In C.S. Lewis’ The Great Divorce, a ghostly theologian has found himself at the very edge of heaven, having taken a bus from hell. He is invited to remain, though doing so will require that he leave behind the imaginary world of the unreal (hell), and take on the difficult task of being truly what he was created to be.

The conversation has an interesting moment when he describes his latest project: thinking about what Jesus might have accomplished had he not died so tragically young. The proposition is comic, on its surface, a misunderstanding of Christ’s work so profound as to be silly – except that it’s not. “Fixing Jesus” is a very apt metaphor for the task that secularized Christianity has set for itself. And, that I might be clear, every Christian in the modern world is tempted, at some level, to secularize his faith. We all want to fix Jesus.

As much as Jesus is admired in our culture, even quoted on occasion, He remains a bothersome and uncooperative figure. He healed the sick, but seems to have left no lasting plan or program for their long-term care. I’ve even heard the question, “Why didn’t He heal everyone?” Indeed, there is a puzzlement that He still allows us to suffer disease, and is given credit for the deep injustice of sickness itself. Why do children get cancer and Nazis live to old age in the backwoods of Brazil?

Jesus clearly spoke of justice and care for the poor. But He established no guidelines for a just economy, nor did He challenge the economic systems of His time. Sometimes He seems to have avoided the topic on purpose.

Among the most useless pronouncements in our modern culture are the statements, “Jesus never said anything about…[fill in the blank].” This is always said by people for whom what Jesus actually said already carries no weight. “Jesus never said…” means that you may not say it either, except as an example of bigoted traditionalism.

The deep drive of modern secularism has been to tame Jesus, to make Him serve the purpose of the modern project in the construction of liberal democracy. That project requires that all creeds be held in private for the greater public good. Indeed, the modern project would suggest that all religions essentially say the same thing – that liberal democracy and its prosperous peace is the goal of human progress. Inasmuch as Jesus might have done something to contribute to that project, He is useful and good.

This is much more than a culture critique, for that which we can see in the culture has also been written deep within our hearts. It is a worldview we imbibe simply by being born in this time and in this place. That worldview generally sees the world as existing for its own sake (and our lives as existing for their own sake as well). Even when those things are married to some notion of a “greater good,” that good is generally about the world for its own sake. Those things that disrupt the public good are seen as troublesome (at the very least) and needing modification.

Of course, the public good is measured only by this world for its own sake, for its wealth and our general health. Happiness (that fleeting and ever-changing thing) is the common goal of us all.

It would be a mistake, however, to assume that Jesus is focused on some world beyond this one. He is decidedly here-and-now (Matt. 6:34). Indeed, secularism would not exist without Christianity having preceded it. For it is in the teaching of Christ that attention is drawn directly to that which is at hand rather than to life elsewhere. In Christ’s teaching, “The Kingdom of God is among you” (Luke 17:21). What we see today as secularism is a heresy, a false reading and distortion of the Christian tradition. It is the world, in and of itself, as a substitute for the Kingdom of God. A world without depth or meaning apart from its own self.

Christ does not abolish the world (the one that we call “secular”). Instead, He reveals it to be what it is. This material world in which we dwell, to which we are inseparably united, is shown to be the gate of heaven, the bread of life, the medicine of immortality, and so on. For all of these things are not made known to us apart from, nor in spite of their material aspects. Fr. Alexander Schmemann said quite rightly that the sacraments do not seek to replace the material: it shows material to be what it is. In St. Basil’s epiclesis we pray, “And show this bread to be the precious Body of our Lord, and God, and Savior, Jesus Christ…” In the hands of Christ, all bread becomes what it is meant to be, that which alone can truly feed us.

The world does not exist in and of itself, nor is its value and meaning in and of itself. But neither does its true existence, value, and meaning exist somewhere else of which it is a non-participant or an empty shadow. The material world is the locus of the marriage of heaven and earth. In that sense, Christ draws attention to the created order in a manner without precedent. It is the de-coupling of that attention from Christ Himself and the deeper reality that underlies the created order that has given us our present delusion. It is as though all our attention were on human bodies – without souls. As such, we are the dead among the dead.

More than half a century ago, while I was still a child, I recall hearing a number of older people offer the following explanation for the great disasters that had befallen Russia: Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this has happened.

Since then I have spent well-nigh fifty years working on the history of our Revolution; in the process I have read hundreds of books, collected hundreds of personal testimonies, and have already contributed eight volumes of my own toward the effort of clearing away the rubble left by that upheaval. But if I were asked today to formulate as concisely as possible the main cause of the ruinous Revolution that swallowed up some sixty-million of our people, I could not put it more accurately than to repeat: Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this has happened.

What is more, the events of the Russian Revolution can only be understood now, at the end of the century, against the background of what has since occurred in the rest of the world. What emerges here is a process of universal significance. And if I were called upon to identify briefly the principal trait of the entire twentieth century, here too, I would be unable to find anything more precise and pithy than to repeat once again: Men have forgotten God.

The world’s efforts to “fix” Jesus are invariably directed towards either removing Him from this world, or placing Him in the world as a manageable object. Just as the world turned St. Nicholas into Santa Claus (he’s so cuddly!), so Christ becomes a religious mascot of whatever worldly value we want to promote. Solzhenitsyn, in his famous Templeton Lecture, described this process of secularization in profound terms:

Secularism is the forgetting of God, or remembering Him in a manner that is truly less than God. This is the cause of all injustice. Indeed, it is the great injustice: that human beings forget their Creator and the purpose of their existence. When we forget God, everything is madness.

Jesus, have mercy on us and fix us.

Father Stephen Freeman is a priest of the Orthodox Church in America, serving as Rector of St. Anne Orthodox Church in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. He is also author of Everywhere Present and the Glory to God podcast series.

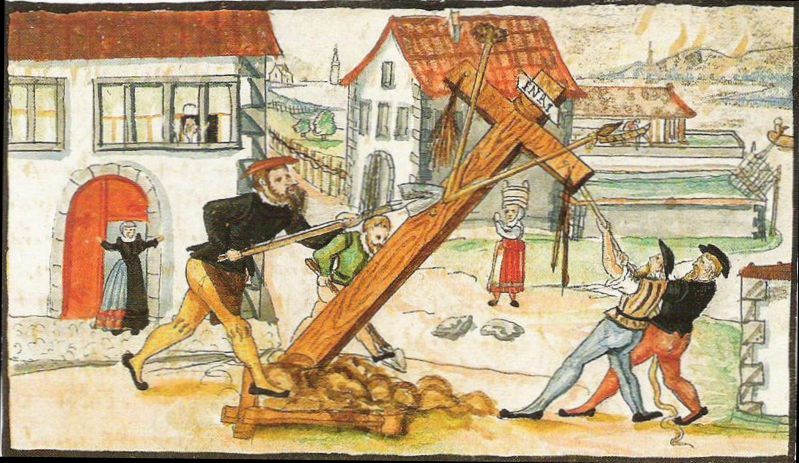

The photo shows Protestant iconoclasm. The caption reads, “Klaus Hottinger pulls down the wayside cross near the mill at Stadelhofen, in 1523.”