According to recent economic data, the gap between the rich and the low-income people is bigger than ever before, and the level of inequality between Blacks and Whites is highest since 1989: “Whites have $13 for $1 held by African Americans” (The Washington Post on Dec. 3rd, 2014). The tone of the pronouncements is alarming, and, the claim goes, unless something is done, the wealth divide may become the cause of social unrest.

What goes unnoticed in the context of endless discussions concerning the growing income inequality is the galloping educational inequality where the blame cannot be assigned to the rich for the educational ills of the poor. In the economic realm one can tax the rich to transfer wealth to the poor, but one cannot transfer knowledge, that is, linguistic comprehension and social and scientific competence, of those who are highly literate to improve the comprehension of low-income children.

The last two hundred “democratic” years, which witnessed the spread of public libraries and learning institutions created for the use of ordinary citizens, abounds in examples of children from poor and modest backgrounds getting to the top of Western societies.

Twentieth-century — both in the democratic West and in the former Communist countries — demonstrates that one can elevate the uneducated masses to a historically unprecedented level of literacy and scientific competence. The key to success was teaching proper language – the language of educated classes (or elites – the word purged from American English) so that the masses of ordinary people could participate in High Culture and civic and scientific life of the country.

What we observe in Twenty-First-century America is an educational U-turn. We graduate masses of elementary, high-school and college students who are below the level of reading daily newspapers. Their comprehension is getting worse and worse each year, and the average present-day public-school student does not have enough vocabulary to read the same books that his counterpart did a decade let alone two decades ago.

We produce citizens who have no linguistic and thus conceptual skills to grasp the complex political, social, and economic problems that every nation faces in its history. The question is why? And if you think it is lack of resources or bad teachers, you are likely to be wrong.

Despite the recurrent media “witch-hunt” after bad teachers, teachers bear much less responsibility than one would like to assign to them. They are victims of cultural and institutional politics that pushed out the traditional methods of teaching and learning and replaced them by pedagogy, children’s psychology and, in the last decade, electronic insanity which makes children scroll through a text rather than read.

The last thing one sees is young people reading and what they read, if they read books at all, are books that bear semblance to literature, but they are not. They lack literary imagination characteristic of the Classics, the characters are psychologically flat, rarely animated by any virtues, and speak the language of the people from the street. Instead of making our children’s English better, more elegant, we perpetuate bad habits and cater to their existing vocabulary level, leaving them behind their richer counterparts.

If one wonders why foreign students, Asian, and many from former British colonies in Africa, are so successful in America, the answer is: they came from societies where educational habits did not change much for decades. Their parents brought with them traditional study skills and discipline – the two things which are absent here. Memorization and endless drills “till you get it right” are essential tools for getting high grades.

To some extent the same attitude still prevails in good private and most Catholic schools in the U.S. There vocabulary is still taught from serious vocabulary books in the old-fashioned way by memorization, drills, endless and relentless repetition and exercises. In some of those schools, students take Latin, French, sometimes German, which for an English speaker is the only way to learn grammar (since grammar is never taught).

As a nation, we need to realize that the wealth divide between “haves” and “have-nots” corresponds to “comprehends” and “comprehend-nots.” One cannot teach, for example, eighth grade science or history to students who operate on the fifth or sixth grade vocabulary level. If one’s comprehension is not up to the level of being accepted by a good college, one’s chances for social and financial advancement disappears from before one’s child’s eyes.

The educational abyss overlaps to a large extent with the financial abyss making America look like a “tale of two cities”: fewer and fewer well-educated rich and growing masses of semi-literate and helpless low-income people.

Unlike the acquisition of wealth which requires personal and rare qualities (industriousness, self-determination, etc.), all it takes to know one’s language well is reading good literature. Reading is what disappeared from American households and schools.

Few children from the poor backgrounds have heard of Charles Dickens, Jules Verne, Alexandre Dumas, Mark Twain, Hans Christian Anderson, the Brothers Grimm, Homer, Aesop, let alone Plutarch’s lives of great Greeks and Romans — the authors who formed the imagination and language of generations of readers in the Western world. Using a dictionary and reading Classics appears to belong to the remote past and is restricted to a relatively small group of richer children which makes them look like educational aristocracy.

Why do our youngsters not read the Classics? There are two answers to this question: Parents and younger teachers themselves did not read them, and the teachers succumbed to the ridiculous idea propagated by so-called “experts” in pedagogy that children understand literature best when they “can relate to” characters whose problems and language are theirs.

If so, how on earth can one explain how millions of girls of several generations ago could relate to Hans Christian Anderson’s “The Princess and the Pea” without sleeping on a pile of pillows, or Snow White? The answer is, we relate through imagination which is a vehicle to a more beautiful world and a way of getting out from the ugliness of our own environment and poverty.

No literary character is real. Literary characters are merely plausible, and literature is a promise that we can imagine being elsewhere in life. To illustrate my point, let me invoke an example of a poor Hispanic Brooklyn girl who became America’s Supreme Court Justice – Sonya Sotomayor. This is what she said in the January 13, 2014, NPR Fresh Air interview:

“One day talking to my first-year roommate … I was telling her about how out of place I felt at Princeton, how I didn’t connect with many of the experiences that some of my classmates were describing, and she said to me, “You’re like Alice in Wonderland.”

I said, “Who is Alice?”

And she said, “You don’t know about Alice?”

I said, “No, I don’t.”

And she said, “It’s one of the greatest book classics in English literature. You should read it.”

“I recognized at that moment that there were likely to be many other children’s classics that I had not read. … Before I went home that summer, I asked her to give me a list of some of the books she thought were children’s classics and she gave me a long list and I spent the summer reading them. That was perhaps the starkest moment of my understanding that there was a world I had missed, of things that I didn’t know anything about.”

Justice Sotomayor’s words should be a cautionary tale for all present-day educators who by experimenting with new methods are in fact closing the door to the future before our children’s eyes.

How did we reach such low level of literacy? There are several reasons, of which the first one is the idea of multiculturalism propagated in the 1980s and 90s. According to it, a multicultural society should, or even must, represent minorities in educational curriculum.

This argument is similar in nature to the one I presented above: it is based on the false intellectual and moral premise that the work of art does not have an intrinsic value; its value lies in the fact that it was created by a member of a given minority, and the minority reader (or viewer of a painting or sculpture) is more likely to appreciate it if he is of the same sex, race, ethnicity.

But to make such a claim is tantamount to saying that there are no objective criteria of judgement. The criteria are subjective and determined by race or sex or ethnicity.

Secondly, multiculturalism is inimical to the idea of a nation. Americans may not be a nation in the same sense in which other nations are, and whose literature captures peculiar moments of a historical development, mentality and the features of its people.

It is unimaginable to be a German without knowing Goethe, Schiller, or Heine; French without knowing Racine, Corneille, or Moliere, Pascal and Descartes; Russian without knowing Pushkin, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Lermontov, or Gogol and Pasternak. They are not just great writers; they are national monuments, of which Germans, French, and Russians are proud.

To be sure, America does not have national literature in the same sense. Knowing Thoreau or Emerson, Steinbeck or Faulkner, or C.S. Lewis does not make an American American. What does is the tacit intellectual commitment – inculcated in the educational process — to principles on which this country was founded, and which for a century or so was transmitted through what Americans used to call “Great Books.”

There are no American writers in it. What the American “Library of Alexandria” contains are the greatest treasures of European intellectual tradition which goes back to the Greeks, Romans, great Christian writers, such as, St. Augustine, St. Thomas, Calvin, Luther, and others. But first of all, much of what one finds in this library is British or English, including the greatest works in the English language: the language of America and the language of its legal and political tradition.

As things stand, America appears to be in the final stage of repudiating its threefold past: British, Protestant and Western. Multiculturalism is not merely a failed promise of a providing a better education; it is a moral and intellectual disease, and that is how we should treat it. We need to repudiate it loudly by returning to our old “Library of Alexandria.”

Pouring more money into education will not solve the problem and will more likely make things worse. The money will be spent on organizing conferences on new methods of teaching, relating to students, buying new computers – all that is taking students away from reading. It is time to recognize the simple truth that there are no new methods in education but one: old-fashioned painstaking acquisition of vocabulary, learning grammar and reading good books.

It may not always be true that every rich person is educated but the majority of children from richer families or families where reading is a daily bread are the same who will graduate from top universities. They will acquire wealth while the semi-literate will remain financially poor because they will not be able to master subjects necessary to get jobs to get out of poverty and advance their social status.

There is also a place for the billionaires and richer members of our society to help the poor, not by squandering money on educational foundations, but by directly engaging in doing something: sponsoring children Classics book-clubs, giving incentives to children who read a lot, organizing serious foreign language classes where they could learn language and grammar.

Perhaps McDonalds and other food chains, which live off the low-income people, could promote Classics by putting books, like Starbucks does selling CDs with music, at the counter offering “voracious readers” awards, or giving a free meal to children who read X number of books. Education does not have to cost a lot, provided one knows what it is, but social costs of having millions of poorly educated citizens can and we should do something about it.

If we are serious about improving education, we need to go back to basics: a pencil, a sheet of paper, a dictionary, basic Latin and Greek, and classic literature with a teacher who should not be bothered by a continuous nonsense of improving methods of teaching. No method is a substitute for literary competence and imagination.

Zbigniew Janowski is the author of Cartesian Theodicy: Descartes’ Quest for Certitude, Index Augustino-Cartesian, Agamemnon’s Tomb: Polish Oresteia (with Catherine O’Neil), How To Read Descartes’ Meditations. He also is the editor of Leszek Kolakowski’s My Correct Views on Everything, The Two Eyes of Spinoza and Other Essays on Philosophers, John Stuart Mill: On Democracy, Freedom and Government & Other Selected Writings. He is currently working on a collection of articles: Homo Americanus: Rise of Democratic Totalitarianism in America.

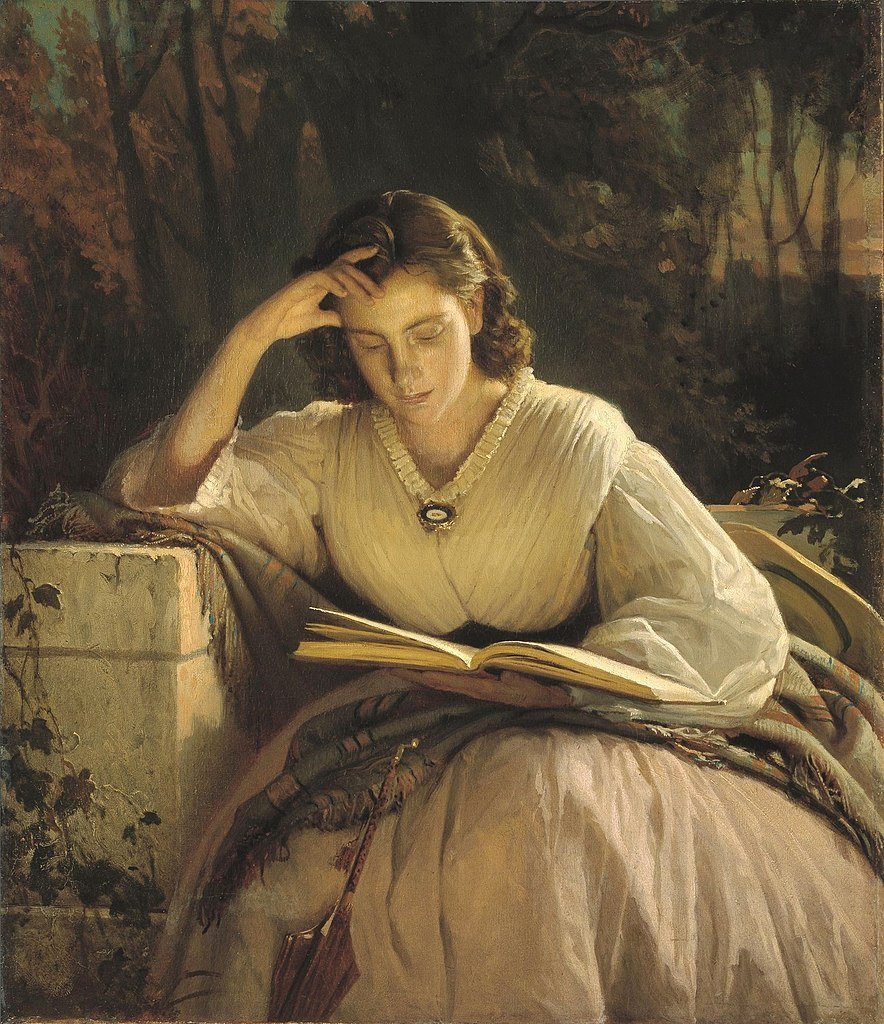

The image shows, “Woman Reading. Portrait of Sofia Kramskaya,” by Ivan Kramskoi, and painted sometime after 1866.