Crisis situations are not conducive to the exercise of discernment. This is even more true in times of conflict, where this faculty is more necessary than ever. The very legitimate emotions that the horrors of war and the added effects of propaganda arouse polarize societies more than ever, and people’s intelligence is readily asked to “choose a side” which, whatever it may be, is rarely that of intelligence.

The Russian aggression in Ukraine is no exception to the rule, and remaining faithful to oneself is more than ever considered a betrayal, for all those—and there are many—who want to see us embrace their faith. Yet the dilemma is a big one for the true supporters of freedom.

Let us pass over quickly the easy and captious apology of Vladimir Putin. It is true that it was Poroshenko’s Ukraine, then Zelensky’s, which first did not respect the commitments made during the Minsk I and Minsk II agreements on the relative autonomy of the country’s eastern and Russian-speaking provinces. It is true that NATO has played a perverse and destabilizing role by implicitly promising Ukraine membership without ever explicitly offering it. It is true that the Western democracies in general and the European Union in particular have behaved in an unavowable way like so many crime-pushers by arousing—or even creating from scratch—an anti-Russian resentment which is not far from constituting today the essential part of the Ukrainian identity; an identity which would have been very difficult to discern from the Russian identity even forty years ago.

An Indignation with Variable Geometry

The fact remains that peoples are supposedly free to decide their own destiny—especially when they subordinate it to the prior implementation of democratic mechanisms—and that the Ukrainians had the right, like so many others before them, to decide their future as an independent nation. In this light, however, the undignified treatment that the Kiev regime has imposed on its Russian-speaking citizens since 2014 is all the more regrettable because it did not fall within the scope of these famous democratic mechanisms and was the surest route to the Russian intervention that Kiev was precisely trying to get rid of.

But this is not the question I want to raise. As many feel, what is at stake is not so much Ukraine’s freedom as our own, which is being eroded more and more each day. If Ukraine was not just a pretext to weaken Russia, why this silence on Armenia? Why this silence on the Kurds? Why this silence on Yemen? Why this silence on so many other vales of tears where the serenity of the criminals feeds on the indifference—not of the Westerners—but of those who manufacture their opinion. The question then immediately arises: Why then would our immense media arsenal conspire day and night, as it does, to over-abundantly establish the crimes of Vladimir Putin, and not those of Ilham Aliev, and not those of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan; and not those of Mohammed bin Salman?

Paradoxical as it may seem, the answer is that Putin and what he represents are the best guarantors of our freedoms. I insist—of our freedoms as Westerners, and not of course those of the Ukrainians. Of course, Putin is a bastard like the others. But—to use the well-known aphorism—the others are “our bastards.” What our powers reproach Putin for is not so much that he is a bastard as that he is not theirs.

A hasty or ill-intentioned reader might think that I am implying from these few truths that life would be sweeter under Russian rule. Certainly not, need I say it? But in a world where great totalitarian blocs confront each other, human freedom can only survive on the peripheries, on the margins, in those subduction zones that only their confrontation preserves from monolithic solidification. Everywhere else, free thought is withering away, whether under the merciless boot of Eastern tyrants or in the intellectual suffocation that Western democracies have become.

Freedom Needs a Multipolar World

A few prophets—from Georges Bernanos to Jacques Ellul, and from Pier Paolo Pasolini to Ivan Illich—have seen it with a prescience that makes one shudder: Served by an ever more intrusive technology, a society with the conformism of a termite mound forbids dissent a little more, every day. Where the good old totalitarianisms had to be satisfied with a façade of adhesion, postmodern totalitarianism has the means of its ambitions, that of monitoring, re-educating and domesticating the masses with an unheard-of finesse and depth. Those who claim that democracies guarantee pluralism where authoritarian systems impose the voice of the state are jokers: each uses its own methods—that’s all—and the “democratic” variety of the Western media is only the flexible and protean decorum of a domination that is not at all democratic.

In a recent and remarkable article, Gabriel Martinez-Gros affirms that “the war in Ukraine is characteristic of these resistances [against empires]. Russia is not the empire described here but a nation-state. The empire is us: the West.” The first proposition about the nation-state nature of Russia is certainly questionable. The second about the empire and its postmodern religion that we represent is much less so. For a long time, this empire may have seemed benign because of factors that fed each other: the existence of a threat in terms of a competing global ideological project—communism—and the relative moderation of the political practices of a liberal system that had to reckon with this competitor whose captious lures seduced and still seduce so many of our compatriots.

The disappearance of communism has led the liberal empire to throw off the now useless mask of democracy in order to impose its religious dogmas in an authoritarian manner—and with increasing brutality. If it is fashionable to denounce illiberal democracies, this should not hide the fact that we are now living in an anti-democratic liberalism: this integral liberalism—economic and societal, totally unbridled—does not bother to hide the cynical and unlimited greed that constitutes its psychological strength and sets about destroying with tenfold violence the nation-states and their institutions, which it rightly perceives as the last dykes capable of restricting its omnipotence.

The strategy of shock employed provokes a state of stupefaction within our societies which are its victims, just as a boxer who is knocked out standing upright no longer feels the new blows which are going to knock him down. One can no longer count the proven facts that—even ten years ago—would have brought the people out into the street and that today only provoke a fatalistic shrug of the shoulders: The evidence of Ursula Von der Leyen’s corruption? Shrug of the shoulders. The price of nuclear electricity indexed to that of fossil fuels? Shrug of the shoulders. The plundering in the name of the market of national companies such as EDF paid for with the taxes of the French? Shrug. The almost daily murder of French people by the occupation troops of “diversity?” Shrug. Our progressive but irremediable entry into a status of cobelligerent servants of the empire? Shrug. The extraterritoriality of American commercial law and consequently the legal exemption by which the United States pretends to exempt its citizens from the laws of the other countries where they reside? Shrug, etc., etc. This is why we must hope for the permanent maintenance and even strengthening of different poles of power throughout the world, even if there is nothing to distinguish them in their foundations. For—apart from the unlikely short-term hypothesis of their collapse—it is indeed from their imperial competition alone and in the no-man’s-land of their confrontations that free and liberated Man will still have a minimal chance of surviving in the future.

Laurent Leylekian is former director of the Euro-Armenian Federation for Justice and Democracy (Brussels) and former director of publication of France-Armenia magazine. He is now a political analyst, member of the Armenian Observatory and a regular contributor to the Huffington Post. This article appears through the courtesy of Revue Elements.

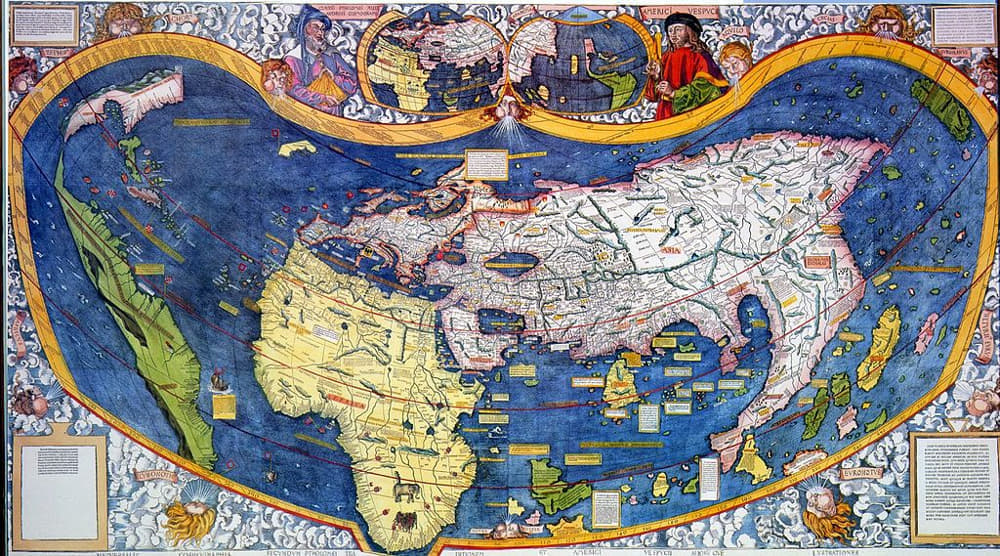

Featured: Martin Waldseemüller’s world map, ca. 1507-1508.