Through the kind courtesy of Regnery Publishing and Regnery Gateway, we are so very honored to present this excerpt from Professor Bruce Gilley’s recently published book, In Defense of German Colonialism, a tour-de-force of the great good that the German colonial effort achieved in Africa, such as economic development, the rule of law, good governance, and human rights for minorities and women.

In an insightful link-up with the present, Professor Gilley shows that the dismantlement of the German colonies enabled Nazism which, in turn, is the root of wokeness. Professor Gilley’s research is impeccable and his conclusions undeniable. Please support his valuable work by purchasing your copy of this intriguing and informative book. You will not be disappointed.

● ● ●

The Spirit of Berlin

Bismarck’s ironclad indifference towards the colonies cracked in 1883 when a failed tobacco merchant from Bremen named Adolf Lüderitz wired to say that he had run up the German flag on a thin strip of land on the Atlantic coast of southern Africa. Lüderitz had bought the land from natives of the Nama tribe for two hundred loaded rifles and a box of gold. The Nama needed the rifles for their ongoing wars against their historic enemies, the Herero. Bismarck at last gave in. Following his recognition of Lüderitzland (population twenty), Bismarck told the Reichstag that henceforth he would fly the flag whenever established German merchants requested the protection of the state. “We do not want to install colonies artificially,” Bismarck sighed. “When they emerge, however, we will try to protect them.” His hope was for empire on the cheap: “Clerks from the trading houses, not German generals,” would handle the functions of government.

Since Germany was a colonial newcomer, it had the neutrality to convene the 1884–85 conference to set new ground rules for colonial endeavors. Being sensitive to publicity, the Germans invited some Africans from the Niger river to join their delegation, at first calling them porters, then river navigators, then caravan leaders, and finally “princes.” Other European powers hastened to bring their own “loyal Africans” to wintry Berlin to demonstrate their own legitimacy.

During the meetings, Bismarck oversaw a major redefinition of colonialism. The Germans spoke most frequently and thus their views had tremendous influence on the final agreement. While the immediate issues were the Congo and West Africa, as well as free trade, the broader question was on what basis colonial rule could be justified. Initial fears that Bismarck planned to make vast claims on unmarked territory proved unfounded. His aim was simply to promote European trade in a way that did not bring the European powers to blows and that delivered uplift for the natives.

The Spirit of Berlin was embodied in two principles. First, colonial powers, whatever else they did, had a responsibility to improve the lives of native populations. European powers, the agreement stated, should be “preoccupied with the means of increasing the moral and material wellbeing of the indigenous populations.” When a colony was established, the powers “engage themselves to watch over the conservation of the indigenous populations and the amelioration of their moral and material conditions of existence.” That included putting an end to slavery and the slave trade. It also meant supporting religious, scientific, and charitable endeavors to bring the “advantages of civilization.” Bismarck praised the “careful solicitude” the European powers showed towards colonial subjects. Native uplift was now an explicit rather than implicit promise of colonialism. A British delegate noted that “humanitarian considerations have occupied a prominent place in the discussions.” Words only. But words that would create norms, and norms that would shape behavior.

The second principle insisted that any colonial claim needed to be backed up by “the existence of an authority sufficient to cause acquired rights to be respected.” Merely planting the flag or signing a treaty with local chiefs for a box of cigars was no longer enough. Colonialism required governance so that “new occupations . . . may be considered as effective.” This was later known as the principle of “effective occupation.” With this idea, Bismarck introduced the expectation that colonialism was not mere claim-staking or resource development—even if those things were still better than no colonialism at all. Rather, as with his newly created Germany, political institutions needed to provide the means to deliver the end of good governance.

The “effective occupation” principle applied at first only to coastal areas since the powers did not want to set off conflicts over border demarcations in inland areas. But as mapping of the inland proceeded in subsequent years, it crept willy-nilly into the bush as well. It “became the instrument for sanctioning and formalizing colonial occupation even in the African hinterland,” noted a legal historian.

One result of the Spirit of Berlin was a surge in trans-colonial cooperation among the major colonial powers. British, French, and German officials, especially in Africa, acted as if they were part of a common European project. They regularly swapped bits of territory, shared tips on governing, and got gloriously drunk to cement the bonds of colonial friendship. Germany’s top colonial official hosted a dinner to honor the retiring British governor of Uganda when they found themselves together aboard a homebound German steamer in 1909: “We made flowery speeches, vowing eternal friendship between our two nations,” the governor recalled. In German Samoa, the governor in 1901 appointed a Brit who did not speak German as the top official of the largest island. At the outbreak of war in 1914, the Brit was still expecting to draw his civil service pension from the British colonial office, arguing that European colonialism was a unified endeavor for the betterment of other peoples.

● ● ●

The Berlin conference has been subject to a relentless campaign of debunking by modern intellectuals. One claim they make is that the assembled delegates “carved up” Africa like a bunch of gluttons. This is wrong. For one, the carving was already happening when Bismarck acted. The conference was a response to, not a cause of, expanded colonial claims. Critics seem to think that absent the conference Africa would have been left untouched. Quite the opposite. The scramble for Africa created tensions, suspicions, and fears on all sides. Bismarck wanted to set some ground rules.

Second, if “carving up” is taken to mean staking territorial claims on a map with a view to gobbling up resources, this is flatly untrue. Of course, economic interests took a prominent role in colonial expansion as a way to pay the costs and reward the effort. But the attendant responsibilities were new. Expansion now required an explicit commitment to native uplift alongside economic development, and this commitment required the creation of effective governing structures.

Finally, the notion of “carving” conjures images of high-handed mandarins in Europe ignorant of local conditions absent-mindedly drawing boundaries on a map while playing a game of whist. The myth of “artificial boundaries” drawn by ignorant Europeans is one that dies hard. In fact, as the French scholar Camille Lefebvre has shown, colonial administrators went to great lengths to figure out where boundaries should be drawn. In doing so, they made use of extensive local knowledge. Later demands by critics to redraw borders along ethnic lines, she argued, “had the paradoxical effect of erasing the history of African political structures and the role of the local populations in defining colonial boundaries.” This reflected a racist idea “that the essence of Africans is to be found in their ethnicity.”

The final border between German Cameroon and neighboring British and French colonies, for instance, was the result of tortuous field surveys carried out with native guides between 1902 and 1913. “The boundary is, as far as possible, a natural one, but, whenever practicable, tribal limits have been taken into consideration,” a Times of London correspondent reported on the arduous demarcation, noting “no opposition was met with by the natives, who realize the advantage of having a definite chain of landmarks between English and German territory.” In German East Africa, the Germans allowed the neighboring British territory to control all of the lake between the two in order to protect native trading patterns. The treaty of 1890 also allowed that “any correction of the demarcation lines that becomes necessary due to local requirements may be untaken by agreement between the two powers.” Critics forget that drawing borders on a map would mean little if they could not be enforced, and enforcement in turn depended on local social and economic conditions.

What is true is that these political boundaries did not always coincide with ethnic boundaries. Many ethnic groups ended up on different sides of borders because carving up “ethnic homelands” would have been both impractical as well as, in Lefebvre’s view, racist. If there is a “high-handed” assumption at play, it is the assumption of later critics that Africans are essentially tribal and need to be organized on tribal lines. Thus borders should be redrawn not based on political, social, and economic logic but on ethnic essentialism. When the apartheid state of South Africa created such ethnic “homelands,” they were roundly derided because they created ethnic ghettos cut off from modern lines of economic and political life. Yet the “artificial boundaries” critique of the borders resulting from the Berlin conference is an appeal for just such apartheid-style “homelands.”

Broader criticism of the Spirit of Berlin is even more hyperbolic: no white man, German or otherwise, the critics avail, had a right to march around the world oppressing helpless brown and black people at gunpoint. One Harvard professor wrote that the British and French should be equally blamed for the rapacious Spirit of Berlin even though the Germans hosted the conference. There should be no Sonderweg or “separate path” theory that explained why only Germans were evil. Any suggestion of a “German (colonial) Sonderweg” would exculpate Britain and France from their fair share of the blame for the great evil that was European colonialism. Scholars like him censure as racist the idea that Western civilization had anything to offer to non-Western peoples. The so-called humanitarian principles of the conference were so much hypocrisy, a clever cloak for

self-interest, they charge.

Not one of these claims withstands scrutiny. Civilization is a descriptive concept that emerged in the field of archaeology to measure the progress that cultures achieved towards the universally common ends of intensive agriculture, urbanization, state formation, the division of labor, the use of machinery, civic government, and a written tradition with record keeping. If Europeans truly believed that black Africans were inherently inferior, why would they try to raise them up to European levels of civilization? It would be impossible. The assumption that European progress was accessible to all was based on a belief in the universal human potential of all peoples.

As to the inevitable coercion that this entailed against dominant local elites, critics forget important lessons from the past in their sermonizing. World history is a story of more civilized nations conquering less civilized ones because they are better organized and thus able to create and sustain more lives, production, and material wealth. Nowhere in the world at the time was it assumed that conquest was bad. Certainly, powerful African groups like the Fulani and the Buganda assumed they had a right to conquer nearby peoples. As Jörg Fisch wrote: “Strictly speaking, the colonial acquisition of Africa needed no justification. The Europeans had the necessary strength and, even within Europe, the right of conquest was widely accepted both in theory and state practice.”

Claims that no African was involved or that colonial expansion ignored African interests are rather bizarre given that such norms were alien to Africa itself. The Fulani, Buganda, Bantu, or Ngoni had not asked whether they should “consult” the African peoples they subjugated before the Europeans arrived. With the Spirit of Berlin promising high living standards, Europe’s conquest of Africa was justified, not just legally but also ethically, and just as much it was unavoidable. The idea that it was “arbitrary” for Western civilization to spread (or that such a spread was based on ill intent) simply ignores the fact that human societies all strive to be more civilized.

Civilization isn’t racist and violent; denying it is. Anti-civilizational discourses that wish upon non-European peoples a return to the five thousand–year developmental gap that they faced when the European encounter began deny the humanity of non-Europeans. These Woke theories embody the racism they decry. As the Canadian scholar Tom Flanagan asked in rebutting claims that the “First Nations” (Siberian migrants to North America) should have been left in their primitive state in Canada, “Though one might dislike many aspects of civilization, would it be morally defensible to call for a radical decline in population, necessitating early death and reproductive failure for billions of people now living?”

The “civilizing mission” was both proper and reasonable as an aim of European colonialism. Germany more than any other colonial power took that mission seriously, as shown by its extensive training academies for colonial administrators and special institutes to understand native cultures, geographies, languages, and economics. As one American historian wrote:

Of all the European powers engaged in colonization in tropical territories before 1914, the Germans made the most extensive efforts in the direction of preparing themselves for their colonial responsibilities. Though their emphasis on colonial education had developed only late in the history of the German colonial empire, it was one of the determinants of their stature in 1914 as one of the most progressive and energetic of all the colonial powers.

In 1988, American historian Suzanne Miers claimed to have “uncovered” a dark secret about the Spirit of Berlin: the conference participants did not give a fig about the civilizing mission (an odd critique when set against the charge by others that they did, but that this mission was racist). Her evidence? The powers were also motivated by self-interest, and they did not try their hardest to enact their altruistic ends. Miers writes, for instance, that the British agreed to limit liquor sales in the Niger River region only “if all powers agreed to it, as, if they refused, British traders would be excluded from a lucrative traffic.” In the next sentence she states: “The Colonial Office certainly was not contemplating British self-denial for humanitarian reasons.” Yet her own sentence shows that they were contemplating this if it could be achieved. Like other scholars, she seems to think that Quixotic and ineffective romantic gestures are what was needed. Thank goodness the Colonial Office was staffed by men of practical bent.

None of this will convince colonial critics, of course, who hasten to point out that the abolition of slavery came slowly, liquor imports continued despite prohibitions, wars were fought using brutal tactics, and all the blessings of civilization like the rule of law, health systems, roads, and education came only piecemeal. Having set up a high standard, the European powers immediately fell short of it, thus “proving” in the eyes of the critics that they never meant it in the first place. Yet these critics never seek to establish what “best effort” would have looked like: What was fiscally, technically, and organizationally feasible circa, say, 1885, even if we wish away all political obstacles? A more accurate view, propounded by the Stanford economists Lewis Gann and Peter Duignan, is that Western colonial powers like Britain and Germany exceeded “best effort,” and the costs that this effort imposed eventually forced Europe to abandon the colonial project altogether.

Bruce Gilley is a professor of political science at Portland State University and the author of five books, including The Last Imperialist.

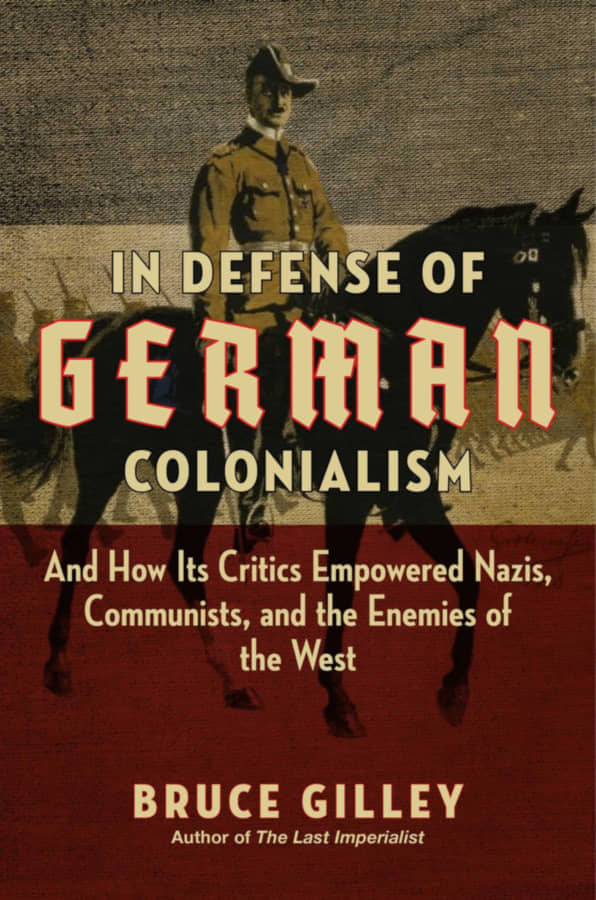

Featured image: a postcard from ca. 1910. Caption reads: “Our navy. ‘Take me across handsome sailor.'”