This story by Armando Palacio Valdés (1853—1938) was published in 1925.

He was born blind, and had been taught the one thing which the blind generally learn,—music; for this art he was specially gifted. His mother died when he was little more than a child, and his father, who was the first cornetist of a military band, followed her to the grave a few years later. He had a brother in America from whom he had never heard; still, through indirect sources he knew him to be well off, married, and the father of two fine children. To the day of his death the old musician, indignant at his son’s ingratitude, would not allow his name to be mentioned in his presence; but the blind boy’s affection for his brother remained unchanged. He could not forget that this elder brother had been the support of his childhood, the defence of his weakness against the other boys, and that he had always spoken to him with kindness. The recollection of Santiago’s voice as he entered his room in the morning, shouting, “Hey there, Juanito! get up, man; don’t sleep so!” rang in the blind boy’s ears with a more pleasing harmony than could ever be drawn from the keys of a piano or the strings of a violin. Was it probable that such a kind heart had grown cold? Juan could not believe it, and was always striving to justify him. At times the fault was with the mail, or it might be that his brother did not wish to write until he could send them a good deal of money; then again, he fancied that he meant to surprise them by presenting himself some fine day, laden with gold, in the modest entresol in which they lived. But he never dared communicate any of these fancies to his father; only when the old man, wrought to an unusual pitch of exasperation, bitterly apostrophized the absent one, he found the courage to say: “You must not despair, father. Santiago is good, and my heart tells me that we shall hear from him one of these days.”

The father died, however, without hearing from his son, between a priest, who exhorted him, and the blind boy, who clung convulsively to his hand, as if he meant to detain him in this world by main force. When the old man’s body was removed from the house, the boy seemed to have lost his reason, and in a frenzy of grief he struggled with the undertaker’s men. Then he was left alone. And what loneliness was his! No father, no mother, no relatives, no friends; he was even deprived of the sunlight, which is the friend of all created things. He was two whole days in his room pacing the floor like a caged wolf, without tasting food. The chamber-maid, assisted by a compassionate neighbor, succeeded in saving him from this slow process of suicide. He was prevailed upon to eat. He spent the rest of his life praying, and working at his music.

His father, shortly before his death, had obtained for him a position as organist in one of the churches of Madrid, with a salary of seventy cents a day. This was scarcely sufficient to meet the running expenses of a house, however modest; so within a fortnight Juan sold all that had constituted the furniture of his humble home, dismissed his servant, and took a room at a boarding-house, for which he paid forty cents a day; the remaining thirty cents covered all his other expenses. He lived thus for several months without leaving his room except to fulfil his obligations. His only walks were from the house to the church, and from the church back again. His grief weighed upon him so heavily that he never opened his lips. He spent the long hours of the day composing a grand requiem Mass for the repose of his father’s soul, depending upon the charity of the parish for its execution; and although it would be incorrect to say that he strained his five senses,—on account of his having but four,—it can at least be said that he threw all the energies of his body and soul into his work.

The ministerial crisis overtook him before his task was half finished. I do not remember who came into power, whether the Radicals, Conservatives, or Constitutionals; at any rate, there was some great change. The news reached Juan late, and to his sorrow. The new cabinet soon judged him, in his capacity as an organist, to be a dangerous citizen, and felt that from the heights of the choir, at vespers or in the solemnity of the Mass, with the swell and the roar from all the stops of the organ, he was evincing sentiments of opposition which were truly scandalous. The new ministers were ill disposed, as they declared in Congress through the lips of one of their authorized members, “to tolerate any form of imposition,” so they proceeded with praiseworthy energy to place Juan on the retired list, and to find him a substitute whose musical manœuvres might offer a better guarantee,—a man, in a word, who would prove more loyal to the institutions. On being officially informed of this, the blind one experienced no emotion beyond surprise. In the deep recesses of his heart he was pleased, as he was thus left more time in which to work at his Mass. The situation appeared to him in its real light only when his landlady, at the end of the month, came to him for money. He had none to give her, naturally, as his salary had been withdrawn; and he was compelled to pawn his father’s watch, after which he resumed his work with perfect serenity and without a thought of the future. But the landlady came again for money at the end of another month, and he once more pawned a jewel of the scant paternal legacy; this was a small diamond ring. In a few months there was nothing left to pawn. So the landlady, in consideration of his helplessness, kept him two or three days beyond the time and then turned him out, with the self-congratulatory feeling of having acted generously in not claiming his trunk and clothes, from which she might have realized the few cents that he still owed her.

He looked for another lodging, but was unable to rent a piano, which was a sore trial to him; evidently he could not finish his Mass. He knew a shopkeeper who owned a piano and who permitted him to make use of it. But Juan soon noticed that his visits grew more and more inopportune, so he left off going. Shortly, too, he was turned out of his new lodgings, only this time they kept his trunk. Then came a period of misery and anguish,—of that misery of which it is hard to conceive. We know that life has few joys for the homeless and the poor, but if in addition they be blind and alone, surely they have found the limit of human suffering. Juan was tossed about from lodging to lodging, lying in bed while his only shirt was being washed, wandering through the streets of Madrid with torn shoes, his trousers worn to a fringe about his feet, his hair long, and his beard unshaven. Some compassionate fellow-lodger obtained a position for him in a café, from which, however, he was soon turned out, for its frequenters did not relish his music. He never played popular dances or peteneras, no fandangos, not even an occasional polka. His fingers glided over the keys in dreamy ecstasies of Beethoven and Chopin, and the audience found some difficulty in keeping time with their spoons. So out he went again through the byways of the capital. Every now and then some charitable soul, accidentally brought in contact with his misery, assisted him indirectly, for Juan shuddered at the thought of begging. He took his meals in some tavern or other in the lowest quarter of Madrid, ate just enough to keep from starving, and for two cents he was allowed to sleep in a hovel between beggars and evil-doers. Once they stole his trousers while he was asleep, and left him a pair of cotton ones in their stead. This was in November.

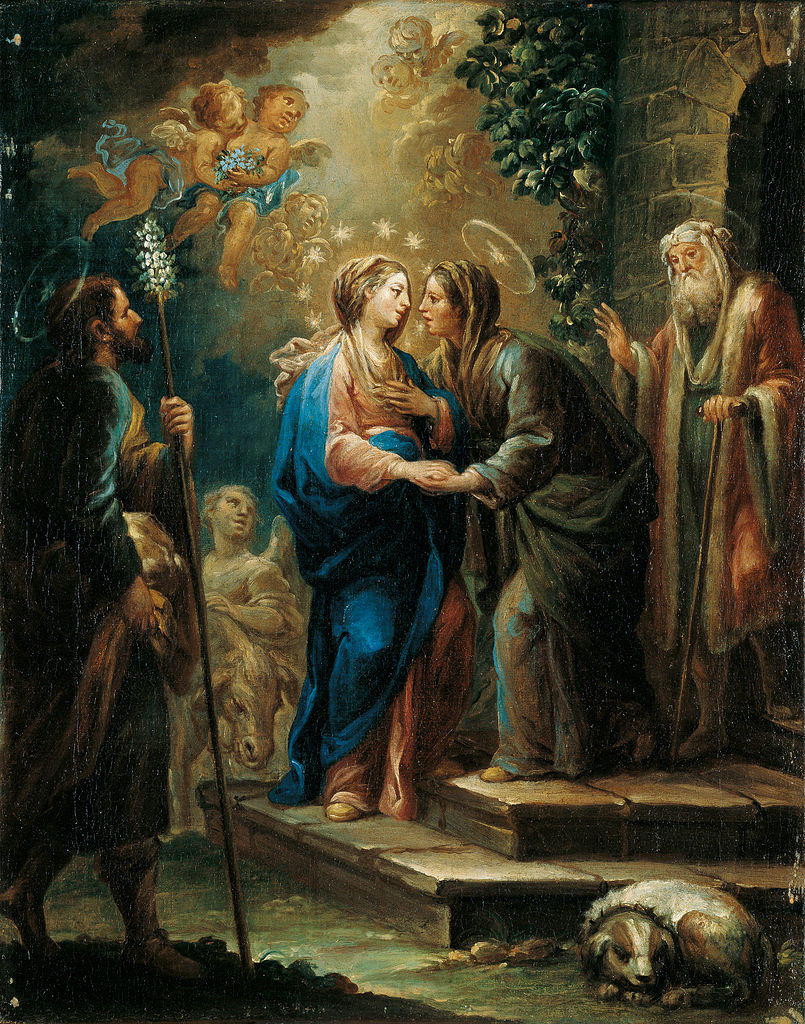

Poor Juan, who had always cherished the thought of his brother’s return, now in the depths of his misery nursed his chimera with redoubled faith. He had a letter written and sent to Havana. As he had no idea how his brother could be reached, the letter bore no direction. He made all manner of inquiries, but to no effect, and he spent long hours on his knees, hoping that Heaven might send Santiago to his rescue. His only happy moments were those spent in prayer, as he knelt behind a pillar in the far-off corner of some solitary church, breathing the acrid odors of dampness and melting wax, listening to the flickering sputter of the tapers and the faint murmur rising from the lips of the faithful in the nave of the temple. His innocent soul then soared above the cruelties of life and communed with God and the Holy Mother. From his early childhood devotion to the Virgin had been deeply rooted in his heart. As he had never known his mother, he instinctively turned to the mother of God for that tender and loving protection which only a woman can give a child. He had composed a number of hymns and canticles in her honor, and he never fell asleep without pressing his lips to the image of the Carmen, which he wore on his neck.

There came a day, however, when heaven and earth forsook him. Driven from his last shelter, without a crust to save him from starvation, or a cloak to protect him from the cold, he realized with terror that the time had come when he would have to beg. A great struggle took place in his soul. Shame and suffering made a desperate stand against necessity. The profound darkness which surrounded him increased the anguish of the strife; but hunger conquered in the end. He prayed for strength with sobs, and resigned himself to his fate. Still, wishing to disguise his humiliation, he determined to sing in the streets, at night only. His voice was good, and he had a rare knowledge of the art of singing. It occurred to him that he had no means of accompaniment. But he soon found another unfortunate, perhaps a trifle less wretched than himself, who lent him an old and broken guitar. He mended it as best he could, and with a voice hoarse with tears he went out into the street on a frosty December night. His heart beat violently; his knees trembled under him. When he tried to sing in one of the central thoroughfares, he found he could not utter a sound. Suffering and shame seemed to have tied a knot in his throat. He groped about until he had found a wall to lean against. There he stood for awhile, and when he felt a little calmer he began the tenor’s aria from the first act of “Favorita.” A blind singer who sang neither couplets nor popular songs soon excited some curiosity among the passers-by, and in a few minutes a crowd had gathered around him. There was a murmur of surprise and admiration at the art with which he overcame the difficulties of the composition, and many a copper was dropped in the hat that dangled from his arm. After this he sang the aria of the fourth act of “Africana.” But too many had stopped to listen, and the authorities began to fear that this might be a cause of disturbance; for it is a well-established fact with officials of the police force that people who congregate in the streets to hear a blind man sing are always prompted by motives of rebellion,—it means a peculiar hostility to the institutions; in a word, an attitude thoroughly incompatible with the peace of society and the security of the State. Accordingly, a policeman caught Juan energetically by the arm and said, “Here, here! go straight home now, and don’t let me catch you stopping at any more street corners.”

“I’m doing no harm!”

“You are blocking the thoroughfare. Come, move on, move on, if you don’t want to go to the lock-up.”

It is really encouraging to see how careful our authorities are in clearing the streets of blind singers; and I really believe, in spite of all that has been said to the contrary, that if they could keep them equally free from thieves and murderers, they would do so with pleasure. Juan went back to his hovel with a heavy heart, for he was by nature shrinking and timid, and was grieved at having disturbed the peace and given rise to the interference of the executive power. He had made twenty-seven cents. With this he bought something to eat on the following day, and paid rent for the little pile of straw on which he slept. The next night he went out again and sang a few more operatic arias; but the people again crowded around him, and once more a policeman felt himself called upon to interfere, shouting at him to move on. But how could he? If he kept moving on, he would not make a cent. He could not expect the people to follow him. Juan moved on, however, on and on, because he was timid, and the mere thought of infringing the laws, of disturbing even momentarily the peace of his native land, was worse than death to him. So his earnings rapidly decreased. The necessity of moving on, on the one hand, and the fact that his performances had lost the charm of novelty, which in Spain always commands its price, daily deprived him of a few coppers. With what he brought home at night he could scarcely buy enough food to keep him alive. The situation was desperate. The poor boy saw but one luminous point in the clouded horizon of his life, and that was his brother’s return to Madrid. Every night as he left his hovel with his guitar swinging from his shoulder he thought, “If Santiago should be in Madrid and hear me sing, he would know me by my voice.” And this hope, or rather this chimera, alone gave him the strength to endure life. However, there came again a day in which his anguish knew no limit. On the preceding night he had earned only six coppers. It had been so cold! This was Christmas Eve. When the morning dawned upon the world, it found Madrid wrapped in a sheet of snow six inches thick. It snowed steadily all day long, which was a matter of little consequence to the majority of people, and was even a cause of much rejoicing among æsthetes generally. Those poets in particular who enjoy what is called easy circumstances spent the greater part of the day watching the flakes through the plate-glass of their study windows, meditating upon and elaborating those graceful and ingenious similes that cause the audiences at the theatre to shout, “Bravo, bravo!” or those who read their verses to exclaim, “What a genius that young fellow is!”

Juan’s breakfast had been a crust of stale bread and a cup of watery coffee. He could not divert his hunger by contemplating the beauty of the snow,—in the first place, because he was blind, and in the second, because, even had he not been blind, he would have had some difficulty in seeing it through the patched and filthy panes of his hovel. He spent the day huddled in a corner on his straw mattress, evoking scenes of his childhood and caressing the sweet dream of his brother’s return. At nightfall he grew very faint, but necessity drove him into the streets to beg. His guitar was gone. He had sold it for sixty cents on a day of similar hardship. The snow fell with the same persistence. His legs trembled as they had when he sang for the first time, but now it was from hunger rather than shame. He groped about as best he could, with great lumps of mud above his ankles. The silence told him that there was scarcely a soul on the street. The carriages rolled noiselessly along, and he once came near being run over. In one of the central thoroughfares he began to sing the first thing that came to his lips. His voice was weak and hoarse. Nobody stopped to listen. “Let us try another street,” thought he; and he went down the Avenue of San Jerónimo, walking awkwardly in the snow, with a white coating on his shoulders and water squirting from his shoes. The cold had begun to penetrate into his very bones, and hunger gave him a violent pain. For a moment with the cold and the pain came a feeling of faintness which made him think that he was about to die, and lifting his spirit to the Virgin of the Carmen, his protectress, he exclaimed in his anguish, “Mother, have pity!” And after pronouncing these words he felt relieved and walked, or rather dragged himself, to the Plaza de las Cortes. There he grasped a lamp-post, and under the impression of the Virgin’s protection sang Gounod’s “Ave Maria.” Still nobody stopped to hear him. The people of Madrid were at the theatres, at the cafés, or at home, dancing their little ones on their knees in the glow of the hearth,—in the warmth of their love. The snow continued to fall steadily, copiously, with the evident purpose of furnishing a topic for the local column of the morning paper, where it would be described in a thousand delicate phrases. The occasional passers-by hurried along muffled up to their ears under their umbrellas. The lamp-posts had put on their white night-caps, from under which escaped thin rays of dismal light. The silence was broken only by the vague and distant rumble of carriages and by the light fall of the snowflakes, that sounded like the faint and continuous rustle of silk. The voice of Juan alone vibrated in the stillness of the night, imploring the mother of the unprotected; and his chant seemed a cry of anguish rather than a hymn of praise, a moan of sadness and resignation falling dreary and chill, like snow upon the heart.

And his cry for pity was in vain. In vain he repeated the sweet name of Mary, adjusting it to the modulations of every melody. Heaven and the Virgin were far away, it seemed, and could not hear him. The neighbors of the plaza were near at hand, but they did not choose to hear. Nobody came down to take him in from the cold; no window was thrown open to drop him a copper. The passers-by, pursued, as it were, by the fleet steps of pneumonia, scarcely dared stop. Juan’s voice at last died in his throat; he could sing no more. His legs trembled under him; his hands lost their sense of touch. He took a few steps, then sank on the sidewalk at the foot of the grating that surrounds the square. He sat with his elbows on his knees and buried his head in his hands. He felt vaguely that it was the last moment of his life, and he again prayed, imploring the divine pity.

At the end of a few minutes he was conscious of being shaken by the arm, and knew that a man was standing before him. He raised his head, and taking for granted it was the old story about moving on, inquired timidly,—

“Are you an officer?”

“No; I am no officer. What is the matter with you? Get up.”

“I don’t believe I can, sir.”

“Are you very cold?”

“Yes, sir; but it isn’t exactly that,—I haven’t had anything to eat to-day.”

“I will help you, then. Come; up with you.”

The man took Juan by both arms and stood him on his feet. He seemed very strong.

“Now lean on me, and let us see if we can find a cab.”

“But where are you going to take me?”

“Nowhere where you wouldn’t want to go. Are you afraid?”

“No; I feel in my heart that you will help me.”

“Come along, then. Let’s see how soon I can get you something hot to drink.”

“God will reward you for this, sir; the Virgin will reward you. I thought I was going to die there, against that grating.”

“Don’t talk about dying, man. The question now is to find a cab; if we can only move along fast enough—What is the matter? Are you stumbling?”

“Yes, sir. I think I struck a lamp-post. You see—as I am blind—”

“Are you blind?” asked the stranger, anxiously.

“Yes, sir.”

“Since when?”

“I was born blind.”

Juan felt his companion’s arm tremble in his, and they walked along in silence. Suddenly the man stopped and asked in a voice husky with emotion,—

“What is your name?”

“Juan.”

“Juan what?”

“Juan Martínez.”

“And your father was Manuel Martínez, wasn’t he,—musician of the third artillery band?”

“Yes, sir.”

The blind one felt the tight clasp of two powerful arms that almost smothered him, and heard a trembling voice exclaim,—

“My God, how horrible, and how happy! I am a criminal, Juan! I am your brother Santiago!”

And the two brothers stood sobbing together in the middle of the street. The snow fell on them lightly. Suddenly Santiago tore himself from his brother’s embrace, and began to shout, intermingling his words with interjections,—

“A cab! A cab! Isn’t there a cab anywhere around? Curse my luck! Come, Juanillo, try; make an effort, my boy; we are not so very far. But where in the name of sense are all the cabs? Not one has passed us. Ah, I see one coming, thank God! No; the brute is going in the other direction. Here is another. This one is mine. Hello there, driver! Five dollars if you take us flying to Number 13 Castellana.”

And taking his brother in his arms as though he had been a mere child, he put him in the cab and jumped in after him. The driver whipped his horse, and off they went, gliding swiftly and noiselessly over the snow. In the mean time Santiago, with his arms still around Juan, told him something of his life. He had been in Costa Rica, not Cuba, and had accumulated a respectable fortune. He had spent many years in the country, beyond mail service and far from any point of communication with Europe. He had written several letters to his father, and had managed to get these on some steamer trading with England, but had never received any answer. In the hope of returning shortly to Spain, he had made no inquiries. He had been in Madrid for four months. He learned from the parish record that his father was dead; but all he could discover concerning Juan was vague and contradictory. Some believed that he had died, while others said that, reduced to the last stages of misery, he went through the streets singing and playing on the guitar. All his efforts to find him had been fruitless; but fortunately Providence had thrown him into his arms. Santiago laughed and cried alternately, showing himself to be the same frank, open-hearted, jovial soul that Juan had loved so in his childhood. The cab finally came to a stop. A man-servant opened the door, and Juan was fairly lifted into the house. When the door closed behind him, he breathed a warm atmosphere full of that peculiar aroma of comfort which wealth seems to exhale. His feet sank in the soft carpet. Two servants relieved him of his dripping clothes and brought him clean linen and a warm dressing-gown. In the same room, before a crackling wood fire, he was served a comforting bowl of hot broth, followed by something more substantial, which he was made to take very slowly and with all the precautions which his critical condition required. Then a bottle of old wine was brought up from the cellar. Santiago was too restless to sit still. He came and went, giving orders, interrupting himself every minute to say,—

“How do you feel now, Juan? Are you warm enough? Perhaps you don’t care for this wine.”

When the meal was over, the two brothers sat silently side by side before the fire. Santiago then inquired of one of the servants if the Señora and the children had already retired. On learning that they had, he said to Juan, beaming with delight,—

“Can you play on the piano?”

“Yes.”

“Come into the parlor, then. Let us give them a surprise.”

He accordingly led him into an adjoining room and seated him at the piano. He raised the top so as to obtain the greatest possible vibration, threw open the doors, and went through all the manœuvres peculiar to a surprise,—tiptoeing, whispering, speaking in a falsetto, and so much absurd pantomime that Juan could not help laughing as he realized how little his brother had changed.

“Now, Juanillo, play something startling, and play it loud, with all your might.”

The blind boy struck up a military march. A quiver ran through the silent house like that which stirs a music-box while it is being wound up. The notes poured from the piano, hurrying, jostling one another, but never losing their triumphant rhythm. Every now and then Santiago exclaimed,—

“Louder, Juanillo! Louder!”

And the blind boy struck the notes with all his spirit and might.

“I see my wife peeping in from behind the curtains. Go on, Juanillo. She is in her night-gown,—he, he! I am pretending not to see her. I have no doubt she thinks I am crazy,—he, he! Go on, Juanillo.”

Juan obeyed, although he thought the jest had been carried far enough. He wanted to know his sister-in-law and kiss his nephews.

“Now I can just see Manolita. Hello! Paquito is up too. Didn’t I tell you we should surprise them? But I am afraid they will take cold. Stop a minute, Juanito!”

And the infernal clamor was silenced.

“Come, Adela, Manolita, and Paquito, get on your things and come in to see your uncle Juan. This is Juanillo, of whom you have heard me speak so often. I have just found him in the street almost frozen to death. Come, hurry and dress, all of you.”

The whole family was soon ready, and rushed in to embrace the blind boy. The wife’s voice was soft and harmonious. To Juan it sounded like the voice of the Virgin. He discovered, too, that she was weeping silently at the thought of all his sufferings. She ordered a foot-warmer to be brought in. She wrapped his legs in a cloak and put a soft cushion behind his head. The children stood around his chair, caressing him, and all listened with tears to the accounts of his past misery. Santiago struck his forehead; the children stroked his hands, saying,—

“You will never be hungry again, will you, uncle? Or go out without a cloak and an umbrella? I don’t want you to, neither does Manolita, nor mamma, nor papa.”

“I wager you will not give him your bed, Paquito,” said Santiago, trying to conceal his tears under his affected merriment.

“My bed won’t fit him, papa! But he can have the bed in the guests’ chamber. It is a great bed, uncle, a big, big bed!”

“I don’t believe I care to go to bed,” said Juan. “Not just now at any rate, I am so comfortable here.”

“That pain has gone, hasn’t it, uncle?” whispered Manolita, kissing and stroking his hand.

“Yes, dear, yes,—God bless you! Nothing pains me now. I am happy, very happy! Only I feel sleepy, so sleepy that I can hardly raise my eyelids.”

“Never mind us; sleep if you feel like it,” said Santiago.

“Yes, uncle, sleep,” repeated the children.

And Juan fell asleep,—but he wakened in another world.

The next morning, at dawn, two policemen stumbled against a corpse in the snow. The doctor of the charity hospital pronounced it a case of congealing of the blood.

As one of the officers turned him over, face upward,—

“Look, Jiménez,” said he; “he seems to be laughing.”

Featured: “A Recess on a London Bridge,” by Augustus Edwin Mulready; painted 1879.