We are so very pleased to offer to our readers a first look at Bruce Gilley’s latest book, The Last Imperialist. Sir Alan Burns’ Epic Defense of the British Empire. This excerpt is made possible by the kind generosity of Regnery Publishing. Please support this important research and purchase a copy – and tell others.

Bruce Gilley is a Professor of Political Science at Portland State University. His research centers on the empire, democracy, legitimacy, global politics, as well as the comparative politics of China and Asia.

By the 1930s, most colonial governments were under pressure to set out a plan for self-government if not outright independence. India was the furthest along, and African, Asian, and Caribbean nationalists wanted to follow. Good government was losing its appeal amid the allure of selfgovernment. British socialists and communists, including Alan’s brother Emile, were calling for the empire to be handed over to the League of Nations. The Belize Independent columnist and Battlefield general Luke Kemp told his readers that they should follow the advice of Emile, “reputed to be the greatest exponent of the Marxist (communist) doctrine in England” and treat colonial rulers like his brother as temporary “aliens.” “It is the ‘great brains’ that ran this colony to the rocks. Now we ask that men we feel are honest be given a chance,” Kemp demanded. Universal suffrage was needed, because national unity would “be as strong as the political latitude granted to the entire population.” When colonial officials complained about the desultory singing of God Save the King on one occasion, Kemp riposted: “I am quite sure the English taxpayers and the Secretary of State for the colonies would be shocked at the result of a plebiscite in British Honduras as to whether a change to the Stars and Stripes would be desired.”

London had imposed direct rule on British Honduras after the 1931 hurricane to speed recovery. Alan returned the colony to partial self-rule in 1936 with the election of 5 of the 13 seats in the legislature. He gave women the vote for the first time. Even so, the number of votes cast in the 1936 election was a meager 1,300 (less than 5 percent of the adult population), compared to 1,900 in the election before direct rule. Many people had fallen below the income or property thresholds, while others simply could not be bothered to register or vote. Most of the votes, about 1,200, were cast for the two seats in Belize Town. Of the other three seats, two were acclaimed. One returned a candidate whose nomination papers had been signed by a road crew. Robert Turton, the chewing gum nationalist, won the northern chicle district by sixty-five votes to forty-four. Given Alan’s legislative experience in the Bahamas and his “great ability as a speaker,” the Belize Independent bemoaned, the government bloc in the legislature—consisting of six officials and two appointees—was “so well clothed with power that their position” was “nigh impregnable.” Alan was “a Mussolini” for the way he “swept aside” opposing views in legislative sessions.

As in the Bahamas, London argued that any attempt to loosen voting qualifications would cause a backlash from white elites fearing mob rule. Luke Kemp, for instance, wanted only blacks and Creoles to be given the vote under his “natives first” plan. The Maya would be relegated to a secondary

role while whites would be disenfranchised or even expelled. Kemp wrote that “fascism or Nazism is a superior form of government” to colonial rule “for food, shelter, and medical treatment are within the reach of citizens and it is only the small minority that suffers unjustly.” Soberanis and Kemp

appealed for “closer association” with military-ruled Guatemala despite its comparative poverty and instability. Law and order “would be so under any flag,” Kemp wrote. Just as Haiti provided a sobering reminder to citizens of the Bahamas of the dangers of popular government, Guatemala, which had thrown off the colonial “yoke” in 1821 and similarly descended into a century of chaos, did

so for British Honduras. When Alan arrived, the conditions of the working class in Guatemala were far worse than in British Honduras, and labor leaders there were simply killed by the government. For the colony’s middle classes, a populist politics that led to control by Guatemala or by a native fascist regime would spell disaster. When Guatemala mobilized troops on the border in 1938, even the Belize Independent scurried for cover: “British Honduras must ever remain a British colony.”

For Alan, demands for political advance were rooted in demands for social dignity. “The one problem at the bottom of all their troubles, and the ones for which they passionately seek a solution, is how they are to obtain from the white world that recognition of social and political equality which has, up to now, been denied them,” he would write. When the German boxer Max Schmeling defeated the black American boxer Joe Louis in the first of their two fights in 1936, Alan recalled, “The gloom among the coloured inhabitants of British Honduras was worthy of a major national disaster.” Colonialism had, for better or worse, brought “social restrictions and personal insults” to subject peoples which prevented them “from recognizing or admitting” its great benefits. “The inevitable effect of this is that the unthinking mob . . . will follow the noisy and irresponsible persons who freely express their hatred of the white man and promise the people fantastic and impossible things.” The task was to expand democracy without handing over power to demagogues. Holding ultimate power in the hands of the governor for as long as possible, Alan would later write, was critical because it “ensured that British humanitarian and liberal principles should prevail, for the benefit of the underprivileged and often illiterate classes, against the selfish policies of the members of the old Assemblies.”

Alan drove this lesson home in his reform of the Belize Town Board. Since its founding in 1912, the board had been treated as the de facto democratic legislature of the colony because of its elected majority (eight out of fourteen seats). Board members typically debated issues far outside their purview, and the board was diligently covered in the local press. But it was also dysfunctional,

constantly in turmoil over committee battles and mutual recriminations. It failed to collect most of its taxes and most of its elected members were in arrears on their own taxes. One local merchant called it “effete, dishonest, and a menace to the progress of our City.” Without consultation or explanation, Alan cut it down to five elected and five appointed members for the 1936 election.

The act by Il Duce caused outrage on the Battlefield. But locals noticed that municipal affairs were working better and that day-laborers on town projects were being paid on time. A new “Sanitary Brigade” kitted in khaki replaced the slovenly food market and street inspectors of the defunct board. In 1938, Alan suspended the board altogether pending a reorganization. He made himself chairman of an interim board and was seen on the streets inspecting clogged drains and filthy latrines. Kemp eventually admitted that “90 percent of the citizens of Belize wanted the defunct board to be abolished” and congratulated Alan on “a master step.” Alan had proven his point: when faced with a choice between good government and elected government, colonial peoples would prefer the former. Clean latrines and operable sewers might not stir the passions on the Battlefield, but they made lives better and laid the foundations for durable democracy.

True to his word, Alan restored the democratic nature of the Belize Town Board in 1939 with six elected and three nominated members. All nine were non-European, marking the first all-local and majority-elected council in the colony’s history.101 He also added one elected member to the colonial legislature in the 1939 election, replacing a nominated member, leaving the government bloc with a slim majority of just seven to six. In these ways, Alan was balancing his liberal instincts with his attention to administrative efficiency. “It is not logical,” he would write, to tell colonial subjects that “all men are equal before the law and then to deny him the equality which he claims.” Democracy was clearly desirable. On the other hand, if that “right” came at the cost of death and destruction, it would be a poor trade. Like his growing interest in racial questions, his political reforms in British Honduras presaged a growing interest in the question of when and how a colony could be brought to independence. He rejected the idea that “independence should be given forthwith to those colonials who ask for it, whatever may be their competence to govern themselves, and regardless of the consequences to the mass of the population.” There would be nothing noble about decolonization if it caused countries to implode. “It would probably save us a lot of trouble and win us the applause of the unthinking if we surrendered at once to all the demands for self-government and rid ourselves of the burden of trusteeship,” he would later comment. “But we have a duty to the people of the dependent territories and to the world at large that it would be cowardly to shirk, and we could not later escape the responsibility and the blame for the disasters that would follow if we abandoned our trust.”

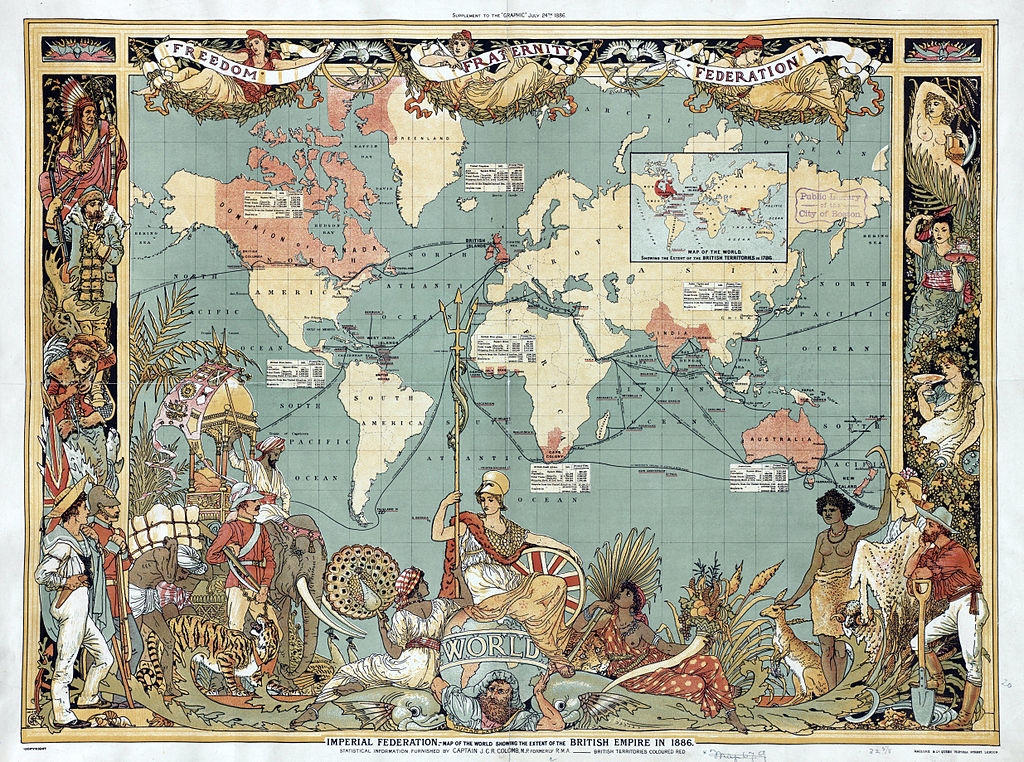

The featured image shows the map of the British Empire by Walter Crane, printed in 1886.