I.

Introduction

Europe’s Christian identity has been a fundamental component of its history and culture, shaping not only the religious sphere but also politics, morals and way of life. This article sets out to examine the multiple layers of Christian identity in Europe, highlighting its historical roots, influences over time, and how it faces the challenges of an increasingly pluralistic and secular society.

By Way of Prologue…

Two immense interconnected problems haunt us with alarming urgency. The birth rate of this Europe of ours, which is slowly aging and dying without replacement, without a sufficient replacement rate; and the key to immigration, which responds to the fact that there is no one to take on certain jobs in our society.

Much more depends on how both are dealt with than we think. There is an almost threatening perspective of survival of a certain culture, the European one. Of a whole wealth contributed to the human family that is in danger of being truncated, of no longer growing, of no longer being able to give itself to humanity. History has already shown us similar falls. Some major, others minor. But falls of civilizational models for analogous reasons. In other ways, certainly, but analogous. But even more, it is a threat more than only to Europe, because it intends a global domination that destroys also other cultures, nations and peoples in their true being, to make them stateless without soul, nor roots. Slaves, just like the Europeans, of the power of money that pursues a dehumanized global social model.

Crossing through the middle of the construction of the Puerta del Sol in Madrid, but it would fit the image for any European city, with workers of many different nationalities but hardly Spaniards working, and with the news that there is a lack of waiters and restaurant cooks by the thousands throughout Spain, but also with the caregivers of the elderly that any morning are seen pushing wheelchairs of the elderly in the sun in our streets, it is evident that migrants come to do the work that the nationals do not want to do.

And why don’t they want to do it? One line of answers has to do with working conditions: low pay, much effort. Employers—and individuals—are unable to offer better conditions: some because they cannot, others because it is not convenient for them. This expels nationals and makes immigrants also victims, precariousness fodder, almost slavery; and hand in hand with it, fodder of delinquency and generators of insecurity.

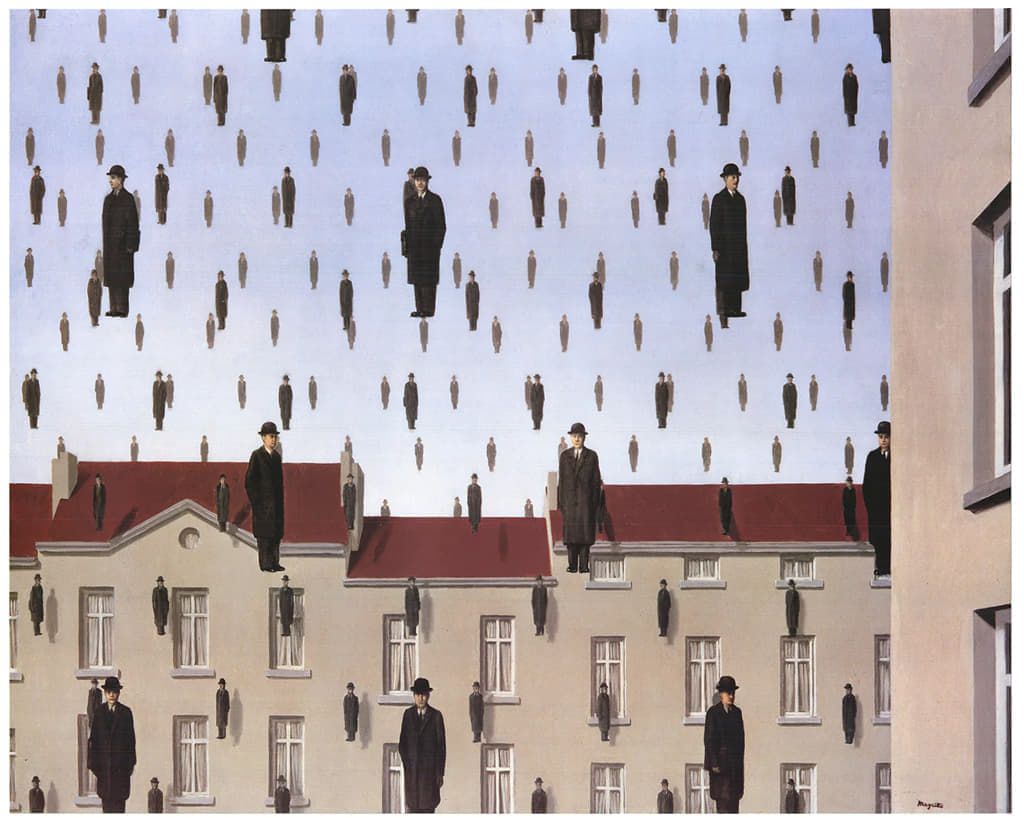

Another line of analysis is linked to a very Western zeitgeist that has to do with comfort, consumerism, hedonism, inflated horizons and university goals, lofty aspirations and the loss of the value of effort, sacrifice, the value of work, humility, realism, or the elimination of everything that is not enjoyable in the fast time of the here and now, even at the cost of giving the power of your life to the machines of AI. There is here a mixture between seeing life as leisure and intuiting a certain renunciation of hope in progress, which says that no matter how much you do, you will not be able to improve. Between the crude conformism and the illusory aspiration based on a simplistic egalitarianism that clashes with the reality of the world, vital inaction, the enemy of realism, is achieved. The digital and virtual world of immediacy, satisfaction and quick self-happiness, of meta-vertical fantasies of perfect lives of luxury and leisure, of Instagramers of brands and lies, of needs created as ways to fill much deeper deficiencies, also contributes to this.

And politics is incapable of dealing with it, entangled in its own social engineering, in its own ideological biases, in its servitude to international agendas, in its particular plans to hold power and benefits, in its privileges of separate strata, in its petty quarrels, in its lack of greatness and aspiration, in its clientelism of interest. And so much so, that one cannot help but think that maybe the supporters of the conspiracy are right. It seems that what is happening is happening on purpose. That they deliberately lead us here to that “you will have nothing, you will owe everything to the state and the corporations, you will not be who you were, and you will only serve the money power as a producer-consumer, without roots or identity or aspirations… and we will make you believe that this way you are happy.” A paranoid and dehumanizing mix between communism and liberalism that leads to terrible dystopias.

But there is hope. There is always hope. Not only because of the resistance to the imposition of this demonic model of man and society that is happening here and now in so many places in our world and in so many different ways. From concrete political movements to cultural battles, to alternative lives that generate different communities, or those dedicated to beauty, true knowledge and the spirit. But also because—and this is what the resistance has to support in its strategies, actions and planning—the human being is not a machine that can be programmed just like that, not until biotechnological transhumanism is imposed.

There are innate cues that will sooner or later—and that later is the dangerous one—make it explode. There are primary human instincts—physical and spiritual—radically incompatible with that dictatorial anti-human dystopia. And that will ensure that evil will never triumph definitively. What is frightening is that until these primordial human forces are set in motion, perhaps the human being suffering too much, allows himself to be dominated too much, is manipulated excessively, is dehumanized as a way for the power of money to achieve its omnipotent domination. The process of technological and economic development in the West has accelerated these dynamics, something that other peoples have not yet experienced because of their level of development—yet. But memory, the achievements of history, tell us that these forces are also real in Europeans. It is a question of setting them in motion, awakening them, activating them.

And that happens by resisting this zeitgeist that dominates us, and by continuing to row in the opposite direction in our own personal and communal selves. They can win, but it will not always be like that. Man will awaken again.

How to rearm him?

Where can we find the personal and social energy to take up again the paths of life and not continue walking along paths of cultural, vital and human suicide?

There is no need to look for these energies far away from us.

In our own European cultural history, in what configured European culture as such, there is an immense vein of energy that from the modernity born with the French Revolution in origin, to the current rampant aggressive and anti-Christian secularization—granddaughter of each other—has been progressively abandoned, like one who moves away from himself and from what nourishes and feeds him, to the point of being estranged from himself and exhausted. Europe has been leaving behind that vital force of its very own, inexhaustible by its very definition to be capable of giving life, which has been Christianity as a unifier of what has been received and a generator of identity and life, to the point of almost ceasing to be, to the point of almost becoming deformed in its own face by the distancing of Europe’s own Christian roots.

And I say almost, although perhaps it would be more appropriate to say that if not deformed, then caricatured. Some factions are still recognizable, some identifying elements of the European Christian identity, manage to continue to appear and be present; the roots are strong and they are not reached by the ice and frost that seems to dominate the surface; and it is precisely this strength and this true rootedness in the European soil after almost two millennia, after having been shaped by Christianity, that can be returned to them, that are capable, like an old oak apparently dry, that allow the best of one’s own identity to sprout.

Europe’s Christian Roots: A Deep Cultural Heritage

Europe, the cradle of ancient civilizations, has been shaped over the centuries by diverse influences. None, however, has left as deep an imprint as Christianity. Europe’s Christian roots go back to Antiquity, when this religion took root and became the cultural foundation of the region.

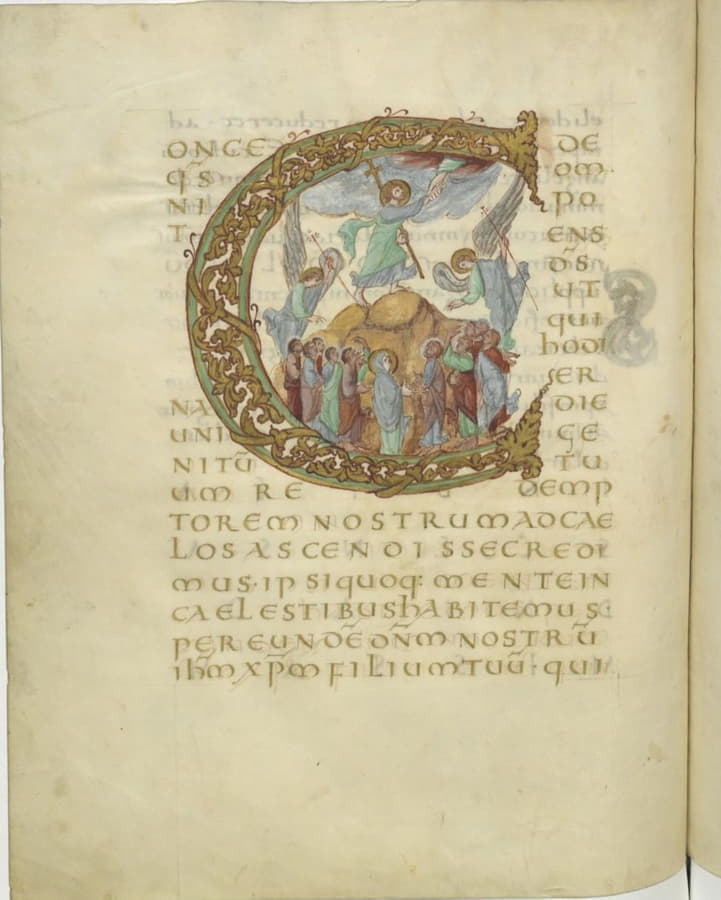

Christianity arrived in Europe in the first centuries of our era, spreading from the Middle East to the West. The central figure of Jesus Christ and His teachings resonated among European populations, and the Christian faith became a unifying element amidst the continent’s cultural diversity.

Over time, Christianity merged with previous Greco-Latin social and political structures as well as those that came to Europe with the barbarian invasions, shaping the Middle Ages and defining the concept of Christendom. The Catholic Church played a crucial role in everyday life, influencing morals, education and politics. Monasteries and cathedrals stood as centers of learning and faith, preserving the cultural and literary heritage of classical antiquity.

The Crusades, which took place between the 11th and 13th centuries, were a testament to the power of the Christian faith in European life. Although driven by diverse motives, the Crusades reflected Europe’s fervent commitment to the defense of Christianity and the expansion of its principles.

The Renaissance, a period of cultural renewal in the 14th-17th centuries, was also steeped in the Christian heritage. Although marked by a revival of interest in classical antiquity, many of the great Renaissance artists and thinkers found inspiration in biblical narratives and Christian theology. The Baroque reached a cultural and artistic dimension never equaled in any other geographic area linked to culture.

The 19th and 20th centuries, children of the liberal revolutions, brought about a series of social and cultural changes of such magnitude that they began to deform the Christian face of Europe until the rampant secularization of modern times; but in spite of this, Christian roots continued to be an essential part of European identity. Christian ethics have influenced the formulation of laws, moral norms and fundamental values that have endured over the centuries and are still a central part of who we Europeans are, and indeed who we can be.

II.

Historical Roots

The adoption of Christianity as the official religion in the Roman Empire marked the beginning of Europe’s Christian identity. From the teachings of the Church Fathers to the consolidation of medieval Christianity, the historical roots laid the foundations for the understanding of the faith on the continent.

Greek Philosophy and the Construction of Christian Identity in Europe

The connection between Greek philosophy and Christian identity in Europe has been a complex journey that has evolved over the centuries. This link began in Antiquity, merging the teachings of philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle with emerging Jewish and Christian traditions. The Church Fathers, such as Augustine of Hippo, integrated philosophical concepts into Christian theology, marking a crucial convergence. The Greek and Latin Fathers built their early theological thought from the understanding that Greek philosophy was the most adequate tool to shape the use of reason in the understanding of theological science. The conviction that the reason of the human being is an immense attribute meant to unite the message of the human dignity of the Gospel of Jesus Christ with the same anthropological gifts in one of the first contributions to the European being: the intrinsic value of the human being created in the image and likeness of God, Who gave him the tools, while perfecting himself with the revelation, to reach a good life. Hence the immense contribution that Stoicism, already in the Roman imperial phase, made to the creation of Christian morality.

During the Middle Ages, the Aristotelian Renaissance influenced scholastic theology, led by figures such as St. Albert the Great and St. Thomas Aquinas, both Dominicans. Aquinas sought to reconcile reason and faith, highlighting the compatibility between Aristotelian philosophy and Christian theology in his monumental work “Summa Theologica”, and the value of philosophy as an instrument of dialogue in his “Summa contra gentiles”.

The Renaissance consolidated the interconnection, with Christian humanists embracing the fusion of classical scholarship and Christian faith, with the paradoxical example of Erasmus of Rotterdam. The emphasis on classical education and ethical values of Greek antiquity marked this phase in a movement that led to the development of an entire Christian philosophy and ethics during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries of which the School of Salamanca, addressing the problems and issues of its historical context, was the humanistic apex.

The Enlightenment introduced challenges, but the influence of Greek philosophy persisted. Greek values, such as freedom, were mixed with the Christian heritage, generating secularized conceptions of morality and politics, incomprehensible without the aforementioned contribution of human dignity of Gospel root.

In conclusion, the relationship between Greek philosophy and Christian identity has been dynamic and enriching. From Antiquity to the Modern Age, this connection forged the intellectual and cultural tradition of Europe, demonstrating the capacity of ideas to shape and seek the true face of the identity of a civilization such as the European one.

Enduring Influence of Roman Law on Europe’s Christian Identity

The connection between Roman Law and Christian identity in Europe has been a journey through the centuries, marked by a profound and lasting influence. From the earliest days of Christianity, when both realities coexisted in the context of the Roman Empire, to the present day, the heritage of the Roman legal system has shaped the institutions, morals and social structure of Christian Europe.

In the first centuries of the Christian era, the Roman legal framework provided the necessary structure for the propagation and organization of Christianity. The notion of Roman citizenship merged with Christian teachings, creating a unique synthesis that influenced equality and social responsibility. Legal and political structures, from the very understanding of the family to the structures of municipalities and dioceses, involved a fruitful interrelationship that shaped the face of Europe.

The Church, during this period, adopted administrative structures of the Roman system, reflecting imperial divisions. The legal and moral authority of the Pope, based on the imperial tradition, took root in the Christian conscience.

The preservation of Roman law in ecclesiastical institutions and the creation of legal codes, such as the Code of Justinian, contributed to the continuity of the Roman legal tradition. These codes served as the basis for civil and canonical legislation, reflecting the synthesis of secular and Christian moral laws.

The recovery of classical knowledge revitalized the influence of Roman law in the Middle Ages. Medieval scholars applied Roman legal teachings in legal education and practice, further consolidating the links between the two disciplines.

The connection between Roman law and Christian identity was reflected in the formulation of fundamental legal concepts. The idea of natural rights and the conception of law as a reflection of divine reason resonated with Christian principles.

As Europe moved into the Modern Age, the influence of Roman law persisted in the legal and political structure of Christian nations. Law as an instrument for the pursuit of the common good and social justice and the protection of individual as well as community rights remained central, rooted in the fusion of Roman tradition and Christian ethics.

In short, the connection between Roman law and Europe’s Christian identity has been a complex and enduring phenomenon. The Roman legal heritage has permeated institutions, morals and the very conception of law in Christian Europe, shaping its collective identity in a way that transcends time and continues to influence the understanding of justice and morality in contemporary European society.

The Influence of the Barbarian Invasions

The barbarian invasions that shook Europe during the last years of the Roman Empire and the early Middle Ages not only left a trail of destruction and political change, but also played a crucial role in the formation of the continent’s common Christian identity. These invasions, carried out by Germanic, Slavic, Norse and other tribes, had a profound impact on the cultural and religious configuration of Europe.

In the decline of the Roman Empire, various barbarian tribes broke through the frontiers, bringing with them their own religious beliefs and practices. As they settled in the conquered lands, they came into contact with the Roman population, which was already marked by the identity of Christianity. This cultural and religious encounter was a complex process that contributed to the creation of a shared Christian identity.

Despite initial tensions between the barbarian communities and the Roman Christians, an integration of these cultures gradually took place. The Church, with its hierarchical structure and its role as a social unifier, played a crucial role in this process. The barbarian leaders, by adopting Christianity, saw in it a tool to consolidate their authority and legitimize their rule in the eyes of the Romanized population.

The barbarian invasions also led to the emergence of new Christian kingdoms in Europe. The Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Vandals, Lombards, Franks, Angles and other groups adopted Christianity, and this act of conversion became a unifying factor in their territories. The figure of the Christian king, invested with a divine mandate, helped to consolidate the identity of these kingdoms and to forge a stronger connection between Christian faith and secular authority.

One of the most significant events was the conversion of the Franks under the reign of Clovis I in the 5th century. In Spain, the figure of Reccared in the kingdom of Toledo was another. This conversion to Christianity, and in particular to Catholicism, not only united the Hispanic Franks and Visigoths under a common religious identity, but also established ties with the Church in Rome. This link with the Papal See strengthened the connection between the Christian regions of Western Europe.

As the Middle Ages progressed, the common Christian identity was further consolidated. The Muslim invasions in the Iberian Peninsula were a reaction that strengthened, in the process of the seven centuries of reconquest, that European Christian identity, shaping a way of being in the cultural and social world totally impregnated with the Christian fact. The Crusades, launched to defend Christianity and recover the Holy Land, were an example of the union of European kingdoms under the banner of Christianity. The Church played an important role in the organization and promotion of these expeditions, contributing to the creation of a European Christian identity that transcended political boundaries.

In conclusion, the barbarian invasions, although initially chaotic and destructive, were a fundamental catalyst in the construction of Europe’s common Christian identity. Through cultural interaction, conversions and the establishment of Christian kingdoms, these invasions contributed to the formation of a shared narrative that endures to this day, shaping the history, culture and identity of Europe.

The Role of the Middle Ages in the Construction of Europe’s Christian Identity

The Middle Ages, also known as the medieval period, played an essential role in the formation and consolidation of Christian identity in Europe. This period, which spanned from approximately the 5th to the 15th century, witnessed a complex interplay between Christian faith, ecclesiastical institutions and socio-economic transformations, contributing significantly to the construction of Europe’s collective identity.

From the collapse of the Roman Empire to the Renaissance, the Catholic Church emerged as a central force in European life during the Middle Ages. Medieval Christianity not only influenced the spiritual sphere, but also shaped politics, culture and education. The Church provided an organizational structure in a world undergoing dramatic changes, thus consolidating the Christian faith as an integral component of European identity. The bishops as social heads and the pope as head of Christendom came to fill the vacuum produced by the power crisis generated by the fall of the Roman Empire, giving in turn accompaniment and light to a new world where cross and sword were in full union.

One of the most prominent aspects of the Middle Ages was the feudal system, which structured society around relationships of vassalage and mutual obligations. The Church played a crucial role in legitimizing this social structure, linking feudal hierarchies with Christian principles of care, hierarchy and the pursuit of the common good. Religious authority supported the idea that monarchs and feudal lords ruled with a divine mandate to care for their subjects, contributing to social cohesion under the banner of Christianity. And this in spite of all the deficiencies that can be argued, because the same human condition, fruit of its anthropological twisted shaft—Kant dixit—that in believers bears the name of original sin, obviously carries. But in spite of such deficiencies, the social orientation models, fruit of Christianity, are the ones that build identity. We are not only who we are, but who we would like to be, as an engine that orients us and pushes us towards a personal and cultural development that marks our identity.

Gothic architecture, with its majestic cathedrals and abbeys, also stands as a tangible testimony to the influence of the Christian faith on medieval European identity and as an image of that desire to ascend, metaphysically, spiritually and ideally, man and society. These monuments were not only places of worship, but also symbols of the greatness of God and the central role of the Church in the life of the community, as well as signs of where society wanted to go—always upwards. Gothic architecture not only elevated the buildings, but also the spirituality of medieval Christianity.

The rise of monastic orders, such as the Benedictines and Cistercians, highlighted the importance of monastic life in the construction of European Christian identity. These monasteries became centers of learning, preservation of classical knowledge and religious practice. Monks and nuns played an essential role in education and in the transmission of the faith, thus contributing to the spiritual cohesion of Europe. Monks guarded the idea of Europe and shaped it with their lives.

The Crusades, military expeditions undertaken in the name of Christianity to reclaim the Holy Land, also left an indelible mark on European identity. Although motivated by a variety of factors, the Crusades reflected Europe’s fervent commitment to the defense of Christianity and the expansion of its principles in a context of interaction with the Islamic and Eastern world.

As the Middle Ages progressed, intellectual movements emerged that fused classical philosophy with Christian theology. Scholasticism, represented by figures such as St. Thomas Aquinas, sought to harmonize reason and faith, thus contributing to a deeper and more articulate understanding of Christian identity. The theological and philosophical debates of this period left a lasting mark on the European worldview.

In conclusion, the Middle Ages played a crucial role in the construction of Europe’s Christian identity. Through the Church, monastic institutions, monumental architecture and intellectual movements, this period left a lasting legacy that influenced the way Europeans understood their faith and their place in the world. The Middle Ages were not a time of darkness, but a time of ferment and development that helped forge the Christian identity that remains an integral part of Europe’s heritage.

The Renaissance and its Contribution to the Construction of European Christian Identity

The Renaissance, a period of cultural and artistic renewal that flourished in Europe from the fourteenth to the seventeenth century, left a profound mark on the construction of the continent’s Christian identity. Although often associated with a revival of interest in classical Greco-Latin culture, the Renaissance also played a crucial role in the evolution and affirmation of Christian identity.

During this period, humanist currents rediscovered and revalued the works of classical antiquity, including the philosophies of Plato and Aristotle. However, this revival of classical thought did not come at the expense of Christian identity; rather, it merged in a unique way with the Christian tradition, giving rise to a distinctive cultural synthesis.

Renaissance humanists advocated an education that incorporated both Christian principles and the ethical and aesthetic values of antiquity. This holistic approach allowed for a deeper appreciation of the Christian faith by placing it in a broader context of knowledge. Figures such as Erasmus of Rotterdam, Luis Vives or Francisco de Vitoria, promoted the idea that classical scholarship and Christian faith were not incompatible, but, on the contrary, complemented each other.

Renaissance architecture also reflected the interconnection between Christian identity and classical ideals. Churches and cathedrals, while often incorporating classical architectural elements, retained their function as places of Christian worship. The grandeur and elegance of these structures not only highlighted the glory of God, but also symbolized the spiritual rebirth of Christianity.

Renaissance art, characterized by a more realistic and humanized representation of the human figure, also influenced the visual expression of Christian identity. Religious paintings and sculptures captured devotion and spirituality with renewed intensity, providing the faithful with a more intimate connection to their faith.

In addition, the Renaissance brought about a revival of biblical and theological studies. Figures such as Thomas Aquinas, despite belonging to an earlier era, experienced renewed interest and study. The fusion of Aristotelian philosophy with Christian theology, known as scholasticism, found an intellectual renaissance during this period, allowing for a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the faith.

In short, the Renaissance contributed significantly to the construction of European Christian identity by integrating classical values with the Christian tradition. This cultural synthesis not only enriched knowledge and artistic expression, but also provided a solid basis for understanding the faith in a broader context. The Renaissance did not mark a separation between the classical and the Christian, but instead fostered a harmonious coexistence that influenced European identity for centuries.

The Construction of European Christian Identity in the Baroque: An Artistic and Spiritual Splendor

The Baroque period, which spanned roughly from the seventeenth century to the mid-eighteenth century, was a time of cultural and spiritual transformation in Europe. This period not only witnessed political and social changes, but also played a fundamental role in the construction and consolidation of Christian identity on the continent.

The Baroque emerged at a time of tensions and conflicts, such as the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation. These movements had a profound impact on European religiosity and contributed to the shaping of Christian identity during this period. The Catholic Church, in particular, sought to revitalize its spiritual influence in response to the challenges posed by the Reformation. The threat of Islam through the Turkish danger was of course also the driving force, in Carl Schmitt’s inspiration, of an enemy against which to reaffirm and strengthen the common identity, as Lepanto or Vienna showed.

Baroque architecture, with its opulence and theatricality, became a crucial means of expressing Christian identity. Baroque churches, with their ornate detailing, use of the play of light and shadow, and the monumentality of their designs, sought to inspire a sense of awe and devotion. St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, is an outstanding example of this Baroque architecture that sought to elevate the soul to the divine, but all of Europe, from Lisbon to Prague, from Seville to Vienna, shows it.

Baroque painting and sculpture also played an essential role in the construction of Christian identity. Masterpieces by artists such as Caravaggio, Zurbarán, Rubens and Velázquez depicted biblical scenes and portraits of saints with an emotional intensity and realism that sought to directly involve viewers in the religious narrative. Baroque sculpture, with its dramatic and dynamic imagery, provided a palpable representation of Christian spirituality.

Baroque music, especially sacred music, played a central role in expressing Christian identity. Composers such as Bach, Handel and Monteverdi created masterpieces that celebrated the faith and were performed in liturgical settings. Opera, although often secular in theme, also incorporated religious and moral elements, contributing to the cultural richness of Christian identity.

Baroque literature addressed religious themes with philosophical and spiritual depth. The works of mystics such as St. Teresa of Avila and St. John of the Cross explored the intimate relationship with the divine; the dramas of a Calderón de la Barca or a Lope de Vega brought that identity to the common people, while theological treatises provided—Friar Luis de Granada, a true bestseller of his time—an intellectual basis for understanding the faith. Baroque poetry, often rich in symbolism and biblical allusions, also contributed to the construction of Christian identity.

The Baroque was deeply marked in a Catholic key by the Counter-Reformation, an effort by the Catholic Church to revitalize and reaffirm its doctrine in response to the criticisms of the Protestant Reformation. Baroque popes, such as Innocent X and Alexander VII, played an important role in promoting the Catholic faith and building a unified Christian identity.

The Nineteenth Century and the Transformation of Christian Identity in Europe: Challenges, Renewal and Spiritual Evolution

The 19th century was a time of profound changes in Europe, both socially and culturally, changes that were the children of the civilizational debacle that was the French Revolution. These changes had a significant impact on the Christian identity of the continent, generating challenges, but also giving rise to new forms of spiritual expression and renewal.

The 19th century witnessed a series of social changes that challenged the historical position of the Church in European society. The rise of nationalist movements, accelerated industrialization, and the ideals of the Enlightenment influenced the perception of religious authority. Secularization gained ground, leading to a decline in the direct influence of the Church in the public sphere.

Despite the challenges, the 19th century was also a time of reform movements within the Church. In the Catholic Church, the Catholic Restoration movement sought to revitalize and strengthen the Church’s position in the face of social change. This impulse of spiritual renewal spread through various religious orders and lay movements, marking an effort to adapt to the demands of the time, especially in the field of education, with the birth of a multitude of religious congregations, mostly female, which came to address the new situations that the nascent liberal states were unable to meet.

Spiritual renewal in the 19th century was expressed in movements such as the Oxford Movement in the Anglican Church and the revival of Catholicism in several European countries. These movements sought to revive religious devotion, deepen theological understanding and restore liturgical elements considered essential to Christian identity, as well as theology and scholarship.

In parallel, religious awakening movements developed, such as the Second Great Awakening in America and its echoes in Europe. These movements emphasized the personal experience of faith, conversion and active participation in the religious community. New denominations and Christian communities emerged that advocated a spirituality more centered on individual experience.

The 19th century was also a time of missionary expansion, with a renewed emphasis on evangelization at the time of African and Asian colonialism in non-Christian regions of the world. This cultural and religious encounter raised questions about the diversity of beliefs and traditions, contributing to a deeper reflection on Christian identity in a global context.

The 19th century also witnessed the emergence of theological and philosophical developments that influenced the understanding of faith. Philosophers such as Søren Kierkegaard explored the relationship between faith and reason, while theologians such as Friedrich Schleiermacher argued for a more focused interpretation of religious experience. Even from critical paths with a bourgeois model that was being imposed and that also affected the common believers, such as Leon Bloy, with his verbal scourge and religious depth, or Dostoevsky with his existential novels of deep spirituality.

Slavery, industrialization and social inequalities posed ethical challenges that Christian identity had to confront. Social justice movements inspired by Christian principles emerged to address these issues, making connections between faith and social action. And at the same time to confront the materialist movements of the three revolutions, Marx, Nietzsche and Freud, which were giving birth to a new world increasingly removed from the faith and Christian principles that had shaped Europe for more than a millennium and a half.

In short, the nineteenth century was a period of complexity and change for Christian identity in Europe. Although it faced significant challenges because of secularization and social change, it was also a time of spiritual renewal, reform and theological reflection that laid the foundation for the diversity and evolution of Christian identity in the twentieth century and beyond.

The Twentieth Century to the Second World War: Challenges and Resilience in Europe’s Christian Identity

The 20th century witnessed a series of events that profoundly impacted Europe’s Christian identity. From geopolitical tensions to social and cultural changes, this period posed significant challenges, but also evidenced the resilience and persistence of the Christian faith in the midst of adversity.

It began with global conflicts and political tensions that had a direct impact on Europe’s Christian identity. The First World War truly marked the beginning of the century and left European society marked by devastation and loss, yet open to such technological change, as Ernst Jünger saw so well, that it would mark the following century.

The totalitarian regimes that emerged in the 1930s presented additional challenges to religious practice, as several European countries under absolute state regimes, such as Soviet communism or Nazism in Germany, sought to control and manipulate religious expression. Religious persecution affected Christian communities, evidencing the struggle of faith in the face of totalitarian ideologies that sought to suppress any allegiance other than to the state.

Despite the political challenges, the 20th century also witnessed significant efforts in favor of interreligious dialogue and ecumenism. Movements such as the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) in the Catholic Church and the Edinburgh Conference (1910) in Protestantism sought to promote unity and understanding among the various branches of Christianity, as well as with other religions.

The 20th century witnessed important theological developments that influenced Christian identity. Figures such as Chenu, Congar, Schillebeeckx, Karl Barth or Dietrich Bonhoeffer responded to the challenges of the time, reflecting on the relationship between Christian faith and social responsibility in a context marked by war and injustice.

During World War II, the Church played a key role in the resistance against totalitarian regimes. In some cases, such as the resistance of the Catholic Church in Poland, it became a beacon of hope and resistance against oppression. After the war, the Church also participated in reconstruction efforts, seeking to restore not only physical structures, but also communities and faith, and as a reminder, especially under the countries of communist terror, of authentic European Christian identity.

The second half of the 20th century was marked by the crisis of modernity, where the Christian faith faced challenges related to secularization, loss of institutional authority and growing cultural diversity. However, spiritual renewal movements also emerged that sought to revitalize religious practice in a changing context.

Despite the difficulties, the 20th century saw the development of numerous charitable and social organizations based on Christian principles. From local charities to international organizations, the Church and individual Christians played an active role in addressing social and humanitarian problems, demonstrating a continuing commitment to the Christian principles of love and justice, which best represent the face of European identity.

In summary, the 20th century up to World War II was a complex and challenging period for Europe’s Christian identity. Despite conflicts and tensions, the resilience of the Christian faith was manifested in interreligious dialogue, ecumenical efforts, the Church’s active role in resistance and reconstruction, and the continuing ethical and social influence of Christianity in European society.

The Second Half of the Twentieth Century: Transformations and Continuities in Europe’s Christian Identity

The second half of the 20th century was a period of radical changes that continued to influence Christian identity in Europe. From the impact of the Cold War to the emergence of social and cultural movements, the Christian faith faced new challenges and adapted to a constantly changing world.

The Cold War divided Europe into opposing ideological blocs, and religion was often caught in the middle of this conflict. In Eastern Europe, communism imposed significant restrictions on religious practice, especially in countries such as the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe controlled by the communist bloc.

The second half of the 20th century witnessed counterculture movements and significant social changes that affected the perception of religion in society. The Cultural Revolution of the 1960s, the rise of individualism and the emergence of new ethical paradigms posed challenges to traditional structures, including Christian identity.

In the Catholic Church, the Second Vatican Council, held between 1962 and 1965, marked a crucial moment of renewal. The council sought to adapt the Church to contemporary challenges by promoting openness to interreligious and ecumenical dialogue. These efforts influenced the understanding of Christian identity in a context of growing religious pluralism.

The second half of the 20th century also witnessed the emergence of charismatic movements within Christianity, especially in the Catholic Church and Protestant denominations. These movements, characterized by intense spiritual experiences and an emphasis on the gifts of the Holy Spirit, sought to revitalize the faith and attract a new generation of believers.

A special emphasis on Social Justice and Human Rights characterized this period, which saw a rise in the Catholic Church especially, but also the Reformed Churches, in social justice and human rights. Religious leaders from John XXIII to John Paul II advocated for the defense of human rights and solidarity with the oppressed, contributing to the construction of a Christian identity committed to justice and human dignity.

Technological advances, changes in family structure and ethical debates on issues such as abortion, contraception and sexuality posed significant ethical challenges to Christian identity in the second half of the 20th century. The Church was forced to address these issues from an ethical and theological perspective, influencing the understanding of faith in the modern context. Although perhaps not always knowing how to respond fully.

Despite efforts at renewal, the second half of the 20th century also witnessed a decline in religious practice in some regions of Europe. Secularism and the influence of secular culture contributed to a decline in affiliation with religious institutions and a change in the dynamics of Christian identity. Consumer, technological, secular, secularist, materialistic models—both liberal and communist—have been gaining the upper hand in the neglect of Europe’s true Christian identity.

In short, the second half of the 20th century was a complex and dynamic period for Europe’s Christian identity. The Church faced significant challenges, but also responded to them through efforts of renewal, dialogue and adaptation to changing social and cultural dynamics. Christian identity, although affected by the transformations of the times, proved to be resilient and able to try to adapt to the challenges of a changing world.

Christian Identity in the Construction of the European Union: Between Religious Diversity and Shared Values

The European Union (EU) has been a project that has sought unity and cooperation among nations with rich cultural, historical and religious diversity. In this context, Christian identity has played a complex role as the EU has evolved in an environment characterized by religious plurality and commitment to shared values.

European history is deeply rooted in the Christian tradition. The influence of Christianity has been evident in the formation of institutions, laws and values that have shaped European civilization. From the Holy Roman Empire to the contribution of Christian thinkers to philosophy and ethics, Christian identity has left an indelible mark on the building of Europe.

The fathers of the European Union, Jean Monnet, Robert Schuman, Konrad Adenauer, Alcide De Gasperi and Paul-Henri Spaak, were clear about this, even beyond their own personal convictions. Europe would not be Europe without the recognition and care of its Christian identity.

Christian ethics have contributed to the formulation of fundamental principles underpinning the EU. Human dignity, social justice and solidarity; Christian values rooted in biblical teaching, have been adopted as guiding principles in building a united and peaceful Europe.

Certainly, as the EU has grown and expanded, religious diversity has become more evident. Interfaith dialogue has become an essential component in promoting mutual understanding between different faith communities. Despite its Christian roots, the EU recognizes and respects religious plurality as an integral part of its contemporary identity. But one certainly cannot engage in dialogue by renouncing who one is.

Throughout the negotiations for the formation of the EU, there has been an attempt, perhaps excessively so, to balance Christian roots with a secular approach to decision-making. The European institutions have adopted a secular approach, ensuring separation between religion and government to guarantee equality and religious freedom for all citizens, in a move beyond pendulum swinging, almost renouncing them.

Christian movements, such as the Taizé Community, have played an active role in promoting European unity and building bridges between communities. Their commitment to Christian values of reconciliation and fraternity has resonated with the vision of a united and peaceful Europe. But, and here is one of the main lessons that we should not lose, without renouncing our own identity.

In the 21st century, the EU is facing challenges related to religious diversity, the rise of secularism and the growing pressure of political movements that seek to highlight national identities or marginal and minority identities. Reflection on Christian identity in this context involves finding a balance that celebrates the Christian heritage while committing to an inclusive and respectful approach towards all faiths and non-beliefs, but without giving up what has made Europe who it is.

In conclusion, Christian identity has left a profound mark on the construction of the European Union, influencing its fundamental ethical values and contributing to the vision of a united Europe. However, the EU has also evolved to embrace religious diversity and ensure that its principles reflect respect and equality for all citizens, regardless of their beliefs. Christian history and identity remain significant elements in the evolving cultural and ethical fabric of the European Union.

Vicente Niño Orti, OP is a Dominican friar. He studied the Law and Theology and is the Area Director of the Saint Dominic Educational Foundation.

Featured: St. Helena and the True Cross, by Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano; painted ca. 1495.