Behind a burning red fog The great mind swims in confusion Its blood ferments in anger Honor and wisdom will cower Your river's flow is damned all to hell Your river's flow is damned all to hell Drifting in a current to stagnate Encircle the vision of rust Your river's flow is damned all to hell Your river's flow is damned all to hell Strong hearts soar through blindness Tearing the fog, tearing the eyes To clarity To a place where truth is seen Your shell is hollow, your shell is hollow, so am I The rest will follow, the rest will follow, so will I So will I (Neurosis, “Under the Surface”) “Your will be done, on earth as in heaven” (Mt 6:10) Lead me, Lord, in the path of your commandments. Teach me the demands of your precepts and I will keep them to the end. Train me to observe your law, to keep it with my heart. Guide me in the path of your commands; for there is my delight. Bend my heart to your will and not to love of gain. Keep my eyes from what is false; by your word, give me life. Keep the promise you have made to the servant who fears you. Keep me from the scorn I dread, for your decrees are good. See, I long for your precepts; then in your justice, give me life. (Psalm 118)

There are only two paths in life, the one that leads to heaven and the one that leads to hell. And there are only two modes of living, salvation and well-being. One must live in the mode of salvation to end up in heaven, and the mode of well-being can only lead to hell. Heaven begins on earth when one pursues salvation, and hell is right here for those who pursue well-being. One cannot live in both modes, as they are mutually exclusive, though one can live in one and then another. It is the mode that one persists in unto the end that determines eternity. It is not that well-being is hell per se, for it is a good, though not the ultimate one, and the fruit of living the mode of salvation is true well-being in this life, the most that is possible on earth, a life of sometimes agonizing and unspeakable suffering, surely, but also ineffable peace, supernal joy, and indomitable hope. Living in God’s Divine Will is heaven itself, and it begins now. And it culminates in eternity with the most well-being possible to a creature, complete union with God. So, well-being is good, but if we seek it and not God as our main goal in this life, if it is our primary existential mode, with salvation taking a back seat, we obtain neither well-being nor salvation.

What exactly do I mean by salvation and well-being, and why are they mutually exclusive? In a fascinating 1970s book entitled, Marriage: Dead or Alive, the twentieth-century Swiss Jungian psychiatrist Adolf Guggenbühl-Craig explained that marriage was failing more than ever before because it was mistakenly portrayed and understood in the mode of well-being, where in truth it is a relationship and institution grounded in and ordered to salvation, only succeeding when understood and lived out as such. About well-being vs salvation, he writes:

Clearly not belonging to the state of well-being are tensions, dissatisfactions, painful emotions, anxiety, hatred, difficult and insoluble internal and external conflicts, obsessive searching for an undiscoverable truth, confused struggles about God, and the felt need to come to terms with evil and death. Sickness most certainly does not belong to the state of well-being. It is much easier, at any rate, for physically and psychologically healthy people to enjoy a sense of well-being than it is for the sick. “Give us our daily bread” really implies, “Give us daily our sense of well-being.”. . . As goals, salvation and well-being contradict each other. The path to happiness does not necessarily include suffering. For the sake of our well-being, we are urged to be happy and not to break our heads with questions that have no answer. A happy person sits at the family table among loved ones and enjoys a hearty meal. A person who seeks salvation wrestles with God, the Devil, and the world, and confronts death, even if all of this is not absolutely necessary at that precise moment.

The mode of salvation was modeled perfectly for us in the life of Jesus Christ, and it is only by following His model that we can attain our soul’s salvation, but it is not that the salvation mode of life only became known to us by the Incarnation. It was known to the ancient Jews as well as the pagans, and it is known to today’s Jews, Muslims, pagans, and secular humanists, for it is a fundamental part of natural human consciousness. Those who prefer this mode over the mode of well-being, and live it unto the end, are saved, regardless of what they know or do not know about Jesus Christ, unless, of course, they reject Him knowingly and deliberately. But if they are truly living within the mode of salvation, they will never do that. When Jesus comes to them three times before they die, as St. Faustina said He would, they will recognize Him as the unknown Someone they were looking for, and the reason they rejected the mode of well-being for the much less comfortable mode of salvation.

A good pagan example of the two modes in contrast is found in the two heroes of Homer’s epics, Achilles and Odysseus. Achilles is given a choice to live a long life of well-being or a short life of salvation. The mode of salvation for the warrior was a life of valor on the battlefield, seeking honor and glory more than the mere preservation of one’s life. Achilles fulfilled this mode excellently until he was deprived of the honor he deserved by King Agamemnon. Achilles reacted with a superhuman rage and offense at this affront, and this not mainly because his war-trophy bride, Briseis, was taken from him, but more because he was destined before birth to have been the new Zeus, but was deprived of this by Zeus himself. According to a Pindaric tradition, Thetis, at the behest of Zeus, acceded to marriage with the mortal Peleus instead of Zeus in order to avert the birth of a son who would be stronger than his father. Achilles would have surpassed Zeus if his mother had not consented to a marriage beneath her divine status that neutralized the threat he constituted to Zeus’s order. Achilles knew this, and so harbored in the recesses of his soul an infinite desire for divine power and glory that could never be satisfied, as well as an infinite divine rage at this existential frustration. This is an excellent image of the desire all humans have for divinization, along with the nagging sense that we were all destined for greatness but somehow lost it, and the ineradicable feeling of futility, dissatisfaction, and guilt with a mere life of well-being. Until Jesus came, we had no real ground for hope that our infinite longings could ever be fulfilled, yet some before Christ, such as faithful Hebrews and noble pagans, still chose to live in the mode of salvation, somehow knowing they were obliged to do so even without a grounded hope in an eventual successful end. Getting back to Achilles, when he was dishonored by Agamemnon, a mere mortal, it was as if his whole raison d’etre was destroyed, and he chose to leave the battle and live the mode of well-being in his tent, hanging out with his friends and playing music. When some of the Greek leaders come to his tent to try to convince him to rejoin the battle, Achilles says:

Neither Agamemnon nor any other Greek will change my mind, for it seems there is no gratitude for ceaseless battle with our enemies. He who fights his best and he who stays away earn the same reward, the coward and the brave man win like honor, death comes alike to the idler and to him who toils. No profit to me from my sufferings, endlessly risking my life in war.

Here Achilles reveals the mode of well-being he has recently adopted, with its irrefutable logic of the futility of a life pursuing salvation. For those living at the time of the Trojan War, 1200 BC or so, the afterlife in the underworld was a shadowy thing, neither punishment nor reward but a flittering, ghostlike, and passionless existence, barely alive, with no drama or purpose. In the Odyssey, Odysseus meets Achilles in the underworld and is told by him that it is so lame that it is better to be a slave on the earth than to rule Hades, in other words, that there is no reason to pursue the life of salvation. But somehow, in spite of the nihilistic yet airtight well-being logic he entertains for a moment—what good is it to be a warrior if in death all are equal, and equally half-dead?—Achilles knows that a life of honor and courage and death-defying valor is obligatory for him and that it violates a primordial, cosmic law for him to allow his fellow Greeks to die dishonorably, and so when his best friend Patroclus dies in battle due to his wallowing in well-being despair, he re-establishes himself in salvation mode and kicks much Trojan ass with some bedecked and armed with god-designed armor and a cosmos-wrought shield that contains the whole cosmos, signifying that the way of salvation, and not the way of well-being, is written into the very fabric of things. And he dies soon after by getting shot by an arrow in his heel.

Odysseus lived the salvation mode until, on his way home from Troy, he is waylayed by a nymph goddess, Calypso, who “traps” him on her island for seven years. I put trap in scare quotes because in the less-literal yet more accurate reading, Odysseus was free to leave anytime he wanted, and it was just the case that he did not want to, as he now had a matchless goddess as a very willing wife, one who also shared her immortality with him. But her name means “she who conceals,” and the price he had to pay for his well-being on steroids was never again to be seen and known, and perhaps to have his life up till then never sung by bards to the future generations of Greeks. Somehow he knew (when he got the seven-year itch) that risking abominable suffering in unknown waters populated by horrendous monsters with a very uncertain prospect of ever getting home alive was worth more than an eternity of perfect, earthly well-being. So he put on the helmet of salvation, as it were, built a raft, and eventually sang his own song on the island of the Phaecians, a paradisal mecca of well-being whose king also invited him to renounce his salvation, marry his beautiful daughter, and stay forever with them before sailing him (almost) home on a magic ship.

My last example from the ancient world is Job. According to the theology of his day, which was probably after the Flood but well before Moses, those who followed God’s law were blessed with a life of well-being, and this was a reason as good as any other to do so. If one did not experience well-being—health, long life, wealth, and a big family with lots of land and flocks—it meant that one was not following God too well, and deserved not to have it. But this was a mistaken notion of the economy of God and the true purpose for following Him, as Job was to discover. Satan challenged God by saying, essentially: “The only reason anyone ‘loves’ you and doesn’t curse you is because you reward them with well-being. Take away their well-being, and see what happens. You talk about salvation all the time. Well, they never really choose it, if it even exists. There is only well-being disguised as salvation.” God takes away all the well-being from Job, and his counselors tell him to repent of his sin. They are firmly in the well-being mode. Perhaps Job was as well at some time or another, but he meditated for a while on the dung heap, and he was now in salvation mode, as he cried, “I know my redeemer lives.” How did he know that? Everyone in the salvation mode knows it, for it is somehow knowing it that puts one into that mode. He eventually was given his well-being back, just as Jesus was resurrected, but an intimate meeting with the unknowable God was what he wanted all along, and he got it, in a terrifying whirlwind cross-examination that almost killed him. He didn’t get a comprehensible and satisfying answer to the mystery of suffering, as the mode of well-being would expect. What he got was confirmation that salvation is not at all about human well-being or the lack of it, or even being just or unjust or pious or impious. It’s something way beyond even morality, however essential that is. It’s about God, period. As St. Louis de Montfort often said: “God alone.”

Why not just call these modes religious or non-religious, or even Christian or non-Christian? It is because those who practice religion and identify as such are not necessarily living the mode of salvation, and those who say they are not religious are not necessarily living the mode of well-being. People can say they believe in God and actually practice worship and seem to live for Him while living completely or mainly in the mode of well-being, and people can say that they don’t believe or care about God or spiritual matters, and appear not to, while living completely or mainly in the salvation mode. It seems to me that the well-being/salvation modes are more fundamental and definitive than the religious/non-religious labels, or even the self-identification of Christian or non-Christian. For, they are existential and primary, residing and operating in the deepest recesses of the heart and the will. Before we consciously choose to act at any specific time in any particular way, we have always-already chosen, as it were, one of these modes, and our choices from then on are derivative from and caused by that primordial choice. Why we choose one mode or the other and persist in it is ultimately a mystery, but I would still like to say something about it later on.

We live within a global culture of well-being, an elite-imposed and artificial, totalitarian therapeutic prison, and this means that through an inexorable, ineluctable, and inescapable cultural conditioning process, well-being is the default position of the collective consciousness. Charles Taylor calls it the Immanent Frame. We are meant by our puppeteer conditioners to know of nothing other. If we do not deliberately fight to resist and escape this conditioning, it will mold and poison our souls unconsciously. But even if we somehow become acquainted while within this prison with the salvific mode of consciousness, through, say, encountering traditional religion or reading classic literature or meeting a living saint, we are programmed to translate this experience into the discourse, grammar, and social-imaginary of well-being, thereby turning it into its opposite.

If the reader is still wondering what exactly the modes of well-being and salvation are, that’s ok, for I am as well. It’s not possible to nail them down in precise language. They are too big and deep for language. The particular mode of thought, cast of concepts, and exigency of language we happen now to understand and employ derives from and is constituted by one of these modes or the other. There is no third. If we are in the mode of well-being, we see the world that way, and we will not only not understand the mode of salvation, we will despise it. Furthermore, we will not even recognize that we are in a mode at all—it is just the way things are. One has to be in the mode of salvation to understand that experiential modes even exist, and then to understand the nature of each mode and their radical opposition. For, these two modes determine exhaustively the very contours of the meaning of life itself, as they are the earthly images of the two modes of eternity. Thus, it must not be expected that they can be discretely and definitively defined in this life. They can be described, pointed to, adumbrated, suggested, intuited, exemplified, metaphorized, allegorized, unveiled, demarcated, translated, and cartographed—but never exhaustively grasped. It is these modes, after all, that define us. Nevertheless, I intend to keep describing and attempting to define them as we proceed, hopefully with increasing lucidity.

This is the clearest definition I can think of at the moment: The mode of well-being is a living hell that leads to eternal hell. The mode of salvation is a living heaven that leads to eternal heaven. And here is the most compelling reason I can think of why this is the case: Hell is the choice for the complete absence of God, Who is ultimate reality. Hell is thus the choice for ultimate unreality. Thus, the mode of well-being chosen in this life is a life of perpetual and absolute war with ultimate reality.

Perhaps an example will be helpful. The plandemic of 2020 was a test, a trial run for the Final Judgment deciding the eternity of every human being ever to live, either Heaven or Hell. What was placed before every human being was a stark existential and theological choice, a choice that was also a judgment. For those for whom this trial would be the manifestation and confirmation of their prior existential choice for well-being, or for those for whom it would be the uber-choice of their preferred long-term state, it seemed no choice at all. I mean, there was a deadly virus, you know, the deadliest one, and all you needed to do to avoid your own sickness or death and prevent the sickness and death of others was to do what you were told to do by those authorized to protect you from sickness and death. If you did that, I mean, the curve would be flattened, man. They told you to allow certain others to stick a swab in your nose, wear a mask all day, stay six feet away from other people, stay home, and close your business or school or church. They were so loving and committed to your health that they coerced these directives, rewarding you if you obeyed them and punishing you if you did not. They told you to get the vaccine or else you would most probably die and kill others, and they helped you to make the right choice by making sure that your life would be a living hell if you refused the shot. Choice? What the hell are you talking about?

The problem is that if you chose to do what they told you, you were not choosing to protect yourself and others from a deadly virus, but you were choosing hell. Now, there were some who were genuinely invincibly ignorant to the lies they were believing, at least at first, and so not culpable. But in the weeks and months after, as reality reasserted itself, it became impossible to believe the lies without fault. You were choosing hell because you were choosing unreality, and knowingly so. By choosing to obey these arbitrary and irrational prescriptions—and you knew, didn’t you? that they were arbitrary and irrational—you were choosing to believe in the Big Lie that underlay them, namely, that healthy people with no symptoms of illness are contagious. You, of course, knew this to be untrue. This is a lie, and an insane one. And you knew it was an insane lie, but you believed it anyway and acted accordingly. And you were quite proud of your mendacious insanity. You believed this insane lie because it made you feel good, in both the pleasurable and moral meaning of the word, but in doing so you put yourself under false authority. And you knew that it was false authority, because what they prescribed was all predicated on a manifest lie, and you knew it was a lie. No one thinks that healthy people with no symptoms are contagious, not even you. But you thought it anyway. “Just wear the f$%*in mask”—the first commandment of Hell. You obeyed this commandment with diabolical pleasure and took the same pleasure in torturing those who disobeyed it. Now, not everyone behaved this maliciously, and I am describing the extreme covidiot here, but all of us to some extent participated in this treasonous behavior.

Is putting oneself under false authority really so bad? Yes, it is the worst sin possible. It is the sin against the Holy Spirit, which Jesus said is unforgivable. It is calling good evil and evil good. Salvation comes from putting oneself under the authority of Truth, Who is Jesus Christ, the Son of the Father, Who was with God in the beginning and is God. Damnation comes from putting yourself under the authority of untruth, whose father is Satan, the father of lies, who was a liar and murderer from the beginning. And it is this that distinguishes the mode of well-being from the mode of salvation. In well-being, one puts truth second to everything else. Truth is never first. Perhaps it is an authority, but it is never the authority. In salvation, truth is always first. It is Authority, period. One strives for well-being, for we are permitted to do so, but it is always a striving for well-being in the light of and under the authority of truth. And if believing in and obeying the truth means that one’s earthly well-being is sacrificed, then so be it. Salvation comes first. Salvation means eternal well-being, which is all that matters. Earthly well-being is a good, and those who live in the mode of salvation obtain it in its essence, which is joy and peace in union with God in this life, which no one can take away. Sometimes this joy and peace are accompanied by worldly goods, such as financial prosperity and bodily health and good reputation. But sometimes not. And it doesn’t matter one way or the other for the salvation-minded. Obedience to truth is all that matters. For the well-being-minded, a feeling of well-being is all that matters, and knowing and obeying truth is, at best, only a means to this highest end.

I mentioned earlier, and it bears repeating, that “We live within a global culture of well-being, an elite-imposed and artificial, totalitarian therapeutic prison, and this means that through an inexorable, ineluctable, and inescapable cultural conditioning process, well-being is the default position of the collective consciousness.” And this includes those, whether traditional Catholic, fundamentalist Christian, Koranic mystic, alt-right groyper, paleocon-bearded hipster, dark web gnostic, or perennialist blackpiller, all of which would seem quite immune to such conditioning and who would certainly, it seems, reject the default position. I have news for you: not necessarily. The mode of well-being has been firmly in place in the West for centuries, and it has been getting ever more well-being-ish ever since, exponentially since the year 2020. Medieval Christendom was a culture of salvation. Well-being as a legitimate mode of life didn’t exist. People sinned, of course, by choosing for well-being against salvation, but they were ashamed of it, and society let them know. Modernity, on the other hand, is a culture of well-being as The Good, a culture in which the mode of salvation is utterly shameful.

The Catholic Church is the mode of salvation on Earth, for it is the mystical body of the Incarnate Savior. If this mode existed in cultures before Christ and His Church, it was solely due to His providential grace in anticipation of and preparation for His Church, the soul and lifeblood of the world with its various cultures. At the present moment, the human infrastructure and clerical personnel of the Church, in league with her unbaptized external enemies, are at war with her divine core, and Satan is in control of the majority of the clerical human personnel and all of her external enemies. Satan’s hegemony over the Church and thus the world has been building since the 1900s but really in earnest after 1962. Leo XIII and Our Ladies of Akita and Fatima had prophesized it and told us what to do to prevent it, but most didn’t listen.

What this means is that there has never been a time in the history of the human race in which the mode of salvation has been more eclipsed and difficult to live out, and the mode of well-being more pronounced, seductive, irresistible, ubiquitous, and easy to practice, than today. One might think of the time before Christ as comparable or even worse than now, but consider that the corruption of the best is the worst, that nothing could be worse than a counterfeit of salvation replacing the true one, and such could only be possible after the historical manifestation of the full salvific truth of Jesus Christ. What we have today is much worse than paganism, and much worse than even the most corrupt and “dark” of post-Incarnation ages of years past. What we have is a culture of well-being that wears the mask of salvation, with the salvation mode practically counterfeited out of existence. Even the best of the salvation-mode sub-cultures are more or less compromised and tainted by the ubiquitous well-being culture, and they easily end up becoming mirror images of it, appearing to be solidly salvific but surreptitiously and subtly counterfeit. They talk salvation but walk well-being.

This is all I've known A way to be True to all All that inspires A torch in a black sea Our stones still stand To remind us of loss A loss mirrored on our souls A watchfire brings strength Breathe in the heat In the eternal path Armoured against life (Neurosis, "Watchfire")

Human beings were created by God for happiness in the worship of God. For reasons entirely inscrutable to human beings (all of the best reasons that have been offered cannot adequately explain it), God decided to make this happiness a personal choice for which we are responsible. This means that humans can choose not to worship God, that is, choose unhappiness over happiness. Why would a human being choose unhappiness and reject the very reason he was created? No one knows the answer to this question, for it is a mystery, the unfathomable and inscrutable mystery of evil. All we know is that we cannot escape this choice. Whether we obtain eternal happiness in the worship of God or eternal unhappiness in the refusal of this worship is entirely up to us, and any of us is capable of choosing against his own happiness. If you end up in hell for all eternity, it is because you wanted while alive and want now to be there. You refused to worship God, and you did so knowing it would mean eternal hell, and you chose it anyway. Think this is impossible? Think that God would and could never allow anyone to suffer eternal separation from Him? Well, have fun hanging out with know-it-all spiritual morons like David Bentley Hart and engage in gnostic spiritual masturbation, but just know that the Hell you deny awaits you if you persist in rejecting truth.

What does the choice for hell look like? The Catholic Church teaches us that if we die in a state of unrepentance, in a state of mortal sin, we go to hell. What is it to commit a mortal sin, and what does a state of unrepentance look like? Jesus said, “You shall know the truth, and the truth shall set you free,” and “I am the way, the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.” At its core, mortal sin is the refusal to know and obey truth, which is to say, to reject reality, for truth is the conformity of our souls with reality. At the core of reality is the Good, which is reality qua desirable. And since Jesus Christ is the truth, reality incarnate, then every refusal of reality, refusal to know and obey truth, is a rejection of Jesus, the Incarnate Good. Unrepentance means that we persist up to the moment of death in this rejection in the knowledge that we are choosing hell because of it. We end in up hell if we persist in our rejection of reality, truth, and Jesus Christ.

Why would anyone reject reality and truth and the Good and Jesus Christ? The obvious answer is due to a mistake. For whatever reason, we are not in a right relationship with reality and so misunderstand the truth about it. We reject what we do not know is truth. This is certainly possible, but why do we not know the truth? We are personally responsible for the relationship we have with reality when we die, and if it is not a right one, it is ultimately our fault. Not knowing something is the truth at one time or another can certainly be the fault of someone else whom we depend on for knowing what is true, such as a parent or a teacher or a culture, but this is a temporary and remediable situation. The injustice done to our souls by false authorities may not be our fault, but we have the ability and responsibility to rectify this injustice. Even though it is the case that reality is mediated to us by human authorities that could be mistaken or lying about the truth, and mediated by our own faculties of knowing that might be, due to ourselves or others, damaged or faulty, this does not excuse us from the personal responsibility of doing all we can to ensure that we are in a correct relationship with reality and thus know what is true. And we have the responsibility of not only knowing what is true, but also loving and obeying it. If we did not have this responsibility, hell would not exist, for we would always have a legitimate excuse that renders us not personally responsible for our not knowing and not loving truth. There would be no real guilt.

How do we overcome the damage done to our souls by others and ourselves that has caused us, right now, not to be in a right relationship with reality and thus not to know or love what is true? If we are dependent on others for knowing certain truths, and even for the development in us, especially when we are young, of the habit of being docile to truth, how do we overcome this dependency when it has led us into a soul-state of untruth? The answer is that we are always able to choose between well-being, in which truth isn’t a priority, and salvation, where it is the only priority, regardless of how badly we might have been damaged. Indeed, if we had always chosen salvation over well-being, we would not be damaged right now in the first place, for when in a state of salvation, we are immune to the damage done to our souls by the truth-treason of others. The problem is, of course, that we were not and are not now fully in a state of salvation, and so have been damaged. But we can begin to undo this damage by choosing, right now, to be in the salvation mode, and we can keep choosing until the moment we die.

Consider the situation of a Pharisee at the time of Christ. He was badly damaged by the Jewish culture in which he was raised, for it was thoroughly corrupt, even though it was given to the Jews by God Himself. Jesus gives a very clear picture of this culture:

But woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you lock people out of the kingdom of heaven. For you do not go in yourselves, and when others are going in, you stop them. Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you cross sea and land to make a single convert, and you make the new convert twice as much a child of hell as yourselves.

Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you clean the outside of the cup and of the plate, but inside they are full of greed and self-indulgence. You blind Pharisee! First clean the inside of the cup, so that the outside also may become clean. . . . Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you are like whitewashed tombs, which on the outside look beautiful, but inside they are full of the bones of the dead and of all kinds of filth. So you also on the outside look righteous to others, but inside you are full of hypocrisy and lawlessness.

Imagine being raised as a Pharisee in this culture. It was now a culture of well-being, not salvation, due to the Jewish leaders’ treason against God. No Pharisee was forced to participate in this corrupt culture, for he still had access to uncorrupted scriptures and traditions. He could have resisted the corruption and even called it out, as Jesus did, but this would have required consistently being in and acting from the mode of salvation, which would have been quite difficult with all the pressure to and rewards from being in the mode of well-being masking as the mode of salvation. Who was modeling it for them? No one. It was the opposite. Everyone was modeling Satan, whom Jesus called their father. But Jesus, the perfect embodiment of the uncorrupted scriptures and tradition, was now present in their midst; now they had a model and thus the ability to compare themselves to the Good and see and repent of their evil. He made their evil quite clear to them, and there was no reason not to believe Him, for He had no hypocrisy in Him, and He spoke to them in love and from the mode of salvation. Perhaps before Jesus came they had some excuse for their evil, but not now.

All a Pharisee had to do was to pose one question to himself: “Is He the evil one, or is it I?” This is a question anyone at any time can ask, and it is a question evoked by the existential mode of salvation, a mode anyone at any time can adopt in the deepest recesses of his soul. Saul became Paul when he adopted this mode and asked this question, a question prompted by a shocking mystical encounter with the Risen Lord that knocked him to the ground and left him physically blind. God will always provide the precise experiences we need to get into the salvation mode and begin asking salvific questions, but only if we first desire to exist in the mode by which such questions will be salvific. Saul must have desired this in the core of his being, and Jesus saw this and helped him to fulfill it. Jesus knew how evil was the culture that produced Saul the Christ-hating Pharisee, and He provided him a way out. Of course, the desire and ability to live in the salvific mode is itself a gift of God unmerited by us without which we could never be saved. But it is always offered and made available to us. We must simply choose it.

A good culture is one that forms its denizens to be in a right relationship to reality, causing the mind to know it and the will to love it. A good culture makes it easier to know and love truth, and a bad culture makes it harder. The Pharisee culture of the Jews in Saul’s day was a bad culture, for it disposed its leaders to reject Jesus Christ. The rejection of Jesus Christ is at the very heart of Western culture in our day, and has been so for a long time, though harder to recognize in past centuries. Our present culture makes it very easy not to know and love truth, for it makes it all but impossible and undesirable to ask questions from the mode of salvation, especially this question: “Is it true?” It thus makes it very easy to be, live, and act in the mode of well-being while thinking one is in the mode of salvation, or not even knowing that there is any other mode than well-being, or that one is in any “mode” at all. How can we be saved from this most perilous deception? Alasdair MacIntyre:

We have within our social order few if any social milieus within which reflective and critical enquiry concerning the central issues of human life can be sustained…. This tends to be a culture of answers, not of questions, and those answers, whether secular or religious, liberal or conservative, are generally delivered as though meant to put an end to questioning.

Paul Evdokimov:

The outdated religious person and the modern sophisticated irreligious individual meet back to back in an immanence imprisoned within itself…. The denial of God has thus permitted the affirmation of man. Once this affirmation is effected, there is no longer anything to be denied or subordinated… On this level total man will not be able to ask any questions concerning his own reality, just as God does not put a question to himself

The totalitarians ruling us are satanists, whether officially or not, and they want to abuse us to such an extent that we no longer ask questions in the mode of salvation in obedience to the ultimate authority of Truth and thereby save our souls. Asking questions indicates a soul that is aware of her dignity as a responsible creature, personally responsible to know and obey the authority of truth, not human counterfeits of it. The satanists want us to degrade ourselves by choosing idols over God, and they want us to do so knowingly and deliberately. This is why they hate questions more than anything. Ultimately, they want us to feel we are so worthless and stupid and deserving of nothing but abuse and death that we voluntarily murder ourselves. They’d rather we do it to ourselves, for it would mean more souls in hell. The first step to obtaining their goal is to get us to stop asking questions and caring about the Truth. God is the answer to all questions. They want us to see them as God. If we stop asking questions about the claims and actions of any human being, we are obeying their satanic command. Origen once wrote: “Every true question is like the lance which pierces the side of Christ causing blood and water to flow forth.” It is the blood and water that saved the Centurion, and it will save us if we so desire it. All we need to do is continually ask ourselves these questions: “Is it true? Am I pursuing salvation right now, or well-being?” And God will do the rest.

O divine Redeemer! As a victim of love for the Church and souls, I surrender myself to you and abandon myself to you! Please, I pray, accept favorably my offering, and I will be happy and confident. Alas! It is very little, I know, but I have nothing more, and I give you everything. I love my poverty and weakness because they bring me all your mercy and your most tender concerns. My God, you know my fragility and the bottomless abyss of my misery… If I were ever to be unfaithful to your sovereign will for me; if I were to shrink back from suffering and the cross and desert your sweet path by fleeing the tender support of your arms, oh! I beg and implore you, grant me the grace to die instantly. Hear me, O most loving Heart of my God, hear me by your sweetest name of Jesus, by the love of your Most Holy Mother, by the intercession of Saint Joseph, Saint John the beloved, and all the other saints, and by your divine ardor to fulfill in all things the will of your Father. (Servant of God Marthe Robin).

Thaddeus Kozinski teaches philosophy and humanities at Memoria College. His latest books are Modernity as Apocalypse: Sacred Nihilism and the Counterfeits of Logos, and Words, Concepts, Reality: Aristotelian Logic for Teenagers. He writes here.

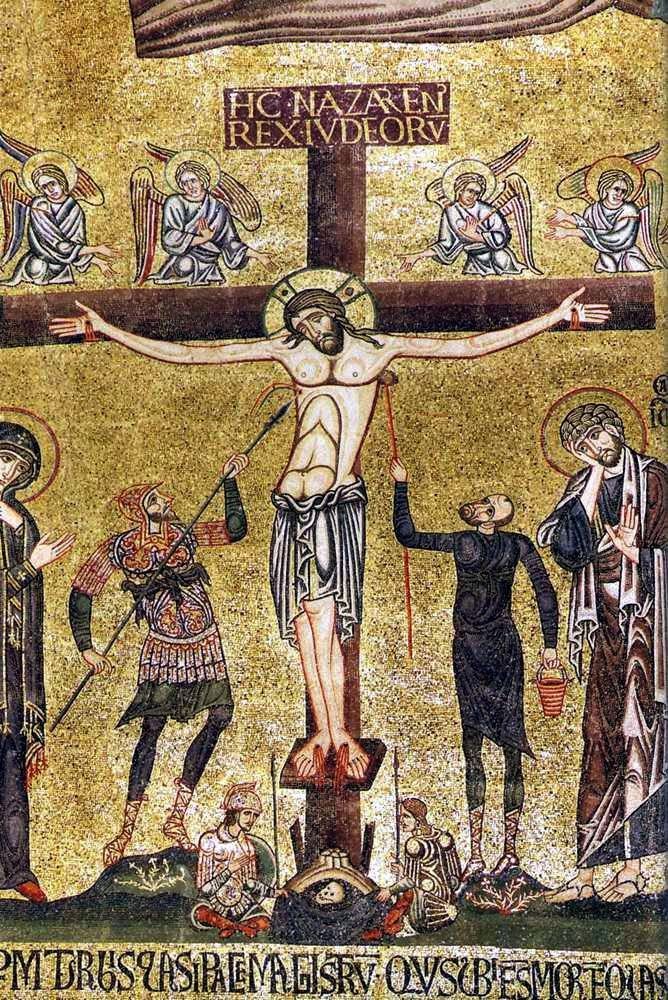

Featured: Crucifixion, Basilica di San Marco, Venice, ca., 1200.