Der Prinz.

Was ist sonst? Etwas zu unterschreiben?

Camillo Rota, his secretary.

Ein Todesurteil wäre zu unterschreiben.

Der Prinz.

Recht gern.—Nur her! geschwind.

Camillo Rota (stutzig und den Prinzen starr ansehend).

Ein Todesurteil—sagt’ ich.

Der Prinz.

Ich höre ja wohl.—Es könnte schon geschehen sein. Ich bin eilig.

Camillo Rota (seine Schriften nachsehend).

Nun hab ich es doch wohl nicht mitgenommen!—Verzeihen Sie, gnädiger Herr.—Es kann Anstand damit haben bis morgen.

Der Prinz.

Auch das!—Packen Sie nur zusammen; ich muß fort—Morgen,

Rota, ein Mehres! (Geht ab.)

Camillo Rota (den Kopf schüttelnd, indem er die Papiere zu sich nimmt und abgeht).

Recht gern?—Ein Todesurteil recht gern?—Ich hätt’ es ihn in diesem Augenblicke nicht mögen unterschreiben lassen, und wenn es den Mörder meines einzigen Sohnes betroffen hätte.—Recht gern! Recht gern!—Es geht mir durch die Seele dieses gräßliche Recht gern!

PRINCE.

Anything else, anything needs signing?

CAMILLO.

A death warrant, subject to Your Highness’s signature.

PRINCE.

Perfectly happy to do so! – Show here ! Quick!

CAMILLO (starting, looking fixedly at the Prince).

A death warrant, I said.

PRINCE.

I’ve quite understood. It might have already been dealt with. I am in haste.

CAMILLO (looking at his papers).

It seems I haven’t the warrant with me. Begging Your Highness’ indulgence. Tomorrow will do.

PRINCE.

Let it be then. Gather these papers up. I must away. We’ll see to the rest later, Rota.

CAMILLO (shaking his head, as he collects the papers).

“Perfectly happy to do so!”–A death warrant, Perfectly happy to do so! At such a moment, I would not have had him sign, had the murderer struck down mine own son.–“Perfectly happy to do so!” The words cut through my soul. (Exit.)

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Emilia Galotti.

Until the 20th Century, when Palestine suddenly found herself a target to thousands of usurpers, likely Aryan in origin but purportedly adhering to an ancient Semitic belief, others of our “tribe” had been celebrated throughout the world for two disciplines: music, and mathematics. Residing as he does on the art world’s fringes, Mendelssohn has little acquaintance with the latter science. But music…

Today, faced with the jubilation amongst the Jabotinski soldiers brought up on the Holocaust Education Project as they raze Gaza and put her people to the sword, it may not be otiose to review the thoughts, feelings and intimations of immortality once prevalent in Europe and more especially in Judaism. Bearing in mind that our tiny sect of dissidents, day-dreamers and free-thinkers sheltered under the wing of a more advanced religion eschewing the notion of vengeance, nämlich Christianity, which, before sinking beneath the waves in 1914, permeated life both East and West of the Urals.

***

Can one imagine Franz Schubert joining the Jabotinski forces to perpetrate obscene murders in Gaza? Obvious perhaps the answer, less obvious the cause, which lies in the structure of the musician’s mind.

Without a word, an image, without surface, weight or volume, the greatest space-time density of all human activity occurs in classical music.

Breasting the waves between the pre-conscious and conscious, it is in music that thought manifests its changes, almost unobstructed.

Spurred on by love for one’s fellow man, swayed by no authority other than himself, the composer sets out a challenge with which he struggles, before inventing the next. Meanwhile heeding Wilhelm Furtwaengler’s warning to avoid outright abstraction, a domain where few men will care to follow.

***

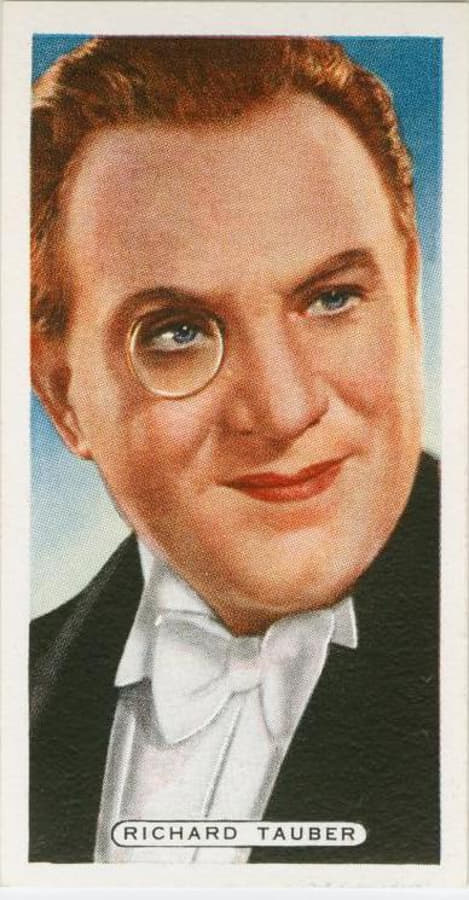

In order to keep to actual matter that the reader can himself hear and judge, we propose to listen to Richard Tauber, an Austrian tenor of Mendelssohn’s er, “tribe,” in the tricky Lied number 8, from Schubert’s Winterreise, “Rückblick”—tricky, as making use of the technique I call S’legato—a quasi-legato where each note is detached as though spoken and nearly as distinctly as though it were staccato. In this recording made sometime in the 1920s, chosen for its singular qualities (although the wax imprint is fresher on other recordings), Tauber’s pianist is probably a Russian coreligionary, Mischa Spoliansky.

Straight off, one acknowledges that Tauber’s marked Austrian accent, flamboyant personality and above all, style of singing—idiosyncratic perhaps but rock-solid—are completely out of the fashion, in favour of the current impersonal-arbitrary; but, as Forbes-Robertson said, “I know only the BAD old style, and the GOOD old style.”

Be that as it may, “Out of the fashion” is a conceit, while Richard Tauber is still considered to be amongst the most eminent singers of all time.

Unlike Fritz Wunderlich, for example, Tauber’s voice is neither notably beautiful nor melodious but rather proteiform, “all Things, to all Men” (1 Corinthians 9).

Although the song-line seems enormous, moving at will from the faintest ripple to a tiger-like bound, that is an illusion proper to a great artist: Tauber was no Heldentenor. The true volume was quite unsuited to Verismo or Wagner, not something Mendelssohn would deplore.

***

Now to “Rückblick” (Winterreise, Lied 8, Franz Schubert to Wilhelm Müller’s cycle of poems).

In Tauber’s interpretation—and Spoliansky hardly qualifies as a spare wheel!—the listener’s attention is drawn neither to the interpreters, the voice, the keyboard, the words of the poem nor even the score in and of itself but rather to the whole—”a single ardent thought,” as Alastair Macaulay once wrote. The Lied becomes a “thought-object,” an idea that takes to the open seas relative to Müller’s text, an idea intangible—but intelligible. The two artists’ submission to the idea allows the shifts (Schattierungen, Zwischentöne) that characterise Schubert to manifest; shifts that guide one’s thought to indefinite unknowns, the metaphorical “ferne Geliebte.” This, despite each word, each note, being clearly enunciated and given proper weight.

Most likely, song preceded spoken language, and thus at first, most languages were doubtless tone-languages, i.e., the same phonemes produce two or more words of different meaning, depending on the frequency. In the Indo-European group, although Swedish and Norwegian are readily acknowledged to be tone-languages, English is notoriously so. Black bird and blackbird are differentiated only by tone. As for words thought to be single-tone (cat, dog, day…), if one listen carefully, they have two or more tones. Within the Western system of tonal music, the singer remains within the perimeter traced by the overtone, halo, aura, Oberschwingung around each note, without exceeding a quarter-tone; the aura nevertheless exists, nor is it entirely under conscious control.

In the recording with Tauber here, while each verse has its fullness, the arrow necessarily falls on the verb. Take the words “glühten” and “geschehn.” In theory, F sharp/E on “glühten,” and G/ D on “geschehn.” However, around each of the verbs’ two notes, flits an aura. Whereas the nouns “Krähen” and “Bäll” (harshly stressed by most singers apart from Tauber) are marked with the little symbol for “accented,” these accents are less telling than the verbs “glühten” and “geschehn,” to which Tauber lends the halo or aura, faint, fleeting but there nevertheless.

A further, capital aspect pointed to by our coreligionary, the musicologist Elam Rotem: before the War, the strong beat on the melodic line—here, the voice-line—was not mechanically pasted onto the orchestral strong beat—here, the keyboard. There was nearly always a tiny and deliberate gap, a hiatus, leaving the soloist a certain freedom.

Plainly, rhythm and melody are the two more primitive components of music, while harmony and counterpoint occupy the higher planes. The moment a soloist aware of what he decides “staggers” the vocal line relative to the keyboard, a slight syncopation occurs and a slight dissonance as well. For example, the syllable “Krä” of Krähen, on E; rather than placing the Krä on the A-E chord of the keyboard, Tauber presses it closer to the dissonant E/F sharp of the keyboard chord—which adds something like a further “voice” to the keyboard + vocal lines.

With many such moments within scarcely two minutes’ space, Rückblick quits the domain of “charm” and “melody” for that of thought, where out of the dusk appear ideas and emotions which now strike us as quite foreign. Indeed, under the massed blows of Hollywood, video-games, pop-rock-techno pseudo-music and GAFAM entertainment, what Schubert and his like once represented have vanished from the Earth, rather like sparks flying towards us from stars and planets extinct thousands of years ago.

If, amongst our purported co-religionaries one were to meet up with an Artur Schnabel, a Richard Tauber, a Clara Haskil only… or perhaps even an Elam Rotem who sticks to his own kale-patch, namely, early Italian music… well, a Man may Dream! As it happens, more’s our rotten luck, we are saddled with the Recht Gern faction, the Hélène Gordon Lazareffs of this world who according to her magazine’s designer Peter Knapp, was wont to invite to Sunday fêtes at Louveciennes, most excellent company such as the pilot who dropped the atomic bomb on Nagasaki. And a Knapp can be found to boast of it.

Text of the Lied “Rückblick.”

Es brennt mir unter beiden Sohlen,

Tret’ ich auch schon auf Eis und Schnee,

Ich möcht’ nicht wieder Atem holen,

Bis ich nicht mehr die Türme seh’.

Hab’ mich an jeden Stein gestoßen,

So eilt’ ich zu der Stadt hinaus;

Die Krähen warfen Bäll’ und Schloßen

Auf meinen Hut von jedem Haus.

Wie anders hast du mich empfangen,

Du Stadt der Unbeständigkeit!

An deinen blanken Fenstern sangen

Die Lerch’ und Nachtigall im Streit.

Die runden Lindenbäume blühten,

Die klaren Rinnen rauschten hell,

Und ach, zwei Mädchenaugen glühten. –

Da war’s gescheh’n um dich, Gesell!

Kommt mir der Tag in die Gedanken,

Möcht’ ich noch einmal rückwärts seh’n,

Möcht’ ich zurücke wieder wanken,

Vor ihrem Hause stille steh’n.

The soles of both my feet burn,

Though I tread upon ice and snow,

I will not again catch my breath,

Until the towers I can no longer see.

I stumbled on every stone,

As I hurried out of the city;

Rooks threw bits of snow and hail

Upon my hat from every house.

How otherwise you greeted me,

You city of impermanence!

At your bare windows sang

The lark and nightingale in quarrel.

The round lindens were in bloom,

The clear gullies rippled brightly,

And, ah, two eyes aglow of a girl!

It was all over for you, my friend!

That day comes again to mind,

And I want to look back,

I want again to stumble back,

And stand still before her house.

Mendelssohn Moses writes from France.

Featured: Richard Tauber, cigarette card, ca. 1932.