These thoughts were first delivered as an oration, the Third Stuart Saunders Memorial Lecture, given at the Auditorium of the Neuroscience Institute of the University of Cape Town, on May 22, 2023. This written version is considerably different.

“Lasciate ogni Speranza voi ch’ entrate,” said a placard outside the senior common room. A doctoral student must have posted it, in propitiation of a desired but improbable job given the “financial constraints,” I thought. I sat down and let my mind wander and wonder. What did that future jurist, or perhaps lawyer, mean? Why this gesture, this interpellation, this sorrow even? A moral claim, in any event. An occasion to reflect on scholarship?

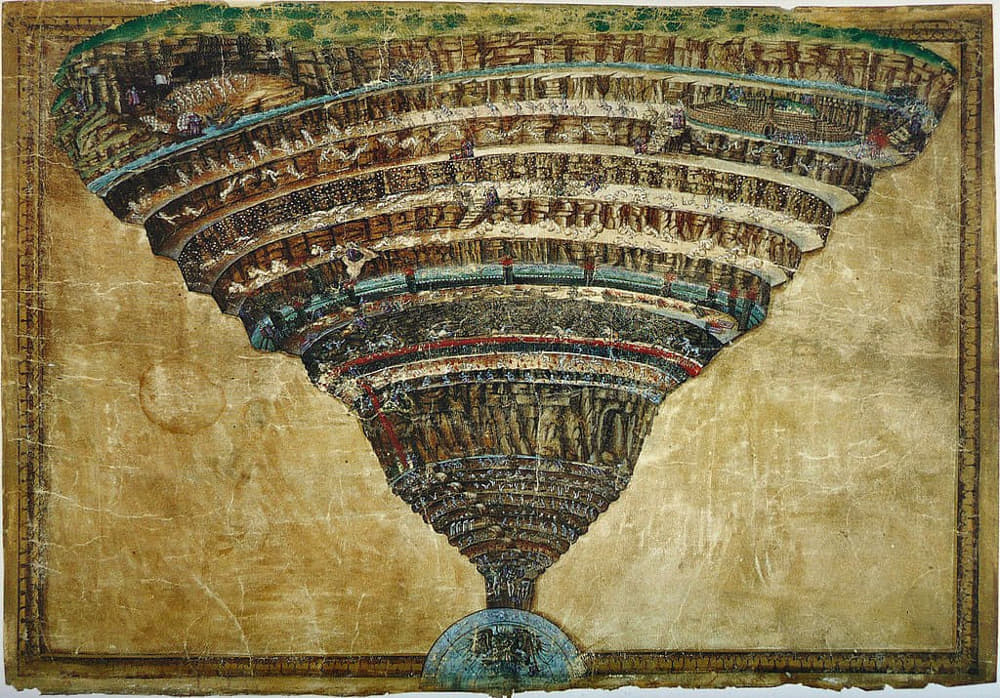

In an age of universities and academics “ratings,” of Nespresso conferences offering quick and easy 15-minute presentations, and the vulgar business of journals held, in firm accountants’ hands, by international publishing groups, “sovereign” funds in disguise, in short a Hell university managers (and Presidents or Vice-Chancellors), refuse to consider, I took the grad student’s caveat literally, and I stepped forward, as it were, walking behind Dante, and Virgil.

This is no stroll up to the illuminating Ideas of the Table of Cebes, but a slow progress into the phantoms that inhabit scholarship’s morality. Mine is a tropological reading of Dante’s Inferno applied to the negative ethics of scholarship. It is not exhaustive. It is a rhetorical exercise in the very best sense of the word, clearing stuff that encumbers reason and argument—let us remember how at the very beginning of Rhetoric Aristotle calls for getting rid of rubbish, and opening a straight path. In this case, Iet us try and clear the rubbish indeed that stands in the way, the hodos, of a scholar’s progress.

Let us follow Dante.

1

In the first circle, Dante meets, in particular, ancient philosophers, Greek thinkers, such as Plato and Aristotle.

Why are scholars of ancient Greece, the source of all scholarly knowledge at the time, from physics to medicine, morals to logic? Why are they in Hell, and why at its most benign level? Reason is that they have perceived the truth of what it is to be a human being, be it in metaphysics or in physics, in ethics or in formal and informal reasoning. But they lacked a true concept of it.

Their scholarly endeavours lacked something fundamental. What French thought-libertines, such as La Mothe le Vayer called, with a bold oxymoron, “la Sagesse des Païens.” Wise, sage, indeed, but lacking a knowledge of divine truth, despite the aletheia-Revelation. Those words “wise, sage” were a trope for “knowing,” and to deny them the status of “doctors of the faith” which, undoubtedly, had they contemplated the Word made Flesh, and acceded to “knowledge” they would have earned (such was the tale which spared the French sceptics a dire fate).

However, ancient philosophy itself made a clear distinction between “knowing” and “knowledge,” aistheta kai noeta, to put it differently: “percepts” and “concepts.”

The wise ancients perceived a connection between human understanding and the human condition, but they lacked a concept of that relationship between what a human being can achieve, in a scholar’s case intellectually, and the purpose of the universe within which scholarly enterprise fits, which for Dante was its placement within a superior divine order. In this case, ancient scholars had a percept of the ultimate goal of scholarship, they did not have a true concept of it, that is of the truth of Nature. We know that the position of science regarding a divine scheme of Nature still rages on today.

A tropological, and moral, translation with regard to a scholar’s enterprise ensues: to be clever as a scientist or perceptive as a philosopher, to be intelligent and enterprising as a scholar, that is to follow the ways and uses of a given scholarly community, its properly named ethos, yet without a firm concept of truth, is advantageous, but fraudulent.

Often scholars stay there, and quite happily. They go through the moves, but remain at the level of percepts—cleverly constructed, persuasively presented as concepts, forcefully argued, but percepts, aistheta, none the less.

For instance, the so-called “robust” debates on climate change, the nasty controversies about the warring situation in Eastern Europe, and the opposing arguments about Covid, rest, among scholars (I am not talking here about the public), on a constant game between percepts and concepts, opinions presented by scholars as veracity, and established facts or arguments logically valid as well as exact.

When scholars behave like the public who is naturally swimming in the amniotic liquid of percepts, they fail being scholars.

I have tried that notion on some of my brighter graduates. They see the point, but they do not see what to do about it, and with it—as scholars. They often prefer to fall back on percepts. Many are “wise,” smart, perceptive, and that suffices to sustain an academic or professionally “learned” career. Scholars they are not.

2

In the second circle of Hell, Dante meets those who lead lives driven by passionate love. Love, human love, is supposed to be what people, especially in the Western mindset, are made to believe as being a superior feeling. Some cultures do without it and are none for the worse. Roland Barthes, a critic unorderly decried today, wrote A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments to debunk the narrative of human love—as just a narrative. By contrast, he had read Loyola closely, when the Jesuit saint’s Spiritual Exercises were a terra incognita to secular critics (but oddly he gets no credit for it). He had a clear idea that “love,” dispassionate, is a travail of the mind, an active arming of the mind, as the word exercitium says, and Barthes knew his Latin (and his Greek).

But how does “love” relate to scholarship?

Again, tropology: scholars are not supposed to fall in love with ideas, theirs or others’. They are not supposed to be in love with what they think. They must maintain a distance. Getting infatuated with a topic, a research theme, an author, an idea, is dangerous. One gets ensnared by the self-loving turns of a narrative about one’s own mind. Some of us get caught in the loving knots of libido sciendi.

Why? It has to do with fetishism.

There is often a fetishist approach to a scholar’s endeavours, just like love is in essence fetishist.

Now, what is a fetish? A fetish is a strategy of replacement. In it most serious form, someone who is deeply mentally disturbed will hallucinate that an object, any object, is reality; reality meaning the subject of desire—“love.” An object replaces a subject.

Benign example: Buying an expensive perfume or getting into debt for an expensive car are fetishist acts: you replace the lifestyle you cannot afford with a fetish of that lifestyle. You fulfil your desire, and hallucinate that which you cannot have (worse, is denied to you, and in full display—cruelly, hence feeding the narrative of endless dis-satisfaction).

In intellectual matters the desire, the passionate love for fetishes is a very strong “drive,” especially among younger scholars. “Drive” is correct, but placed here in-between inverted commas, because those who use it all the time are evidently ignorant of its true meaning: it is the Trieb of psychoanalysis—Eros and Thanatos at work. It coheres.

It is indeed a natural bend, exacerbated by the demands for “teamwork,” “collaborative research,” and the like. But it leads to repetitive research. One cannot let go and move on. One has found one’s object of desire, and one wants to stay with it. You can call it silo thinking if you wish. In reality, it is a fetish. Roland Barthes, him again, warned his students: do not fetishize your dissertation into a book.

That sort of fetishist behaviour is often encouraged by funding agencies and managers: many, not all, want to see how a scholar has a trajectory, follows a path, undertakes a “journey” even as some say, having read that book by Coelho, and, nail in the coffin of noeta: a track record. Funding outfits often look at deviations from the course as proof of a lack of focus. Of course, they would, since they think along managerial lines—and their own fetish.

What is their fetish?

The magic bullet of Management: POLC, plan, organize, lead, control. With it the panacea of “lean management,” where things have “got to” move fast and in one direction, and “produce” “deliverables.” Ideas do not “move fast.” When you hear “productive” about a scholar, hear the alarm bell ring. It is a red flag for managerial fetish. Thanatos, that fundamental Trieb, reigns.

That sort of intrusion in the life of scholars produces a poorer intellectual life indeed. Which does not mean a poorer academic life. Both lives need not coincide. It is an error to envision that colleges and universities are places for scholarship. They may be places of scholarship, where some scholars can follow their path. But they are not places for scholars. That is no longer their teleology, their final cause. Universities may be the efficient cause of scholarship, but it mostly is no more that—“efficient” is a concept naturally adopted by the managerial university.

3

The third circle is about gluttons. That is, figuratively, about those who instead of being satisfied with meeting basic, bodily, needs, always want more.

In other words, their body has replaced their life. They are not human beings but recipients for other bodies, meat, vegetables, fruits, drinks. They eat animal and vegetal life in order to augment their own bodily life. I often wondered if the disgust strong-minded vegans feel toward meat-eaters, does not come from the carnivorous image of bodies eating bodies.

What about scholars? When I read verses from Canto VI, and I look for a tropological meaning, I am reminded of the expression: body text. And then I think of bloated footnotes in research papers, or one word followed by a bracketed string of So-and-So, page such-and-such, sometimes running for an entire line.

A gluttony of so-called references. Swelling the body of an article with others’ scholarship without, usually, any sort of pointed, coherent explanation between this word, hopefully concept, referenced and that kebab of data on a skewer. One feeds on anything that comes close and within grasp.

Others’ ideas and “body of work” do not exist to merely being gorged on, and regurgitated, often half-digested.

It is an illness most perceptible in the social sciences, in their strained effort to pass for “sciences,” less in the pure humanities whose scholars still see themselves members of a club, the Republic of Letters; but scientific papers are far from exempt from a rhetoric of agglutination and precedence to tick the boxes of credits parsed down to the least intelligent lab gesture by X (fifth “author”).

There is also little value in demanding from students, in their apprentice-ship of scholarship, to chew on so-called literature reviews and methodology parading. What is the actual value of filling up two compulsory chapters of a dissertation with those pre-emptive strikes? Or inane preliminaries, in academic articles, reciting a litany of saints of a particular faith as a preamble to get on with the job? Yes, we know what Agamben said about emergency; spare us triteness, show us what you do with it. What I want to see at work, in the body of an analysis, is how sources are activated in the course of a dissertation, or a paper, how a methodology is put into action.

To refer to them is not a scholarly gesture.

To infer from them, is a scholarly gesture.

4

In Hell 4 Dante casts the misers and the spend-all.

First, why are they stuck together in Hell 4? Because, possibly, they are a living hell to one another, as in a Balzac’s novel.

Figuratively both are the two sides of the same delusion: either they indulge in material goods by accumulating them, in order not to share them. Or they indulge in throwing away everything without any regard to the value of each item, which is a way of not sharing, as sharing has to be discriminate in order to fit the purpose of generosity.

A tropological reading sheds yet another light on the threats to scholarship.

How does a scholar hoard? What is a miser-scholar, if I can coin that word?

A hoarder scholar indulges in never deviating from his, her primary hoarding, be it a doctoral dissertation or a book. Everything always goes back to it. Niches can be comfortable, but if you are alone in it, what is the value of being so specialized? You stay in your dog-pen (“niche”), chewing on your bone.

By contrast, the reverse indulgence is forever turning yourself into an open house, having an open table, laying out whatever you have developed in terms of ideas, percepts often, to everyone. Large conferences, select colloquia, new associations that spring up all the time—made worse since the virus emergency—workshops on this and that, training about x, y z, compounded now by the invasive remote attendance, are all perfect avenues for academic spendthrifts.

I have seen intelligent colleagues, smart and astute, erudite even, cast to the winds whatever they have achieved, just for the sake of being present at, being heard at, publishing in. Relentlessly.

Clearly, spending or hoarding has to do with value—whether you hoard or you give away by largesse, you do so because you believe (percept…) it is valuable.

To go one step further: in scholarship there is worth, and there is value.

A scholar may have great worth, and lesser value.

The difference between the two is the following: worth is intrinsic. It resides within the field and discipline in which the scholar creates ideas. Value is extrinsic. It is assigned from outside the field and discipline.

Worth? I remember a colleague who never wrote a single monograph. He/she wrote short notices in small journals independent from the publishing industry. She/he never thought it necessary to share beyond a small circle of like-minded scholars, nor to assemble notes in a book, not even in that ersatz of the academic economy: the edited volume. That colleague placed no value in doing it, but knew her/his worth. So did friends.

Value? Clearly the prevailing ideology recoils at the worthy scholar. The industrialisation of academia discourages such scholarship. But scholars must have value for their institution as the vast majority of them usually belong to academia. Value is then assigned by outside processes—you know what they are: deans’ reports, funding agencies fantasies, internationally accredited “goals,” “visions” so-and-so, fabricated by overarching institutions. These are neither bad nor good; they are processes that reflect a current state of affairs in a managerial society. It is a fact. However, bending to extraneous facts uncritically is not what a scholar does.

Time lo leave Hell 4.

5

Secure in their frail skiff, Dante and Virgil now float on a stream of slime, and overboard they look at a slurry and at… the Dissatisfied.

A river of slime is a powerful image for those who see time and life pass them by, flow by irremediably, irretrievably, and fall into a deep dissatisfaction as they would do into sludge.

Being dissatisfied, especially when you are employed by a university, is quite common.

Among academics, dissatisfaction ranges from annoyance, to despondency, from hatred to self-hatred, from disdainful retreat to bilious withdrawal. In the classical theory of emotions, all these “passions” fall under one umbrella: anger.

It is one the strangest features of scholarly life in academia: a tendency to be fiercely angry, which befits sanguine characters, or to be bitterly morose, which befits more reserved ones. Aristotle, in his Rhetoric, which contains the first fully-fledged systematic theory of emotions and how they impact social life and are turned into public arguments, anger is the key emotion: anger surges forth when a feeling, a knowing (a percept) or a knowledge (a concept) of injustice, takes over.

For classical thought, anger is the driving force of politics, from subdued dissatisfaction to open rebellion, but it is always caused by a belief that an injustice has been done. The dissatisfied usually believe they have been treated unfairly. Academics do, as a rule.

The paradox is that, being intellectuals, scholars have all the means at their disposal to reflect on and analyze their own dissatisfaction. That is, to move beyond opinion to fact and argument. After all they spend their lives weighing hypotheses, testing results, refining conclusions. Their lives are immersed not in a slurry of bad ideas, but bathed in the clear waters of reason.

Presumably.

And yet a scholar, mildly or strongly dissatisfied, will channel one’s sense of injustice and dissatisfaction rarely along lines of reason, but along lines of opinion, mostly ideological lines.

Often a dissatisfied scholar will turn a personal grievance into an intellectual battle, will rally forces as must be necessary to show that it is not a personal grievance at root, but a case valid for a group.

Dissatisfaction and anger do produce results, in terms of power; it is doubtful they produce scholarship. It can pass for it. It rarely is.

Ideology is alienation as Marxist philosophy teaches us. An ideological scholar is alienated, on top of being angry.

Conversely a scholar who inflicts onto oneself the self-injury of withdrawing from confrontation, and turns anger inwards, becomes melancholiac. In the Renaissance it was deemed that melancholy was the right composure for a scholar. A scholar was supposed to brood over matters of the mind. Hence needs to retreat from too much intercourse, too much company, too many distractions. It is a pleasant melancholy; it is not dark, but the soft penumbra under the foliage of a grove-like retreat.

The irony of that fantasy could not be lost on Dante who wrote his masterpieces while being thrown out of his city, hounded, condemned to death and threatened to be burnt at the stake. He, a scholar, did not write in anger or melancholy—but in the quietening of fear.

He retreated.

Retreat is an idea which during a good millennium was central to the intellectual enterprise, and no longer is: it was called skhole. In the classical world, and that of Dante’s, a scholar lives in, and lives, skhole. The word “scholar” echoes it but it is a pale ectoplasm of the original concept. In the classical world skhole meant leisure, otium in Latin. The Augustinian tradition would call it, for its own ends of course, vita contemplativa. The application differs, but the concept is the same: skhole.

Leisure to what end? To provide a scholar with time and quiet to think without the pressures of negotium, life outside, social engagement, and working.

“School,” the word, copies skhole the idea, and indeed schools should provide the quiet time necessary to learn, without negotium interference. Children who attend school also should think about enslaved children who work in factories: they work, they don’t go to school.

Indeed skhole, peace and quiet to read and think, has always entertained a complex relationship with work. Real work. Backbreaking work.

It is interesting that in the 1950s a French socialist, Joffre Dumazedier, invented a new sociological notion which revived, in contraposition to working, the antique practice of skhole, with a new twist: “society of leisure.”

More than an idea it was an intellectual activism at the service of those who, actually, work: training and methods were set up and implemented to give workers “leisure,” time and space, that is skhole, in order to cultivate their minds, to learn how to argue and analyse; that is: how to reflect knowingly (noeta) on why being exploited made them so angry, or dissatisfied, and thus turn instinctive “knowing” (about the workers’ conditions) into an actual knowledge. The “society of leisure” was a form of scholarship. Leisure society was the humanist response to class struggle. A new skhole, to sum.

No longer today. Today “leisure” is quite the opposite: it is fabricated with consumer goods, in order to prevent workers from having time to think about their conditions, and make them hallucinate fetishes of the Good Life through more consumption. They are not afforded skhole but merchandise to be distracted from their condition, and from thinking, and to allow their masters to extract more work out of them.

Thus, when a scholar, who belongs to an institution, is dissatisfied, the first question to ask is: are you angry because you are a worker? Are you a worker? How do you define work? How do you retreat into leisure?

6

Dante and Virgil are now standing at the gates of the City of Hell.

In bolgia 6 are relegated heretics, religious dissenters, and partisans, political fanatics.

I am setting aside the religious aspect, but I retain Dante’s figurative intent: what to make of a scholar who holds partisan views within the scholarly enterprise? Not outside of it, as an individual engaged in society—many are not bothered, and often are not cleverer than the average citizen when it comes to politics—but what of those who, inside scholarly endeavours, activate partisanship as a part of, or even a drive for, their scholarship?

In intellectual intercourse scholars encounter, inside and outside academia, other intellectuals who are entirely devoted to defend a cause. That cause can be anything, but its function, when activated, is to override everything else.

Scholarship is then an expanding of personal prejudices, of firmly held percepts. Scholarship is put at the service of a set of opinions, a set of feelings, a set of values: it becomes secondary to reason. It is domesticated to serve a potent master that often suffers no contradiction.

Yet it is a choice. Or “heresy”: “heresy” is a not specifically religious, it means choice.

In matters of belief, it refers to an intellectual choice. Theologians called a heresy a “sententia humana,” a human statement—departing from the logos of the Scriptures. Today, outside the Christian frame, we could call a heresy a “personal choice.”

Scholars who allow themselves to push forward their “choice” of opinions, about politics mostly, over truth, have chosen a set of beliefs, percepts, as guidance for their erudite work. They have chosen to cast their scholarship into the mould, the chosen mould, of a knowing, not a knowledge.

They become partisans within their own fields of intellectual enquiry.

Some fields of enquiry are more fertile than others in allowing partisan choice to take over rational enquiry. Scholarship then often takes the public, publicized, claimed form of dissenting, in order to push forward the choice that drives it, and helps pass partisan opinion for reasoned scholarship. Grandstanding ensues. Intellectual “heresy” and partisanship are presented as more dignified, more important, more ethical, more useful to society than the prevalent scholarship. They claim the moral high ground. Some scholars build careers on their sententia humana—a personal choice driven like a nail into scholarship, and driving it.

However, those who really are in danger are young scholars.

For young scholars to declare upfront, “I believe that… I am passionate about” gives them an emotional drive, of course. But is it a scholarly approach?

When my MA or PhD students embark on a dissertation, and I have supervised for 40 years now, I always warn them: never begin your analysis by knowing what you want to prove. Do not have a conclusive opinion on the matter. Let the evidence lead you to what is the rightful, truthful conclusion. Never discard what goes against what you believe.

You may not like it, as it may not fit your belief, but then you have three choices.

First, you can review all the evidence and then lay it out in such a way that it will give you the result you wish, in line with your belief. You will side-line all that disproves your belief. What you will then perform is not scholarship, but an act of advocacy. It requires agility to do so.

As for me, I will be observing how smartly you do it, and possibly I will evaluate you on that skill, regardless of the veracity of the outcome. Nobel laureate in physics, Richard Feynman, famously called it “cargo cult science,” when he indicted funder-satisfying research. Long before Latour, he had, as a scientist, uncovered the inherent “rhetoric” of industrial, politically driven research: an exercise in advocacy, and in epideixis (orating on the “virtues” of an extraneous factor, be it political or industrial).

Or, second, you may not engage in that sort of selective work, and do a proper scholarly work. Confronted with an outcome that goes against your belief, you will ask yourself a moral question. That question will not be about the truth of the protocols you followed, since you have decided not to engage in cargo cult science, nor in epideixis (playing up to what funders want, in fawning obedience).

No, the question will be a moral question you will have to ask yourself: why was my initial belief so wrong? Yes, I was wrong but why did I believe in it? It takes courage to admit error in perceptions of reality, especially social, political. That is what a true scholar does.

But, third, if you lack that ethical courage—which can also be a professional safety mechanism in a hostile environment—then you have a third choice, a choice of pure partisanship: you retreat from rational scholarship back into belief, and say, well, yes, that is the correct outcome, but I don’t like it. It does not suit me. Very few have the perversity to do that in full awareness of the fact they are doing it. But it happens. And it is a violence against reason.

In short, in Circle 6, inside the City of Hell, Dante allows us to reflect on intellectual violence.

Which leads Dante to confront other forms of violence—against human nature.

7

Hell 7 is, indeed, the dwelling of the truly violent ones. Of perpetrators of violence against human nature, immersed in a river of boiling blood. Their crimes are not what we would today, in democratic societies, call violent crimes, such as rape. These crimes against nature are quite unique. And loaded with tropological meaning with regard to scholarship.

Dante speaks of the fraudsters, the corrupt, the suicides, the blasphemers and—the bankers.

Let us look at the apex of crimes laid out by Dante, leaving aside the fraudsters: suicide, blasphemy, lending money at profit.

What is the logic behind that sequence, not immediately obvious to our flat, linear way of reasoning? Tropologically, it tells a different story. Dante’s argument is about violence against human nature, and it is connected to the idea of giving.

Suicide? Today suicide has become a societal issue: bullied teenagers, workers harassed by managers, and also terminal patients, euthanasia.

Whatever the euphemism: to kill oneself or let oneself being killed is suicide.

In Dante’s time, suicide was an eminent crime, and for two reasons: first it is murder; second it is murder of the gift of life. In the Christian tradition, suicide is not laudable and honourable, and legal, as it was in ancient Greece and Roman stoicism, or still today in Shinto, but it is the violent, criminal refusal of the gift of life. This unique gift does not belong to the human individual, but to God alone.

Now, how does a scholar commit scholarly suicide? Or, to rephrase it, how does a scholar reject the gift of scholarship? It is a tough one, I admit, to read tropologically. Let us set it aside for now. But let us store the idea of gift.

Blasphemy? All major religions, of the Book or not, have some interdict against insulting the divine. That is, nature itself. The human shall not insult what is above human condition. The creature shall not insult the Creator. Still today in many societies that are, or close to being, theocratic, insulting God is a crime punished by death.

The reason why, in the religions of the Book, blasphemy is a violent crime issues from the fact God cannot retort in words: God cannot speak back; the one who utters a blasphemy arrogates language. Saint Augustine called it “operatio per linguam” (De Moribus manicheorum II, 10, 19).

That is why, already in Leviticus (24.16), the law, human law, responds in lieu of the divinity, by imposing legal sanctions. It is for human law to punish that crime against nature, blasphemy, as God is nature itself.

You will find the same network of ideas regarding “save the planet,” whereby daring to query “nature” as portrayed by “climate change-apologists,” is cast as a blasphemy against Nature—Nature that cannot speak back, hence needs human surrogates and legal rejoinders.

Where is the gift? In a religious vision of nature, God has given humanity the gift of speech, unique among living creatures, a gift now turned against the giver, God. A gift defiled.

Usury, money-lending at interest? Against nature?

That complex argument occupied scholars for some six centuries in Europe, in the distant wake of Roman jurisprudence on mutuum (loan), mediated by Christian theological interpretations, and may be boldly summed up as follows: the lender of money uses money as a measure to decide on interest rates, hence commits a moral fault. What is moral is charity. Natural justice wants you to give, not to lend at profit. Lending money at interest or expecting a refund is immoral. Charity is immeasurable.

Let us keep in stock the idea of a moral fault; that is a crime of violence against natural law, here charity—and again the idea of giving.

To sum we have, reading Hell 7, three crimes against Nature; all three bound to the idea of the gift. How does it relate to scholarship?

Suicide? For a scholar, suicide is not to realize that scholarly activity is bound by and to the “nature” in which a scholar lives, as we say without thinking seriously about what it implies: a natural environment.

If you are a scholar at a university, the university is your natural environment. It does not mean you agree, in private, with its diktats and arbitrary fancies; it means that you have fully understood what that “nature” requires of you.

Some institutions used to, some still do, require adherence to a set of explicit values, faith or ideologically based. That is their nature, and like in Dante’s world, the scholar who does not comply is perceived as committing a grave injustice, a moral fault, of violence against the nature for the university, refusing the gift of belonging to it.

The situation is perverse when the nature of the institution is not declared contractually: often, universities speak of their “values,” of their “vision,” of their “goals,” yet without having themselves (and their communication office) a clear idea of what it entails and what these words mean. In fact, they are creating a nature against which scholars can be held accountable for blasphemy, and may be led to commit, figuratively, suicide.

But what about usury, the third crime against nature? To recall the argument that it is the opposite of giving: Scholarship is in essence charitable. It is a gift. Some academics are scholars, many are not. And that is fine. It is part of the division of labour that makes up an academic workforce. But the gift of scholarship is generosity: sharing without expecting a return, a profit; and conversely accepting gracefully to be given knowledge.

There are two factors at play here: freedom and value.

Concerning a scholar’s freedom, a true scholar must retain the right to choose with whom scholarship should be shared, and thus be able to share it freely, and not under duress of “protocols” and what not. In order to make sharing it a real gift, an act of free choice. Giving under rules of obligation, thus for non-scholarly reasons, is not giving. It is not caritas. It is an economic transaction to satisfy “stake holders.”

Current college ideology is to push for Open Source, and indiscriminate sharing of research “products.” I suggest that it is not such a good scholarly practice. Scholarship requires to be selective. A scholar’s freedom is not to share everything with all and sundry, or with “partners” imposed by outside protocols; that is a false freedom. It is a usurpation.

A scholar’s freedom, that is to exercise one own’s freedom as a scholar, is to decide who is worthy of being given the fruits of scholarship. The Republic of Letters of pre-modern Europe was not a network of free loaders: it was a consciously aware and careful exchange of ideas. The current, and often fraudulent “peer-review” nonsense is a mendacious copy of the true peerage of scholars of the defunct respublica literaria.

This inane, and innate now, percept of “sharing” scholarship is perilous.

At a banal level, we know how the Internet can translate complex scholarly arguments into political propaganda, concepts into percepts, veracity into partisan opinions. My mentor in rhetoric, Marc Fumaroli, used to say, scholarship rests on “des têtes d’épingle” (on pinheads), meaning: it is hard to share ideas with those who do not wish to understand minute nuances, which make “all the difference,” and prefer to believe in brushstroke “knowing.” Popularized knowledge cannot care about decisive, often imperceptible, nuances, the media hardly, the Web2.0, that agglutinative mess, never.

That alone should guard us against placing scholarly knowledge within the reach of anyone and everyone.

At a deeper level, the Open Source managerial ideology, as it is one, is based on a fallacy regarding the rewards of scholarship for the natural environment in which a scholar operates.

Here is how: universities expect returns from sharing all scholarship. When I say “expect,” I do not imply any explicit strategy but, as all ideologies, it is an internalized mindset hardly ever brought out into full light. That expectation is based on the capitalist notion of value.

Or rather, surplus value.

Scholars create surplus value, that is wealth in excess of the work they perform, and the costs attached to it. Some colleges use the “cost of employment” method of calculation in order to avoid measuring value. This is why academic institutions that retain a faint sense that academia is somewhat different from the service industry, have developed a system of rewards, in cash, in privileges or in titulature. It is made to supplement salaries, materially or symbolically, out of a sense, perhaps moral, perhaps amoral, in any case practical, that surplus value should be recognized, without being admitted fully.

As we all know, workers have no control on surplus value, no more than scholars have control of the surplus value they create. What remains surprising is how meekly scholars, and academics, accept that the surplus value they create has, in reality, next to no value to them. In that respect alone academic scholars are workers.

And here, on this controversial note, we shall leave Dante and Virgil when they enter the fantastic and fiery world of Hell 8, with its 10 pits, and finally reach the frozen lake of Hell 9: there they will contemplate Evil Incarnate chewing the brains of three ultimate human evils, three traitors. This will demand another ten pages.

Some References

Blasphemy:

Irène Rosier-Catach. Le blasphème—Perspectives historiques, théoriques, comparatistes. Annuaire de l’École pratique des hautes études, section des sciences religieuses (2018-2019), 127, 2020, pp. 535-550.

Cargo cult science:

Richard P., Feynman. Surely you’re Joking, Mr. Feynman! New York: W. W. Norton, 1985.

Charity and self-love:

Jean-Robert Armogathe, “Conférences,” in Annuaire de l’École pratique des hautes études, section des sciences religieuses (2005-2006), 114, 2005, pp. 333-339.

Epideixis (of scholars):

Philippe-Joseph Salazar, “Nobel Rhetoric, Or Petrarch’s Pendulum,” Philosophy & Rhetoric, 42(4), 2009, pp. 373-400.

Heresy:

Marie-Dominique Chenu, “Orthodoxie et hérésie. Le point de vue du théologien,” in Annales. Économies, sociétés, civilisations, 18(1), 1963, pp. 75-80.

Libido:

Antonio Calcagno, “Hannah Arendt and Augustine of Hippo : On the Pleasure of and Desire for Evil,” in Laval théologique et philosophique, 66(2), 2010, pp. 371-385.

Republic of Letters:

Marc Fumaroli. La République des Lettres. Paris: Gallimard, 2015.

Science as percepts:

Gustavo Bueno. ¿Qué es la ciencia? La respuesta de la teoría del cierre categorial. Oviedo: Pentalfa, 1995.

Skhole and work:

Elisabeth-Charlotte Welskopf, “Loisir et esclavage dans la Grèce antique,” in Actes du colloque 1973 sur l’esclavage, Actes du Groupe de Recherches sur l’Esclavage depuis l’Antiquité (1976), 4, pp. 159-178.

Society of leisure:

Joffre Dumazedier. “The Masses, Culture and Leisure.” Diogenes 11 (44), 1963, pp. 33-42.

Usury:

John T. Jr Noonan. The Scholastic Analysis of Usury, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1957.

Vita contemplativa:

Christian Trottmann. “Vita activa, vita contemplativa : enjeux pour le Moyen Âge,” in Mélanges de l’École française de Rome. Moyen-Age, 117, n°1, 2005, pp. 7-25.

Wisdom of the Ancients:

François de La Mothe Le Vayer. De la patrie et des étrangers et autres petits traités sceptiques (first modern edition). Paris: Desjonquères, 2003.

French philosopher and essayist Philippe-Joseph Salazar writes on rhetoric as philosophy of power. Laureate of the Prix Bristol des Lumières in 2015 for his book on jihad (translated as, Words are Weapons. Inside ISIS’s Rhetoric of Terror, Yale UP). In 2022, the international community of rhetoricians honoured him with a Festschrift, The Incomprehensible: The Critical Rhetoric of Philippe-Joseph Salazar. He holds a Distinguished Professorship in Rhetoric and Humane Letters in the Law Faculty of the University of Cape Town, South Africa.

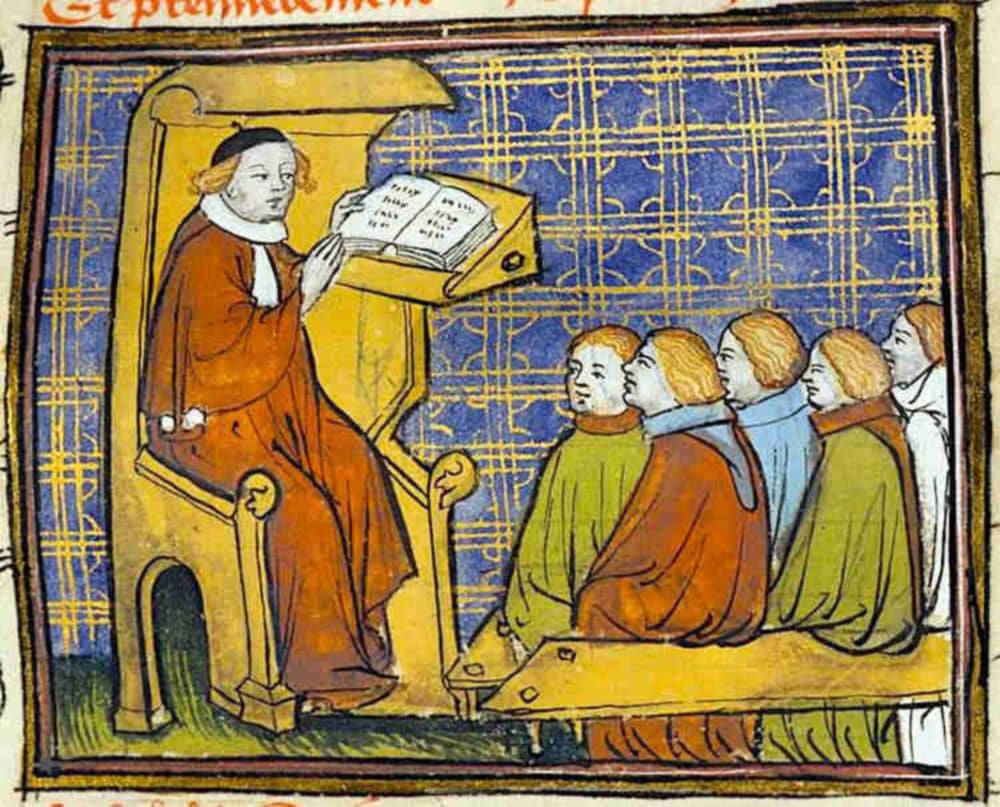

Featured: Chart of Hell, by Sandro Botticelli; painted ca. 1480-1490.