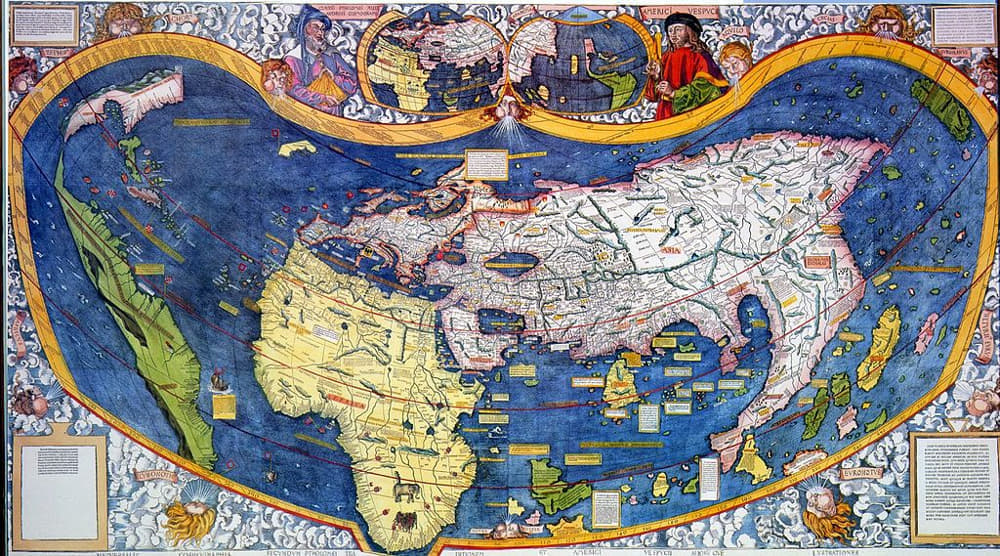

The relationship between Russia, Turkey (and the impact of it on Europe) is very long and controversial issue, marked by persistent hostility and with eleven wars (including WWI). The first war started in 1568, when Russia was still in the initial phase of her statehood path.

It is remarkable that the only occasion where Russia (in Bolshevik format) supported Turkey, was when Ankara faced Western Allied pressure and the Greek invasion after WWI, as retaliation for the Allied support of the ‘White’ counter revolutionary forces.

This situation, a de facto alliance against a mutual enemy, should be remembered as a thin red line which remains pertinent right up to today.

This complex and problematic cooperation-confrontation, especially during the 18th century, impacted several times the wider problem of stability of Europe, the Mediterranean and the Levant, and it is re-proposed today, in terms which adapted themselves to different situations and contexts.

Limiting the analysis to recent times, despite many (old and new, and growing) divergences, Moscow and Ankara have in common the use of foreign and security policies as a projection tool to limit the impact of domestic problems through external successes and to consolidate the internal cohesion, eroded by different factors.

Turkey’s aggressive policies in recent years, which raised great concern among its NATO and EU allies and partners, gave an important window of opportunity to Moscow to benefit from Ankara’s new assertive stance, perceived as a way to disrupt the internal cohesion of the Euro-Atlantic economic and security architectures.

Aware of the fundamental differences with Turkey (and the related management problems), Putin seeks to keep the relationship as fruitful as possible for the interests of Moscow.

Russia and Turkey were able to arrive at a quasi-positive understanding, pragmatic and case-by-case in areas of conflict, where both often support opposing sides, as in Syria, the Black Sea, Libya, the Caucasus, Sahel and elsewhere.

The (not full) cooperative confrontation model between Moscow and Ankara has been successfully implemented in different geostrategic theatres without the need for formal agreements.

The Decreasing Of The Economic Dimension

To better understand the dynamics of the Russian-Turkish relations and its contradictions, the economic dimension remains pivotal, even if it is not particularly strong, and appears altogether in decline.

Russian exports to Turkey in 2019 were around $17.75 billion and its imports around $3.45 billion. An increase of 2.5%, compared to 2018, and lower than the $31 billion reached in 2014, before the crisis of 2015, when a Russian plane was downed over Syrian airspace by Turkish jets.

Aside from that, Turkey gradually reduced its dependence on Russian gas, firstly because of the slowdown of the domestic economy, and the development of liquefied gas infrastructure as alternatives. Gazprom supplied up to 52% of Turkish gas imports, even planning to expand supply by building the “TurkStream” pipeline. This supply fell to 33% in 2019, in favour of Azerbaijan, which became the main supplier to Ankara.

Moreover, the promising gas exploration results in the Black Sea could make it possible to reduce Ankara’s dependence on Russian gas, even if the hopes for that are old and recurrent; this plan would require time to be verified and, if confirmed, require more time to become functional. Further, the activation of the “North Stream II” pipeline will reduce any urgency to complete the “South Stream” one and, as a consequence, any leverage for Ankara.

Despite the decrease of the hydrocarbons sector, energy remains relevant because of the ongoing important project – the construction of the nuclear power plant of Akkuyu by the Russian company Rosatom, which is planned to be completed by 2023, at a cost of 20 billion dollars. (It is very rare that Russia shares civil nuclear technology with third countries; only with Algeria is there a similar plan, but which is still at the initial, negotiation phase).

The interests of the two states – are increasingly divergent, and the role of energy is demonstrated by Iranian oil. While Moscow is trying to prevent flooding the world market, as it would result in a drop in oil prices, thus drastically reducing its own revenues – Ankara instead is keen on Iranian oil and gas to come to the world market through its territory, which would reinforce Turkey’s ambitions of becoming an energy distributor and hub.

Tourism, however, continues to record important growth with more than 7 million Russian tourists visiting Turkey each year, making Russia one of the largest visitors to the Mediterranean country before COVID-19.

The Security And Military Dimension

Moscow looks to preserve the recently built relationship by de-escalating the crises that have arisen with Turkey, despite the problems with Ankara; and the disruptive approach of Erdoğan towards the West is very useful to Russian strategic interests.

An example of this stance was evident when Turkey shot down a Russian Su-24 strike bomber in Syria in November 2015, and relations became very tense (even close to rupturing). But Moscow carefully managed its retaliation, avoiding extreme measures that might affect the growing ties between the two nations.

Given that Turkey is a NATO member, Russia is obliged to consider also the possibility that in case of a major crisis with the Alliance, Turkey could close the Bosporus Straits with the support of its Western allies and regardless of the spirit and the letter of the Montreux Convention of 1936.

This scenario for Moscow would be almost a “nightmare” because it would risk interrupting the pivotal line of communication between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean (and, via the Suez Canal, to the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean, and from Gibraltar to the Atlantic Ocean).

As mentioned earlier, Moscow tries to exploit as much as possible the various disputes that have antagonized Turkey with other stakeholders (France, Greece, Cyprus, Israel, Italy, UAE, Egypt), thus undermining the system of Western alliance, especially in the matter of delimiting the EEZ and exploitation of hydrocarbons reservoirs.

In this light, the series of disputes between Turkey on the one hand and Greece and France on the other side, in the Eastern Mediterranean and Libya, open opportunities for Russia to exploit and weaken Atlantic Alliance solidarity. The recent example of this is the special bilateral agreement, just signed, between Athens and Paris for security and defence aside/inside/outside NATO and EU frameworks is, in the final analysis, a weakening of Western security cohesion and an advantage for Moscow’s plans.

Thus, for Moscow, the military aspect of the mutual relationship, with Turkey’s NATO membership, is undoubtedly the most important component to consider in geostrategic planning.

In light of this, Putin supported Erdoğan fully after the attempted coup in July 2016 and offered for purchase to Turkey the S-400 “Triumph” anti-aircraft missile system; and thus also worsening the cohesion of the Atlantic Alliance, jeopardizing the integration of its air defence and C3 system.

For the EU pillar, the situation is similar. Even if Turkey’s relationship with Brussels is seriously to deteriorate because of the Cyprus situation, civil rights issues, the Libyan and Syrian files, or the use of migration as a tool of pressure, there is a possibility of a potential improvement.

But due to the weakness of EU facing the Ankara’s blackmail and the incapacity of Bruxelles (and its Member States) to face it with a firmer and at the same time more cooperative stand, there is a further indirect advantage of the strategic planning of Russia to undermine the Western economic and security architectures.

Two Cold Friends

The two leaders have not developed any personal affinity, revealing that both are aware of each other’s projects, views and perceptions and the similar, undemocratic nature of the two countries.

This, even weak, friendship is not, and likely will not be, the basis for ideological rapprochement, and also if the two countries are marked by an authoritarian approach; while this ‘brotherhood’ is more profound and evident between Russia and China, probably due to the previous Communist ideological base.

The major ideological element of distrust for Moscow is the Erdoğan’s vicinity (and in many cases with real support, like in Syria and Libya) to the galaxy of Muslim Brotherhood groups. These groups are banned in Russia and Moscow closely monitors their activities, especially in Muslim-populated areas of the Caucasus and Central Asia; and Putin is fully aware of the Turkish leader’s ambitions to lead the Muslim world.

Despite the suspicions, Moscow seeks to work with Ankara to control and moderate the extremism of Muslim populations. Also, here there are inconsistencies; Turkey continues to express support of the Tatar Muslim minorities in Crimea (the Ukrainian region unilaterally annexed by Russia in 2014), but avoids irritating Russia, and without any real action.

As mentioned, Putin is fully aware of the threat posed by jihadist extremism in the domestic dimension. So, the fact that the Turkish leader has ambitions to lead the Muslim world is a real concern for the Kremlin, which is constantly claiming at all occasions to cooperate with all the international community to fight against Islamic terrorism alongside Europe.

If Russian and Turkish interests would expand other geographical areas, the risk of mutual confrontation would increase; but also as problems that might be created in one area could be solved by resorting to a quid pro quo in other regions with the implementation of the pragmatic approach of Moscow and Ankara.

Mutual Influence?

In any bilateral relation, the influence that one partner may exert over the other, is a fundamental parameter to analyse.

It appears that Russia has more leverage with Turkey than the contrary. This asymmetrical situation emerged after a Russian plane was shot down in Syria in 2015 by Turkish jests.

Since then, Russia, while avoiding cornering Turkey in an untenable situation, increased the pressures on Ankara, from restrictions on trade and movement of people between the two countries, to the threat of canceling the nuclear energy power station project and launching media and social media campaigns targeting Erdoğan and his family’s alleged businesses in Syria, using well-organized resources, inherited from the Cold War.

Further, Moscow has in hand an old, but still powerful, and destabilizing asset against Turkey – the support for Kurdistan independence; especially with the assistance to PKK (Kurdish Worker’s Party, which has existed since the days of the former USSR and the Cold War era), and which is a serious problem and a constant source of irritation for Ankara. Also, even if in a more covert way, Russia supports the Kurdish forces operating in Syria and Iraq, and this is another reason of concern for Turkey, which saw any Kurdish presence, a threat to its national security. (In fact, Ankara has pressured Washington to cut support to the Syrian and Iraqi Kurds regardless if they fought against ISIS/Al-Qaeda elements, but without significant results).

However, Ankara also believes that it has several assets of influence, such as, Russians (mainly from Tatarstan) studying in Turkish universities, the Northern Caucasus diaspora living in Turkey, or the millions of Russians who as tourists enjoy Turkish beaches every year and are to some extent attracted by its culture. Ankara is convinced that the Russian intervention in Syria would prevent the consolidation of Kurdish autonomy in the region (the Bashar Al-Asssad government, despite using Kurdish forces to fight against the Islamist insurgents, is strongly against the establishment of any idea of setting up of an autonomous Kurdish region within Syria; this is welcomed also by the Syrian neighbours, other than Turkey, because it would pave the way for a future Kurdish state which may include the autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan, the Iranian Kurdistan, and the largest part of this possible entity, Kurdish Turkey).

Case Study Of Cooperation And/Or Confrontation: Syria

Syria is the main area where there is the highest risk of collision between Turkey and Russia; but at the same time, it is the area, where the two powers, despite their polarization and divergent interests, have established, even if unstable, a cooperative model.

Russian intervention, since September 2015, prevented the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s government, which was (and still is) Turkey’s long-term objective. It should be remembered that the controlling or weakening of Syria, under the French mandate after independence since 1945, has been a strategic target of Turkey, after the establishment of the republic in 1923.

It was thus surprising that in 2016 Putin brought Erdoğan into a trilateral meeting with Iran (the so-called “Astana,” the Kazakhstan capital city, dialogue format), which has however not been possible since February 2019, although this forum remains active at various levels, where it is able to design small-scale solutions.

Erdoğan, it should be remembered, initially was openly supportive of the Islamist insurgents and, for a period, openly sided with them and was strong allied with the Gulf States in support for the ISIS/Al Qaeda project to dismantle Syria (and Iraq), destroy the Sykes-Picot accord scheme, and set up a radical Islamist state, until its possible absorption by Saudi Arabia, according to informed reports.

Riyad had, and appears to have till today, the dream to re-purpose itself as the “new” (old) Hashemite project, in the Saudi hands, to re-unite all the Mashrak Arabs and territories into a united kingdom.

According to some analysts, when Erdoğan became aware of this plan, which collided with his own hegemonic project to re-establish the Ottoman domain over the Arabic peninsula, he broke with Riyad and approached the new deadly enemy of the Saudis – Qatar, which has become close to Iran, the strongest opponent of Riyadh.

The fact is that the Astana meeting of 2016 laid the groundwork for a compromise in October 2019 on “zones of controls,” which, although it did not satisfy any of the attendants, remains in place despite the violations.

When Turkey significantly increased its involvement in the Syrian conflict, the Assad government had no choice but to adhere more than ever to Russia, while Iran did not have the capacity to counter Turkey entering in the structure established by Moscow.

Thus, Turkish involvement allowed Moscow to dominate the Syrian scheme, albeit indirectly, reducing Iranian influence and limiting Ankara as well, right to the border area with Turkey.

In turn, other regional actors such as Saudi Arabia gradually reduced their impact on the Levant, as did Western diplomacy, making Ankara the dominant power supporting some of the Syrian opposition forces.

In this way, by controlling the warring factions in Syria (like Islamist “moderates,” ethnic Turkish militias), Moscow, and Ankara are now, even if on opposite sides, the masters of conflict (which has been case, tragically, since 2011).

The “Astana” format meeting in 2016 also contributed to moving the focus of international mediation mechanisms—put in place in both Vienna and Geneva—thus helping to increase their control of the conflict. Over time, the understanding between the two powers has contributed to diminishing Tehran’s influence, as tensions between rebels, Turkish proxies and Assad’s forces are better resolved through dialogue between Moscow and Ankara than through the trilateral Astana format.

Examples of this Russian-Turkish understanding or “cooperative hostility” can be found in 2016, when Russia gave the green light to Turkey’s operations in Syria, receiving in return the green light for Damascus’s forces to takeover Aleppo, the most important city under rebel control, in a clear quid pro quo.

The volatile situation in Syria may change, while Russia seems firm in remaining there, especially now that Damascus has overcome the worst crisis. The US could decide to change again its strategy there, which would change further the scene of the current situation and impact the Turkish stance and its relations with Moscow.

The Other Area Of Confrontation And/Or Cooperation: North Africa

North Africa appears to be the best area where the two divergent approaches of Russia and Turkey find now the best example.

The first example is Libya. At the end of 2019, Turkey decided to increase its involvement in Libya by sending military advisors, Syrian mercenaries and drones units belonging to the country’s regular armed forces in support of the UN and EU-(formally) backed government, based in Tripoli, which had the support of several Islamist militias. On the opposite side are Marshal Haftar’s forces, supported by the UAE, Egypt, Russia, and France.

Again, we could see how the intervention of one of the stakeholders in support of one faction enhances the importance of the other stakeholder’s help for the other side.

The intensity of Turkish support stopped Haftar’s offensive in its tracks, forcing him to seek further support from Moscow, which reacted by sending “Wagner” private security firm contractors and modern weapons systems (including MIG-29 fighters “Fulcrum” and Su-24 bombers “Fencer” and SAM units) along with personnel to operate and train the local staff.

The result produced a stalemate in the conflict, in which Turkey and Russia have once again contributed to be the most influential players in a conflict in a third country, and also favoured by US passivity and intra-European split (especially the France and Italy polarization in supporting the two powers there; Rome, openly, the Tripoli-government, and Paris, with a more discrete and ambiguous approach, the one in the East).

The present stalemate would end with the planned Libyan elections, planned for the end of the current year or the beginning of 2022. Regardless, the timing the elections and the formation of a nationwide government in Libya which will follow, will re-open the terms of the relations of Moscow and Ankara, at least in that region.

Russia, like Turkey, appears firmly oriented to (re)-establish a base on Libyan territory, expanding slowly but firmly, its footprint in the Mediterranean basin (it already has bases in Tartus and Latakia, Syria), and its target is to have a naval base in Benghazi and/or an air base in Tobruk. If this is achieved, this plan would substantially strengthen Moscow’s position in the central Mediterranean, and consolidating the Eastern one, and paving the way for the Western one.

Algeria is the most recent sub-area of the Mediterranean basin where the two cooperate.

Since independence, achieved in 1962, Algeria is a pivot of the great strategy of Moscow to get influence in the Mediterranean region; and during the Cold War, the use of the harbour of Oran Mers El Khebir was a real threat to the NATO naval forces in the Western and Central Mediterranean. After the collapse of the USSR, despite the end of the presence in Oran, Moscow was able to keep strong ties with Algeria, especially with the selling of more and more sophisticated weapons systems; Algeria, to face the hostility of Morocco, fully pro-Western, also maintained good relations with Moscow.

Now, with the persistent crisis in Libya, and to re-propose the Ottoman dream (when Algeria had a semi-autonomous status led by a “dey” under the nominal suzerainty of the Sultan of Constantinople), but also in more prosaic terms, to make its presence in Tripoli more efficient, Ankara boosted her penetration policy in Algeria.

The Algerian leadership, which crushed with an iron fist a bloody Islamist insurgency in the 1990s, looks with a mixed feeling at Turkish diplomatic action, given the sympathies Ankara has for political Islam. But the need of stabilization in Libya requires collective action, and Ankara may represent a partner, even with limits (Algiers refused the Turkish request to host air units, tasked to operate in Libya, in its soil and did not allow the use of national airspace to Turkish jets).

The recent worsening of the French-Algerian relations, due to words of President Macron (and other older issues), could be considered a window of opportunity, where both Russia and Turkey, with different channels and impact, take the chance to consolidate their contacts (already very solid for Moscow) with Algiers in antagonizing France and reducing the room of influence of Paris in its former colony.

Again, the pragmatic approach of their relations, shows that Moscow and Ankara have found a modus vivendi, semi-acceptable, making it altogether tenable.

For Russia, the decline of French (and Western) influence in Algeria is a main target, given the weight and role of the North African country in Africa, the Arab world, Europe and the Mediterranean; and Moscow makes clear that it is looking for more naval bases around the world, and Algeria was specifically mentioned in a speech by the Minister of Defence, Serghei Shoigu.

A Sensitive Area

Meanwhile, the same model of cooperative, mutually beneficial confrontation between Russia and Turkey saw a recent revival of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia and the tensions that followed.

The long-standing open failure of the Minsk Group of OSCE (Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe) to establish a negotiated framework for the Nagorno-Karabakh region, pending since 1991, was the open excuse for Azerbaijan to launch its latest successful offensive, recapturing a large part of the region, and inflicting a heavy military defeat on Armenian forces. Baku was strongly supported by Turkey with military advisors and state-of-the-art equipment in terms of drones (including the suicide-like versions of those), communications systems and sensors. After that, Turkey saw an important rise of influence in Baku’s policies.

These successes reinforced Turkey’s ties with Azerbaijan, to the point of launching the idea of “two countries, one people” (re-proposed on a small scale, the dream of “Pan-Turanism” as a project of uniting the Turkish ethnic people from the Mediterranean to Asia, which is also the third element of the ideological architecture of the Erdoganism project, together the rebuilding of the Ottoman Empire and the defence of islam). Thus, Erdoğan visited his Azerbaijani counterpart Ilham Aliev last December to celebrate the joined victory against the Christian and Westernized Armenia.

Both Turkey and Russia have thus consolidated their influence in the region. Turkey, which through Azerbaijan looks to gain access to the Caspian Sea and tries to assert itself in a region where its cultural, ethnic, and linguistic ancestry gives it influence.

It should be added, after the conflict, Ankara has tried to deploy military observers in the area; Russian opposition prevented it, despite the previous agreement, and limited the presence of Turkish military to the nominally bi-national, peacekeeping force, of some staff officers at the mission HQ.

Although it may seem contradictory, Russia also benefitted from the conflict by supporting defeated Armenia. In fact, since 2018, Armenian PM Nikol Pashinyan has been convinced by US and France (countries where there is a large, influential, and rich Armenian diaspora) to pursue a pro-Western agenda, to the detriment of Russian interests and historical ties. But, after the successful Azeri operation, Armenia was abandoned (as usual) by Western powers – forcing Erevan to turn to its traditional ally and security guarantor, Russia, which provided an additional security guarantee to Armenia in case of possible military pressure from Turkey in support of Azerbaijan. (A similar controversial personality like Mikheil Saakashvili in Georgia had the same fate, initially supported by the West, then abandoned as corrupt and thus undesirable).

Russia, for its part, is consolidating its position as the dominant power over weakened Armenia—taking advantage of the West’s fickleness—as the guarantor of the peace agreement. Further, the use of the Caspian Sea (and the Eastern Mediterranean sea) as launching range for the spectacular firing of pre-strategic cruise missiles Kalibr/ Biryuza, hitting Islamist insurgent targets in Syria, rang an alarm bell for many stakeholders, in the region, and outside.

Moscow, for the time being, has reinforced its “buffer zone” in the Southern buffer despite pressure from NATO and has increased the pressure against the pro-Western Georgia.

The New Frontier Of Cooperation And/Or Confrontation Between Moscow And Ankara: Sub-Saharan Africa (Another Fissure Of Western Influence)

The recent Turkish presidental tour in Angola, Nigeria and Togo coincided with the announcement of the end of Sahel’s French operation “Barkhane,” and he seems determined to invest in African military terrain, and continue his offensive against France and the West everywhere.

Determined to accelerate his country’s diplomatic and economic offensive in Africa, since the option of rapprochement with EU faded at the turn of the 2000s, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is investing more and more in the sub-Saharan Africa.

Turkey already has significant economic weight in West Africa, which has enabled it to obtain from several governments in the sub-region the closure of schools close to the Gülen Islamist brotherhood (named after the imam Turkey accuses of having allegedly fomented the attempted coup d’état of July 2016), as was the case in 2017 in Senegal. On the security front, however, this cooperation is still in its early stages. Turkey, which has been hosting Malian officers for training since 2018, has donated $5 million to the G5 Sahel force and signed a military agreement with Niger in 2020.

It seems that Erdogan is seeking to fill the gaps left by the partial withdrawal of France. This option may collide with at least with one of the hotspots of the new politico-diplomatic-military offensive of Russia in the so-called “FranceAfrique” – Mali (the other, as of now is the Central African Republic).

In Mali, Moscow seems to have made an intensive bet, in providing military assistance (again the “Wagner” contractors, but only initially; and now also with provision of military hardware) and getting advantage with the growing hostility of the local population for any Western presence (e.g., the EU Training Mission, the UN Mission [MINUSMA]; the multinational European special force, Takuba, the presence of the CIA’s drones and the support of previous corrupted leaderships).

For the time being, it seems too early to foresee any possible polarization between Moscow and Ankara in the sub-area. But the only certain element for any kind of analysis is that the two work against France (and indirectly NATO, EU, USA). The future will tell what comes of all this.

Conclusion

Although the Russian-Turkish cooperation model—essentially a model with a high military content—has shown its usefulness, turning war zones into frozen conflicts that benefit both actors, it might have its limits.

This situation could lead the endlessly erratic policy of Erdoğan to consider that aligning with his Western allies could provide him with more leverage in the conflict zones.

An evident sign of this appeasement attempt with Turkey is the communiqué of the NATO Summit in June 2021, where no mention was made of Russia’s expansion attempts in the Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa. The point was not to exacerbate Turkey, even though within the Alliance (and EU as well) there is a growing irritation against Ankara, with its blackmails, insults, and provocations.

This situation has led Moscow (according to its own logic) to instrumentalise as much as possible crises inside the Euro-Atlantic area with the aim of creating and/or widening rifts within the Western alliances and diversifying its focus.

Russian and Turkish dynamism are part of a new global geopolitical trend in which new emerging powers, such as Russia and Turkey, act in a coordinated manner to challenge Western interests.

In recent years the progression of the persistently ambiguous Russian-Turkish relationship, although not strategic, is bearing results for both the actors.

Regardless of reduced economic ties, ideological differences, Moscow and Ankara have reached, in pragmatical mode, a mutually acceptable mode of cooperation, despite supporting opposing factions in various geo-strategic theatres.

But, as mentioned before, the relation remains weak – especially for Erdoğan, because the Turkish leader has been compensating for growing domestic discontent with external military successes and interventions. And these successes are short-lived. He would be forced to embark on new and costly foreign adventures and further increase the already heavy pressure on the growing internal opposition, extremising the tensions especially with EU.

One of these potential external adventures, the most serious threat to the continuation of a stable relationship between Moscow and Ankara, could be the involvement of Turkey in the Ukrainian crisis, where it is providing support to the modernization of Kiev’s armed forces. Ukraine is a red line for Moscow and because of the nature of the two states, there is the risk of an uncontrollable escalation with an extremely worrying and uncertain outcome. Implementing such a scenario should be foreseen in advance because of the enormous risks it would entail, giving the limited possibilities of a rapprochement on security matters between the two states.

While the non-existence of a formal framework between Moscow and Ankara has allowed them to achieve significant results, this gap could represent a serious vacuum if the two enter into a collision route.

Enrico Magnani, PhD is a UN officer who specializes in military history, politico-military affairs, peacekeeping and stability operations. (The opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations).