It is said that when Charles V’s troops were victorious in Wittenberg (1547), some of his advisors urged him to exhume and burn Luther’s remains, which were in the chapel of the city castle. Magnanimous, the emperor simply replied: “He has found his judge. I wage war on the living, not the dead.” But respect for the graves of the dead, the desire for reconciliation and fraternization no longer seems to be on the agenda in the Spain of Pedro Sánchez. A New and striking demonstration of this is the latest twist in the Valley of the Fallen (Valle de los Caídos or Valle de Cuelgamuros) affair, with the exhumation of the remains of José Antonio Primo de Rivera, finally agreed upon by his family, in the face of pressure from the authorities and to avoid desecration of the grave by foreign hands. The mistake, for many people of good will, has been to persist in expecting sublime acts from the government when the source of the sublime has long since withered away. And so, the young founder of the Spanish Falange was exhumed and buried for the fifth time on the 120th anniversary of his birth (1903-2023). But why so much hostility, resentment and hatred towards José Antonio? Who was really the founder of the Falange?

Refusing Manichean History

For the craftsmen of the dominant historiography, neo-socialists or self-proclaimed “progressive” neo-liberals, the answer is as simplistic as it is repetitive: he was “a fascist, the son of a dictator,” and the case is closed. After thirty-five years of “conservative” or Francoist propaganda, followed by almost half a century of “progressive” propaganda, and despite the impressive bibliography that exists on the subject, José Antonio remains the great unknown or misunderstood figure of contemporary Spanish history. For his opponents, admirers of the Popular Front, often covert glossers of Comintern myths, the young founder of the Falange was a sort of daddy’s boy, a cynical admirer of Italian fascism, a pale imitator of Mussolini. At best, for his opponents, he was a contradictory, ambiguous spirit, who sought in fascism a solution to his personal and emotional problems. Worse, again for his opponents, he was a servant of capital, an authoritarian, antidemocratic, ultranationalist, demagogic, arrogant, violent, racist and anti-Semitic personality, devoid of any intellectual quality. In addition to this absurd and grotesque accusation, his right-wing opponents are no less known for their grievances. According to them, he advocated a deliberately catastrophic policy, a strategy of civil war. In any case, for them, he was a misguided personality whose contribution to political life was null, marginal or negative insofar as he accelerated the national disaster. Some add, as if this were not enough, that José Antonio’s presence in the national camp, in the midst of the Spanish Civil War, would not have changed the course of events. If he had confronted the military, they say, they would have imprisoned or even executed him. If he had survived and been more successful, “he would most likely have been completely discredited.” And they do not hesitate to point out what they call a “contradiction between Joséantonian Falangism and Catholicism,” concluding, without hesitation, “as the Bible says, he who lives by the sword, dies by the sword.” But to affirm is not to prove.

For nearly half a century, I have been opposed to this caricatured, Manichean or soap opera history, to these reductive schemes contradicted by a considerable mass of facts, documents and testimonies. I know that the mere consideration of values, facts or documents, which contradict the opinion of so many so-called “scientific historians” (or rather camouflaged militants), leads ipso facto, at best, to silence and oblivion, and at worst, to caricature, to exclusion, to insult, to the accusation of complacency, of calculated legitimization, or even of disguised apology of fascist violence. But it doesn’t matter, the main thing is to say what needs to be said. A work, a historical study is worth its rigor, its degree of truth, its scientific value.

Once one has read much of the inexhaustible hostile literature, one must take the trouble to go to primary sources. In my case, the careful study of the Complete Works (Obras Completas de José Antonio Primo de Rivera, 2007) and the rigorous analysis of the documents and testimonies of the time have opened my eyes. The usual clichés about José Antonio Primo de Rivera, his person and his actions, or the repetition of truncated formulas and declarations taken out of context, in order to show the “poverty” of his analysis and the “weakness” of his thought, have not impressed me for a long time.

How can we grant a minimum of credibility to authors who keep silent, ignore or dismiss hundreds of balanced testimonies? Why is the anthology of opinions of personalities from all walks of life, published by Enrique de Aguinaga and Emilio González Navarro, Mil veces José Antonio (A Thousand Times José Antonio, 2003), so carefully ignored by so many so-called “specialists?” Why did Miguel de Unamuno, the greatest Spanish liberal philosopher of the time, along with Ortega, see in José Antonio “a distinguished mind, perhaps the most promising of contemporary Europe?” Why did Salvador de Madariaga, the famous liberal and anti-Franco historian, describe him as a “courageous, intelligent and idealistic” personality? Why would renowned politicians, such as the socialists and anarchists Félix Gordón Ordás, Teodomiro Menéndez, Diego Abad de Santillán and Indalecio Prieto, or famous liberal and conservative intellectuals, such as Gregorio Marañón, Álvaro Cunqueiro, Rosa Chacel, Gustave Thibon and Georges Bernanos, have paid tribute to his honesty and sincerity? Why would the most famous French Hispanist, member of the French Institute, Pierre Chaunu, a great connoisseur of Gaullism, have established a surprising parallel between the thought of Charles de Gaulle and that of José Antonio in a long article in Le Figaro (P. Chaunu, “De Gaulle à la lumière de l’Histoire,” September 4-5, 1982)?

Neither Right nor Left

José Antonio, as a precursor and disciple of Ortega y Gasset, had already denounced, ninety years ago, the two forms of moral hemiplegia: “To be of the right, as to be of the left, is always to expel from the soul half of what there is to feel. In some cases, it is to expel it entirely and to replace it by a caricature of the half” (Arriba, January 9, 1936). He wanted to create and develop a political movement animated by a synthetic doctrine, embracing all that is positive and rejecting all that is negative on the right and on the left, in order to establish a profound social justice so that the people return to the supremacy of the spiritual. The metaphysical, religious and Christian dimension, respect for the human person, refusal to recognize the State or the party as the supreme value, anti-Machiavellianism, and Classical and non-Hegelian foundation of the State are distinctive elements of his thought. With his sense of justice, solidarity and unity, while respecting diversity, with his strong sense of duty, José Antonio was both a traditionalist and a revolutionary.

He probably wanted to carry out a project that was too idealistic for his time: to nationalize the banks and the large public services, to attribute the surplus value of work to the unions, to carry out a profound agrarian reform in application of the principle: “The land belongs to those who work it,” to create a family, communal and union property. He wanted to establish individual, family, communal and union property, with similar rights.

Was his program reformist or revolutionary, realistic or utopian? One can debate this, but what cannot be said is that it lacked openness, generosity and nobility. José Antonio’s national-unionism failed miserably, but ultimately because he was a victim of the resentment, sectarianism and hatred of the Left as much as of the selfishness, arrogance and immobility of the Right. Censored, insulted, caricatured, imprisoned (three months before the July 18 uprising) and shot by the Marxist and anarchist Left on November 20, 1936, after a parody of a trial, the founder of the Falange, mocked and harshly criticized by conservatives and liberals before the war, was recuperated, manipulated, denatured and finally executed and buried a second time by Franco’s Right.

Alain Guy, a fine connoisseur of Spanish philosophy, and the political scientist Jules Monnerot, to mention only two prestigious French academics and intellectuals, affirmed that Joséantonian Falangism could not strictly speaking be reduced to “fascism” alone, that is, for serious historians and political scientists, to a certain model designating the imperfect similarities that can be established between the Italian and German phenomena. Nor was it reduced, they said, to Francoism, a regime and ideology whose character was above all conservative and authoritarian. Personally, I certainly do not put an equal sign between, on the one hand, José Antonio’s Falangism, Italian fascism, German revolutionary conservatism (before Hitler’s takeover) and, on the other hand, the three great hysterias of the twentieth century: National Socialist racism, the savage economism of neo-liberalism, or, the one that has undoubtedly caused more deaths than the two previous ones, Marxist socialism.

That said, it must be emphasized that José Antonio acted in a very specific time and space, the Spain of 1933-1936. His thought is not entirely reducible to the historical-cultural context, but it cannot be used to give concrete answers to current questions. Moreover, it contains elements that are questionable or even unacceptable today. Thus, its theorization of the “enlightened” minority, structured in clubs or parties, which would be the actor of development and revolution in the name of the people, is clearly marked and contaminated by the totalitarian conceptions inherited from liberal Jacobinism and Marxist socialism.

José Antonio and the French Non-Conformists of the 1930s

The Christian personalism of the founder of the Falange is very close to the thought of the French nonconformists of the 1930s (Robert Aron, Arnaud Dandieu, Jean de Fabrègues, Jean-Pierre Maxence, Daniel-Rops, Alexandre Marc, Thierry Maulnier, Emmanuel Mounier or Denis de Rougemont) who so influenced the future president of the French Republic, Charles de Gaulle (No less interesting is the comparison that can also be made with the thought of the founder of Fianna Fail, president of the Irish Republic, Éamon de Valera).

Ninety percent, if not all, of the personalist ideas of the French non-conformists of the 1930s, ideas most of which are surprisingly current, and which first permeated the most original circles of the Vichy regime, as well as those of most of the non-communist networks of the Resistance, were shared by the young leader of the Falange.

To be convinced of this, it is enough to recall here the main ideas of this French personalist current (see: Jean-Louis del Bayle, Les non-conformistes des années trente, 1969). There is first of all the criticism of the representative, parliamentary democracy, synonymous of lies, of absence of character, of dishonorable behavior, of control of the press and the democratic mechanisms, of regime in the hands of an oligarchy of ambitious and rich men. Then there is anti-capitalism, whose roots are philosophical and moral rather than economic or political. It is the virulent criticism of “laissez faire, laisser passer,” which leads to the transformation of society into a veritable jungle where the demands of the common good and of justice are radically ignored. It is the denunciation of the submission of consumption to the demands of production, itself submitted to speculative profit. It is the rejection of the absolute primacy of profit and financial speculation, as well as of the domination of banks and finance. It is the rejection of usury as a general law, of the triumph of money as the measure of all human action and of all value. Finally, it is the reproach of attacking initiative and freedom, of killing private property by concentrating it in fewer and fewer hands: “Liberalism is the free fox in the free henhouse.”

This personalist, non-conformist current declared itself “neither of the right nor of the left,” “neither communist nor capitalist;” it wanted to fight for the “dignity of the human person,” for “spiritual values,” and defended “the third way;” it wanted to extend individual property by multiplying non-state collective properties; it wanted to reorganize credit by entrusting it to banks, managed by professional organizations or consumer associations. His main criticism of capitalism was summed up in two words: materialism and individualism. “Drink, eat and sleep is enough;” in that, affirmed the nonconformists, Marxism does not break with capitalism, but prolongs its defects. The ultimate goal was not happiness, comfort and prosperity, but the spiritual fulfillment of man. They advocated simultaneously the need for a revolution of institutions, an economic and social revolution and a spiritual revolution. Fundamental to them was the idea that any upheaval of structures would be useless if it were not accompanied by a moral and spiritual transformation of man, beginning with that of the supporters of the coming revolution.

This brief review of the personalist spirit of the French nonconformists of the 1930s leads to the conclusion that there is not a single one of their proposals that does not find an echo in the writings and speeches of José Antonio. Primo de Rivera was neither a Hegelian, nor a racist, nor an anti-Semite. He did not place the state or race at the center of his worldview, but man as the bearer of eternal values, capable of being saved or lost. He did not advocate a materialistic and totalitarian revolution (collectivist-classist, statist or racist), which seeks to reduce social and spiritual reality to a single model, but a spiritual, total revolution, at once moral, political, economic and social—a Christian-personalist revolution, integrating all people and serving all people.

The influence of Italian fascist ideology on the thought and style of José Antonio is undeniable, but there are also other influences no less important, such as traditionalism, liberalism, anarchism and Marxism-socialism. Many judge José Antonio’s admiration for Mussolini severely. It is true that at the beginning of his brief political career, like many other politicians and intellectuals of his time, such as Churchill or Mounier, he showed a real esteem and even enthusiasm for the social achievements of the Duce. But we must not forget that the state totalitarianism of Mussolini’s regime was infinitely less bloody than the totalitarianism of class or race. All modern ideologies have been at the origin of flagrant crimes, and none can claim to be more human than the others. But there are degrees of horror, and when it comes to judging the founder of the Falange, a minimum of decency and rigor is required.

José Antonio and Che

Several authors have ventured to draw a parallel between José Antonio and the most emblematic figure of twentieth-century revolutionary romanticism, the Leninist-Maoist guerrilla, Ernesto Guevara. The similarities, however, are imperfect. Both exalted the virtues of courage, loyalty and fidelity. Both symbolized the altruism of youth. Both despised luxury, lavish tastes and the ostentation of wealth. Both rejected the economic and social order where only money reigns, where society is abandoned to the sole rules of profit and triumphant egoism, with their inevitable corollaries of speculation, greed and corruption. Both disregarded fear, despised money and were driven by a passion for duty. But the similarities end there.

José Antonio was a convinced Catholic. Che had no metaphysical concerns and was hostile to all religious beliefs. A materialist and atheist, Ernesto Guevara despised what Nietzsche denounced as “the weaknesses of the Christian.” Fanaticism, sectarianism, harshness, hatred of the Other, revolutionary demagogy are traits that Che shared with Robespierre, Lenin, Hitler, Stalin and Mao. The most terrible thing about Che is the mixture of personal asceticism and the ability to scourge others, the certainty of always being right, the abstract hatred, the cold political cruelty. For him, friends were friends only if they thought like him politically. Like his master, Lenin, political combat legitimizes all means: cunning, manipulation, cynicism, extreme violence, insults, invective, slander, libel, subsidies to the enemy of the fatherland, theft of inheritances, robberies and summary executions. Che loved people not as they are, with their greatness and weaknesses, but as the revolution would have transformed them. He was an exterminating angel. He expressed his feelings more easily for the death of an animal than for that of an enemy. It is difficult to imagine José Antonio ordering the summary execution of more than a hundred opponents, as Che did in the fortress of La Cabaña. It is equally difficult to imagine him writing, like Lenin to Gorky (September 15, 1922), these repugnant lines about intellectuals to deplore the delay in their executions: “The intellectuals, lackeys of the bourgeoisie, think they are the brains of the nation. In reality, they are not its brains, they are its shit” (see: Hélène Carrère d’Encausse, Lénine, 1998, p. 586).

The Ethics of José Antonio

José Antonio had a sense of measure and balance; he knew that in politics, the absolute refusal of any compromise (which is not the abandonment of principles in favor of opportunism) always leads to implacable terror. Republican and democrat of reason, he rejected any nostalgia of the past, whether monarchist, conservative or reactionary. He had no more the excessive taste of the military for order and discipline than the irresistible attraction of the actor or artist for the stage and comedy. He was neither Franco (for whom he had little sympathy) nor Mussolini. Stupid as it may seem, José Antonio had a marked inclination for goodness; a “goodness of heart,” as the master Azorín rightly pointed out, which, together with a high conception of justice and honor, an unquestionable physical courage, a constant intellectual preoccupation, a charisma or magnetism of a leader, and finally, a keen sense of humor, made him inevitably likeable.

Contrary to the Jacobin utopians and socialist-Marxists, José Antonio wanted to base his system on the person and to defend cultural, regional and family specificities. He did not seek to make the Other, an Other Me, but simply to accept him, to understand him and to convince him to collaborate with him for the good of the whole national community. When the Spanish Civil War broke out, in the face of the avalanche of hatred and fanaticism, of iron and blood, he resisted and stood up almost alone. From his cell in Alicante, he offered his mediation in a last attempt to stop the barbarism. But it was a lost cause, and it was rejected. He died with dignity, without hatred, with a serene soul, like a Christian hero, at peace with God and men. In his will he wrote: “I forgive with all my heart all those, without exception, who may have harmed or offended me, and I ask all those to forgive me to whom I may owe the reparation of some wrong, be it great or small” (November 18, 1936). In the political world of the 20th century, notable personalities abound, but it is difficult to find more noble ones. He was a kind of last Christian knight.

That said, historically, José Antonio’s merit is that he tried to critically assimilate, from a deeply Christian position, the socialist revolution while dissociating spiritual and communitarian values from the reactionary right. And one of his most original characteristics was to appear on the political scene of his time with a new rhetoric, a new way of formulating politics, with an original and attractive language for the young.

Lies and Truths

It is now appropriate to examine the accusations of violence and anti-democracy that are so often levelled at him. Invariably, he is reproached with a phrase that he himself described as unfortunate: “When Justice and the Fatherland are undermined, there is no other admissible dialectic than that of fists and guns.” But it is still necessary to quote it in its entirety and to put it into perspective. Let’s not forget the constant exalted, inflammatory and anti-democratic declarations of his opponents, starting with those of the “Spanish Lenin,” the socialist revolutionary and Marxist Largo Caballero, who called for the “dictatorship of the proletariat” (Cádiz, May 24, 1936), and declared “we are not different from the communists” (Bilbao, April 20, 1934); “I want a republic without class struggles, but for that, one must disappear” (Alicante, January 25, 1936); or the slogans repeated tirelessly by the socialists newspapers Claridad and El Socialista: “May the parliamentary republic die,” “Hate the criminal bourgeoisie to death.”

Let’s contextualize the alleged Joséantonian violence. The Joséantonian Falange was responsible for sixty to seventy murderous attacks between June 1934 and July 1936. But in the same period, it suffered about 90 deaths in its ranks (there were 2,000 to 2,500 deaths during the Second Republic). From the day after its foundation, in October 1933, the Joséantonian Falange suffered a dozen deadly attacks. These were not street fights, but terrorist attacks, carried out by socialists, communists and anarchists, to physically eliminate the distributors of the Spanish Falange (FE) weekly. The propagandistic image against the Spanish Falange (FE), as the main group whose terrorist action provoked the Civil War, is radically false. It was for his refusal to enter the cycle of violence for months that José Antonio was nicknamed “Simon the Gravedigger” by the right, and that his party and its militants received the nicknames of “Spanish Funeral” (FE) and “Franciscanists.” In reality, it was only after eight months of waiting that the Joséantonian Falange reacted violently. The trigger was the death, on June 10, 1934, of a 17-year-old Falangist student, Juan Cuellar, murdered in the Casa de Campo by a group of Madrid socialists. To top it all off, the socialist activist Juanita Rico urinated on the corpse of her victim and the father of the young Cuellar was unable to recognize his son’s face, which had been stomped, crushed and mutilated.

In reality, a presentation of the facts that ignores the Bolshevization or revolutionary radicalism of the socialist party, the development of the socialist and communist paramilitary apparatus, the incoherence of the liberal republicans, and the reactionary immobility of the conservatives, in order to better demonstrate that the Joséantonian Falange was the main cause of the violence during the Republic and, consequently, of the final breakup, is simply fraudulent. Violence was never a postulate of the Joséantonian ideal. It was violence to repel aggression or to defend rights or timeless truths (“bread, country and justice”) when all other instances were exhausted.

Anti-capitalist, anti-socialist and anti-Marxist, José Antonio was certainly that. But was he anti-parliamentary and anti-democratic? Why would he have said: “But if democracy as a form has failed, it is mainly because it has not been able to provide us with a truly democratic life in its content… Let us not fall into the extreme exaggerations which translate the hatred of the superstition of suffrage into contempt for everything democratic. The aspiration to a democratic, free and peaceful life will always be the objective of political science, above all else” (see Conference in Madrid: “La forma y el contenido de la democracia”—”The Form and Content of Democracy,” 1931). It is ridiculous to transpose the present image of Spanish democracy to the past. The present situation cannot be compared to the period before the Civil War. Then there were many revolutionaries and convinced conservatives, but very few tolerant and peaceful democrats. Respect for the other was not the order of the day.

Was José Antonio a putschist, as many authors claim? It is well known that coups d’état, whether moderate or progressive (and much more rarely conservative), were a prominent feature of political life in Spain (and also in much of Europe) during the 19th and early 20th centuries. In the Spanish Peninsula, after the French invasion and from 1820 onwards, no less than 40 major pronunciamientos or coups d’état, and hundreds of very minor ones, took place. It is more than likely that José Antonio was marked, even contaminated, by the putschist tradition of 19th century liberalism and by the dual putschist tradition of early 20th century anarchism and socialism. But what is certain is that his ephemeral and incongruous “insurrection” project, suggested only once at the Gredos meeting (June 1935), was never more than a circumstantial, theoretical and imaginary response—without the slightest principle of application—to the serious socialist insurrection of October 1934.

Who were the real theoreticians and technicians of the dictatorship from the end of the 19th century in Spain, if not the epigones of the praetorian tradition of liberalism, such as the republican-democrat Joaquín Costa, not to mention the socialists and Marxists who were then openly doctrinaire or advocates of the dictatorship of the proletariat, or, more precisely, of the dictatorship of the Party over the proletariat. José Antonio did not doubt the sovereignty of the people. He wanted to improve the participation of all citizens in public life. But to individualist and liberal democracy, to collectivist and popular democracy, he preferred organic, participatory and referendum democracy, which, according to him, was more capable of bringing the people closer to the rulers. In the Europe of the inter-war period, this choice appeared to many as possible, balanced and reasonable. Moreover, if this choice had not been considered by many to be realistic and thoughtful, why would so many famous leaders, whose political convictions were the opposite of José Antonio’s, such as the first Fidel Castro or the Prime Minister José María Aznar, have been attentive readers and admirers of the Complete Works in their youth?

Contrary to what is so often repeated, José Antonio admired, even with a certain naivety, the British parliamentary tradition. Some Falangist activists, who did not appreciate the interventions of the founder of the FE in Parliament, did not fail to criticize his “excessive taste for parliamentary debates.” In reality, José Antonio was a supporter of organic democracy, as were Julián Sanz del Río, Nicolás Salmerón, Fernando de los Ríos, Salvador de Madariaga and Julián Besteiro, to name just a few Spanish liberal and socialist authors.

On the other hand, José Antonio was much more patriotic than nationalist. The nation is not, according to him, a race, a language, a territory and a religion, nor a simple desire to live together, nor the sum of all these. It is above all “a historical entity, differentiated from the others in the universal by its own unity of destiny.” “We are not nationalists,” he said in Madrid (November 1935), “because to be nationalist is pure nonsense; it is to implant the deepest spiritual impulses on a physical motive, on a simple physical circumstance; we are not nationalists because nationalism is the individualism of the peoples” (Discurso de clausura del Segundo Consejo nacional de la Falange—Closing speech of the Second National Council of the Falange), Cine Madrid, November 17, 1936).

Some authors have tried to detect in him a late evolution and a rapprochement, almost in extremis, with the theses of National Socialist Germany. They rely on a work dated August 13, 1936, Germánicos contra bereberes (Germanic vs. Berber), written in the middle of the Spanish Civil War, in his cell in Alicante and found among his papers after his death. In it he expresses a superficial and reductive ethnocultural vision that does not stand up to rigorous historical criticism. He tries to explain the Reconquista as a confrontation between two archetypes, the “Germanic spirit” and the “Berber spirit;” but at the same time he seems to recognize the Hispanic-Romanic-Visigothic fusion. This work contains inaccuracies and assertions that are later totally denied and refuted by him in his will. However, it is worth recalling here that this type of ethnocultural interpretation was widespread in his time and among authors with contradictory beliefs. Most historians of nation-states conceived of their origins as an opposition between natives and conquerors. Thus, the historiography of France constantly oscillated between the thesis of a Frankish origin (Clovis, the Frankish king) and that of a Celtic and Gallic origin (Vercingetorix) or Gallo-Roman when Rome was taken into account. For the aristocrat Montesquieu, the liberties were of Germanic origin. But to return to the alleged racism of the work, Germanic vs. Berber, it should be remembered that the same abusive accusation could be made against works of philosophers and historians Ortega y Gasset, Américo Castro or Sánchez-Albornoz.

José Antonio was clearly anti-separatist, but he never succumbed to the Jacobin and centralizing temptation. His speech to Parliament on November 30, 1934, is a testament to this. “It is clumsy to try to solve the Catalan problem by considering it artificial… Catalonia exists in all its individuality, and many regions of Spain exist in their individuality, and if one wants to give a structure to Spain, one must start from what Spain really offers… That is why I am one of those who think that the justification of Spain is found in something else: Spain is not justified by a language, nor by a race, nor by a set of customs, but… Spain is much more than a race and much more than a language… it is a unity of destiny in the universal… That is why, when a region asks for autonomy… what we must ask ourselves is to what extent the consciousness of the unity of destiny is rooted in its spirit. If the consciousness of the unity of destiny is well-rooted in the collective soul of a region, it is hardly dangerous to give it the freedom to organize its internal life in one way or another” (España y Cataluña, Parliament, November 30, 1934).

Let us also recall in passing the alleged machismo or antifeminism of José Antonio for having expressed one day the desire of a “joyful Spain and in a short skirt.” It is perhaps not useless to recall here the name of one of the most outstanding figures of Spanish feminism, the lawyer Mercedes Formica. It is to her that we owe the deep reform of the Spanish Civil Code in favor of the rights of the women in 1958. A Falangist from the beginning in the 1930s, she was a loyal follower of José Antonio throughout her life (who appointed her national delegate of the SEU union and member of the Political Junta), which makes her the victim of a fierce omertà today. In her memoirs, Formica sweeps away the propagandist myth of an anti-feminist José Antonio, demonstrating its falsity and imposture.

As for the so-called imperialism of the founder of the FE, the arguments of those who support it are extremely fragile. There is no territorial claim in the Complete Works. According to José Antonio, in the twentieth century the Spanish empire could only be spiritual and cultural. It goes without saying that one would look in vain for anti-Semitic or racist overtones in his words. He uses the term “total state” or “totalitarian” five times, not without errors and clumsiness, but he does so clearly to signify his desire to create a “state for all,” “without divisions,” “integrating all Spaniards,” “an instrument in the service of national unity.”

Equally surprising is José Antonio’s opinion on fascism. He expressed it unambiguously in 1936: fascism “claims to resolve the disagreement between man and his environment by absorbing the individual into the collective. Fascism is fundamentally false—it is right to presuppose that it is a religious phenomenon, but it wants to replace religion with idolatry” (Cuaderno de notas de un estudiante europeo—Notebook of a European Student, September 1936). As for his Catholic convictions, they are beyond question. The last and clearest manifestation of these can be found in the above-mentioned testament that he wrote on November 18, 1936, two days before his execution.

A Variant of the Third Way

The Joséantonian Falange is a variant of the Third Way ideologies, which many doctrinaires, theorists and politicians have defended or advocated since the end of the 19th century. Historically, personalities as diverse as De Gaulle, Nasser, Perón, Chávez, Clinton or Blair have referred to the Third Way. But their allegiances, despite sometimes misleading appearances, are not the same. There are two different political filiations, two directions that never meet. Beyond times, places, words and men, the supporters of the authentic Third Way pursue tirelessly the overcoming of the antinomic thought. They want, as José Antonio said, to build a bridge between Tradition and Modernity. The synthesis-overcoming, the need for reconciliation in the form of overcoming, is for them the main objective of all great politics. This is, after all, the root of the almost metaphysical hatred that their opponents feel for them. This being said, since José Antonio’s thought constitutes one of the members of the vast family of Third Way ideologies, it is all the more legitimate to ask the question: “What did José Antonio really leave us?” To answer this question, I will once again use the words of the Basque philosopher Miguel de Unamuno, which conclude my early book on José Antonio, prefaced in Spain by the economist Juan Velarde Fuertes: “He has bequeathed himself, and a living and eternal man is worth all theories and philosophies.”

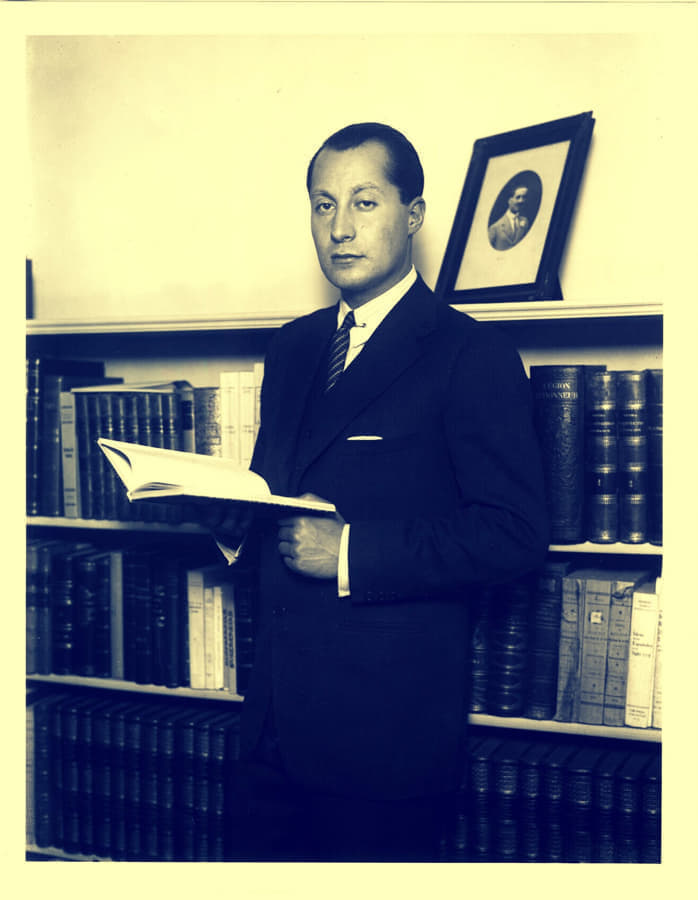

Arnaud Imatz, a Basque-French political scientist and historian, holds a State Doctorate (DrE) in political science and is a correspondent-member of the Royal Academy of History (Spain), and a former international civil servant at OECD. He is a specialist in the Spanish Civil War, European populism, and the political struggles of the Right and the Left – all subjects on which he has written several books. He has also published numerous articles on the political thought of the founder and theoretician of the Falange, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, as well as the Liberal philosopher, José Ortega y Gasset, and the Catholic traditionalist, Juan Donoso Cortés.