Masonic history has been (and still is) the area of predilection for inducements or hasty generalizations, made more hazardous by passionate allegiances, including the eternal conspiracy theory. Conspirators are definitely everywhere. The alleged Freemason plot comes to us from Abbé Barruel whose work consisted of asserting (more than truly establishing) that the French Revolution had been a process organized for decades in lodges and clubs, especially Jacobin, in order to allow the liberal bourgeoisie to seize power.

There is some basis to this intuition, but it must be examined through the small end of the telescope, if only to give some solid arguments to this entirely sensible idea which deserves to have its rational character and historical foundations demonstrated.

Freemasonry was introduced in France in 1725. The founders were three Catholic Jacobites with flowery names, exiles from their own country – Derwentwater, MacLeane and O’Héguerty.

At its beginnings in France, the movement was an almost exclusively Parisian even and even an event of the “Left Bank,” and was born and developed in the district dominated by the Maurist abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, that cosmopolitan district, where lived most of the foreigners to the capital. The meeting of the first Saint-Thomas Lodge took place at an English caterer’s, in the rue des Boucheries, in the Faubourg Saint-Germain; and the first known members were mostly emigrants.

The history of the beginnings of French masonry quickly becomes that of its divisions. Ideological diversification took place within this Parisian setting, around 1732. Very quickly, personalities from London set up Anglican rite lodges: the history of French masonry would be played out for a few years on this original duality.

After 1732, there arose ateliers, under the great lodge of England, whose spirit contrasted with that of the first Masonic houses of Jacobite origin. From its first beginnings, French Freemasonry encountered politics. The reason is not difficult to understand. Founded and animated by Jacobites, the first Saint-Thomas Lodge (the lodge of the grand master), could not but be suspect by the Grand Lodge of London, for it sought to create a rival masonry on the continent. Hence the recognition granted in 1732 by the Grand Lodge of England to Saint Thomas No. 2, which included the Duke of Picquigny, governor of Picardy; M. Chauvelin, State Councilor and former Intendant of Amiens; the poet Gresset, the marquises of Locmaria and Armentières; Mr. Davy de La Fautrière, adviser to parliament and former member of the Club de l’Entresol, who rubbed shoulders with a silversmith named Le Breton. If the left bank provided shelter for the first assizes of the order, soon enough, it became customary to hold meetings either on the right bank, in the hotels of Soissons and Gèvres – famous gaming houses in Paris – or outside the city walls, in some cabaret in the suburbs, at La Courtille or at the Quai de la Râpée.

Worried about the growth of predominantly Jacobite masonry and which therefore was hostile to the Hanoverian monarchy, the Grand Lodge of London created rival lodges. At the end of 1735 or 1736, a third lodge (of Louis d’Argent) was born in rue de Bussy, where the British Ambassador, Montesquieu, the Count of Saint-Florentin, Secretary of State, the Duke of Kingston met. It had for master the Duke of Aumont and for Worshipful Master, a painter and restorer of paintings, by the name of Collins, of English origin, who organized the new rite. A little later, in 1736, the lodge of Coustos-Villeroy was born (which had links with the Protestant bank) whose northern note was strongly marked – it included Germans and Scandinavians who outnumbered the French. Its most active and influential member was an English subject, Goustaud or Coustos, a goldsmith by trade, descendant of French Huguenots who had emigrated after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes.

Paris therefore had four lodges at the end of 1736.

In 1737, Freemasonry, which had enjoyed rapid favor, particularly in high society, established itself in Lorraine with the new court, which gathered there around King Stanislas in 1737. Without being strictly certain, the affiliation of the king is infinitely probable and this Masonic affiliation coexisted without apparent inconvenience with the spirit of the Enlightenment and a religiosity with very emotional forms. You could call it syncretism.

There was thus very early a double current among the freemasons of France: the “Gallican” current, Catholic and anti-Hanoverian, and the “Anglican” current, of a democratic and Protestant tendency. This reformed and liberal tendency ended up supplanting the Catholic and Jacobite elements which, however, survived in the provinces, in particular at the court of Lunéville, thanks to the tenacious actions of three persons: Dominique O’Héguerty, Louis de Tressan and the abbot, François-Vincent-Marc de Beauvau-Craon, Primate of Lorraine.

Many of these noble-lineage Masons, often flanked by an enterprising commoner who was the real animator, did not go beyond snobbery. The Goustaud-Villeroy lodge maintained that the order was not an order of chivalry, but of society; and that although several lords and princes were happy to be in it, any man of probity could be admitted without wearing the “sword.”

The nobility was found more in the Scottish rite, with its glorification of the Christian knight, according to a very hierarchical ceremonial, and with all its traditions and its outlook. This explains the permanence of the two Masonic obedience. One according to the Jacobite rite, esoteric and chivalrous, refuge of an aristocracy still attached to its past splendor. The other, the Hanoverian rite, rationalist, liberal and anti-Roman, welcoming to the big bourgeoisie admiring the Enlightenment. The first developed in societies that remained both seigneurial and Catholic, such as that of Lorraine; the second, naturally, found its chosen ground in Paris.

How did they develop in the rest of France? It is up to historians to respond to that; and this is undoubtedly enlightening in the French regions and the differences in resistance.

These associations were then secret, in the sense of being unofficial and private. To the notion of association, the Masonic practice of the time added those of leisure, pleasure, agreement and spontaneous sociality (outside the State and traditional hierarchies) – all notions that cut across and transcended orders and classes. Put into practice, they had every chance of attracting everybody; and there were many, including those forms of sociability which fulfilled more or less avowed and expected egalitarian aspirations. Relations were based on the principle of equality between men as individuals; and the internal hierarchy of lodges was independent of the hierarchies of the surrounding society. According to historian Ran Halévy, Masonic lodges were thus at the origins of democratic sociability. We can certainly believe that.

It was not until 1737 that the existence of Freemasonry was revealed to a still small public, and at the same time as the political orientation of the movement was revealed. Before that date, the police gazettes made no mention of it. No more than that of London, the French government, could not ignore the activity of the lodges. Its attitude was quite embarrassed. The all-powerful Cardinal de Fleury, who narrowly prevented Louis XV’s initiation into the mysteries of the order, very much warned against Freemasonry. He was behind the police searches carried out in 1737, which brought to light rather suddenly the existence and activity of the Parisian lodges. The police confined themselves to harassment – they bothered a few accomplices, innkeepers who had hosted lodges, but they were careful not to prosecute influential Masons or dignitaries, which would have raised a considerable scandal, affecting the entourage of the king. It was difficult to question or arrest princes, dukes and peers, knights of the Order of the Holy Spirit, a Minister of State (Marshal d’Estrées), two Secretaries of State, not to mention magistrates, ecclesiastics, and so on.

On the eve of the Revolution, there were 650 lodges and some 35,000 affiliates, if not more. It was this new, predominantly Protestant Freemasonry that undoubtedly played a major role in the genesis of the Revolution. The revolutionary principle was at work there, all the more effective as it was more involuntary, implicit and discreet. From discretion to secrecy, there is only one step. The Grand Lodge was regulator until 1773. It was then that the Grand Orient took over. It emphasized the revolutionary trait, and therefore enforced it.

French freemasonry after 1773 was more clearly in contradiction with what remained of order in society – for instance that which traditionally embodied this order, in particular, the Church, which was often reproached for its tendency to recognize the authority of Caesar, and thus alienating the law of Jesus.

Faced with the event called “Revolution,” the “fourth estate,” that of the pen, was divided into two, regardless of rank, status, or fortune. But besides the means available to those who held state power, the fight of the Friends of the King was not fought on an equal footing and it was valued above all by the quality of a thought that asserted itself. It ended in a bloodbath. Those who left in time survived.

But it was easier to guillotine than extract the idea whose line of development (or survival) we can readily follow – from the Friends of the King to ultracism and legitimism, from legitimism to the moral order, from traditionalism to Action française. The continuity of such a current of though tests, in a way, the assertion of the Masonic conspiracy dear to Father Barruel, who had glimpsed a relationship that he was unable to explain and that serial history has begun to shed light on.

“Church of the Republic,” “Missionary of liberalism,” “School of equality” – all would gradually assert themselves as a true society within society.

There is hardly any chance that this history will find today the historical light which is necessary to understand how we went from a seemingly innocent association to a secret society, to a Church of the Republic, whose avowed aim today is to build a counter-Christianity – and therefore to destroy Catholicism.

Marion Duvauchel is a historian of religions and holds a PhD in philosophy. She has published widely, and has taught in various places, including France, Morocco, Qatar, and Cambodia.

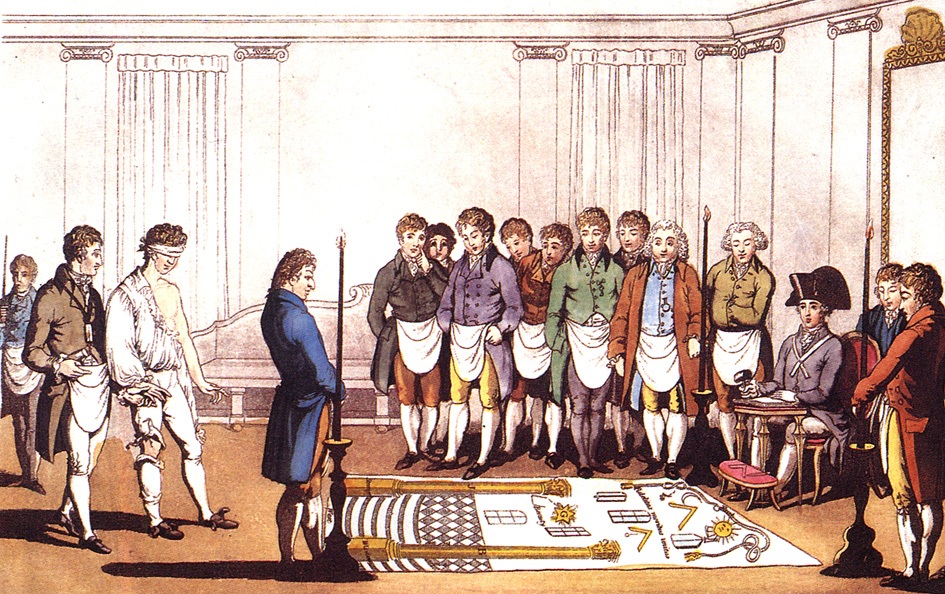

The featured image shows the initiation of an apprentice Freemason, a colored engraving from ca. 1805, based on a French one of 1745.