This month we are very pleased to have a conversation with Daryl Kane (DK). This interview was conducted by Grégoire Canlorbe (GC), on behalf of The Postil. Briefly, Daryl Kane is an American politician best known for his book, Cultural Cancer: Treating the Disease of Political Correctness. He also hosts the well-known podcast, Right Wing Road Trip, and serves as the editor of the journal, Revenge of the Patriot. He will run as a Republican candidate for the President of the United States in 2024.

GC: You are campaigning for the presidential election of 2024, under the banner of Christian morality, economic freedom, ethnic identity, and the fight against leftist cultural cancer. On the issue of immigration, how exactly does your program stand in relation to Trump’s politics?

DK: Immigration obviously is such an important topic, and I give Trump credit for emphasizing it in his campaign. Rhetoric aside, how much has he achieved? I’m not sure. I think a lot of good has been done – but, really, when we’re talking about slowing, even stopping the tide, this is a stopgap mentality. It’s not a conversation about solutions.

Very clearly, the American people, and really just about all citizens of Western nations… Look, this is and has been political warfare, and the damage sustained is reaching, and has really passed, a point where we can just end this nonsense, without also taking remedial, restorative measures.

This is naturally a very charged topic and one which must be approached with sobriety, but also with care and humanity. On the one hand we have a ship that is sinking, and, you know, we can’t just plug the holes; we have to also start removing some of the water. But we’re not talking about water, we’re talking about God’s children. So, you know, perhaps to the chagrin of some – no, I’m not just going to arbitrarily throw everyone out. But you know, I actually don’t think we really have to either.

One big talking point for Trump is about moving us to fully merit-based immigration, which strikes most conservatives as a tough, sensible response. Certainly, this is better than the prior lunacy. Things like “diversity visas,” which for me is a term that I often instruct people to pause for a moment and think about. What exactly is a “diversity visa?” Well, obviously it’s a seat in our country, which we are setting aside, reserving for people on the basis of them being less similar to our current citizens than other would-be immigrants.

For me, you know, I’m not sure we do want to move away from identity-based immigration. I think maybe we keep a lot of that stuff, and by the way this pertains to domestic programs as well, where you know we spend billions a year to promote this or that group; really, any group that we don’t usually associate with mainstream Americanism.

Maybe we keep a lot of this diversity infrastructure, at least the concept of them – but we actually invert them; or, you know, replace them with a desire to reinforce or advocate for traditional Western identity. Maybe we start setting visas aside for, oh, I don’t know, white, English speaking Christians? (Laughs)

You see, no one ever really bothered to explain to Americans why they needed things like diversity visas, diversity scholarships, etc. They were just sort-of injected in, draped in this very flowery, humanistic rhetoric. I think it’s time to start talking about things like homogeny-visas and see what happens when the Left has to justify why it’s OK for them to play this game, but not us. Let’s have a national dialogue about the benefits of both ends of the spectrum, and let’s see which of the two seems more beneficial at this point in time.

And, look, I’ve said this too. I’m not an anti-diversity person. Diversity can be good; it can be bad. I do like being able to enjoy all sorts of unique ethnic cuisine in cities and things of that nature. A lot of people scoff at equality now; and, you know, I don’t know.

That ideal still resonates with me, and I don’t want us to lose that ability to make friends from different places, to connect, and be decent to one another. But I think quite clearly the level of diversity which we now have, frankly—and this is putting it mildly, it’s plenty.

A lot of the kids look at these issues and see only one way out, secession, war, etc. I don’t see that at all. I think we get so caught up with this mess that we overlook an important fact which is that when we talk about the violent demographic shifts forced on our nation by the Left, it was virtually all done peacefully.

The way out of this is really to take what they’ve done, recognize that they’ve established a precedent, both legally and morally for us to peacefully do just the opposite. It’s not an overnight thing. It’s a gradual thing; and something that we work on, together with other nations confronting this same challenge; putting together the very same global initiatives to save our nations which were put in place to doom them.

And we balance this with the human or spiritual element which must always remain front and center. This is a Christian nation, and the golden rule must always be supreme on our soil. Look, if you’re a true Christian, that is to say you’re aspiring into the faith, rather than using it as an excuse for sin – you’re welcome here; you’re safe, period; end of discussion.

We’re not going to treat people differently based on what they look like, or if they have accents, or stuff like that. My gosh I have so many great friends from all different communities and most of them will be totally lock in step with us on all of this.

There’s the micro and the macro. On the micro, we’re going to continue treating everyone with decency, courtesy and compassion; while on a larger scale, we’re going to gradually, but methodically, steer our nations away from the cliff. It’s a tough balancing act. But I truly believe that we can, and must, do it.

GC: While the Soviet Union (like North Korea nowadays) stood up against free enterprise and the bourgeois mentality, it was far from pursuing a “cultural Marxist” agenda in the sense that is commonly understood in the West, namely, the leftist attack against traditional family, marriage, heterosexuality, race preservation, and militarized nationalism. Marx himself was quite a conservative beyond his concern for overthrowing the bourgeoisie and abolishing private property. How much relevant is the use of the locution “Cultural Marxism” in that regard?

DK: Yeah, I mean you’re talking a bit of history and semantics here which is good and meaningful, of course. Is the term “Cultural Marxism” hugely effective in pushing back on these things? Maybe not. I think I follow your point and it’s a good one.

There’s a trap maybe in over complicating this stuff, making it less accessible to common, decent people of all backgrounds, who I feel are our natural voters. I use terms like evil, perverse, deviant, etc., which I think well-meaning, sensible people can pick up on right away. Cross dressers reading to children at gun-point, I feel, is a great, visceral talking-point, which resonates with really all people around the world, save a small handful of “true believers” driving this agenda.

I think bold assertions of truth have tremendous power to move the attitudes and sensibilities of the public – and my major critique of mainstream conservatism is that it lacks the sort of guts or spine that are required to truly impact public opinion. The attitude has been, you know – look the world is changing and we might not like that, but we’re going to have to bend a little bit to remain relevant – which to me is not only totally feckless, but really even, speaking pragmatically, just a losing strategy.

The newer model which has been percolating, which I and others represent, is one of recognizing that, yes, things are changing and that change is the problem and must be confronted head on, lest we surrender the future. But rather than finding our place in an increasingly shrinking land mass, it’s more about, OK, let’s examine the things which are driving these changes; let’s attack these things; and let’s craft a platform which takes the fight to the enemy’s territory, in order to take away some of the territory they occupy.

The difference here is that one approach is about transacting for a place in a broken future versus fighting to create a new one. It’s only natural that when voters get a chance to choose, they will always choose to go for the guy who is fighting for them – versus the guy who is seeking to negotiate terms for their surrender.

Where terms like “Cultural Marxism” have relevance is in conversation with the current authority figures within the GOP. You know, the mostly brain-dead losers, who have been steering this ship over the waterfall. Really smart guys, old money types, serious intellectuals. (Laughs.)

Terms like “Cultural Marxism” makes them feel comfortable and important, because it incorporates the concepts which they pinned all of their ideas on to; ideas like size of government, Capitalism vs. Marxism, etc., things which, oddly enough, the younger crowd is increasingly less and less interested in, than the things which really matter, which are, of course, culture and identity.

There’s a lot of hostility towards this generation, the boomers, and I certainly understand it. But, look, this thing is going to be ours. There are too many dynamic laws at work which dictate that. Most obviously, this generation is on its way out, so to speak.

I think the tone in which we approach them is important, to make this thing more seamless, to really unite the conservative coalition which, really, for all intents and purposes, is what we used to refer to simply as the American people. We don’t want it to be nasty or overly combative. Their ideas are weaker than ours. We don’t need to rub their noses in that fact. Let’s lead them. That’s what I’m about.

GC: As an actor and producer, you enjoy first-hand knowledge of the American movie industry’s ideological agenda. Yet you are fond of describing 2005’s Revenge of the Sith, not only as an eternal masterpiece, but as one of the keys unlocking the “mystery” of your political platform. Could you tell us more about it? Between Siths and Jedis, who may be seen as the equivalents (in George Lucas’ universe) of Marxists?

DK: (Laughs!) I see you’ve been reading all of my tweets and doing your homework. Don’t believe everything you see on the internet. The truth about me and who I am really isn’t all that impressive, or important for that matter. I’m a normal guy who grew up in crummy apartments and figured out how to make enough money to live by myself in major cities, drive sports cars and buy all these fancy, magical foods they call organic. (Laughs)

I’ve made a ton of mistakes along the way, and I’ll, no doubt, be confronted by them all, by the time this thing is finished. Of course, anytime a person comes along and suggests raising ethics, civility and public decency, there’s this tremendous excitement when the opposition discovers they themselves are somehow less than perfect. Spoiler Alert: I too, am less than perfect!

And, you know, there’s a trap here too, where we as Christians say only Christ is perfect, but I’m forgiven so all of these pet sins are OK. Of course, they’re not. And I’m not giving myself or anyone a pass. But the other trap is to be intimidated away from aspiring to goodness, because of your own imperfections. Let them focus on bloodying my nose, drawing distinctions between myself and my ideals.

Now, I work every day to reduce these distinctions, to be a better man, to better walk the walk, and I’ll never stop on that. But, at the end of the day, we all do fall short, be it an inch or a mile, and I am; and, not shifting responsibility here, but our generation grew up in an age of remarkable social chaos. I think now, more than ever, we all have unique baggage, scars, shortcomings; and it can almost be overwhelming.

That’s the challenge for our generation – to really become the CEOs, to take it all, to be the buck-stops-here generation, to ultimately forgive each other for where we’re all at, and somehow reform proper families, proper communities, and take all of this nonsense to our graves. Give our kids the type of world that our parents threw away; only now, maybe, just a little stronger, a little more sensitive to the threat of complacency.

So, yeah, you’re all going to get to look at me and judge for yourself if I’m up to the task of turning this ship around and getting us back on course. But whatever comes my way, know this, know that none of it will ever move me off of my ideals, my vision for the country and the world.

A bit of a tangent there, oops. What was the question? Yes, Star Wars. Great topic. I don’t do the Game of Rings or Lord of the Dragons stuff (Laughs), but, of course, we all love Star Wars, right? As for the prequels, I’m someone who was growing up when they came out. I was the target demographic, and forgiving a few things in Episode 1, the next two for me, are easily high-points in the series.

At the time, of course, there was this incredibly vitriolic response from a small crowd of, what we basically now call, trolls, I guess, who managed to drive public opinion on these really charming, fantastic and poignant movies. What does all of this have to do with my campaign, exactly? I think in your question you’re asking for parallels: Who are the Jedi, who are the Sith, etc. The Lucas’ films deal with archetypes and the subconscious, so there’s a bit of an astrology-thing at work, where we can really all read into it and see ourselves as the heroes, and our enemies as the villains.

Realize that Lucas is a 60s era progressive, and, you know, we can probably infer certain things about his views in relation to the work. At that time, when he was coming of age, they had this idealistic desire to spread love and peace. And that, in and of itself, while perhaps misguided, is not an ugly thing. So, I think from Lucas’ perspective, his framework is probably that the rebellion related to progressivism and the Evil Empire reflected conservatism.

But again, what made his movies so moving, on a massive scale, is that underpinning archetypal, universal mythology. And in a way (and I write fiction for my family, so it’s something I relate to), in that type of storytelling, you’re more of an investigator; you’re drawing from this primordial well. You’re refining it, discovering it—but you’re not the source of it. So sometimes the thing you are looking for, sometimes it’s not necessarily what you’re drawing forth.

So, that’s the backdrop, I think, of the work. But what Lucas also puts into his work is very classical, traditional sensibilities. This is really what that backlash was about. Ugly people who want to see ugly things – Tarantino kind of crap. You know, we’re talking about people who are still, to this level, viscerally upset about the fact that Han is no longer shooting first, or whatever.

Here, what you really have is an artist acting responsibly in his role as content creator. He stepped back and thought, you know, I think, they get that he’s a bit of a Maverick; but that scene struck him as a little bit too much of a “Dirty Harry” kind of thing, so he adjusted it.

This is a thing to be applauded, frankly. And the prequels, really, in all senses, visually, thematically, they’re very classical; much more so than the originals, and for a certain percentage of the original fandom, the type who totally missed the original message, obese basement-dwellers, frankly, they just loathed them because of it.

You know, to me they are very beautiful films, visually, thematically and even the tonality of them all. They’re designed to be digestible; for all ages; and yet they’re packed with all of these rich literary themes and traditions. Really, if a kid watches all six movies, he actually has a pretty solid foundation for Western storytelling tradition. To me, really, a lot of these so-called critics, they really reveal their ignorance of film history.

There’s a lot of old Hollywood in the prequels, the old James Dean movies Lucas grew up watching, as one example among many. Attack of the Clones to me is very much a sort of Rebel Without a Cause or East of Eden set in space. Revenge of the Sith, to me, clearly the best of the lot, is quite Shakespearian, a combination really of Romeo and Juliet and Macbeth.

These are really terrific things which he draws from, works which have stood the test of time, and Lucas really blasts it all into space, using the best technology available; technology he created out of necessity to properly illustrate his imagination. All of this other stuff now, the Marvel stuff, whatever, it’s all owed to him, at least, in this regard.

Now I think, Lucas may be rethinking some of his own progressivism, as he most clearly sees what Disney has done, which I regard as a rather high act of violence against the collective psyche of the American people. It’s a topic I take very seriously, and really, is a big part of my Defense of Culture Act (D.O.C.A.). I’ve been clear on this.

The entertainment industry is really a big, big part of the problem. We’ve given them a pretty long leash; and where we’ve ended up, where essentially every movie, every show, every network is dedicated to lecturing, degrading and humiliating traditional Americans – is just not acceptable. It has to stop, and it’s going to stop. Period. End of discussion.

This is where we really break the mold on traditional conservatism, which plays within these polite rules of engagement, and as a private sector thing; this is just something we’re supposed to accept as being out of our control. You know, maybe work on some lame little alternatives of our own and hope that in 50 years our programs are watched by more than 3,000 people. Read my lips America. This ends under a Kane administration.

Most likely we’ll start by imposing some common sense ethics, like we had with the Hayes code, but more tailored for the times. If you want to create some nihilistic art film about the evils of colonialism, I don’t know, maybe there’s a place for that. But if you’re going to sell these ideas, you’ve got to do it on your own product. You aren’t going to be allowed to take Captain America, or whatever, and rebrand him as a bi-racial trans-sexual; or reduce War and Peace to a diatribe about victim-feminism.

And, you know, if you can’t comply with this pretty basic expectation, maybe there really just isn’t a place for any of that stuff in this day and age any longer. The first step for me as POTUS is going to be to tell them something they’re not used to hearing, which is a very special, two letter word called, “NO.” Their reaction will determine steps 2, 3, etc., until I’ve resolved the situation to the satisfaction of the American people.

So, what has just happened with Star Wars, I feel is a turning point, because the end result was such garbage, so devoid of anything remotely relatable or meaningful to anyone, even the targeted demographics and identity groups, so that this cherished franchise is basically dead, what 5 or 6 years later? It’s out-and-out parasitism, to take over cherished names, characters and stories, inject them with your intellectual graffiti and extract a few billion dollars out of the American people before they catch-on, and walk away for good. And, you know, you can’t really fix this stuff now; the actors are dying off; the characters are dead. You’d basically have to annul the new movies entirely. I don’t know, maybe we do that. (Laughs)

You’d better believe Disney is on my radar, I think, accounting for something like 80% of the highest grossing movies of 2019 which effectively makes them a monopoly; and what they are churning out is basically enemy propaganda. Very sad to me that a name and a company known for wholesome, family-centric entertainment, has been transformed into something so dark, perverse and distorted.

This stuff is no longer fit for adults, let alone children; and I’m very concerned about the whole thing. There’s this deep visceral hatred for boys in particular, which is so concerning, especially when you see it forced so awkwardly into something like Star Wars, where the original target audience really was young boys.

So, my DOJ, we’re going to look into this stuff. Maybe it’s a coincidence that virtually all of the good guys are women and minorities and effectively all of the villains are these extremely pale guys, almost caricatures of whites and men. But you know, maybe it’s not. The point is we’re going to find out. With such a massive impact on our shared cultural experience, we’re going to need to dig in a little deeper to get to the bottom of this stuff.

I want to see the development notes. I want to see if they were targeting specific groups. And if they are, especially when it involves entertainment for young adults, then you’re going to see me take steps, maybe unprecedented steps, on a Federal, Executive scale to address them.

A bit of a longwinded response again…What does Revenge of the Sith have to do with my campaign? That’s a more ethereal, metaphysical type of thing which I think is best to let you guys figure out as you re-watch these films, which I’m told are now becoming popular with the zoomers.

I do think in a strange way, it coincides with an awakening on so many more things we’ve been told are “down” but in reality, are “up.” The neat thing about this movement, why I became so encouraged years ago, is that it’s so very synchronistic.

You’ll find people like myself and others who are totally unaware of each other and their work emerging from various corners of the world presenting very similar ideas, even using identical lingo and verbiage, terms like “degenerate,” for example, which I’ve always used to describe this stuff, being used by everyone.

This is a very good sign and something which should terrify our political opponents, whose ideas never really seem to spring up on their own; their verbiage and lingo is so unnatural, so fundamentally backwards that they cannot possibly spread without a massive propaganda apparatus. Step one is cut the monsters legs off; stop the apparatus. Isolate the beast. That’s really the idea and culture. Entertainment is a very major part of this, which the political Right must confront in a very assertive manner. And that’s what we’ve done and what we’ll continue to do.

GC: It is not uncommon to speak of Catholicism as a Pagan religion venerating statues and preserving Indo-European archaisms, whereas the spirit of the Lutheran Reformation (culminating in the American civilization) is supposed to have ended the Catholic version of the old Pagan world’s tripartite order, namely, the king and the warlike aristocracy, the Church, and the commoners – for the benefit of the advent of a burgher-civic order, fully in line with the Christian mindset. As a Protestant politician, do you share that claim?

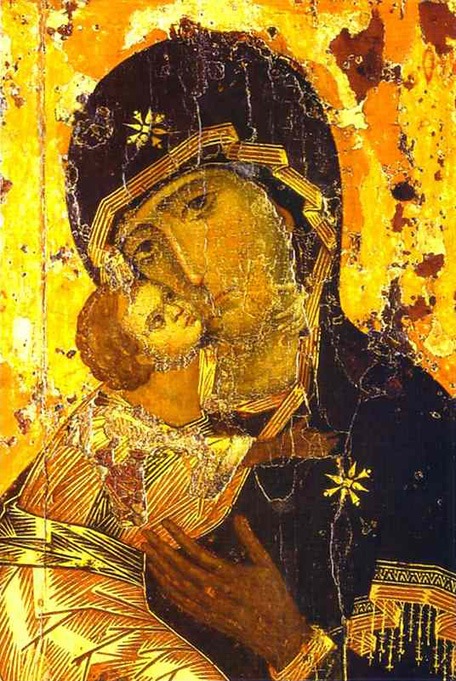

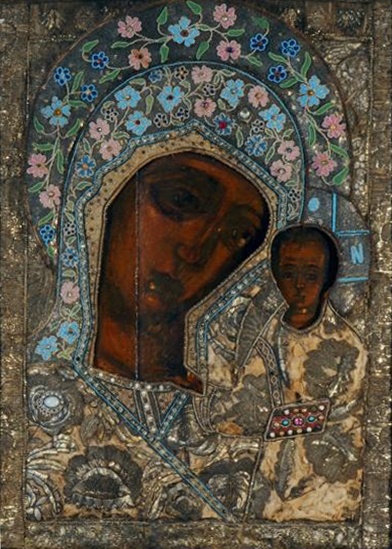

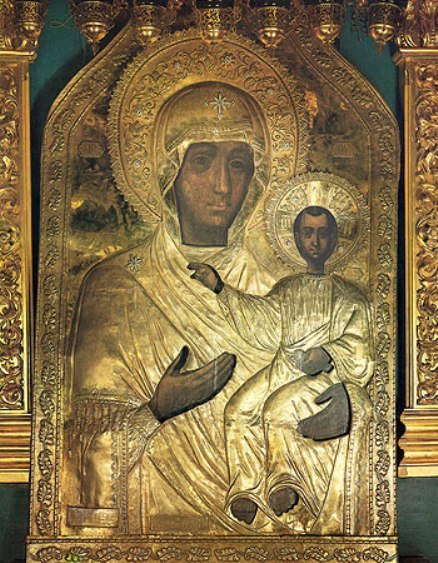

DK: Well, really, what I would say, I identify most as is Orthodox. But I say this, and I don’t really feel that I am properly equipped to wade too deep into discussions about the various denominations. Some things, sure. Episcopalianism for example, where you have openly gay priests performing same sex marriages – this is clearly not a part of the larger family that we’re talking about here.

You’ve got to remember, I wasn’t raised to be too much of a Christian; it was something I fell into, quite literally, in my twenties, after trying all sorts of tragic, misguided attempts to find God. It got to the point where I’d tried so many different things and I found myself in a very dark place spiritually, a place I couldn’t think or reason my way out of; and I just instinctively said, “I’m sorry.”

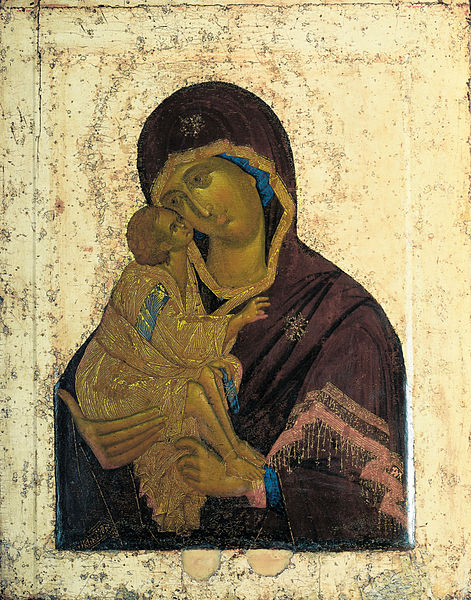

And I started saying this over and over in my head: “Jesus, I’m sorry, and I love you.” Looping it over and over again. I later realized that this was very similar to the Orthodox heart prayer, which is really what drew me to that particular expression of the faith along with these other elements, liturgy, the icons, which I find to be so mystical and moving.

So, I’m relatively young in my walk with this thing. I’ve read the “good book” cover to cover twice now. But I’m not there yet, the basic level of scriptural literacy which was once a basic expectation for respectable men. I have a lot of younger men who follow me that really are much further along in that walk than I am, and I rely on their council quite a bit.

Your question here is really so specialized, I want to make clear too that I give the Catholics respect, and I know many, many great Catholics. Some great Catholic Latinos as well, who I find very easy to relate to. Look, they get laughed at for contraception. But, really, looking back, we can see that they were exactly correct.

Contraception was the beginning of a wedging between the act of sexuality and the consequence of reproduction, a wedge which the Satanic Left has used to now pry the things so far apart, where we recognize same sex unions, where reproduction is fundamentally impossible to marriage. A big winner for me with the zoomers is my Federal ban on pornography, which really should be a no brainer for any sexually normal person.

If for no other reason than its association with sex trafficking. I mean, look, get a new hobby people. Go outside and meet someone. I don’t know. (Laughs). Now, do I call for a federal ban on contraception? I’m not sure, probably not. But I think that we can really look at what this stuff has led to and use it to really re-imagine nationally how we engage with birth control.

What are our objectives with this stuff? Let’s engage with this stuff in a manner which steers the American people back in the right direction, which is limiting sexual partners, sexuality in general prior to marriage and working to rebuild the family.

So, really on this topic, and I know my answer is weak here because I’m not actually as familiar with these ideological struggles as you assume that I am – but, look, there are people of strong Christian Faith in most of these groups and I want to encourage that. There are also many, many more lukewarm Christians floating around as well. Prosperity gospel nonsense. It appears to be spreading to varying degrees in all of the denominations.

My biggest concern isn’t so much your denomination, it’s your motivation. What are you looking for from your Faith? For me, especially for men, it has got to be about challenging yourself, critiquing yourself. If you’re using it to excuse yourself, to pat yourself on the back, that’s really what’s of concern to me. For women, perhaps, a little Joel Osteen, a little encouragement can be nice. But, as men, really, I need guys that are getting up every day and fighting internally, preparing for the external struggle. That’s really my contribution on this topic.

GC: A word about foreign policy. Some time ago, President Trump reportedly considered the possibility to invade Venezuela. Would you welcome such an operation? In regards to the Iranian regime of the Mullahs, how do you assess the option of invading Iran and restoring the Shah’s heir as the head of that country?

DK: I know there’s a lot of hubbub about fighting other people’s wars, and I certainly understand that. And, you know, of course, military conflict should always be approached with due diligence. But I’m going to be clear on this. I am no isolationist. I believe in leadership; and I look at what is happening, particularly in Europe, from a cultural perspective; and I am not OK with that. Europe is far too important culturally and historically to our world to simply be allowed to sink and disappear.

On a global scale, I intend to be extremely proactive in terms of pushing our values and ideals. It’s our responsibility as the super-power of the world to step up and lead when we see what is occurring. Where you’ll find my leadership to be very different from the Neocons of the past is what my values are. I think the big, fatal flaw of what has been American Imperialism is the place where it’s coming from.

For half-a-century, we’ve operated under the premise that the “good news” that Western civilization had to spread to the rest of the world was democracy and capitalism. That may be a fruit of the good news. But the “good news” I’ll be looking to export to the rest of the World is the Gospel of Jesus Christ, which is the foundational pre-requisite for enjoying so many of these wonderful things, free trade, etc. What we’re seeing now in our nations is that they don’t work so well without that foundation.

Democracy works great perhaps when you have a nation of ethical Christians. But how quickly does that blessing become a curse when you have a nation of heathens?

So, for me, when I look out into the world and we start talking about the true threats to Western Civilization – and I’ve said this before, Iranian Ayatollah Khamenei is far less concerning to me than London Mayor Sadiq Khan, as an example. Let’s start with the enemies within. But let’s also not pretend that a resurgent Ottoman Empire is a good thing, either.

Geopolitically, we need to reshape the whole thing. I think a lot about moving away from the E.U. and starting a totally new league of Patriarchal Christian nations. To start exerting pressure there. First on these European nations, who are quite literally selling their people into their graves.

There are a lot of other topics on the horizon as well, such as, Artificial Intelligence where, I think, we want to start working together, leading with other nations, a lot of whom are Eastern European, to start putting this thing back together, back into place.

Technologies, like designer baby stuff and all of that crazy stuff. Look, there are free market forces which, if unchecked, will launch these deeply demonic realities into our world. I don’t ever want parents, whether they are American, British or Chinese to have to choose between having the child God intended for them and one that can effectively compete for an adequate quality of life.

Russia to me is a natural ally in so much of what we’re about; and, of course, we see great things from nations like Poland and Hungary as well – versus places like France and Germany, where leadership has just been appalling. But I don’t want to turn my back on the good people in those nations, either. In fact, I won’t. I think a lot about that 3rd of France that voted for Marine Le Pen. God bless them.

That’s a lot of Patriots living in a crumbling country, without a government that gives a damn about their future. They need and deserve our help; and if their governments won’t stand up for them, I think it falls to us, as the leaders of the free world – the Christian world – to do it for them.

I’m not talking necessarily about military intervention here, but sanctions, financial pressure. This is where I want to be focusing this stuff initially. Once we unite our own world, I think, the barbarians at the gates become much easier to confront, dismantle and defeat.

Christian Authority is “plug and play” for Western Nations and is, far and away, the most efficient, effective and humane way to get our shared civilization off of this trajectory towards death. It’s funny, because I get asked about a lot about current events, and I’m often pretty out of the loop. I was extremely into politics when I was in Middle School and High School, and I think, and not wanting to sound arrogant, but I reached a point where I felt I pretty much understood all of the various dynamics at play and really stepped back; haven’t looked at it as much since because, really, it’s all been rather easily predictable. Not specifics like election outcomes, but the general thing which is occurring, which is that we are, I feel, inevitably heading into authority, as a result of this rather tremendous, rampant social chaos which we’re drowning in.

The question is who is going to get there first. I think, objectively, we have to step back and realize that the Left is much, much closer to realizing that destiny. Look, the two sides are not going to be reconciled. The side which gets there first, they’re going to win. It’s a bit of a cat-and-mouse thing. If this coalition of people, who used to be understood as the American people, but who are now one of two parties and represent a base which is dwindling – if they, we, don’t step up, rise to meet this thing, get there first, they’re toast.

That’s why my shot here is 2024. That’s the earliest I can go for it. It’s too urgent. I can’t wait. we can’t wait, if I’m an odds maker. Look, the Left is basically an election away from sealing this thing up. But there’s something in the air, something about the look in our eyes. I like our chances – and I sure as heck would not bet against us.

The image shows, “Christ in Majesty” by Jan Henryk de Rosen, completed in 1958, in the apse of the Great Upper Church, in the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception.