1.

When Queen Elizabeth II died the poorest people in the United Kingdom crawled out of their hovels in their dirty rags to join in solidarity with all those poor people who were still suffering from the yoke of colonialism in the undeveloped world. As one, they cheered that the source of all their suffering was finally gone—now, at long last, they could all live the free and prosperous lives that the Queen of the British Empire had denied them. YIPPEE… Oh, sorry, that did not happen.

If the lines of millions mourning her passing are anything to go by, there were plenty of outpourings of grief from her subjects, not to mention her own family who, for all the tabloid guff, are people. The grief of the living in their mourning is something that is a reminder of the fleeting nature of life on earth and what awaits us all. Irrespective of whether one is for or against the monarchy, it was a somber occasion, signaling the passing of an age as much as a sovereign, as much as a person.

Some people, though, are incapable of mustering even a modicum of decency in the face of death—they are the ones that generally show as little respect for the living as for the dead, though they often yell and scream as if they were the carriers of humanity’s better self, which is the picture that they have of themselves. And while there is a good case to be made that the monarchy as an institution in Great Britain may not last much longer, now that one of the most popular and dutiful of monarchs has died, the fact is that the Queen always displayed far more compassion, and respect for her subjects and their institutions than the members of that class that has successfully seized upon the moral imagination of the present, which it uses to denounce any relics of the past as well as anyone else that may obstruct the imperial ambitions of its authority. What they call diversity is merely division.

The Queen was indisputably vastly wealthy, but her life was one which few of us would like to lead. It required the kind of curbing of appetites and desires that few of us, and few in her family, were capable of—of devoting herself to a life-time, in which decorum and duty overrode everything else. This was authority and duty in the old style. She may not have been so flash on Derrida or Foucault, but her bearing and intelligence and character were all tailored to the position for which she had been groomed and which she carried out with grace.

Grace is not a word that comes to mind when I think of the new pro-globalists moralists that run the show now, in every Western land. They see the world as a great big trough which they will lead others to, provided they, in their role as liberators and representators of the oppressed, have their fill first. Anyone who thinks that their ideas are just verbal squish covering up their own sense of self-importance and ambitions to rule the earth alongside the globalist corporations and technocrats will need to be destroyed. Tyrants, as Plato rightly observed, are bred in the chaos of ultra-democratic aspirations and the accompanying social breakdown those aspirations create.

Just as their view of the present involves preferring abstractions (you know the ones, equality/equity/diversity/inclusivity/ emancipation, etc.), which have not been adequately tested in the reality of history, to see if they are of any more value than providing some kind of status of moral authority to the ones who use them—it takes these same abstractions into the past, and in finding that these abstractions were not there in any meaningful way is able to condemn the past as one of sheer oppression. Of course, the past they select to condemn is very selective: for the same class loves to create fantastical stories about premodern or non-Christian societies, as if they were just wondrous paradises of tolerance, diversity, equity and inclusion—from the world’s first and greatest democracy in Aboriginal Australia, where they would meet in their town-halls to make sure all was fair and square, to the wonderful multiculturalism of the Ottoman empire, with its pride parades.

It was primarily the members of this class of fabulists, who now control the Western education system and media outlets, who were predominantly using the occasion of Queen Elizabeth’s death to bang on about the genocidal history of the British empire and the role of the monarchy in general, and Elizabeth in particular. I do think the treatment of the native Americans in the USA in the nineteenth century might be described as genocidal; it was certainly absolutely shocking, but that was not the fault of the British empire, any more than the gulags were the fault of the Romanovs. But it did not matter to those tweeting their spittle about the Queen’s death that since the handing over of Hong Kong to the CCP in 1997 (something deeply regretted by the many Hong Kong locals I met in my eight or so years living there), Great Britain no longer has any colonies, while when Queen Elizabeth came to the throne in 1952 there were still over 70 colonies. Not that decolonization was an act triggered by the crown for, as everybody but those doing their celebration of spitting and drooling, seem to know, the British monarch while a de jure Head of State/constitutional monarch is de facto a ceremonial figure, symbolizing the nation’s unity—which to be sure is no easy feat in the divided area of the United Kingdom. In any case, her position requires her not intervening in political decisions that are the province of the parliament and courts. Thus, it was when there was a constitutional crisis in Australia back in the 1970s, and the deposed Prime Minister sought for her to intervene, she stayed right out of it.

In the United States, one of the first out of the blocks to drool and punch the air in celebration was the Nigerian born Associate Professor of Second Language Acquisition at Carnegie Mellon University, Uju Anya. She tweeted, “That wretched woman and her bloodthirsty throne have fucked generations of my ancestors on both sides of the family, and she supervised a government that sponsored the genocide my parents and siblings survived. May she die in agony.” The fact that, a few days after tweeting this bile, some 4000 other “scholars” publicly endorsed her (there must be far more by now), just goes to show what tax-payers and students are getting for their money.

From what I can gather, the slender threads of reality that Anya has woven into her fabric of verbal vomit and idiocy are that the British government supplied arms to the Nigerian government in their war against the secessionist attempt by the military governor of Nigeria’s Eastern Region, Lieutenant Colonel Emeka Ojukwu, in what turned into a horrific civil war. A mountain of literature exists on the war, though anyone who wants fair and brief appraisals of what occurred might read pages 199-205 (2011 edition) of Martin Meredith’s magisterial, The Fate of Africa: A History of the Continent Since Independence, or Margery Perham’s even-handed and first-hand account, “Reflections on the Nigerian Civil War” in International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944), vol. 46, No. 2 (Apr., 1970)., pp. 231-246.

In a manner befitting the moralizing, fabulizing, historically revisionist class of which she is a member, Anya fails to address the most basic of facts about her own country’s history: the French and Russians were also providing arms to the belligerents; that is belligerents on all sides were killing each other and seeking weapons from anyone willing to supply the same to them; the secession attempt by Ojukwu was a resource grab without any legitimacy that would have had disastrous results for Nigerians outside Biafra; Ojukwu’s propaganda game was as dangerous as it was vile as it was disastrous in its contribution to the mass starvation of the Biafran people that remains one of the most shocking famines in relatively recent historical memory. The chain of events which sparked the war and famine was ignited by Igbo military officers who assassinated key figures in the First Nigerian Republic. Finally, and to quote Perham, “the federal constitution of the three provinces, taken over by the Nigerians in October 1960 was largely the product of the Nigerians themselves, built up in intensive discussions and conferences, and attended by all the political leaders over a period beginning in the forties, and ending with the final conference of 1958. The basic differences between the main parts of Nigeria were not evaded: they were endlessly argued, but not even a dozen years of discussion and political advance, following half a century together under the canopy of British rule, could square the obstinate circlers within which deep and ancient tribalisms were enclosed.”

But who needs real political facts when you can become a mega-star in todays’ academic world with a tweet, so long as the tweet amplifies an ostensibly morally certain consensus, whilst confirming the moral superiority of all those, who also don’t need to actually know anything to know what they know, viz. that empires and colonialism are very, very bad? And no good person could ever be a beneficiary of empire—somehow, magically, the Nigerian born Anya, along with God knows how many of the other 4000 scholars, lives in the USA, reaping the benefits of office and wealth that come from what colonizers and their techniques and technologies of world-making have created.

This “logic” is the logic of the silly, who think that they can just arbitrarily go back into bits and pieces of history to select a point from which they can blame the people they don’t like—this time British imperialists. Sorry, but no people anywhere have been where they are forever. Which is partly to say the world is not a moral fabrication of bits and pieces all fitted together into a nice Disney movie about all the inclusion and diversity there would have been had it not been for… the British, the Germans, the Egyptians, the Greeks, the Romans, the Gauls, the Celts, the Abassids, the Persians.

Really folks! The world we inhabit is what people in their conflict, scarcity, cruelty, suffering, and everything else that has been done in the past have made. We are all respondents to a reality that precedes us and that we then work upon. Here, the moralists puff themselves up and splutter some kind of nonsense that has to do with their indignation that some people have killed more or suffered more…blah blah…than others. Let’s just say, we can’t undo the past, and pretending that we do by having reparations, etc. is just one more fantastical bit of fanaticism that is only a new way of creating work for a bureaucracy and moralizing class seeking ever more dependents.

In the case of reparations, they will mean nothing two generations down the track—but understanding that means thinking about economic behaviour, and human motivation and institutions, and the kind of thing that requires that rarest of things in today’s Tik Tok academic world—thoughtfulness.

This virtue stuff exhibited by people who are paid to denounce unequal things that obstruct universal emancipation is today’s electric Kool-Aid Acid of the moral imagination. Let’s face it, everyone has to earn a buck, and there is no easier way to do so today than by running around tweeting, screaming, teaching, or writing great big refereed academic tomes from illustrious brand name presses or densely footnoted articles in “prestigious journals” denouncing people who just won’t take out that part of their brain that enables them to see that all that stands between them and emancipation (which means—as far as I can see—having lots of sex and having lots of stuff) is their being subject to racist, sexist, colonialist blah blah blah ideas that scholars like Anya and her 4,000 mates (probably far more by now) think are “facts.”

So, I really can’t blame Anya; or, to pluck another from the media wing of the cathedral of woke idiocy, Tirhakah Love, a “senior newsletter writer for New York Magazine, who wrote, “For 96 years. That colonizer has been sucking up the Earth’s (sic.) resources,” and “You can’t be a literal oppressor and not expect the people you’ve oppressed not to rejoice on news of your death” for seizing the career opportunities made available to them by a ruling class whose rule is predicated upon destroying the shared norms, institutions and cultural achievements of the West in the name of the moral progress they embody, and the great future they believe they will bring into being—on the basis of which we can see already that would be a world of ever greater spiraling inflation, ethnic/tribal violence resulting from opening up “citizenship” to anyone who wants to live anywhere irrespective of criminal background, or commitment to any traditions of their new homeland; far more urban, racially based riots and burning of businesses, including black ones (to make way for gentrification); far greater crime (from burglary, shoplifting to murder), adorning inner city areas with tents for the ever-increasing number of homeless junkies; the redeployment of police resources away from crime prevention and into community development activities, such as flying pride flags and dancing in parades when they are not arresting racists, and homo-transphobes; schools in which critical race theory (whites are all the same—unless they teach critical race theory—and all bad), and the joys of the multiverse of sex and the importance of sexual rights, like the rights to change your sex as soon as you can speak are the main curricula; ever more spaces for public denunciations and ever more censorship; sacking of all who won’t do whatever the right-thinking authorities say they must do, say, or think; increasing the number of abortions up to and in the aftermath of an unwanted birth; ever more military interventions funded by you in the West for people outside the West to die in in far off lands that will save this great world from its nefarious enemies—and lots more butcher’s paper and crayons for “life-long” learning because learning to live in this shit will require that one remains a compliant imbecile during the entirety of one’s life-time.

2.

Bruce Gilley is a Professor of Political Science at Portland University—at least he was still there last time I looked, though it seems his existence is an affront to all the other good and virtuous professors who work there and who are doing their damnedest to push him into unemployment (the idea that professors could in any way be more virtuous than other people, and hence be tasked with instructing them in how to be better people, is something that, in a world less insane, would be worked into one of the more incredulous episodes of Curb Your Enthusiasm).

Bruce Gilley was once a highly respected scholar—with a dizzying number of academic prizes behind him—who once published books with such illustrious academic presses as the University Of California, and Columbia and Cambridge University. He burnt his bridges within the academic world with his essay “The Case for Colonialism.” The paper originally appeared in Third World Quarterly in 2017, having passed the blind refereeing process—a process that might give the delusion that the refereeing process in the Humanities and Social Sciences ensures academic quality and integrity—it doesn’t. But in any case those denouncing Gilley only care about referees who agree with them; and in the case of this essay, a petition of “thousands of scholars” and the resignation, in protest, of nearly half the editorial board of the journal, plus death threats being sent to the editor of the journal ensured it being “withdrawn” and given a new home.

Since the denunciations and attacks, Professor Gilley has written two books, both with Regnery Press—one can safely assume a university press will no longer touch anything he writes. His previous book, The Last Imperialist: Sir Alan Burns’s Epic Defense of the British Empire, before getting into print, underwent a similar saga. It was first going to be published by Lexington Books (an imprint of Rowman & Littlefield), where Gilley was also going to oversee, as the Series Editor, “Problems of Anti-Colonialism,” which would bring out books that sought “to reignite debate through a critical examination of the anti-colonial, decolonizing, and post-colonial projects.”

Then, the cancel crowd stepped in, started a petition on change.org: “Against Bruce Gilley’s Colonial Apologetics.” Many indignant “scholars” eagerly added their signatures. There was a counter-petition, which got nearly 5000 signatures, to try to save the series. But true-to-form, Rowman & Littlefield buckled and cancelled the series.

Eventually, Gilley found a far better home for his work—Regnery Publishing, which has also published his most recent book, In Defense of German Colonialism: And How Its Critics Empowered Nazis, Communists, and the Enemies of the West. This book does an excellent job of showing the ideological idiocy of those who are entrusted with teaching history to the youth of today, and who preside over the institutions which are preservers and now complete fabricators of a historical memory; that is to act as a foundation for future building.

Professor Gilley does not need my help in the shootout with the academy, as he takes down one “scholar” after another for preferring their ideological concoctions to the facts of the matter. But it is worth drawing attention to a few points that undermine not simply the ideological nonsense or inconvenient facts that derail the academic consensus which Gilley takes on with verve and astuteness, but both the role that the academy has adopted in ostensibly learning from the evils of the past to build a better future, and the mind-set that so commonly succumbs to preferring ideological simplicities and grand sounding nostrums to the far more complicated explorations which yield equivocations and hesitations in judgments about people who have had to deal with vastly different circumstances than those of our professional idea-makers, brokers, and overseers—as well as conclusions which one might not particularly be appreciated for reaching. That is, the study of real history requires being prepared to consider questions that transport one outside of a consensus that has been cemented because it was not driven by facts, historical or otherwise, nor by a well-considered and well-orchestrated series of questions, but by a priori “morally” and politically derived commitments which close off all manner of questions and hence understandings about reality.

History was among the more belated of the Humanities to fall into the kind of ethico-politics that took over Literary Studies for at least a generation.

In any case, working in the profession of “ideas” today involves little by way of having any virtue other than repeating and making inferences based upon certain moral consensuses and topics. One becomes a member of the profession of ideas by virtue of teaching and writing—the one exception in the doing is that increasingly universities have accepted the pedagogical value of political activism, if it is of the sort that conforms to the ethico-political ideas that have been accepted as true by those who write and teach on, and administer, the ideas which are to be socially instantiated. There are, to be sure, things one must not say (words or phrases one must not use) or do (at least to certain people with certain identities); but in the main not saying or doing those things is not remotely difficult, especially when the rewards are there for the taking, if one just goes along with things.

Just as character is a matter of irrelevance in today’s ideational configuration of identity, bestowing the right to a position, as a representative of one’s favoured disempowered group, being committed to a group narrational identity, has professional currency. Being an identity is to today’s mindset; what intelligence and character used to be. Neither of the latter are particular important anymore, as intelligence is dumbed down to the level of the school child, and character dissolved into an identity feature.

Today, our morally-fuelled anti-colonialists are condemning something that is now totally safe to condemn because it is no longer a reality that has any other part to play in their world than a moral occasion for their career advancement as talking moral heads. Being a part of today’s educated/ educational “leadership” brings with it all manner of predispositions and circumstances, and they are not ones that have anything remotely to do with what people who signed onto the foreign service or civil service in the age of colonialism, or even the academy some sixty or so years back, had to do.

People of different ages are pushed and pulled by different influences and priorities—and in so far as most young people are swept into whatever activities are part of the streams of opportunity, approval, ambition and mimetic desire that defines them, the difference between the youth who were caught up in the colonial enterprise, the revolutionary enterprises in Russia or China, or liberal progressive Wokeness today is not so much in their emotional enthusiasm and certainty, but the specific enterprise that has been socially and pedagogically concocted by the preceding generation and the opportunities that they grasp.

One can definitely identify which elites and which nations fare better by their doing; but so much of the doing is based upon what was made by previous generations, and who did what with the opportunities they had, as well as how much overreach and wastage occurred. Yes, I do think the elite generation of the West are more imbecilic and less charitable and capable of understanding the world and the circumstances that have made it and what is required to sustain a civilization than the elite that spawned colonialism. All groups have their blind-spots, and pathologies (here I am an unreconstructible Aristotelian) and the elites of the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth century are not beyond criticism—no group is, because no group and no one can see exactly what they are doing, nor have all the information that would help their doing—but to dismiss them all as racists and plunderers is to be shockingly ignorant about their intelligence, moral sensibilities and motivations.

In any case, the various reasons that were involved in decolonization, including their excessive cost, an increasing lack of support on the home front, and the aspirations of an indigenous elite and rebels calling and /or fighting for national independence, were not events that had anything to do with the academics of today who contemplate colonialism as a moral problem with a very simple answer—it’s really bad.

Our time is not one in which colonialism offers any kind of desideratum at a personal, social or political level. Which is also to say the academic who writes critically about colonialism today is doing about as much to stop colonialism occurring now as their writings have to do with preventing a reconnaissance mission on Venus.

Of those teaching in universities who have fought for wars of independence who are still alive and who might hold a job in a university or in the media, the kind of questions raised by Gilley then come into play, viz. did things fare better once there was “liberation?” The answer to that will depend upon many things—who the colonizers were and what they did, and what transpired afterward.

Having taught in Darwin (Australia), I met a number of people who had fought against the Indonesians to create an independent East Timor/Timor-Leste. The results in Timor-Leste are mixed, though it is very poor; and while there are issues of corruption, it is stable. For their part, the Indonesians were, to put it mildly, not loved by the locals. The fact that the Indonesians occupied it after they had liberated themselves from the Dutch only goes to show that yesterday’s colonized can readily become tomorrow’s colonizer.

The question of how a country fares after colonialism is a serious one, and in some places the results have been horrific. It was the existence of such cases, of which there are many, with Cambodia winning the prize in that department, closely followed by a number of African nations like Uganda and Congo, that makes an article, such as Gilley’s case for re-colonialism, worth considering. But it is a far better career move to hate on Gilley by people who would rather ignore any facts which might complicate the founding passage of post-colonial scripture that the ‘white-colonialist devil’ is the demiurge responsible for all the post-colonial violence that occurs, and the formerly colonized are either angels of light and liberation, or zombies created by their white masters.

Gilley’s article is short enough for me not to have to repeat its contents. I will simply say that Gilley was trying to make serious recommendations about how recolonizing might be a better option in some places than continuing in the same way. That is the kind of idealism/thinking by design that I genuinely eschew, but as a thought experiment it deserved better than the accolades of denunciation it garnered. And had his critics taken their heads out of the sack of Kool Aid Acid, they might have realized that Gilley does not argue for reconquering territory, but for investment with legal/sovereign strings attached being undertaken in areas desperately in need of economic and social development.

My problem with this is that just as the anti-colonialists in Africa were often educated in the West, where ideas about how great communism and such-like started to abound and were commonplace in the 1960s, now what the Western mind offers would be even worse. The re-colonizers would be operating with their ESG and their DEI commitments and targets—they would be saddled with green energy goals, which would make sure they stay poor, and be expected to buy electric cars, otherwise keep on walking; their kids would be schooled in critical race theory, so they could blame everything that goes wrong on white people, and gender-sexual anatomy fluidity to break up the traditional family and anything else that the elite running corporations have seized on to incorporate into the great new world.

The new mental imperialism promises nothing but the endless division and persecution of anyone out of step with the ideology that ensconces Western liberal progressivism as the global norm. The clientelist assumptions and strategies which make of our professional ideas-people the emancipators of all and sundry who are not white, wealthy, cisgender men, who don’t support the globalist political left/progressive technocratic view of life being transposable to any circumstance, including that of people who live in former colonies, who only have to sit down and read their various primers on Fanon, or study post-colonial fiction and poetry, etc., along with Judith Butler to see how they can fix up their world, and get to the same standard as, say, a San Francisco tent for the homeless with free crack.

3.

Much of what Gilley says in his article has been said by others, his “mistake” was to say it straight and assemble it into a formulation that exposes the thoughtlessness of the modern ideological consensus about colonialism. More broadly, though, the thoughtlessness that Gilley is dealing with is not just about colonialism, it is about how the world has come to be the world that is. Colonialism is certainly one part of that, and it is what concerns Gilley.

But if we take a step back from colonialism (and it is this that also distinguished, as Gilley notes, the “pro-colonialist” Marx from the “anti-colonialist” Lenin), two further considerations about the world are particularly pertinent, if we want to free our minds from the enchainment of stupidity that is presented as some kind of moral progress which is due to the purity of thought and being of our contemporary pontificating paragons. The first is where violence and war fit generally into the schema of human things. The second is technology (including the division of labour it requires—one of Marx’s better thoughts was to see the interconnection the division of labour, i.e., classes and technology; and like all Marx’s better thought, Marxists have abandoned it), and administrative technique.

With respect to the first, warfare is a perennial feature of human existence. The reasons for any given war may vary, but to blame war itself on one particular group is ridiculous. In the context of colonialism, warfare was pertinent to colonialism at every level of its development—from the wars that were commonly occurring between rival groups that colonialists were frequently able to use to their strategic advantage, to the wars between and against colonial powers that led to the demise of empires and their colonies.

That wars would continue after colonialism would only surprise those who think that merely deeming war a bad or an immoral thing might somehow play a role in preventing it. But while I find pacificism to be a response to war akin to when my cat thinks that if he cannot see me, I cannot see him—so he hides under a stool with his back to the wall and tale sticking out right under my nose—I find even more abominable the moral cherry-picking that poorly informed academics make about which violent conflicts they choose to take a stand on, without concerning themselves too much with all the forces and flows that go into it—thus, in general, their tacit support for the NATO proxy war in Ukraine.

A general, and hence, to be sure, not overly helpful formulation about why wars occur is that competing interests, predicated upon ways of being in the world and making the world, go to war when they see no other way to get what they want—in the past, more often than not, that was acquiring or protecting scarce resources, including labour power. Modern commerce does not necessarily prevent war because some resources are such that access may be unreliable or so tenuous that conquest is the more certain way to acquire them. But international trade is often the more secure way to acquire wealth. Of course, the moral imagination of the modern academic is not slow to critique capitalism. But as with violence and war, it cherry-picks which kind of capitalists are bad and who it serves (finance capital/big tech/big pharma are now its major “masters”)—it also comes up with fudge-words when confronted with the truth that socialism was no less murderous—and generally resulted in even more poverty—than capitalism, though state apparatuses and the elites who run them do make a very big difference as to whether capitalism can be even mildly benign.

Just as there is no genuine design solution to the problem of competing interests and life-ways, there is no simple design system that can eliminate war or class differences—though one thing that might ameliorate some of our problems is that groups have more thoughtful and well informed sources of information and representation, so they might be able to broker their differences from positions of strength (which in turn requires discipline in what is done with resources, how they are channelled in terms of strategic priorities, and who is fit and able in applying them).

But sadly, we have handed over the minds of our public and private institutions to a class of people, in the main, with ambition and enterprise existing in inverse relationship to the ability to think through alternative scenarios and consequences.

Irrespective of how one “parses” the moral behaviour and qualities of any group in conflict with another, and while just war theory may have an illustrious history, it has become a standard go-to position of idea professionals, whose sense of justice can be traced back to their own magnanimity—the fuse of most wars is woven out of various complex threads that go a long way back and have their own “reasons,” which is why a new party of force may take advantage of older animosities between groups to leverage its new authority.

Imperialism and the establishment of colonies are ancient ways of doing power that involve war; and any suggestion, whether tacit or outright, that suggests that there was something uniquely immoral about British imperialism or modern European colonialism is a fantasy.

The question of what benefits or costs were associated with any given empire or colonialisation project can only be answered by sitting down and doing the calculating. At some point, one might find that certain behaviours fit into some kind of moral calculus—such as Spaniards ending human sacrifice in the Aztec empire, or the British prohibiting the practice of widow-burning (sati) in India; or one might count the number and scale of massacres and ethnic and religious rivalries and wars committed during the reign of a colonizing power with those that occur previous to or after their reign. In the latter case, no matter how heated someone wants to get about the violence of the British in India, none in their right mind could think that the scale ever remotely approximated the scale of violence of the Partition (1947), or the subsequent war of Bangladesh.

In any case, and in any given colonial or imperial venture, there will be all manner of pluses and minuses that could be calculated, and there will be some beneficiaries and some losers. The point here, though, is that any fool can say that any imperial or colonial endeavour of yesterday is immoral—but the reasons for the endeavour were as much the reasons of yesterday as were the morals of those who undertook them. We might well be thankful that we do not live in such times with such choices or moral consensuses—all well and good, but so what? A strictly moral account of any given society is always going to turn out negative—life is frequently one tragic set of choices after another—which in part is why our educated elite can keep getting away with the nonsense of the air in their heads and the smoke of their words seeming more beguiling to youth and know-nothings who believe that all we have to do is “reimagine” the world to get the world we want—one of endless stuff and sexual pleasure—yippee!

While Gilley, citing pertinent writings and speeches from Bismarck, makes a case for Germany’s colonial enterprise being largely driven by extra-commercial incentives, in the main I think it difficult to un-entwine benign moral intentions of those with authority from opportunity for cads and bounders that may exist in the new colonies—though, my point is equally that wherever you go and whenever you went there was always some lot extracting stuff from and being cruel to another lot. Concomitantly, anti-colonialist forces often had to be as ferocious and cruel against those who did not find the new aspiring hegemonic elite to be serving their interests, as they were against the colonialists whose resources and power they wished to capture.

If the point I have just made emphasizes the eternal return of violence/ war/ opportunity/ authority, the second point, I think extremely important, is the unique nature of the technological and technocratic levels of advancement that occurred in the West, leading up to and culminating in the industrial revolution.

There are many aspects that we can consider to be definitive in the formation of the modern, but the industrial revolution makes any nation, in the position to take advantage of it, far more powerful than any peoples who are required to succumb to its authority. But, as Carroll Quigley convincingly argues in Tragedy and Hope, the industrial revolution is but one in a sequence of revolutions that occurred in the West; and the uniqueness of the West’s potency—as well as the problems it generates for itself and elsewhere—is intrinsically bound up with the sequences of its revolutions.

Here there can in my mind be no doubt that the world wars are the West’s creation, and I strongly recommend the little known book by Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, Out Of Revolution: An Autobiography of Western Man, which provides an account of the flow and circulatory nature of the revolutionary events which formed the peoples of Western Europe into the powers that would find themselves in the Great War and its aftermath.

But when the West is transported into other regions, such as its colonies, the powers that have been its revolutionary offspring come in a very different sequence and with varying accompanying problems.

I do not want to go into the different sequence of structural developments of revolutionary processes feeding into different and staggered modernities, but I do want to highlight the point that whether it was grace, genes, or the luck of the historical draw, or something else again that led to the modern West, once there was a modern West, and once there were modern weapons, and an industrial revolution, then class conflicts in non-Western countries played out along lines which have everything to do with resource-opportunities and competition and wilful determination by groups ready to use their arms to engage in the age-old act of resource extraction, from those who grow food to those whose labour can be put to use for them to expand the possessions and services at their disposal. One can morally condemn this all one wants, but it is a universal phenomenon that only passes by the intellect of people whose understanding of premodern life comes from Rousseau and Disney.

That is, once modern weaponry and machinery and the various goods they produce, from cars to tanks, designer clothes and luxury homes, smart drugs and high-class whores (let’s face it, the appetites of gangsters are as basic as they are commonplace among the extremely wealthy), exist, along with a group who are willing to do anything to get them, there will be an “enslaved” or violently brutalized class. That there will be tribal-elements involved in the social bonding is also pretty well inevitable (the Mafia and dynasties follow a similar logic).

This situation, to repeat, is not the result of colonialism as such but of modernity. And modernity brings with it a reality in which the choices are as inevitable as they are terrible: join it or don’t join it. Any group that opts out of joining makes itself vulnerable to any group with weapons who wants to encroach upon its territory, its resources, its labour, and its women. Further, the longer the delay in joining it, the more difficult it will be to adapt to what to a traditional life-way is a massive juggernaut of technologies and techniques exploding its fabric.

This is why the greatest enemies of the traditional life of the most vulnerable of social groups on the planet, the indigenous peoples who had not formed cities and/or larger units of social organization, were not missionaries or colonizers of the nineteenth century but the progressives of today who purport to ally themselves with anyone against Western supremacy, but who are, in fact, anti-traditionalists, Western supremacists, who have ditched anything that grounded the West in those pathways of life shared by all peoples.

Irrespective of the time of “joining” with a life-way of a superior power, and irrespective if the joining is one of choice or conquest, any group that joins in the process of modernization will find that it has to compromise/adapt its traditions and behaviours to the juggernaut. Seen thus it is hard to see how colonialism itself can be blamed for the choice. It isn’t responsible for that choice. Though our ideocrats tend to think that every problem is merely a matter of educating moral reprobates, which seems to be working out swell in US inner cities, where all manner of crimes go unpunished, and levels of violence and criminality are plummeting—NOT. Why not, though, try exporting a batch of critical race theory books to those areas where post-colonial gangsters and dictators—sorry victims of colonialism—now extort and kill others so they can wake up and see the light and go back to college, perhaps even one in the USA, and learn how to teach critical race theory and so be part of the great love fest that the new moral leaders of the West are creating.

But let’s get back to reality—colonialism might better induct the colonized into the means and manners required to live with the machinery and technology, and administrative and various systems that are being introduced into this world that cannot escape modernity—to repeat, because if it is not introduced by the colonizers, it will definitely be introduced by those “industrious” enough to get hold of the equipment and weapons that they can put to use. This is where Bruce Gilley raises important arguments, and why the reaction to him only illustrates what a mind dump the academy is, as it disseminates fantasies, moral and not so moral, about the world and its history so that it can enable a technocratic infantile future, as bereft of knowledge and wisdom, as it will be bereft of real love, and creative and cooperative endeavours.

I have already made the points that I wish to emphasise about modern colonialism needing to be interpreted against the constant of human conflict nd the tragic choice placed before any premodern people. I do think that life is ever one in which we are born into the sins and transgressions of our fathers; which is to say, I think Greeks and Christian were essentially correct and in agreement about the kinds of limits we confront, and that the modern elite aspires to throw away those limits and does so by substituting fantasies about the past as well as the future to beguile us into their nightmare.

But there can be no doubt that the modern opens up previously undreamt-of technologies and techniques which are amazing, and which enable the possibility of greater comfort and opportunities to do things for those that can get access to them. Thus, it is inevitably the case that any people who are conquered by a technologically superior people, if not completely turned into slaves, will benefit from the materials now available to them. We might call this the Monty Python/ Life of Brian argument for colonialism. To put it briefly: What have European colonizers ever done for the World? Answer: they brought with them the modern techniques and technologies of wealth creation. And the absence of those techniques and technologies is lower life expectancy and, in terms of sheer numbers, less wealth and less social choices.

Of course, in any society not everyone is or was a beneficiary of new social or technological innovations, and in every society the number of poor is significant—and prior to the industrial revolution poverty was far greater, and far more people were far more vulnerable to unfortunate climate conditions. And let us be real, at a time when there is so much panic about climate change, the fact is that any future famine, as with a number of past ones, will be far more likely due to political conditions than climate alone. At a time when the Malthusians run amok and aspire to dictate how the world should be depopulated, there is less global poverty and food shortage than ever; and where it does occur, politics and corruption rather than climate or population are the primary causes.

4.

The points I have made above are general, but if I were to recommend one book that any reader wanting to consider a test case, which refutes so much of the moralising that is done about colonialism should read it would be Gilley’s In Defense of German Colonialism: And How Its Critics Empowered Nazis, Communists, and the Enemies of the West. The Postil has already published a short extract from it; but that extract did not indicate the extent to which Gilley exposes and successfully critiques the thoughtless claims that academics have made about German colonialism—or, in his (un-minced) words, “the drivel that passes for academic history” about German colonial history.

Early in the work, Gilley makes three points about colonialism in general, which are worth repeating and the antithesis of the kinds of facts that get in the way of a good moral fantasy. I will quote them:

“Islands offer an almost perfect natural experiment in colonialism’s economic effects because their discovery by Europeans was sufficiently random. As a result, they should not have been affected by the ‘pull’ factors that made some places easier to colonize than others. In a 2009 study of the effects of colonialism on the income levels of people on eighty-one islands, two Dartmouth College economists found ‘a robust positive relationship between colonial tenure and modern outcomes.’ Bermuda and Guam are better off than Papua New Guinea and Fiji because they were colonized for longer. That helps explain why the biggest countries with limited or no formal colonial periods (especially China, Ethiopia, Egypt, Iran, Thailand, and Nepal) or whose colonial experiences ended before the modern colonial era (Brazil, Mexico, Guatemala, and Haiti) are hardly compelling as evidence that not being colonized was a boon.”

And,

“Colonialism also enhanced later political freedoms. To be colonized in the nineteenth–twentieth-century era was to have much better prospects for democratic government, according to a statistical study of 143 colonial episodes by the Swedish economist Ola Olsson in 2009.”

And,

“These twin legacies of economic development and political liberalism brought with them a host of social and cultural benefits—improved public health, the formation of education systems, the articulation and documentation of cultural diversity, the rights of women and minorities, and much else. It is no wonder, then, that colonized peoples by and large supported colonial rule. They migrated closer to more intensive areas of colonialism, paid taxes and reported crimes to colonial authorities, fought for colonial armies, administered colonial policies, and celebrated their status as colonial subjects. Without the willing collaboration of large parts of the population, colonialism would have been impossible.”

With respect to the motives and the legacy of German colonialism, Gilley makes the argument that it was not primarily a plundering undertaking, in which blacks were to be treated as sub-humans and whites could treat them however they wanted—Gilley provides a number of examples of whites behaving badly in the German colonies and being punished for doing so. To frame it thus is not only to replace fact with fantasy but it is to ignore not only the statements of the colonizers themselves, but more important the voices of the colonized—Gilley provides numerous citations—who found that German colonial rule had bought greater peace and prosperity to them, thanks to placating tribal rivalries and long held animosities (Chapter 3 provides an analysis of the Herero and Nama peoples, and the imaginative claims that Herero-Nama wars were created by the Germans, or even more fantastically that they were gestures of anti-colonialism!). The major motivation, argues Gilley, is that colonialism was perceived as the accompanying condition of nation-building and being taken seriously as a major European power. The point is an interesting and important one, and it illustrates the vast gulf that separates the mindset of the generation that now dominates in the universities from that of a previous generation caught up in a completely different set of priorities of world-making.

Gilley provides numerous examples of what the German colonialists built, and again I will cite a few of his cases.

“Having first established peace in East Africa, the Germans proceeded to establish prosperity. A 1,250-kilometer railway was built linking Lake Tanganyika to Dar es Salaam. To this day, the railway remains the lifeblood of Tanzania’s economy and of Zambia’s trans-shipment traffic. The German colonial railway was not just economically beneficial. It also led to the documenting of the region’s geography, vegetation, minerals, and peoples—much of which was carried out by the German-English railway engineer Clement Gillman as he surveyed the new line.”

And,

“For the green conscious, it is especially noteworthy that German colonialism discovered the knowledge and crafted the regulations that protected the great forests and fauna of today’s Tanzania, Rwanda, and Burundi.”

And,

“Without doubt, Germany’s greatest humanitarian contribution to Africa during its colonial period was the discovery of a cure for sleeping sickness. In terms of lives saved, Germany’s colonial achievement could stand on this ground alone. Sleeping sickness originated in nomadic cattle-herding populations in Africa whose movements had spread the disease for hundreds of years before the colonial era. The increase in intensive farming under colonialism accelerated its spread, an inevitable result of policies to increase food supply and modernize agriculture. The disease was ravenous. The British calculated that an outbreak in 1901–07 killed between two hundred thousand and three hundred thousand people in British Uganda, and two million people succumbed in all of East Africa in 1903 alone.”

Nineteenth century colonialism is, as Gilley rightly notes, part of a genuinely civilizing approach to world-making. While that approach had both liberal and traditional European (conservative) accompaniments, it was also to be found in the communists Marx and Engels; and while the German socialists opposed how colonialism was being administered, they were, again as noted by Gilley, not unsupportive of colonial rule.

While the success of the modern, as these examples indicate, can be seen in terms of technical and technological advances, its diabolical underside is disclosed by the ideological concoctions that were to be transposed globally with far more devastating effects than colonialism itself. And if the first part of Gilley’s book might be an eyeopener for those who have not wanted to seriously think about what benefits accompanied colonialism, which is to say, those who have not thought out of the now fashionable moral academic box, the second part of the book makes the important point that both the Nazi and the communist projects were able to fuel anti-colonialist sentiments among various members of the aspirant elites in colonized country for their own geopolitical benefit and to the greater detriment of the societies in which these ideologically “educated” elites took power.

Need I say that any elite members wishing to gain power through national independence had no need to worry about the boring give-and-take and talk-fest that is endemic to democracies. Far easier to push through one’s will and that of one’s loyal support group or tribe and end up with—bloody chaos.

In an age where the holocaust is the diabolical terminus of history and anything and anyone from St. John to Luther to the family has been held up by some scholar or philosopher to be responsible, it is not surprising that colonialism would also be held responsible for the holocaust. But in spite of it now being commonplace among German academics to claim that there is line of continuity between German colonialism and the Nazis, the Nazis themselves from Hitler down wanted no truck with the colonialists and, in the main, few of the colonialists wanted what the Nazis wanted. In case anyone had not noticed, the Nazis were not in the civilizing business. Their fusion of nationalism and socialism, along with their antisemitism, and cult of the leader, was also embraced, along with open admiration for Hitler himself, by numerous anti-colonial leaders, most famously Nehru, Nasser, Amin and the Palestinian cleric Amin al-Husseini.

In the main, while academics don’t like the Nazis (unless they are Ukrainian ones who kill Russians and draw up hit lists of people to be liquidated for speaking out against them), they generally do like communists – in their upside-down world, communist rebels are freedom fighters. That communism is a Western ideological import that has not only exacerbated group and class conflicts but has been the means for justifying and entrenching “third world” elites with no idea how to better enhance economic conditions of people other than seizing land and property and pointing guns at people who must do what they are told.

The story of former colonies becoming entangled in the cross-fire of the Cold War like that of ambitious elites who used independence to secure their own power and wealth, along with those groups who give them their allegiances, is a horror story that belongs to the post-colonial age; but it is not the kind of story that neatly folds into a curricula or mind-set, where the answers to the cause of all things bad are white supremacism, i.e., European colonialists.

In a world as complicated as ours, the failure of the West to have an educated elite that are incapable of understanding the world before it, and the past behind it, is devastating. We are now living in that devastation; and although I detest those whose moral imaginations have been formed by sticking their heads in the bucket of Electric-Kool Aid Acid that now passes for an education, I have to concede that previous better-educated generations failed to see the consequences of their actions, and we are now living within those consequences.

Post script. Readers of a certain age will probably have recognised that I have borrowed the phrase “The Electric Kool-Aid” from Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Test, a book about Timothy Leary and his Merry Pranksters bussing across the US and their other shenanagins. This was in the days before college kids demanded safe spaces and fentanyl had become the drug of social breakdown. Wolfe was one of the founders of what was hailed as the new journalism in the early 1970s. Our world looks life the morning after what may have started as a party of sex and drugs and rock n roll and has turned into a nightmare of loneliness and totalitarianism.

Wayne Cristaudo is a philosopher, author, and educator, who has published over a dozen books. He also doubles up as a singer songwriter. His latest album can be found here.

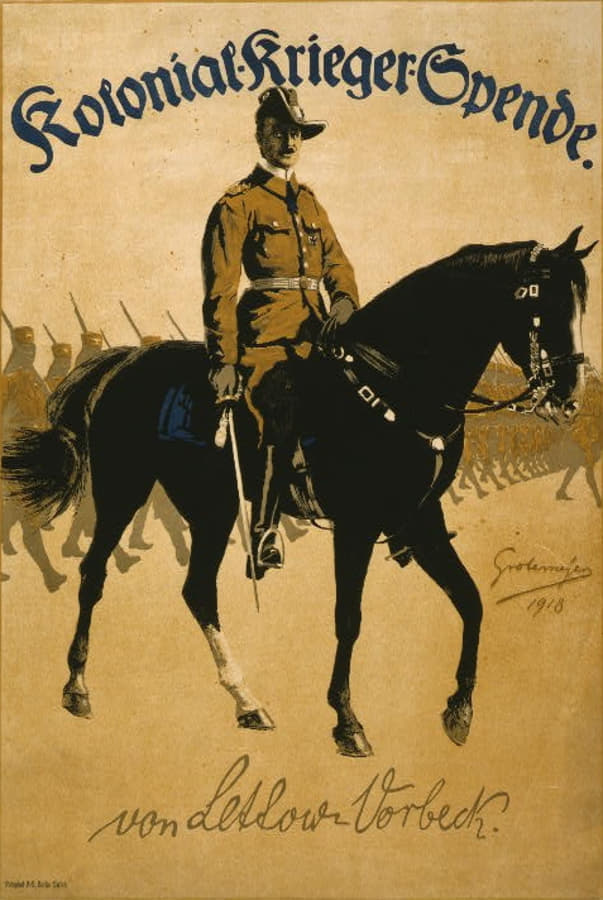

Featured: General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, the “Lion of Africa,” a poster by Grotemeyer, dated 1918. The caption reads: “Kolonial-Krieger-Spende,” or “Colonial Soldiers Fund.” Signature of von Lettow-Vorbeck at the bottom.