Ecological frenzy feeds on the fear of collapse and gives rise to many very different attitudes. Between the excesses, the integral ecology of the Church traces a path respectful of all balances which only achieves its full coherence in a process of conversion.

To make the libertine of thought feel how dizzying their emptiness is before the Everlasting, which understands them and which they can only try to understand, in order to prepare their souls for conversion – such is the famous approach of Pascalian apologetics. Fright as a propaedeutic. Anguish as a preamble to metaphysical conversion. And this is also the method of a certain ecology of the doom-and-gloom variety.

The call for “ecological conversion” is fueled by the anguish of collapse. It is necessary to describe a crisis so that the feeling of ecological urgency arises, and with it the call for a radical change of lifestyle, a reversal of perspectives. The almost metaphysical vertigo, which engenders the consideration of the fragility of life and its conditions of existence, therefore, seems to entail a religious attitude.

It is one of the paradoxes of our time to seek in ecology the most ultimate contradiction to its technical frenzy. As if the consumption of organic quinoa seeds could make modern humans forget their addiction to new technologies. The recent investitures of so many mayors bearing this label of ecology, during the last elections in France, revealed both the omnipresence of the question of ecology in people’s minds and the great diversity of realities that it covers. There is Cassandra with apocalyptic prophecies, aka, Greta Thunberg now consecrated as priestess and pythia of this new spiritual order, which has given rise to public demonstrations of disturbing fervor, when it does not use openly pagan voodoo rituals, as in the case, for example, of the term “Demeter” used in viticulture.

It may be enlightening to read on this subject, Murray Bookchin, a thinker who worried about the epidemic rise of a “spiritual” ecology, and according to whom ecological problems are emptied of all social content and reduced to a mythical interaction of natural forces. Even among some Christian environmentalists, it seems that the way to Heaven sometimes resembles a bike trail, so that the question arises whether the way is even now clearly understood. Thus the “Green Church” label recently set down by the French Bishops’ Conference might well raise questions. Should the epidemic rise of this spiritual ecology worry Catholics? Is it a prelude to a radical conversion of the soul towards its Creator and Savior, or an ersatz conversion within the Church itself?

It appears that the relationship that man has with the Earth, which welcomes and precedes him, brings to light three possible attitudes that engage the individual in various ways.

Surface Ecology

The first attitude is a surface ecology, well-intentioned but really just navel-gazing, and steeped in inconsistencies. This explains the paradox of the Whole Food movement in the United States, offering “organic” products from all over the world, and also prospering on the awareness of the undeniable ravages of an ultra-productivist agricultural policy on the other side of the Atlantic. The recent takeover of this sector by the giant Amazon shows how much the logic of the market has taken hold of this attitude to better serve increasingly hegemonic group interests. In La Cyberdépendance: pathologie de la connexion à l’outil Internet (Cyberdependence: Pathology of the Connection to Internet Use), the psychiatrist Philip Pongy writes: “Capitalism is a past master in the art of recovering everything, including its most critical and virulent opponents. Promoting conviviality on Twitter strengthens Silicon Valley. To talk about degrowth on TV is to serve the entertainment industry.”

Thus, the consumer who eats quinoa seeds and soybeans from the ends of the earth, after leaving the overheated gym, can afford good intentions at little cost. The attention paid to the nutritional quality of food from large-scale distribution only reinforces the domination of a system of culture and consumption, sinful in its very essence. This ecology in no way educates the selfishness of consumers, governed by their pleasure principle, but rather adorns their impulses with a green polish. It is therefore not a question of a conversion of the individual but of the exaltation of his desire. It is not surprising that this pageantry-ecology can culminate in the apology for PMA, or in protests, because the endocrine disruptors contained in the waters of the Seine from the contraceptive pills discharged by Parisians which are causing a sex-change in fish, thus promoting “gender fluidity” among the lower orders. The primacy of the individual at the expense of the Whole is thus the matrix of this first green imposture.

“Deep Ecology”

The obverse of this surface conversion, is the second attitude, which is not mistaken in calling itself “deep ecology.” This Malthusian and guilty ecology, far more ideological, makes the Whole triumph over the individual. Humans are too many; they are a parasite; potential polluters who can be easily intimated by their carbon footprint, and must be destroyed. The appalling number of vasectomy treatments, the new face of this thousand-headed hydra that is the culture of death, illustrates the dissemination of this thesis to the general public. This ideology of Greenpeace activists, who immolate themselves when a whale is slaughtered, or castrate themselves to avoid giving life, is part of a vegan and animalist movement ranging from the agit-prop of League 214 (which wants to highlight the suffering of animals by shocking acts) to the candidates of animalist parties that we saw appear during the last European campaigns. It is no longer a question of exalting the desires of the subject, but of refusing any preeminence of human nature.

In this new face of transhumanism, man is nothing more than the link in a chain of mammals, all equally capable of suffering, and therefore all potentially subjects of law. The regulations protecting farm animals are thus underpinned by the recognition of their sensitivity; that is to say, of their capacity to feel pleasure, suffering and emotions. In France, it is Article L214 of the Rural Code (codification of a law of 1976) which mentions their character as sensitive beings. In 2015, the Civil Code recognized that animals are sentient beings, who yet remain subject to the regimen of property. On January 29, 2021, the National Assembly adopted at first reading, with modifications, the bill aimed at strengthening the fight against animal abuse.

Integral Ecology

Consideration of the singular vocation of the human soul and the duties which bind it to Creation, which has no rights but towards which the human sou has duties, can resolve this antinomy. Man is not an animal like any other precisely because his freedom makes him capable of taking care of Creation that is entrusted to him. This answers the anti-speciesist.

Ecology can thus only be chosen in an integral way; that is to say, by involving all dimensions of existence, and by requiring coherence. Such a consideration, to which the luminous encyclical of Pope Francis, Laudato si, beckons, is therefore at the same time an ecology of nature, a human ecology and an ecology of peoples, with each of these three orders meriting its balance to be preserved by the application of a principle of precaution. Ecology, which seems dangerous when it abolishes all transcendence in order to spiritualize matter, takes on meaning if it opens a Franciscan path of poverty and sobriety that takes care of the common home by considering creation as the image of the Creator, a mirror of His greatness. The “ecological conversion” is therefore neither ontologically nor chronologically first – it is the consequence of the choice to follow Christ, so that the most successful model of ecological life is undoubtedly the monastery.

Maylis de Bonnières is a French educator in philosophy. (This article appears through the kind courtesy of La Nef. Translated from the French by N. Dass).

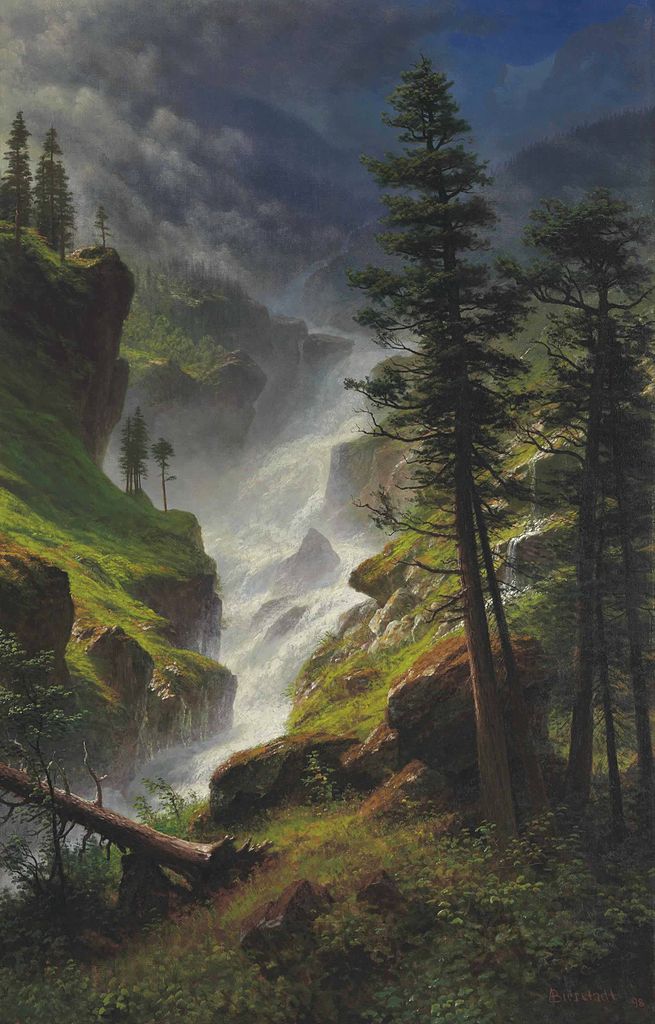

The featured image shows, “Rocky Mountain Waterfall,” by Albert Bierstadt, painted in 1898.