyrical power I would not have believed possible, a wave that swept me off my feet and held me prisoner for many weeks. This was not like getting intoxicated on Blok’s verbal magic, nor was it like the intense intellectual pleasure afforded by Pasternak’s formal perfection and his freshness of perception.

Poplavsky came to me more like a fever or a demonic possession. I went around reciting Poplavsky’s lines by heart. I tried composing melodies to them. I discovered that stanzas 3 and 4 of his poem “To Arthur Rimbaud” could be conveniently sung to the tune of the clarinet solo from Tchaikovsky’s Francesca da Rimini, and I did sing them, obsessively. The next thing I knew, my mother, normally infuriatingly indifferent to poetry, was muttering Poplavsky to Chaikovsky’s music in an undertone while fixing dinner.

It was a heavy burden to keep to oneself at sixteen. I was fortunate indeed to have two older friends with whom I could share it. Alex and Eddie were almost as enthusiastic about Poplavsky as I. The three of us leafed through the fragments of his journals. We did not find his religious quest congenial, but the seriousness and depth of his spiritual experience got through to us, and his ways of formulating it we also found impressive. Seeing that Russian poetry could be this closely allied with Surrealism in painting, Alex was moved to write a few Russian poems, which were meant as literary parallels to his paintings. He submitted them to Novoe russkoe slovo and one of them was printed, not in that newspaper’s Sunday poetry section as he had hoped, but as an illustration to an editorial which discussed the poor quality of Russian émigré poetry and asserted that Surrealism as a whole was an unimportant trend, by now entirely passé and forgotten. Then Alex was drafted into the army. He wrote me asking for the library copy of Flags. I sent it to him, he returned it, then he wanted it again, and it was lost in the mail. I ruefully paid the charges for the lost book ($2.50, I think). A few months later it turned up at Alex’s training camp. When I tried to return it, I was told that there was no need, because the library had replaced it. I now had my own copy of a book by Poplavsky… But just who, exactly, was Boris Poplavsky?

Some Biographical Materials

Exhibit A: His Father

[The vice president of the Moscow Association of Manufacturers] was Yulian Ignatievich Poplavsky, an extremely original and colorful personality even for the Moscow of those days. Poplavsky was a musician. He graduated (with very high grades) from the Moscow Conservatory where he majored in piano and was one of the favorite pupils of Pyotr Chaikovsky, with whom he was on intimate terms, as can be seen from his memoirs. I do not remember what it was that moved him to give up his musical career and take up industrial relations….

Poplavsky was a talented person; one seldom encounters such facility with word and pen. He could discuss any topic and could treat the most serious subject in a frivolous vein. His speech mannerisms, which corresponded to his manner of dress, irritated many and Poplavsky was widely disliked. It was said that he was “barred from the stock exchange.” This seems to be factually correct: invitations were not extended to him and this would cause clashes between the Manufacturers’ Association and the Stock Exchange Committee. He was also active in St. Petersburg where he was the representative of his organization, together with Jules Goujon [the president of the Manufacturers’ Association] at the Convention Council. When a petition had to be drafted or a summary of a discussion prepared, he was irreplaceable and was able to draft them with the utmost ease and elegance.

Gradually, people became accustomed to his manners, and he began receiving invitations to Stock Exchange Committee sessions, especially when labor problems were involved, inasmuch as the antiquated organization of the Stock Exchange Committee was falling behind the times in collecting current statistical data and the documentation pertaining to labor problems. Poplavsky’s office on Miasnitskaia Street was excellently organized and the Association (it was in existence for only twelve years) was able to accumulate much valuable material.

[A portrait of Boris Poplavsky’s father, from Paul A. Bouryschkine, Moskva kupecheskaia – The Merchants’ Moscow (New York, 1954), 256–57. This little-known volume is an astoundingly thorough and convincing record of the contribution made by the traditionally maligned and despised Russian merchant class to the development of Russian culture, literature, and the arts during the century preceding the Revolution.]

Exhibit B: His Sister

I can still see one [of these poetesses]—tall, feverish, everything about her dancing: the tip of her shoe, her fingers, her rings, the tails of her sables, her pearls, her teeth, the cocaine in the pupils of her eyes. She was hideous and enchanting with that tenth-rate enchantment which cannot but attract, to which people are ashamed to be attracted, to which I am openly and shamelessly attracted.…

I can say in general that I was met with kindness in this alien world of female practitioners of drug-addicted poetry. Women are in general kinder. Men do not forgive felt boots or having starving children. But this very same P——skaya, I am convinced, would have removed the sables from her shoulders had I told her that I had a starving child at home.…

I did not get to hear the feverish, fur-clad beauty recite her poetry, but I doubt that cocaine could have disposed her to write of love.…

[Three glimpses of Boris Poplavsky’s sister Natasha, gleaned from Marina Tsvetaeva’s memoir A Hero of Labor (1925). Tsvetaeva and Natasha Poplavskaya both appeared at a reading of women poets in the cold and starving Moscow of 1920].

Exhibit C: His Biography

Boris Poplavsky was born in Moscow on 24 May 1903. His father was a free artist—a musician, a journalist, and a well-known social figure; his mother, née Kokhmanskaya, came from an old, cultivated, aristocratic family, had a Western European education, and was a violinist with conservatory experience. As a child, Boris Poplavsky was first looked after by his nanny, Iraida, and then by a German nurse and a French governess. Later, as an adolescent, he had Swiss and English tutors, and when he reached school age, he was taught by Russian university students, hired to give him lessons. He also studied music, but showed no enthusiasm; lessons in drawing, however, were always his favorites.

In 1906, his mother had to take the children abroad because of the severe illness of her daughter. They lived alternately in Switzerland and Italy, while his father remained in Moscow. While abroad, Boris forgot his native tongue to such an extent that, when he returned to Moscow, his family had to enroll him and his brother at the French lycée of Saint Philippe Néri, where he remained until the Revolution. Boris took to reading early … and it was hard to tear him away from a book. When his elder sister Natasha, a dazzlingly educated and talented girl, published a collection of verse in Moscow, where she was considered an avant-garde poetess, Boris, either through competitiveness or imitation, also began to practice writing verses in his school notebooks, accompanying them with fanciful illustrations.

When the Revolution broke out in February 1917, Boris was fourteen years old. In 1918 his father was forced to travel to the south of Russia, and he took his son along. Thus, while still quite young, Boris had to part from his family and experience all the horrors of the civil war. In the winter of 1919, when he lived in Yalta, he gave his first reading as a poet at the Chekhov Literary Circle. And in March of the same year he and his father emigrated to Constantinople. This period of his life can be summed up in two words: he meditated and prayed. All the money his father gave him, his own belongings, even his food, Boris gave to the poor; at times several homeless people would spend the night in his room: students, officers, monks, sailors, and others, all of whom were literally refugees.

In Constantinople, Boris attended a makeshift equivalent of high school, did a great deal of sketching, read a lot, occasionally took incidental jobs, and spent much time with the cub scouts at the Russian Hearth, which was organized by the YMCA. At the same time, Boris saw life through a veil of profound mysticism, as if sensing the breath of Byzantium which gave birth to the Orthodox faith, to which he yielded himself unconditionally. In June 1921, his father was invited to Paris to attend a conference on Russian trade and industry.

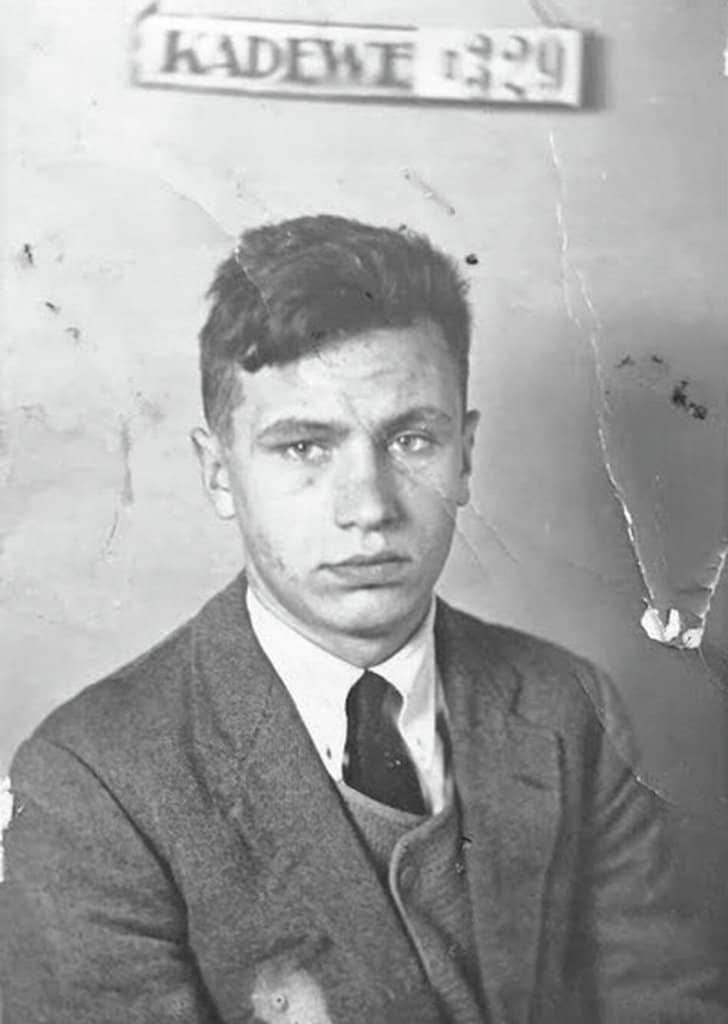

For ten years Boris lived in the Latin Quarter, during the last four on the rue Barrault near the place d’Italie. There he died in the little annex at number 76-bis, located on the roof of the immense Citroën garage. The exciting and intriguing city of Paris absorbed Boris so much that he left it only once, in 1922, to spend a few months in Berlin. There he moved in the avant-garde literary circles, often appeared at literary gatherings and artistic soirées, and made a number of literary acquaintances.

The Poplavsky family gradually all assembled in Paris and Boris’s life seemed to enter upon a normal course. He regularly attended the Art Academy at La Grande Chaumière and was later enrolled at the Sorbonne, majoring in history and philology. He immersed himself in philosophy and theology and spent long hours in the rare manuscript room of the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. He was a passionate book collector; he had two thousand volumes at his death. He regularly visited museums, where he would stay for days on end. He studied assiduously, practiced sports, and wrote. As in earlier days, he was interested in poetry, literature, economics, philosophy, sociology, history, aviation, music, and everything else. He was always in a hurry to live and work, and he sometimes dreamed of becoming a professor of philosophy in Russia … not merely when collective farmers got to wear top hats and drive around in Fords, as he put it, but when the persecution of faith would end and a free life of the spirit would begin.

His novel Homeward from Heaven, which is partly autobiographical, gives an idea of how Boris lived and worked in Paris. He frequently appeared at literary gatherings, debates, and conferences as the principal speaker or as a discussant; he was well known in literary and artistic circles. His close friends valued him as a religious mystic, a God seeker, and a perceptive philosopher and thinker. The last years of his life were profoundly enigmatic. Many found in him not only a friend, but a source of support for attaining an ideological turning point in their lives. He was destitute at the time, but he would still share his last penny with the poor.

A tragically absurd incident brought his life to an end. On 8 October 1935, Boris met a half-mad drug addict, who under the pressure of his own adversity decided to commit suicide and wrote a suicide note, addressed to the woman he loved. He persuaded Boris, “on a dare,” to try out a “powder of illusions,” but instead, excited by the maniacal idea of taking a fellow traveler along on his journey to the beyond, gave him a fatal dose of poison, taking one himself at the same time.

Boris left behind two parts of a trilogy in the form of two large novels, Apollon Bezobrazov and Homeward from Heaven, and sketches for the third part, The Apocalypse of Therese. Then there are three volumes of verse ready for publication, a philosophical treatise on logic and metaphysics, the essay “Solitude,” a multi-volume diary, notations, drawings, letters, his favorite books which contain many jottings on the margins, and a great deal of other material, which so far has not been sorted out.

Paris, October 1935

[Yulian Poplavsky’s biography of his son, slightly abridged. [Iu. I. Poplavskii, “Boris Poplavskii,” Nov’ (Tallinn), no. 8 (1936): 144–47.]

Exhibit D: A Friend

I began writing verse quite early, and in 1920 Boris Poplavsky and I organized a Poets’ Guild in Constantinople.

Vladimir Dukelsky, alias Vernon Duke. [Autobiographical note in the anthology Sodruzhestvo (Washington, 1966), 521. Although both wrote poetry at the time, it was the future composer of Cabin in the Sky and Le bal de blanchisseuses who considered himself a poet then, while Poplavsky saw himself as a future painter.]

Exhibit E: Self-Portraits

- “Poverty is a sin, retribution, impotence, while luxury is like a kingdom in which everything reflects, extends, incarnates the slightest flutter of God’s eyelashes. And nevertheless, stoically, heroically, Oleg managed to bring his life to a realization, extricated it out of its wraps, despite poverty, inertia, and the obscurity of his underground destiny. Having received no education, he wrenched one for himself from the stained, poorly illuminated library books, read while his behind grew numb on the uncomfortable benches. Anemic and emaciated, by abstinence and daily wrestling with heavy iron weights, he forced life to yield him cupola-like shoulder muscles and an iron handgrip. Not handsome, unsure of himself, he used his hellish solitude, know-it-allism, valor, asceticism to master that fierce eye mechanism which was able to subjugate, at times to his own amazement, female heads radiant with youth. For Oleg, like all ascetics, was extraordinarily attractive, and his ugliness, rudeness, and self-assurance only enhanced his charm. Life refused him everything and he created everything for himself, reigning and enjoying himself now amidst the invisible labors of his fifteen-year effort. Thus, in a conversation he would calmly and slyly radiate the universality of his knowledge, which astounded his listeners as much as did the ease with which he could, while sitting on a sofa, lift and toss about a thirty-kilogram weight or a chair, held horizontally by its back in his hand, as he laughed at the gloomy, lifeless, unascetic, sentimental, disbelieving Christianity of the Paris émigré poets.”

- “You thought, Oleg, that you could at last do without God, rest from His insatiable demands; and see, now He is doing without you.… Look, nature is about to enter upon her sad, brief summer triumph and you were asleep, your heavy head full of the hot waters of sleep, and you dreamed of earthly, full-blooded, bearded life. Once again you were insolent to God, Oleg, and tried living without Him, and your face hit the ground, heavily, stupidly, clownishly. You finally awoke from the pain, took a look around, and see, the trees are already in bloom and have hung out their vivid, abundant new leaves. It is summer in the city and again you are face to face with God, whether you want to be or not, like a child that conceived the wish to hide from the Eiffel Tower behind a flowering shrub in the Trocadero garden and after walking around it was instantly overtaken by the iron dancer-monster that takes up the entire sky. You try not to notice it, but it hurts you to look at the white sky and a heavy, sweaty stuffiness is pressing on your heart. You are again in the open sea, in the open desert, under an open sky covered up by white clouds, in the intolerable, ceaseless, manifest presence of God and sin. And there is no strength not to believe, to doubt, to despair happily in a cloud of tobacco smoke, to calm yourself at a daytime movie. The entire horizon is blindingly occupied by God; in every sweaty creature He is right there again. Eyesight grows dim and there is no shade anywhere, for there is no home of my own, but only history, eternity, apocalypse. There is no soul, no personality, no I, nothing is mine; from heaven to earth there is only the fiery waterfall of universal existence, inception, disappearance.”

[Two of Boris Poplavsky’s self-portraits as Oleg in his novel Homeward from Heaven. Fragments from Homeward from Heaven, in Krug, vol. 3].

Exhibit F: The Critical Response

[R]ecently Will of Russia (Volia Rossii) discovered the amazingly gifted B. Poplavsky. Of all his delightful poems it printed, not a single one could have possibly appeared in Contemporary Annals (Sovremennye zapiski)—they are far too good and uniquely original for it. [Georgy Ivanov in Latest News (Poslednie novosti), Paris, 31 May 1928]

Among the Parisians, Boris Poplavsky is particularly outstanding. Some of his poems (especially the one with the epigraph from Rimbaud that appeared in volume 2 of Poetry and the “Manuscript Found in a Bottle” in Will of Russia, number 7) force one to stop and listen in astonishment to the voice of a genuine and entirely new poet. What is interesting about Poplavsky is that he has severed all ties with Russian subject matter. He is the first émigré writer who lives not on memories of Russia, but in a foreign reality. This evolution is inevitable for the whole of the emigration. [D. S. Mirsky (Prince Dmitry Svyatopolk-Mirsky), in Eurasia (Evraziia), Paris, 5 January 1929.]

…Poplavsky’s pseudonaiveté and sleek imitation of the correctly grasped literary fashions. There is no point in mentioning Poplavsky’s name next to the names of Blok and Rimbaud (and yet this has been done by Weidlé and Adamovich and Mochulsky). The scribblings (pisaniia) of Mr. Poplavsky, whose critical articles are as deliberately insolent as his verse, would not even deserve mention were it not for the fact that these puerile and shrill scribblings found an echo in Georgy Adamovich. [Gleb Struve in Russia and Slavdom (Rossiia i slavianstvo), 11 May 1929; 11 October 1930.11].

Gleb Struve attacked Poplavsky’s work vehemently when it first appeared in print, and he remained Poplavsky’s most consistent critical opponent. The only other adverse response to Poplavsky’s literary beginnings in émigré criticism, Vladimir Nabokov’s review of Flags in Rul’ [The rudder]—which Nabokov subsequently repudiated—is far milder in both its tone and its conclusions. Although Nabokov took Poplavsky to task for his violations of meter, ungrammatical usages, and abuses of inappropriate colloquialisms, he ended the review with the admission that some of the poems in the collection “soared with genuine music.”

In his later history of Russian émigré literature, Professor Struve cites the highly favorable opinions of various important émigré writers and critics about Poplavsky’s poetry with exemplary scholarly objectivity; he even seems to see some promise in Poplavsky’s novels. But his ultimate judgment on Poplavsky can be summed up in this quote: “He was a gifted man and an interesting phenomenon, but he never became any kind of writer, no matter what his numerous admirers may say” (Struve, Russkaia literatura v izgnanii, 313).

Exhibit G:

THE TRAGIC DEATH OF THE POET B. POPLAVSKY

The lower depths of Montparnasse have claimed the lives of two more young Russians. Under circumstances that are still being investigated, the poet Boris Poplavsky and nineteen-year-old Sergei Yarko, well known in certain shady cafés of boulevard du Montparnasse, died of narcotics poisoning.

ACCIDENT OR SUICIDE?

The police commissioner of the Maison Blanche quarter immediately initiated an investigation. At first, the possibility of a double suicide was not ruled out. But upon examination of the evidence, it became clear that the young men were the victims of a drug overdose. It is also possible that the drug, purchased on Montparnasse from nameless dealers, contained an admixture of some kind of poison.

Boris Poplavsky never thought of suicide. Sunday evening he visited Dmitry Merezhkovsky and discussed literature and politics with him. On Monday he was seen on Montparnasse. His parents, with whom he had a conversation several hours before his death, categorically reject the possibility of suicide. Their son was a victim of “white powder” vendors.

Apparently Poplavsky and Yarko had been addicts for a long time. In the poet’s wallet, his own photograph was found, bearing a revealing inscription: “If you are interested, I found a source of cocaine, etc. Reasonably priced: heroin 25 fr. a gram, cocaine—40 fr.” This was written in Poplavsky’s hand—apparently in some café, where he was not able to announce the news out loud to his friend.

NO FUNDS FOR BURIAL

At 4 p.m. yesterday, Poplavsky’s and Yarko’s bodies were taken to the Institute of Forensic Medicine for autopsy. The funeral is planned within the next few days. But there are absolutely no funds available for Boris Poplavsky’s burial. His family is destitute. There is not a sou in the house. Boris Poplavsky’s parents are appealing to all his friends and to all generous people to help them pay for a coffin and a burial plot for the poet whose life ended so tragically. Donations may be sent to Latest News.

[Selected passages from the lengthy news story in Latest News (Poslednie novosti), Paris, 11 October 1935].

Excerpts from “The Book of Blessings,” Poplavsky’s Unpublished Journal for 1929.

109. I need only those writers whom I can apply practically in my life, from whom I can learn a particular form of pride or pity and, of course, whom I can develop and alter in my own way. Chekhov teaches me to endure in a special way, not to surrender, to hope, for in Chekhov there is much that is Roman, there is much of “no matter what happens,” of quand même. With Dostoevsky one can be ill and die, separate and perish, but it is impossible to live with him. As for Tolstoi, with his ancient Hebraic family idylls, I find him repulsive. But Chekhov I hope to put to use, after first rendering him harmless. How? By expanding and developing his admiration for the perishing, beautiful failures, by cleansing him of his disgusting squeamishness and his dignified contempt, contempt for what has failed, what has perished, i.e., extending him in a Christian or, more correctly, specifically Orthodox direction.

110. Chekhov is the most [Russian] Orthodox of Russian writers or, more correctly, the only Orthodox Russian writer. For what is Russian Orthodoxy if not absolute forgiveness, the absolute refusal to condemn which we hear in the voice of Sonya and of the Little Priest of the Swamps? [I.e., Sonya from Chekhov’s play Uncle Vanya, and the elfin creature from Blok’s poem of that name, who prays with equal fervor “for the injured leg of a frog and for the Pope in Rome.”]

111. Blok is also an Orthodox poet, the poet of absolute pity, angry at nothing, condemning nothing….

115. It seems to me that the closest work we have to the spirit of the Prometheus of Aeschylus is Chekhov’s Ivanov. Let us note, en passant, that the Prometheus of Aeschylus is one of the most pretentious heroes in world literature. But then, is there anything more beautiful than heroic pretentiousness, for is not the perishing hero higher than the smugly successful hero? And is not the point of a perishing hero in his pretense at being a hero?

116. All my poetry is only the voice of Sonya, or at least I would like for all my poetry to be the voice of Sonya, consoling Uncle Vanya abandoned by everyone in the midst of the demolished estate….

123. Oh, how the lower strata of the émigrés are irritated and outraged by the sight of an impoverished and merry friend of books and stars, with his tattered pants and a monocle in his eye! It is their enormous, base yearning for power that is outraged within them. What! He dares to be joyous, that owner of worn-out shoes? Isn’t he in the same position as we? He has no money, no power, and he dares to be joyous. Where does he get his joy? Surely not from that bookish, intellectual stuff—the very thing that ruined Russia? From Culture and Social Conscience? Thus the poor people. And a huge disgust hangs suspended in perplexity from their curled lip, while the friend of the stars goes his own way in his worn-out shoes, waving his handsome athletic arms in the air as he recites poetry to his neighbor.

124. The attitude of the wealthy émigrés toward the friend of the stars is even more base. What! We’ve done our best, we’ve achieved, we’ve recovered our own, and this one dares to be joyous while the seat of his pants is in patches? What was the point of our struggle?

125. But the attitude of foreigners is delightful. It can be seen from their glances in the street, for in them there still survive the ancient, beautiful ideals, merry and profound, of ancient stoical poverty. There was once this delightful philosopher—Anaximenes of Dorcrete seems to have been his name—a fine athletic old man. Diodorus tells us that he was once invited to some ritzy party, by some tyrant or other. Coming to the table, he bared himself and beshat the company and the table, and with this excellent deed he indubitably deserved his immortality. His other works were forgotten, but compared to this they could not have been important.

Poplavsky Yesterday and Today

When I first read Flags, I had no idea of Poplavsky’s position in the Russian literary hierarchy. I had simply assumed that he was a poet as famous as Blok and Pasternak. I knew little about Russian poetry as a whole at the time, and there were many important modern poets I was yet to discover and read. It took me a few years to realize that apart from a small cult centered in Paris, almost no one had ever heard of his name. In the late 1940s my colleagues at the Control Council for Germany, Alain Bosquet and Edouard Roditi, were publishing a literary journal in Berlin. They asked me to write something about Russian poetry for it, “about somebody modern and famous, like Selvinsky or Bagritsky,” as Roditi put it. I had no idea who Selvinsky and Bagritsky were, but I offered to write about the three poets who had been my favorites during my school years in Los Angeles. They let me, and I wrote three brief pieces on Khlebnikov, Pasternak, and Poplavsky; these were translated into German and published in Das Lot in 1950, with a selection of translated poems by each of these poets. [S. Karlinsky, “Drei russische Dichter,” Das Lot 4 (October 1950): 46–51].

The overindulgent accompanying note identified me as the author of “numerous articles published in American newspapers and magazines,” but apart from a few pieces in the college newspaper, this was actually my debut in print. I’m glad it had to do with Poplavsky and that I already then called him the most interesting poet produced by the Russian emigration between the two world wars.

By then I had already read his two posthumous collections of verse (they contain some astounding poems, but I found them on the whole a bit of a letdown after Flags); the published portions of his novels (Homeward from Heaven contains some of his finest lyrics, inserted between passages of prose and printed to look like prose); his paradoxical critical essays; the highly original short story “The Ball;” his pieces on painting and boxing.

When in 1965 Nikolai Tatishchev privately published a new volume of Poplavsky’s previously uncollected poems, Dirigible of Unknown Destination, my torch for the poet flared up again. The volume contained some of his most typical and most perfectly realized poems (“On the Frontier,” for instance, with its striking central metaphor of a poet as a customs official trying to stop the two-way smugglers’ traffic between the Land of Good and the Land of Evil; or “The Biography of a Clerk,” with its transposition of the humiliated clerk of Gogol’s “The Overcoat” and Dostoevsky’s Poor Folk into a Kafkaesque and surrealistic tonality).

I read a paper on Poplavsky’s surrealistic techniques at a scholarly gathering in Washington, D.C., and published it as an article in Slavic Review. A few graduate students purchased copies of the Dirigible as a result, but I knew that, with one or two exceptions, I had failed to convince my fellow Slavicists of the value of Poplavsky’s work. Just how badly I had failed was made clear to me by one of my most respected and discerning colleagues, who referred to him as a Parisian Vertinsky (a popular émigré nightclub singer) for the elect few.

Doing literary research in Europe in the fall of 1969, I made a point of seeking out and talking about Poplavsky with those who knew him or were his friends in an effort to reconstitute the reality of the man behind the poetry and the prose: the poets Alla Golovina and Sofiya Pregel; the painters Ida Karskaya (a marvelously warm and compassionate woman and a far more important painter than I had previously realized) and Constantine Terechkovitch; the critic Georgy Adamovich; the literary scholar Sophie Laffitte (née Glickman, later Sophie Stalinsky and Sophie Bonneau); and of course Poplavsky’s closest friend and the curator of his archive, Nikolai Tatishchev. All of them had observed Poplavsky at close range at one or another time in his life, all but the first two had poems dedicated to them in Flags, and all were willing to talk about him candidly and openly.

Some day I hope to transcribe these interviews in full, but for the moment I can say that their sum total has helped me to formulate the two sets of polarities that I feel primarily motivated and shaped Poplavsky’s literary art. The never-resolved dichotomy between poetry and painting is what accounts for the intensely visual nature of his imagery and much of his subject matter.

According to Terechkovitch, Poplavsky thought of himself during his first few years of exile not as a poet but as a painter. In 1922, Terechkovitch and Poplavsky traveled together to Berlin to study art. In Berlin, Poplavsky met the leading Soviet abstractionists as well as Chagall, Tchelitchew, and Chaim Soutine. But everyone, and particularly his teachers and colleagues, kept assuring him that he had no talent for painting. At first he tried to ignore their verdict. When he realized that they were right, the result was a total nervous breakdown that kept him bedridden for several weeks. Not only his highly personal articles on art exhibitions and painters, which appeared later in the journal Numbers (Chisla), but much of his prose and poetry testify to his never-ending yearning for mastery of the visual arts. His literary development reflects not so much the development of Russian émigré poetry as the evolution of the Paris schools of painting in the late 1920s and early 1930s—especially those of the Surrealists and the neo-Romantics.

The other central polarity has to do with his insatiable hunger for mystical experience (any kind of mysticism) and drug experience (any kind of drugs). It was his sister Natasha, that “dazzlingly educated and talented girl” his father wrote about, who introduced Boris to drugs by the time he was twelve. Her search for the ultimate high eventually took her to Madagascar, to Africa, to India, and finally to Shanghai, where she died in the late 1920s—of pneumonia, according to her father’s biography of Boris, but of a hopeless opium addiction according to everyone else.

Drugs remained a constant presence in Poplavsky’s life, both in Berlin and in Paris, and they (rather than imitation of his idol Rimbaud) account for the psychedelic swirling of images and the vivid, violent colors so typical of his verse. There are vast riches of authentic psychedelia to be mined in twentieth-century Russian poetry—Balmont and Khlebnikov are the names that come to mind most easily—but no one in the Russian tradition exploited the openings to other realities that drugs afford as systematically as did Poplavsky in the service of his poetry. There was, unfortunately, no LSD or mescaline to be had in those days, and he had to do it the hard way. (A tremendous stimulus for writing much of Flags came when his friend, the minor poet Boris Zakovich, the “Pusya” of Poplavsky’s journals, inherited a large supply of pain-killers and mind expanders from his dentist father.)

Those who are capable of appreciating the unique kind of beauty Poplavsky was thus able to glimpse and convey are the beneficiaries. Poplavsky’s religious quest was as intense as it was eclectic. A devout and loyal member of the Russian Orthodox Church (as his journals leave no doubt), he was powerfully drawn to Roman Catholic rite and lore, to Hindu mystics, to freemasonry, and to various forms of spiritualism.

One of the most intense experiences of his life, according to Tatishchev, occurred in 1918, when he met Jiddu Krishnamurti, the philosophical and spiritual teacher, who took his hand and addressed a few words in English to him. Poplavsky understood no English, but he was moved to tears. In Berlin he had several discussions about anthroposophy with Andrei Bely. (His mother and aunt were close to Moscow anthroposophic circles.)

Boris Poplavsky was loved by a number of exceptional and brilliant women in his day, but the central relationship of his life, its keynote, was what he himself called his love affair with God (roman s Bogom). This affair is the subject of many poems in Snowy Hour; it is basic to his novels, and it is vividly reflected in the portions of his diaries which his friends Dina Shraibman and Nikolai Tatishchev published after his death. It was also discussed in print by no less a thinker than Nikolai Berdyaev in his puzzled, perplexed, and not entirely sympathetic review of Poplavsky’s journals [In Sovremennye zapiski Contemporary annals, no. 68 (1939)]. I’ll venture to say, with all due respect, that the celebrated philosopher simply failed to grasp the point of Poplavsky’s mysticism. Like art, like drugs, mysticism was for Poplavsky both a way of expanding his personal vision and a means of transforming unbearable social reality.

Poplavsky’s lecture on Marcel Proust and James Joyce (he is the only Russian writer I can think of besides Vladimir Nabokov who responded creatively to Ulysses), of which I have the outline, concludes with a surprising prediction of impending social revolution in Western Europe, which would combine social, sexual, and personal-mystical elements. For Poplavsky, the reason the Soviet experiment turned Russia into a “vast, barbarous, snow-clad field” was that in its attempt to build a better society it suppressed the human spirit and its most precious manifestations. This was well understood by Poplavsky’s friends Zinaida Gippius and Dmitry Merezhkovsky; yet one can easily imagine the shock that this conclusion of the Proust-Joyce lecture occasioned among the émigré audience when Poplavsky delivered it at the Kochevie Club on 22 October 1931.

Poplavsky’s career in the world of émigré letters was brief and meteoric. Only six years separate his literary debut from his death. During that time he impressed some of the most important older writers-in-exile (Merezhkovsky, Khodasevich, Georgy Ivanov) and was acclaimed by the finest émigré critics (Mirsky, Mochulsky, Adamovich, Weidlé). He must have made an enormous impression on the émigré writers of his own age group, for he looms as a momentous presence in the subsequently written autobiographies and memoirs of Nina Berberova [The Italics Are Mine (New York, 1969)]; Yury Terapiano [Vstrechi [Encounters] (New York, 1953)]; Vladimir Varshavsky [Nezamechennoe pokolenie-The unnoticed generation (New York, 1956)]; and V. S. Yanovsky [“Eliseiskie polia” [Les Champs-Élysées], an excerpt from his memoirs, in Vozdushnye puti: Al’manakh [Aerial ways: An anthology], vol. 5 (New York, 1967), 175–200].

Vladimir Nabokov on two occasions singled out Poplavsky as the only poet of importance among the younger émigrés.20 At Poplavsky’s funeral, homage was paid to him by such diverse figures as Mark Aldanov, Aleksei Remizov, and Vladislav Khodasevich, whose eloquent obituary of Poplavsky was later reprinted in a collection of his critical essays [V. Khodasevich, “O smerti Poplavskogo” [On Poplavsky’s death], in Literaturnye stat’i i vospominaniia [Literary essays and memoirs] (New York, 1954)].

And yet, if we were to take a count, there would probably be fewer people in the world today who are aware of Poplavsky’s existence than there were in 1935. I am convinced that Boris Poplavsky has his readers somewhere. But where? Russians, either abroad or in the Soviet Union, don’t seem to want to read him. When Olga Carlisle included Denise Levertov’s fine translation of his poem, “Manuscript Found in a Bottle,” in her book Poets on Streetcorners, the Moscow Literary Gazette took her to task for including this “tramp of whom no one has heard” among the other fine Russian poets in her anthology.

Publication of a few excerpts from The Apocalypse of Therese in George [Yury] Ivask’s Russian literary journal Experiments (Opyty) in the late 1950s was met with similar scorn by Russian newspapers in Paris and New York.

I tried submitting several of his unpublished poems and a highly interesting essay on Russian painting (which I obtained from Nikolai Tatishchev and which Jean-Claude Marcadé carefully annotated) to the New York Russian literary journal Novyi zhurnal. Two of the poems were published, with distorting “corrections” by the editor, while the remainder of them and the article were rejected after a two-year wait. [An English translation (by Peter Lawless) of Poplavsky’s article about the Berlin Exhibition of 1922 was eventually published: “The Notes of Boris Poplavsky,” intro. by Simon Karlinsky, annotations by Jean-Claude Marcadé, Art International 18 (1974): 62–65].

In a personal letter to me, the editor of Novyi zhurnal, Roman Goul, wrote that Poplavsky was “an utter madman” and proudly recalled how he and a group of friends once threw Poplavsky out of a Berlin beer hall.

And yet, as Vladimir Nabokov put it when I informed him of my interest in Poplavsky: “Yes, write something about him. He was, after all, the first hippy, the original flower child.” This might simplify things a bit, but it is not wrong. [His involvements with drugs and Hindu mystics are two of the more striking ways in which Poplavsky seems to foreshadow the hip culture, but that is by no means all. He dressed unconventionally, was never without a pair of dark glasses, thought bathing unnecessary, and would wear the same shirt for weeks on end. His favorite music was by Bach, Scriabin, and Stravinsky. A beard and long hair are the only ingredients that were missing, but that tonsorial style was inextricably connected with the priestly caste in Russian culture. There clearly would have been no point in Poplavsky’s trying to pass for an Orthodox priest.]

During the past few years young Slavic scholars in the West, those in their early twenties, have been repeatedly taking to Poplavsky like the proverbial duck to water. I’ve read with pleasure the intelligent papers Olga Bazanoff and Mike Hathaway wrote about him for Vsevolod Setchkarev’s seminar on émigré literature at Harvard, and Hélène Paschutinsky’s first-rate MA thesis on Poplavsky’s imagery, written under Sophie Laffitte’s direction at the Sorbonne. I am excited about Anthony Olcott’s Stanford thesis.

[Particularly impressive is Mlle Paschutinsky’s demonstration of the central function of the states of flying, floating, and levitation in Poplavsky’s poetry, and of his systematic use of objects and beings capable of these states: fish, ships, dirigibles, balloons, submarines, interplanetary rockets, clouds, comets, and angels, as well as the role of Poplavsky’s ubiquitous bridges, balconies, and towers, functioning as steppingstones to flight and levitation. The resultant antithesis of lightness and heaviness is then used by Mlle Paschutinsky to construct a highly convincing and logical system that provides us with a key not only to Poplavsky’s imagery, but also to the whole of his complex metaphysics. Should Poplavsky’s poetry ever gain the wide readership it so very much deserves, Hélène Paschutinsky’s study will certainly be a fundamental source on this poet.

[In subsequent years Paschutinsky, under the name of Elena Menegaldo, published widely on Poplavsky. See, for example, her important edition of Boris Poplavskii, Neizdannoe: dnevniki, stat’i, stikhi, pis’ma, ed. A. Bogoslovskii and E. Menegal’do (Moscow: Khristianskoe izd-vo, 1996), and subsequent editions of Poplavsky’s collected works. See also Dmitrii Tokarev, “Mezhdu Indiei i Gegelem” (Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 2011)].

Perhaps Poplavsky was an émigré in more senses than one. Caught between cultures, he was also trapped in the wrong historical period. Many young non-Russians today should have no trouble identifying with him and seeing him as one of themselves. As Emmett Jarrett and Dick Lourie wrote,25 when I sent them some trots of his poetry for translation: “He’s dynamite…”

How to detonate him?

It is of interest to read Karlinsky’s early publication—dating from 1950—which was written as an introduction to a German translation of three of Poplavsky’s lyrics:

Boris Poplavsky’s name is completely unknown in his own country. Poplavsky was perhaps the most gifted representative of a generation of Russian émigré poets who were born in Russia but whose literary activity between the two wars took place everywhere: from Warsaw to Addis Ababa. Poplavsky spent his short life (1903–35) mostly in Paris. His literary reputation was based on a small volume of poems with the title Flags. This book was published in Paris and Tallinn in 1931.

After his death, a collection of poems with the title In a Wreath of Wax, a short novel (Homeward from Heaven), and Diaries were found among his papers. A selection of these works was published by Poplavsky’s friends. In Diaries, Poplavsky gives a detailed description of his poetic method. In this context, Poplavsky quotes an old Hindu poem in which an unknown poet is not satisfied with the sentence “The tree of my life yearns on a hill;” a few lines later the same poet gives a modified version of the same sentence: “The blue tree of my life yearns on a hill.” As Poplavsky noted, the color blue is added to express the intangible.

Nowadays Poplavsky’s poetic method seems to be similar to French Surrealism, and Diaries shows that he had studied and admired the writings of André Breton. When reading Poplavsky’s poems one is reminded of surrealistic paintings.

[Translated by Joachim Klein, from S. Karlinsky, “Drei russische Dichter,” Das Lot 4 (October 1950): 50].

Simon Karlinsky (1924–2009) was a prolific scholar of modern Russian literature who taught at the University of California, Berkeley, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, from 1964 to 1991. This memoir is an excerpt from Freedom From Violence and Lies, a collection of Karlinsky’s essays.

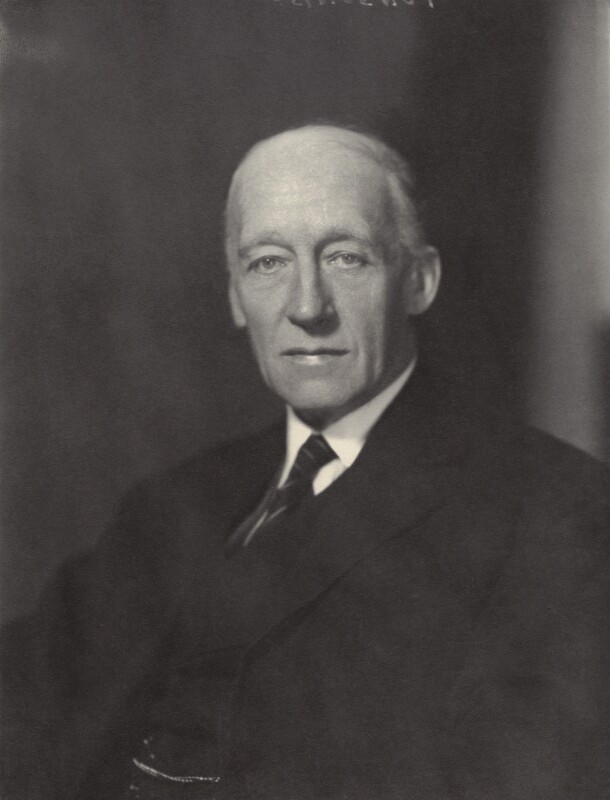

Featured: Boris Poplavsky, at KaDeWe (Kaufhaus des Westens, Department Store of the West), Berlin, 1922.