Has Jesus been “deified” by Christians? This debate, which is quite recurrent in academic circles, is essentially determined by an external view of what Christians are supposed to believe. The idea is to compare the divine dimension of Jesus as expressed in the New Testament with the divinization of the Roman emperors after Augustus—or possibly with forms of divinization in this or that other ancient civilization. However, from comparison we often pass quickly to conflation.

Let us address the question head-on. Does the New Testament “deify” Jesus in any way, or is it something else? This debate is not incidental; it has serious consequences, six of which are defined and analyzed below, even if not everyone will readily recognize them as such. It is important to point out at the outset to what extent they imply each other in a logical sequence, from “B” to “G,” if we state “Proposition A” as the idea of the divinization of Jesus.

Let us begin by mapping Proposition “A”:

A: The presumed Christian idea of divinizing a man comes from, or corresponds to, a tendency in the Greco-Roman world, or more broadly in the pagan world—it is also found in various forms in Eastern Gnosticisms, the question remaining open of locating the origin of the latter in actual history.

On “A” is then built an entire sequence of logical inferences.

From Proposition “A,” the following is then deduced:

Proposition B: Since this presumed “divinization” could in no way be the work of Jews, it was therefore the work of non-Jews, namely of “Christianized” pagans (of the Roman Empire).

From Proposition “B,” it is then deduced that:

Proposition C: It is therefore these pagans who composed the Gospels, which are thus late (after the year 70 AD; this stretch of time needed to manufacture the “divinization”). And, of course, these pagans could only have composed the Gospels in Greek.

[An impressive and lavish publication of more than 700 pages, subsidized by the French Ministry of Culture, Après Jésus, l’invention du christianisme {After Jesus: The Invention of Christianity} (edited by Roselyne Dupont-Roc and Antoine Guggenheim, Albin Michel, 2020), largely defends this thesis of the late fabrication of a Christianity that does not owe much to Jesus, “except for a meal in memory of him, and a prayer, the Lord’s Prayer” (we read on page IV). The rest has been “invented,” which requires time—on pages 21-22, Mark’s Gospel is dated 71 AD, Matthew’s and Luke’s between 80 and 85 AD, and John’s 98 AD.]

And a further consequence of “C”: Thus, before these Greek compositions [the Gospels], the Jewish Christian communities produced nothing (or almost nothing); and the traces of this “almost nothing” in the Greek Gospels would suggest that they saw Jesus simply as a man.

It is then deduced from Proposition “C” that:

Proposition D1: It was Paul, whose writing period we know (between 51 and 64), who first deified Jesus; [Among the many discussions on this subject, this one is quite comprehensive.]

Proposition D2: Under the impulse of the Emperor Constantine, the Council of Nicaea (325 AD) contributed in a determining way by making the dogma of the “Trinity,” in answer to the Arianism which made of Jesus simply a kind of superman.

From Proposition “D,” it is then deduced that:

Proposition E: Since there were Christian communities speaking Aramaic (the language of the Jews of the first century)—and even today, at least one million Aramaic speakers—and since they always professed the divinity of Jesus, they could only have come to exist in dependence on Greek Christianity, and therefore not before the end of the third century; they must only be an outgrowth of Greek Christianity in the Syriac East of the Roman Empire, or the result of the deportation of some Greek-Roman populations to the Parthian Empire.

From Proposition “E,” it is then deduced that:

Proposition F: The Aramaic (or Syriac) texts of the New Testament or Peshitta NT were therefore translated from Greek. [Peshitta simply means, “without gloss.”] Thus, these texts must be of no interest. For an exegete, it is therefore unthinkable (and dangerous for his career) to spend time systematically comparing the versions in these two languages in order to find out which is the most original. One does not do research for which one already knows the answer.

From Proposition “F,” it is then deduced:

Proposition G: The Semitic-speaking groups that held Jesus to be a man (not a God) would be, according to research, the true Christians who retained the Christianity of the Apostles. These groups, sometimes called “Judeo-Christian sects,” are referred to as either “pre-Pauline” or “pre-Nicene.” Some traces of them are to be found in the Qu’ran (which is convincingly argued—but are they pre-Pauline or later groups?).

The logic of this sequence of seven propositions from A to G is unstoppable. It rests fundamentally on proposition “A”: to speak of the divinity of Christ is to speak of his “divinization.” We shall therefore look carefully at this postulate, and then, more briefly, at its six successive implications, in particular to see if they correspond to what we know of historical reality.

PROPOSITION “A”

What do Christians believe? Is Proposition A a legitimate interpretation of their faith, or not?

In the context of this analysis, the postulate of A can be presented as follows:

“Christians believe that God is present in a man (Jesus)” means “Christians have deified a man (Jesus).” Such an understanding of the first proposition would be legitimate, if there were not a completely different understanding than that of A. Indeed, “God is present in a man (Jesus)” is clearly to be understood as meaning “God has made himself present in a man (Jesus);” the totality of Christian writings indicating this. Is it rational to arbitrarily impose another understanding?

If we analyze the problem further, we perceive that the two understandings are radically opposed. The Christian faith undoubtedly mentions a descending movement (on the part of God; more precisely what has been called “Incarnation”); whereas Proposition A supposes an ascending movement (raising a man to become “god”)—it obviously confuses a “descending” movement with an “ascending” one.

We can therefore speak of a serious misunderstanding. But this is not a new phenomenon. Indeed, the faith of the Hebrews was the victim of many misunderstandings on the part of the surrounding peoples. For pagans inclined to “deify” humans, what could the Jewish (and Biblical) expectation of a God who comes to visit His people mean? In their mind, what was the value of the Temple in Jerusalem, which was the place of an invisible and impalpable presence, following the initiative of a God to “come down?” And what could they think of the idea—or rather the hope—that this God would really come to visit His people, according to prophecies where the how is not at all clear? Moreover, were they happy that the Jews considered their practice of putting a statue in a temple and then declaring it a “god” an abomination? Throughout history, Hebrews have sometimes been tempted to reconcile these irreconcilable positions—one might say that this temptation to amalgamate Jewish and pagan cults is the ancestor of Proposition A.

This can be said all the more so since the answer to this amalgam was given in antiquity already, by a Jew. In the early 40s AD, the Alexandrian Jewish philosopher Philo († 45) noted in a passage of his Legatio ad Caium, after coming to Rome and seeing the emperor Caius Caligula there publicly displaying himself disguised as Jupiter: “God could rather change into a man than a man into God.”

As a Jew, he was shocked by this masquerade (he wrote it after 41 AD, once Caius had died). This philosopher of Alexandria perfectly understood and expressed the radical opposition existing between the Jewish religious vision and that of the pagans. He may have formulated it on his own, but it is also possible that he had heard of the Christian faith—in Alexandria he could have met many Jewish disciples of the Apostles. [According to the Acts of the Apostles (18:24-25), a former disciple of John the Baptist, Apollos, a native of Alexandria, was traveling through Asia Minor around the year 44 to speak about Christ—Paul, in Antioch, spoke to him about the baptism in the Holy Spirit, which he had not heard of. Thus, this Apollos had not yet met any of the Apostles or any of their disciples; but, the text says, “he had been instructed in the way of the Lord”—in Alexandria?] Philo’s expression, “change into a man” corresponds in fact to the way of speaking of the first Jewish Christians—it is found in the apocrypha.

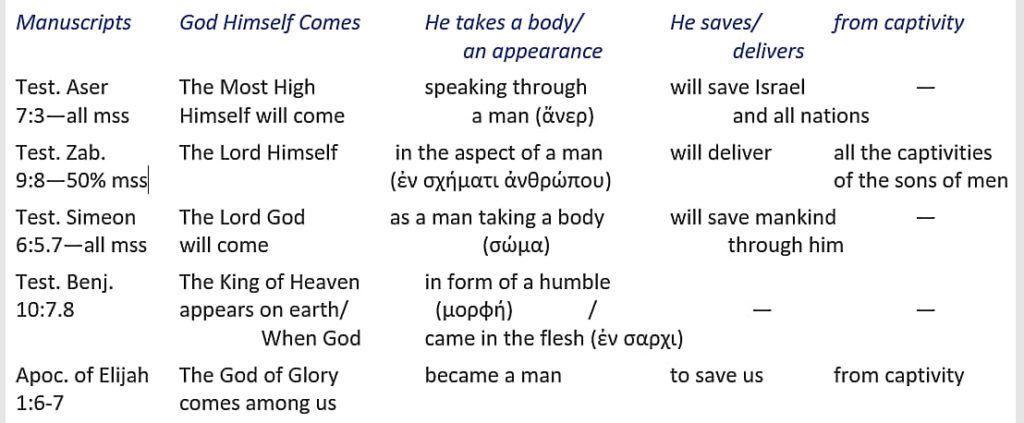

[In some “apocrypha,” one can read very similar formulations. Those given below are essentially taken from the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs. For this very complex question, see Le messie et son prophète, Vol. I, 2005, section 1.4.2.1, “Thématique de la venue de Dieu et double Visite” [Theme of the Coming of God and the Double Visit], pp. 166ff.]

In an amplified and clarified form, it is found in the New Testament, notably in this passage by Paul, where he speaks of the “descent” of God into human nature: “Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form…” (Letter to the Philippians 2:6-7).

No parallelism should therefore be intellectually possible between the Christian faith and pagan cults. It is by virtue of an internal logic, foreign to Christianity, that a system of thought can produce this confusion. To illustrate the problem, let us take the example of Islamic discourse.

For Islam, the Qur’anic text is literally revealed by God through the word of an angel dictating the text to the messenger (rasul) Muhammad. One of its verses reads as follows:

“When God says: ‘Îsa (Jesus), son of Mariam, did you say to people:

Take me and my mother for two deities, beside God?” (Sura 5, verse 116)

The internal logic of Islamic discourse therefore requires that Christians have Jesus, Mary and God as the Trinity—it is written in the Qur’an, so God has said it literally. This is taught everywhere in Islam, at least where Christians have little influence, so that this assertion is not immediately ridiculed. And if a Christian disputes this, the answer to him is already prepared in the Qur’an: “See how they lie against themselves” (Sur. 6, v.24).

In fact, the ancient Muslim commentators [Tabari, al-Baydawi, al-Zamahšarî, al-Jalalayn and other lesser-known scholars all indicate that this verse (5:116) refers to the Holy Spirit and not to the Virgin Mary. See Azzi Joseph, Le prêtre et le prophète: aux sources du Coran, p.169]—still knew that the expression “mother of Jesus” (here, “my mother”) refers to the Holy Spirit, according to a way of speaking proper to the tradition of the Aramaic Church (even today), and as the oldest Syro-Aramaic spiritual writings testify. [For example, in Saint Aphrahat (known as the Wise Man of Persia). The “maternal” dimension of the Spirit is so common in the theology of the Church of the East that Saint Aphrahat applies it to the Christian: there is a danger, he writes, that the one who marries forgets “his Father and the Holy Spirit his mother” (The Demonstrations [written between 336 and 345)].

The irony of verse 5:116 relates to the role of judge of Christians, attributed to Jesus, and not to a classical Trinitarian formulation in the Syro-Aramaic context. But a serious problem of internal Islamic and Islamological logic arises. Indeed, if this context constitutes the obligatory explanation of a verse of the Qu’ran, it also determines the framework of the birth of Islam—one is thus led to consider for Islam an original place in northern Arabia. This is unacceptable for Islam. Nor did islamology, at least for a hundred and fifty years, want a place other than Mecca, since it took the Islamic discourse as its starting point. In fact, Islamologists even invented the existence of “Mariamites” to justify the literal Islamic understanding of this verse (5:116). This invention, based on an error, has been taken up by current Islamic propaganda to comment on this verse by mocking the faith of Christians. [Cf. the presentation by Hichem Djaït in Jésus et l’islam. Indeed, it happens that in the suburbs and living only among themselves, Muslims never see a single Christian; so they believe anything about the Christian faith.] It was not until the year 2005 that this gross error was denounced, although it would have been enough for any researcher to go and ask any Aramaic (Chaldean or Assyrian) Christian for this error to be disproved.

We can see, therefore, that internal logic can prevail over knowledge or simple information, even in a milieu of researchers. This is also the case of the confusion between the Christian faith and pagan conceptions, which concerns us here. It is possible that convenience has something to do with it—one always brings back what one knows badly to what one already knows. Hearing about groups of Jewish descent who denied the divinity of Christ early on, often in summary form, some scholars have concluded that their purely human conception of Jesus is the original, true Christianity; and, therefore, that to speak of the presence of God in Jesus is a later belief, influenced by Greek pagan thought. This is logical, but wrong—the so-called “Judeo-Christian” groups to which they refer in this discussion are in fact “ex-Judeo-Christians,” in the sense that they had first been Christians then Jews. Let us read what the apostle John writes in his first letter about these ex-Judeo-Christians who “deny the Father and the Son”:

“They went out from us, but they did not belong to us; for if they had belonged to us, they would have remained with us. But by going out they made it plain that none of them belongs to us” (1 John 2:19).

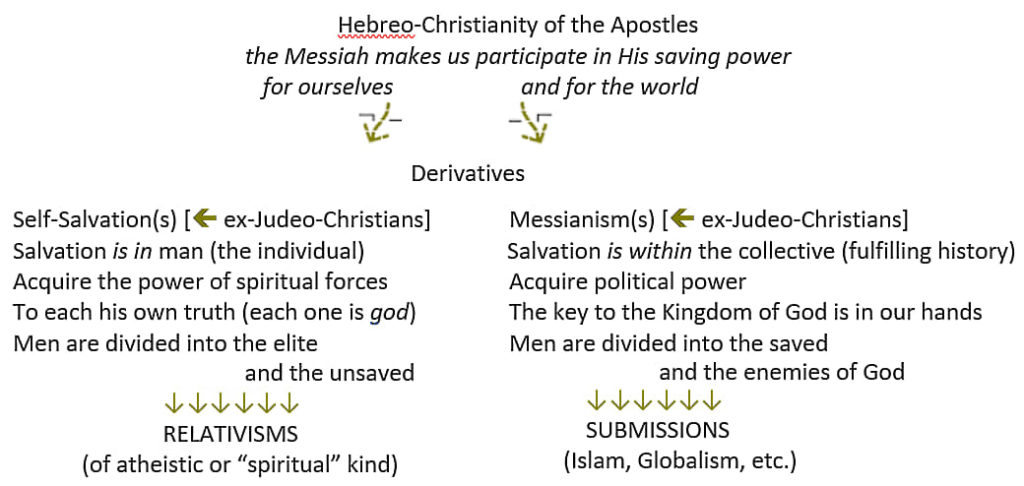

What is generally overlooked in the discussion is that those Jewish Christians who first adhered to the message of the Apostles and then turned it around to do something else were thus creating a new religious phenomenon, which would even be the source of many subsequent avatars. The opposition is not, therefore, between a Jewish monotheism and a pagan polytheistic influence—but between the Christianity of the Apostles, which has a Jewish foundation, and the doctrines opposed to that of the Apostles, which also have a Jewish foundation, and which warrant the designatio of “post-Christian.”

In fact, the confusion inherent in Proposition A has created a vagueness that obscures a whole area of research on the formation of the oppositions to the Apostles. The Adversus haereses of St. Irenaeus of Lyon, which has been available to us since the mid-sixteenth century (this book, along with The Demonstration of Apostolic Preaching, previously unknown), still does not seem to be taken as a reference book for the study of early Christianity and the groups that derived from it.

It appears, therefore, that Proposition “A” does not present the faith of the Apostles, but rather presents a kind of inversion of it. This is unfortunate from a scientific or even a rational point of view. And the successive consequences which follow from it, and which form a set of convictions quite widespread in the academic world, are serious.

Let us review these consequences, B to G.

Proposition B

This proposition follows from A: the “divinization” of Jesus must have been done by non-Jews, namely by “Christianized” pagans (from the Roman Empire).

If there was no “divinization” of Jesus, the question of its alleged authors is settled. However, a word should be said about the historical framework, the lack of knowledge of which favors adherence to proposition B.

The Apostles were Jews, as were the first Popes and the vast majority of Christians for at least a century. As Paul explains, non-Jews were added to the strong Hebrew-Aramaic olive tree—and it had to be a strong olive tree because, from the beginning, the Apostles and their followers went to evangelize every part of the world then accessible, as far as India and China. The result was very quickly a diversity of communities; the common Hebrew-Aramaic “olive tree,” both Biblical and cultic, ensured unity, especially liturgical unity (the Indians of Saint Thomas still celebrate in Aramaic today). When one discovers the extent of the Hebrew-Aramaic Christianity of the Apostles in the world of that time, the idea of an influence of “Christianized pagans” leaves one scratching one’s head.

Proposition C

Preceding from the previous one, this proposal assumes that it was these Christianized pagans who composed the Gospels, and therefore late (after the year 70 AD, the time of the fabrication of the “divinization”); and, of course, they can only have composed the Gospels in Greek. Consequently, the Jewish Christian communities produced nothing (or almost nothing) before these Greek texts, and the traces of this “almost nothing” in the Greek Gospels must suggest that they saw Jesus simply as a man.

Here we come to the fundamental problem of Western exegesis, posed by German Protestants from the end of the 16th century onwards. Because of their anti-Romanism, they turned exclusively to the Greek manuscripts, considering them a priori better than the Latin texts of the Catholic Church. Of course, other languages were not forgotten—in Pantagruel, Rabelais still indicates that it is necessary to learn Aramaic (Chaldean, he writes)—but, in practice, manuscripts in these languages were greatly lacking. These became available only at the end of the 19th century, because of the scarcity of contacts with Eastern Christianity before then; and in the 20th century, following the massive immigration of persecuted Eastern Christians, more numerous links were established.

Nevertheless, even today, no serious place is given to these Christians in the academic world among teachers, and the Gospels are still presented as the fruit of Greek writers—even though one is beginning to wonder whether they are not originally narrative compositions rather than redactions. In any case, almost no one has yet undertaken a systematic comparison of the best Greek manuscript texts (divided into seven or eight irreducible families, which poses a serious problem) with the Syro-Aramaic manuscripts (which form a single family). And one continues to affirm, in a dogmatic way, that the Aramaic texts were translated from Greek. [For example, here is a random example of this dogmatism: Muriel Dubié states peremptorily that “as early as 170, the Gospels were translated from Greek into Syriac”]. Those who have doubts and want to compare the texts, like the Protestant Jan Joosten, risk a lot.

Rationally, it is however very difficult to believe that the Jewish Christians did not compose stories in Aramaic, which was their language (and that of Jesus), when they were evangelizing in all directions of the world and when Aramaic (and not Greek) was the lingua franca, the English of its time. And that’s not all. The Jews were part of an oral civilization, even though all men had to be more or less able to read the sacred writings during the synagogal worship. Thus, for the Christian Jews, if the important thing was the transmission by word of mouth and from heart to heart, writing down as an aid to memory was an original necessity. What is a sacred transmission must be engraved on stone—on parchment in this case—like the Scriptures. The Gospel in its original sense of “announcement” made of various Gospel recitals (cf. Gal 2:2; Rom 2:16 etc.) is given this rank of Scripture, as is shown by the First Letter to Timothy, probably dating from the year 57 AD.

In fact, Paul quotes a saying of Jesus in parallel with a quotation from the Torah: “The Scripture says, You shall not muzzle the ox that treads out the grain [cf. Deut. 25:4; 24:15] and again, The worker is worthy of his wages” (1 Tim. 5:18). But the second quotation exists only in Mt 10:10 and Lk 10:7.

[There is a small difference as to what the worker is worthy of: in Mt 10:10 he is worthy of saybbārā/Greek trophe, “food;” while in Lk 10:7 he is worthy of ‘agreh/Greek misthos, “wages.” In Aramaic, the key word is the verb šâw’é, expressing the idea of “suitability” (rendered in Greek by axios, “worthy,” for want of a better word): “the worker is šâw’é (it is suitable for him, he deserves) his food” (Mt 10:10—commented translation of the Peshitta by Mgr Francis Alichoran). But in Greek, what one is worthy of should not be food but honor or a reward-wage (as in Mt 20); axios estin o ergastès tès trofès autou is obviously an Aramaicism that reveals a translation.]

In the eyes of a Jewish Christian in the year 57 AD, what text could have the authority of sacred Scripture, if not an aide-memoire, such as the Gospel according to Matthew which was then used (primarily) in the liturgy as had been the Torah?

Moreover, the conviction that the Gospels existed in written form well before the first “Jewish war” (66-70 AD) is not uncommon among exegetes working on Greek—the case of John being special, as this Gospel was composed in two stages. But few still perceive that the aide-memoire of public recitation in Aramaic is the source of the translations into Greek (and into other languages), directly or on the occasion of simultaneous translations written down—it is systematically in Aramaic that the Apostles and other witnesses of the Resurrection gave their testimony; which, if necessary, was translated into Greek or Latin by interpreters, e.g., Mark, for what Peter said. [“Paul had Titus as his translator-interpreter, just as blessed Peter had Mark whose gospel was composed, with Peter speaking and Mark writing down” (St. Jerome, P.L. 22, col 1002)].

It is possible that the first writings in Greek or Latin were private, since the people of these languages no longer had an oral culture (but a written one) and were less able to memorize than the Aramaic speakers. In any case, the need for official writings was felt early on, also because of the dispersion of the Jerusalem community around 37 AD, threatened by unrest, which set the liturgical tone for the other Christian communities: Matthew urgently needed to establish a reference document for the liturgy.

[The sources that place the Gospel of Matthew in Aramaic before the Gospel of Mark in Greek allow us to place the first one around 37-38 AD, by virtue of the famous passage in the third book of Against Heresies by Irenaeus of Lyon, where there is found the matter of the publication of Mark’s Gospel. This passage presents a difficulty, however, since it seems to say that the community of Rome was founded by Peter and Paul—this is inaccurate, since in 42 AD Peter founded this community alone—and since it already existed, Paul had no intention of going there, as he wrote in Romans 15:22. The most likely explanation is that the words “and Paul” were added by a Latin copyist in honor of the Roman feast of Saints Peter and Paul.

Here is the amended text: “Thus Matthew published among the Hebrews in their own language a written form of the gospel about the time when Peter [and Paul] was evangelizing Rome [until 42] and founding the Church there. After his departure [exodos, “departure,” which never means “death”], Mark, Peter’s translator, also transmitted to us in writing what Peter preached. Luke, Paul’s companion, also published the gospel while he was in Ephesus in Asia” (Irenaeus, Adv. Haer., III 1,1).

In order to date Mark late, some exegetes have attributed to the word exodos the meaning of “death,” so that the publication of Mark’s Gospel would be later than the martyrdoms of Peter and Paul, thus after 64 AD. But they are then in opposition to Eusebius of Caesarea who, quoting Clement of Alexandria († 215) and Papias († ±230), clearly indicates twice that Peter is alive at the time of the publication-translation into Greek: “They [Peter’s hearers] made all kinds of entreaties to Mark, the author of the gospel which has come down to us and Peter’s companion, that he would leave them a book as a memorial of the teaching given orally by the apostle, and they did not cease their entreaties until they had been granted… Peter … rejoiced at such zeal—he authorized the use of this book for reading in the churches. Clement reports this in his sixth Hypotyposis and the bishop of Hierapolis, Papias, confirms it with his own testimony” (Hist. Eccl. II,15 par. VI,14 6).]

The challenge of exegesis then is to rediscover the interplay of Aramaic orality, from the testimonies rigorously repeated by the witnesses themselves and then by their disciples from the 30s AD onwards. If there is a difficulty in discerning these narrative testimonies in our Gospels, it is because they are frequently intertwined. This is because of the very nature of the Gospels—they are organized for liturgical use, and therefore according to the Church calendar. They are lectionaries [Apart from exegetes working on Aramaic and aware of orality, some have nevertheless asked themselves the question of the synoptic Gospels as lectionaries, such as Gordon W. Lathrop, of the United Lutheran Seminary of Pennsylvania, in Après Jésus, l’invention du christianisme, p.160]—with the exception of John, which is organized for another purpose—The Gospel of John is organized according to oral patterns in a complex structure of meditation; it is not made for basic evangelization.

This major discovery, made possible by Aramaic oral studies, sheds light on the trial and error that began nearly four centuries ago and that leads each exegete working on the Greek to imagine his or her own plans for accounting for the Gospels—and no two agree. And of course, the idea that the Aramaic Christians of Asia (and of the eastern Roman Empire) lost their texts as a result of Tatian’s Diatessaron, and then had to re-translate them from Greek in the 5th century, with Bishop Raboula of Edessa, is a kind of academic myth—a convenient myth to avoid having to take a serious look at the Aramaic texts.

Proposition D

Proposition D seeks to clarify how the divinization of Jesus would have been invented—first by Paul and then by the Trinitarian definition of the Council of Nicaea (325 AD).

It does not matter that Trinitarian definitions had existed before. The problem is a misunderstanding of the so-called Christological discussions, which some scholars have believed to be about the divinity of Christ itself, when in fact they were about how to express it. It is true, on the other hand, that “Arianism” denied the divinity of Christ. But no Arian was invited to the Council of Nicaea, which met precisely against this denial.

At the time, Christian leaders were faced with the difficulty of agreeing on formulas of faith that would enable them to cope. The discussions at Nicaea and the subsequent councils were held in Greek and were marked by Byzantine ways of seeing and reasoning, which wanted to give conceptual definitions to everything. But sometimes this created more problems than it solved. Take the example of the Aramaic term qnoma, used by Jesus and found several times in the Aramaic New Testament: it was at the heart of certain divergences, because it corresponds neither to the Greek concept of ουσια (“nature”) nor to that of υποστασιϛ (“hypostasis”). The Council of Nicaea did not take sufficient account of the differences in culture and language, which eventually led, at the Council of Chalcedon (451 AD), to the exclusion of the non-Greek speaking apostolic churches, which would be called “pre-Chalcedonian.”

One can understand then the confusion caused by a certain number of inter-faith academics and by Islamologists. They believe that these sidelined churches (the Arameans of the Church of the East from now on designated under the sobriquet of “Nestorians,” and the Copts and the Armenians) defended Christologies comparable to those of groups opposed to the faith of the Apostles, that is to say, catalogued as heretics. And, in the past (and we can go back to medieval scholars), under the influence of Islamic legends, some even imagined that the Christology of Islam (which violently denies the divinity of Christ) was inspired by that of the Aramaic Church of the East—whereas, around 735, John of Damascus compared Islam with Arianism and in no way with the thinking of the Church of the East.

In fact, the idea was to link Islamic Christology at all costs to the Christological discussions of or after Nicaea, for lack of understanding but also for lack of serious research on the origins of Islam. We read until recently: “The Koran… belongs to a movement of Christians who remained pre-Nicene, i.e., churches or Christian communities that did not accept the dogma of the Trinity defined at the Council of Nicaea.” [In particular, it is the legend of the Nestorian monk Serge-Bahira who is said to have recognized the “prophet Muḥammad” while still a child and to have transmitted his Christology to him.]

In the end, only rather crude confusions seek to justify Islamic “Christology” by Christian theological debates; whereas Islam is rooted in a much earlier, post-Christian-Jewish phenomenon, which in fact goes back to the end of the Apostolic period.

It is true that a question, subtle for the historian, lies behind these confusions: what criterion can distinguish what is Christian from what is not? Is it adherence to definitions—but in what language? Before the definitions of the Councils, was there only a vast vagueness? Is belief adhering to definitions—assuming one understands something, which requires explanations that are not always clearer either? Or is it something else? In other words, are definitions fundamentally enlightening—which is what the Byzantines hoped for—or are they merely signposts?

If Christianity is primarily a life, it cannot be put into concepts and definitions. In the Gospels, in Greek, we read six times “Your faith has saved you,” or as in Mt 1:21: “he will save the people from their sins;” where the Aramaic means “Your faith has made you alive,” and Jesus gives life back to the people from their sins. Certainly, the Greek verb sozo has something to do with healing; but taken out of context, the statement “faith saves” could be understood in relation to a conceptual eternal salvation, or one disconnected from concrete life; whereas it is first of all a question of life (re)given here below by Jesus.

Therefore, if there is a criterion of Christianity, it can only be this: the Christian, whether Hebrew-Aramaic or from another cultural or linguistic area, is the one who believes that Jesus holds in Himself the power to vivify. Those who believe that Jesus is under the power of an Other, that is to say that He does not save by Himself but simply intervenes as a superman, or else believe that He is simply a model to be followed, that is to say that everyone must save himself by following this model, do not share the faith of the Apostles but another faith. They adhere to distortions of the Christian Revelation, whether they are of the first or the second type.

These distortions have generally been called heresies, thus creating an unclear catch-all (the Greek word ‘aïresis, which gave rise to “heresy,” simply means “opinion”). This vagueness does not facilitate the distinction between what is Christian and what is not, and often focuses attention on secondary aspects. What determines the Christian faith is that if Jesus saves by Himself, then the God revealed in the Old Testament is present in Him, for God alone can save-vivify. As for the way in which this presence is expressed, this is certainly already an object of the New Testament and will subsequently be the subject of many theological debates—but it is secondary. Unfortunately, these debates have often pitted different, but legitimate, cultural perceptions and expressions of the mystery of Christ against each other. In fact, all the apostolic Christian communities of the world today recognize each other fully and mutually in their faith, expressed in different languages (often not transposable from one to another—that is the difficulty).

Proposition D also leads one to call writings “Christian” that are not, either because they present Jesus as a messiah in whom God acts as an external mover or inspirer (according to the Arian-Messianist perspective), or because they present Him as a guide who, out of compassion, shows how to save oneself (such is the core of all Gnostic systems). Such writings are not Christian, and the groups who wrote them cannot be called “Christian”—nor can they be called “heterodox Jews;” they are in fact also in opposition to rabbinic Judaism (which repays them with the daily curse against the minim). This is why, instead of using the illegitimate term “Christian” for them, serious research leads to the qualification of these groups, which came after apostolic Christianity, as “post-Christians”—they exist historically and logically only in relation to the latter, from which they derive doctrines that would not otherwise stand by themselves.

The confusions linked to propositions A, B and C lead to those linked to proposition D, which is quite logical.

Proposition E

If faith in the divinity of Christ is a late invention, the Aramaic-speaking Christian communities must also be late, and they can only have existed in dependence on Greek Christianity, therefore not before the end of the third century—this is a logical necessity. It is said that they were only an outgrowth of this Greek Christianity in the Syriac East of the Roman Empire, or the result of the deportation of some Greco-Roman populations to the Parthian Empire.

This denial of apostolic antiquity of the Eastern Christians is expressed in numerous writings, for example by Françoise Briquel-Chatonnet, in her contribution to a book with the evocative title, Après Jésus: L’invention du christianisme (After Jesus: The Invention of Christianity). She speaks of a “staging” by Eastern Christians of a “conversion to Christianity” going back to the Apostle Thomas (p. 570). And in Paul-Hubert Poirier, one reads that “the expansion of Christianity” beyond the borders of the Empire dates from the 3rd century, with “the Christians beginning to use” Latin at the end of the 2nd century, Syriac at the beginning of the 3rd century only, Coptic at the end of the same century, Armenian in the 5th century, and other languages later still (p. 53). Did they not exist before? What is thus obscured is that from the first century until the great massacres by Tamerlane, Asia had more Christians than Europe. Of the twelve Apostles, only three (James, brother of John, Andrew and Peter) went West; the others went elsewhere, with the exception of James the Just, who remained in Jerusalem, considered the center of the world. To think that Christians existed only in the Roman Empire until the end of the third century is simply the result of a postulate; and this negationist postulate is fundamentally rooted in Proposition A.

Proposition F

Since the Syro-Aramaic churches are presumed to have existed only in the late period of time, their New Testament texts were therefore also presumed to have been translated from the already existing texts—i.e., from Greek.

But if the reverse is true, i.e., if early Christianity is no further West of Jerusalem (in the Greek Roman Empire) than East of it (in the Parthian Empire), it becomes essential to compare the best Greek and Syro-Aramaic manuscripts. And then, the Aramaic texts turn out to reflect a state of the text much earlier than the best Greek manuscripts, which appear to be the work of translators (various in fact and in various Greek dialects, which is the main reason for the existence of seven or eight irreconcilable families of Greek Biblical manuscripts). These Aramaic texts can shed light on most of the obscurities of the Greek or Latin texts, even if there is reason to believe that the translators did their best in the context that was theirs.

Proposition G

Since there were groups of Semitic language holding Jesus only as a man, one imagines that they preceded the churches of the same languages (Aramaic, Coptic); and that it was they who preserved the true Christianity of the Apostles (the Greek Christians having invented the divinity of Jesus). They are often referred to under the vague term of “Judeo-Christian sects,” or pre-Pauline or pre-Nicene groups. We have seen above how these labels are misleading. If Semitic or even other language groups speak of Jesus in opposition to the faith of the Apostles which is really known to us through the New Testament (which we can understand through the Aramaic texts even better than those in Greek or Latin), they are post-Christian groups.

The concept of “post-Christianity” was coined to designate the phenomenon of “leaving Christianity” that marked the 19th and 20th centuries, from the point of view of institutions (we also speak of “secularization”). But there is no reason to take into account only the institutional aspect. If we consider the theological aspect (or in other words, that of the Apostolic faith), we can and must look at the phenomenon that begins towards the end of the Apostolic era, that of groups of Judeo-Christians who questioned the faith they held from the Apostles, and who then organized themselves into groups and doctrines opposed to the Apostles (while keeping many traits of original Christianity).

These groups and doctrines, which would later be called “heresies,” are strictly speaking counterfeits (in the sense that a counterfeit is made to resemble the model, but it is no longer the original). These counterfeits, which constitute exactly post-Christianities, are fundamentally and historically of two types, corresponding to the two axes of Christianity (and thus to the two possible ways of counterfeiting it. See here):

Conclusion

The Propositions, from A to G, form a logical system. For this reason, it is enough that only one of these seven propositions turns out to be contrary to the data of serious research for the whole to be invalidated. There is no lack of reasons to question each of these propositions, starting with the first one, which is the most important—and which is even the key to the others. There has never been a “divinization” of Jesus, but rather a consideration of the plan of a God who revealed Himself in order to come and save humanity, which only He can do. The question remains open as to what God will do next, as a Second Coming of Christ is foretold. This is another question, which is not simple either, since Muslims also expect a second coming of Jesus, but it is not the same. It is understandable that some minds find all this very complicated and try to reduce their perception of Christianity to their logical and ideological schemes, from A to G.

It is therefore a new coherent and logical approach to Christian origins that must be promoted and explored, in accordance with Revelation and historical and anthropological data that are not censored or distorted by postulates. Such new orientations will not go without opposition—the seekers of truth are rare—but this is a characteristic of our time in almost all areas, alas.

Theologian and Islamologist, Father Edouard-Marie Gallez is the author of the magisterial Le messie et son prophète (The Messiah and His Prophet), published in Paris in 2005 (and awaiting an English translation), which is an 1100 -page study that reconnects the origins of Islam to factual history by showing that the Koran and Islamic legends developed gradually over time. This study paved the way of current research into early Islam. See Roots of Islam and the Great Secret. Father Gallez also participates in research groups on early Christianity and its influence.

Featured image: “Traditio Legis,” mosaic, Santa Costanza, Rome, 4th century AD.