Given the current attack on the life of the mind of a child by a trans activist educational system and its abettors (teachers), seeking to to destroy the innocense of children that they may readily be transformed into mutilated eunuchs—we thought it would be best to return to the ideas of Friedrich Froebel (1782-1852), the man who created education for the very young, which he labeled Kindergarten (a garden for children).

What follows is in two parts: first a brief life of Froebel by Nora Archibald Smith (1859–1934), the American writer and education, and then the words of wisdom from the man himself, taken from his letters and published works.

Part I: The Life of Friedrich Froebel

It was Froebel who said, “The clearer the thread that runs through our lives backward to our childhood, the clearer will be our onward glance to the goal;” and in the fragment of autobiography he has left us, he illustrates forcibly the truth of his own saying. The motherless baby who plays alone in the village pastor’s quiet house, the dreamy child who wanders solitary in the high-walled garden; the thoughtful lad, neglected, misunderstood, who forgets the harsh realities of life in pondering the mysteries of the flowers, the contradictions of existence, and the dogmas of orthodox theology; who decides in early boyhood that the pleasures of the senses are without enduring influence and therefore on no account to be eagerly pursued;—these presentments of himself, which he summons up for us from the past, show the vividness of his early recollections and indicate the course which the stream of his life is to run.

The coldness and injustice of the new mother who assumed control of the household when he was four years old, his isolation from other children, the merely casual notice he received from the busy father absorbed in his parish work, all tended to turn inward the tide of his mental and spiritual life. He studied himself, not only because it was the bent of his nature, but because he lacked outside objects of interest; and to this early habit of introspection we owe many of the valuable features of his educational philosophy. Whoever has learned thoroughly to understand one child, has conquered a spot of firm ground on which to rest while he studies the world of children; and because the great teacher realized this truth, because he longed to give to others the means of development denied to himself, he turns for us the heart-leaves of his boyhood.

It would appear that Froebel’s characteristics were strongly marked and unusual from the beginning. Called by every one “a moon-struck child” in Oberweissbach, the village of his birth, he was just as unanimously considered “an old fool” when, crowned with the experience of seventy years, he played with the village children on the green hills of Thuringia. The intensity of his inward life, the white heat of his convictions, his absolute blindness to any selfish idea or aim, his enthusiasm, the exaltation of his spiritual nature, all furnish so many cogent reasons why the people of any day or of any community should have failed to understand him, and scorned what they could not comprehend. It is the old story of the seers and the prophets repeated as many times as they appear; for “these colossal souls,” as Emerson said, “require a long focal distance to be seen.”

At ten years old the sensitive boy was fortunately removed from the uncongenial atmosphere of the parental household; and in his uncle’s home he spent five free and happy years, being apprenticed at the end of this time to a forester in his native Thuringian woods. Then followed a year’s course in the University of Jena, and four years spent in the study of farming, in clerical work of various kinds, and in land-surveying. All these employments, however, Froebel himself felt to be merely provisional; for like the hazel wand in the diviner’s hand, his instinct was blindly seeking through these restless years the well-spring of his life.

In Frankfort, where he had gone intending to study architecture, Destiny touched him on the shoulder, and he turned and knew her. Through a curious combination of circumstances he gained employment in Herr Gruner’s Model School, and it was found at once that he was what the Germans love to call “a teacher by the grace of God.” The first time he met his class of boys he tells us that he felt inexpressibly happy; the hazel wand had found the waters and was fixed at last. From this time on, all the events of his life were connected with his experience as a teacher. Impelled as soon as he had begun his work by a desire for more effective methods, he visited Yverdon, then the centre of educational thought, and studied with Pestalozzi. He went again in 1808, accompanied by three pupils, and spent two years there, alternately studying and teaching.

There was a year of lectures at Göttingen after this, and one at the University of Berlin, accompanied by unceasing study and research both in literary and scientific lines; but in the fateful year 1813 this quiet student life was broken in upon, for impelled by strong moral conviction, Froebel joined Baron von Lützow’s famous volunteer corps, formed to harass the French by constant skirmishes and to encourage the smaller German States to rise against Napoleon.

No thirst for glory prompted this action, but a lofty conception of the office of the educator. How could any young man capable of bearing arms, Froebel says, become a teacher of children whose Fatherland he had refused to defend? how could he in after years incite his pupils to do something noble, something calling for sacrifice and unselfishness, without exposing himself to their derision and contempt? The reasoning was perfect, and he made practice follow upon the heels of theory as closely as he had always done since he became master of his fate.

After the Peace of Paris he settled down for a time to a quiet life in the mineralogical museum at the University of Berlin, his duties being the care, arrangement, and investigation of crystals. Surrounded thus by the exquisite formations whose development according to law is so perfect, whose obedience to the promptings of an inward ideal so complete, he could not but learn from their unconscious ethics to look into the depths of his own nature, and there recognize more clearly the purpose it was intended to work out.

In 1816 he quietly gave up his position, and taking as pupils five of his nephews, three of whom were fatherless, he entered upon his life work, the first step in which was the carrying out of his plan for a “Universal German Educational Institute.” He was without money, of course, as he had always been and always would be—his hands were made for giving, not for getting; he slept in a barn on a wisp of straw while arranging for his first school at Griesheim; but outward things were so little real to him in comparison with the life of the spirit, that bodily privations seemed scarcely worth considering. The school at Keilhau, to which he soon removed, the institutions later established in Wartensee and Willisau, the orphanage in Burgdorf, all were most successful educationally, but, it is hardly necessary to say, were never a source of profit to their head and founder.

Through the twenty succeeding years, busy as he was in teaching, in lecturing, in writing, he was constantly shadowed by dissatisfaction with the foundation upon which he was building. A nebulous idea for the betterment of things was floating before him; but it was not until 1836 that it appeared to his eyes as a “definite truth.” This definite truth, the discovery of his old age, was of course the kindergarten; and from this time until the end, all other work was laid aside, and his entire strength given to the consummate flower of his educational thought.

The first kindergarten was opened in 1837 at Blankenburg (where a memorial school is now conducted), and in 1850 the institution at Marienthal for the training of kindergartners was founded, Froebel remaining at its head until his death two years after.

With the exception of that remarkable book, The Education of Man (1826), his most important literary work was done after 1836; Pedagogics of the Kindergarten, the first great European contribution to the subject of child-study, appearing from 1837 to 1840 in the form of separate essays, and the Mutter-und-Kose Lieder (Mother-Play) in 1843. Many of his educational aphorisms and occasional speeches were preserved by his great disciple the Baroness von Marenholtz-Bülow in her Reminiscences of Froebel; and though two most interesting volumes of his correspondence have been published, there remain a number of letters, as well as essays and educational sketches, not yet rendered into English.

Froebel’s literary style is often stiff and involved, its phrases somewhat labored, and its substance exceedingly difficult to translate with spirit and fidelity; yet after all, his mannerisms are of a kind to which one easily becomes accustomed, and the kernel of his thought when reached is found well worth the trouble of removing a layer of husk. He had always an infinitude of things to say, and they were all things of purpose and of meaning; but in writing, as well as in formal speaking, the language to clothe the thought came to him slowly and with difficulty. Yet it appears that in friendly private intercourse he spoke fluently, and one of his students reports that in his classes he was often “overpowering and sublime, the stream of his words pouring forth like fiery rain.”

It is probable that in daily life Froebel was not always an agreeable house-mate; for he was a genius, a reformer, and an unworldly enthusiast, believing in himself and in his mission with all the ardor of a heart centred in one fixed purpose. He was quite intolerant of those who doubted or disbelieved in his theories, as well as of those who, believing, did not carry their faith into works. The people who stood nearest him and devoted themselves to the furthering of his ideas slept on no bed of roses, certainly; but although he sometimes sacrificed their private interests to his cause, it must not be forgotten that he first laid himself and all that he had upon the same altar. His nature was one that naturally inspired reverence and loyalty, and drew from his associates the most extraordinary devotion and self-sacrifice. Then, as now, women were peculiarly attracted by his burning enthusiasm, his prophetic utterances, and his lofty views of their sex and its mission; and then, as now, the almost fanatical zeal of his followers is perhaps to be explained by the fact that he gives a new world-view to his students,—one that produces much the same effect upon the character as the spiritual exaltation called “experiencing religion.”

He was twice married, in each case to a superior woman of great gifts of mind and character, and both helpmates joyfully took up a life of privation and care that they might be associated with him and with his work. Those memorable words spoken of our Washington—”Heaven left him childless that a nation might call him father,” are even more applicable to Froebel, for his wise and tender fatherhood extends to all the children of the world. When he passed through the village streets of his own country, little ones came running from every doorstep; the babies clinging to his knees and the older ones hanging about his neck and refusing to leave the dear play-master, as they called him. So the kindergartners love to think of him to-day—the tall spare figure, the long hair, the wise, plain, strong-featured face, the shining eyes, and the little ones clustering about him as they clustered about another Teacher in Galilee, centuries ago.

Froebel’s educational creed cannot here be cited at length, but some of its fundamental articles are:

- The education of the child should begin with its birth, and should be threefold, addressing the mental, spiritual, and physical natures.

- It should be continued as it has begun, by appealing to the heart and the emotions as the starting-point of the human soul.

- There should be sequence, orderly progression, and one continuous purpose throughout the entire scheme of education, from kindergarten to university.

- Education should be conducted according to nature, and should be a free, spontaneous growth—a development from within, never a prescription from without.

- The training of the child should be conducted by means of the activities, needs, desires, and delights, which are the common heritage of childhood.

- The child should be led from the beginning to feel that one life thrills through every manifestation of the universe, and that he is a part of all that is.

- The object of education is the development of the human being in the totality of his powers as a child of nature, a child of man, and a child of God.

These principles of Froebel’s, many of them the products of his own mind, others the pure gold of educational currency upon which he has but stamped his own image, are so true and so far-reaching that they have already begun to modify all education and are destined to work greater magic in the future. The great teacher’s place in history may be determined, by-and-by, more by the wonderful uplift and impetus he gave to the whole educational world, than by the particular system of child-culture in connection with which he is best known to-day.

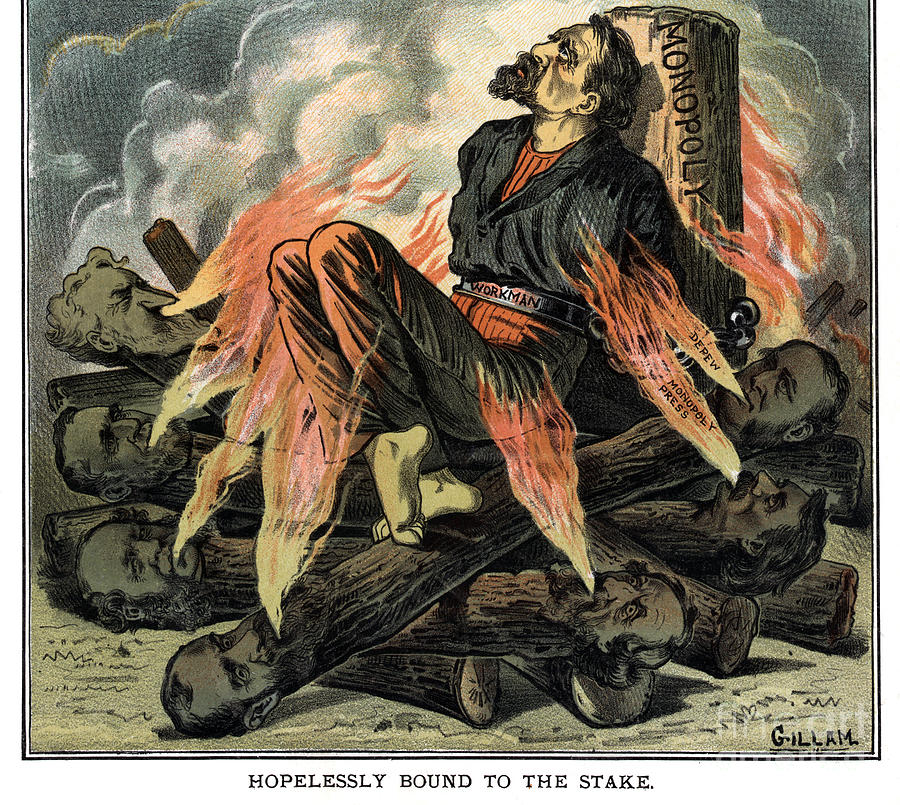

Judged by ordinary worldly standards, his life was an unsuccessful one, full of trials and privations, and empty of reward. His death-blow was doubtless struck by the prohibition of kindergartens in Prussia in 1851, an edict which remained nine years in force. His strength had been too sorely tried to resist this final crushing misfortune, and he passed away the following year. His body was borne to the grave through a heavy storm of wind and rain that seemed to symbolize the vicissitudes of his earthly days, while as a forecast of the future the sun shone out at the last moment, and the train of mourners looked back to see the low mound irradiated with glory.

In Thuringia, where the great child-lover was born, the kindergartens, his best memorials, cluster thickly now; and on the face of the cliffs that overhang the bridle-path across the Glockner mountain may be seen in great letters the single word Froebel, hewn deep into the solid rock.

(Nora Archibald Smith)

Part II: Excerpts from Froebel’s Work

The Right of the Child

All that does not grow out of one’s inner being, all that is not one’s own original feeling and thought, or that at least does not awaken that, oppresses and defaces the individuality of man instead of calling it forth, and nature becomes thereby a caricature. Shall we never cease to stamp human nature, even in childhood, like coins? to overlay it with foreign images and foreign superscriptions, instead of letting it develop itself and grow into form according to the law of life planted in it by God the Father, so that it may be able to bear the stamp of the Divine, and become an image of God?…

This theory of love is to serve as the highest goal and polestar of human education, and must be attended to in the germ of humanity, the child, and truly in his very first impulses. The conquest of self-seeking egoism is the most important task of education; for selfishness isolates the individual from all communion, and kills the life-giving principle of love. Therefore the first object of education is to teach to love, to break up the egoism of the individual, and to lead him from the first stage of communion in the family through all the following stages of social life to the love of humanity, or to the highest self-conquest by which man rises to Divine unity….

Women are to recognize that childhood and womanliness (the care of childhood and the life of women) are inseparably connected; that they form a unit; and that God and nature have placed the protection of the human plant in their hands. Hitherto the female sex could take only a more or less passive part in human history, because great battles and the political organization of nations were not suited to their powers. But at the present stage of culture, nothing is more pressingly required than the cultivation of every human power for the arts of peace and the work of higher civilization. The culture of individuals, and therefore of the whole nation, depends in great part upon the earliest care of childhood. On that account women, as one half of mankind, have to undertake the most important part of the problems of the time, problems that men are not able to solve. If but one half of the work be accomplished, then our epoch, like all others, will fail to reach the appointed goal. As educators of mankind, the women of the present time have the highest duty to perform, while hitherto they have been scarcely more than the beloved mothers of human beings….

But I will protect childhood, that it may not as in earlier generations be pinioned, as in a strait-jacket, in garments of custom and ancient prescription that have become too narrow for the new time. I shall show the way and shape the means, that every human soul may grow of itself, out of its own individuality. But where shall I find allies and helpers if not in women, who as mothers and teachers may put my idea in execution? Only intellectually active women can and will do it. But if these are to be loaded with the ballast of dead knowledge that can take no root in the unprepared ground, if the fountains of their own original life are to be choked up with it, they will not follow my direction nor understand the call of the time for the new task of their sex, but will seek satisfaction in empty superficiality.

To learn to comprehend nature in the child—is not that to comprehend one’s own nature and the nature of mankind? And in this comprehension is there not involved a certain degree of comprehension of all things else? Women cannot learn and take into themselves anything higher and more comprehensive. It should therefore at least be the beginning, and the love of childhood should be awakened in the mind (and in a wider sense, this is the love of humanity), so that a new, free generation of men can grow up by right care.

(From Reminiscences of Friedrich Froebel, by Baroness B. von Marenholtz-Bülow), (1877).

Evolution

What shall we learn from our yearning look into the heart of the flower and the eye of the child? This truth: Whatever develops, be it into flower or tree or man, is from the beginning implicitly that which it has the power to become. The possibility of perfect manhood is what you read in your child’s eye, just as the perfect flower is prophesied in the bud, or the giant oak in the tiny acorn. A presentiment that the ideal or generic human being slumbers, dreams, stirs in your unconscious infant—this it is, O mother, which transfigures you as you gaze upon him. Strive to define to yourself what is that generic ideal which is wrapped up in your child. Surely, as your child—or in other words, as child of man—he is destined to live in the past and future as well as in the present. His earthly being implies a past heaven; his birth makes a present heaven; in his soul he holds a future heaven. This threefold heaven, which you also bear within you, shines out on you through your child’s eyes.

The beast lives only in the present. Of past and future he knows naught. But to man belong not only the present, but also the future and the past. His thought pierces the heaven of the future, and hope is born. He learns that all human life is one life; that all human joys and sorrows are his joys and sorrows, and through participation enters the present heaven—the heaven of love. He turns his mind towards the past, and out of retrospection wrests a vigorous faith. What soul could fail to conquer an invincible trust in the pure, the good, the holy, the ideally human, the truly Divine, if it would look with single eye into its own past, into the past of history? Could there be a man in whose soul such a contemplation of the past would fail to blossom into devout insight, into self-conscious and self-comprehending faith? Must not such a retrospect unveil the truth? Must not the beauty of the unveiled truth allure him to Divine doing, Divine living? All that is high and holy in human life meets in that faith which is born of the unveiling of a heaven that has always been; in that hope born of a vision of the heaven that shall be; in that love which creates a heaven in the eternal Now. These three heavens shine out upon you through your child’s eye. The presentiment that he carries these three heavens within him transfigures your countenance as you gaze upon him. Cherish this premonition, for thereby you will help him to make his life a musical chord wherein are blended the three notes of faith, hope, and love. These celestial virtues will link his life with the Divine life through which all life is one—with the God who is the supernal fountain of life, light, and love….

Higher and more important than the cultivation of man’s outer ear, is the culture of that inner sense of harmony whereby the soul learns to perceive sweet accord in soundless things, and to discern within itself harmonies and discords. The importance of wakening the inner ear to this music of the soul can scarcely be exaggerated. Learning to hear it within, the child will strive to give it outer form and expression; and even if in such effort he is only partially successful, he will gain thereby the power to appreciate the more successful effort of others. Thus enriching his own life by the life of others, he solves the problem of development. How else were it possible within the quickly fleeting hours of mortal life to develop our being in all directions, to fathom its depths, scale its heights, measure its boundaries? What we are, what we would be, we must learn to recognize in the mirror of all other lives. By the effort of each, and the recognition of all, the Divine man is revealed in humanity….

Against the bright light which shines on the smooth white wall is thrust a dark object, and straightway appears the form which so delights the child. This is the outward fact; what is the truth which through this fact is dimly hinted to the prophetic mind? Is it not the creative and transforming power of light, that power which brings form and color out of chaos, and makes the beauty which gladdens our hearts? Is it not more than this—a foreshadowing, perhaps, of the spiritual fact that our darkest experiences may project themselves in forms that will delight and bless, if in our hearts shines the light of God? The sternest crags, the most forbidding chasms, are beautiful in the mellow sunshine; while the fairest landscape loses all charm, and indeed ceases to be, when the light which created it is withdrawn. Is it not thus also with our lives? Yesterday, touched by the light of enthusiastic emotion, all our relationships seemed beautiful and blessed; to-day, when the glow of enthusiasm has faded, they oppress and repulse us. Only the conviction that it is the darkness within us which makes the darkness without, can restore the lost peace of our souls. Be it therefore, O mother, your sacred duty to make your darling early feel the working both of the outer and inner light. Let him see in one the symbol of the other, and tracing light and color to their source in the sun, may he learn to trace the beauty and meaning of his life to their source in God.

(From The Mottoes and Commentaries of Mother-Play), (1895). Translation of Susan E. Blow.

Aphorisms

I see in every child the possibility of a perfect man.

The child-soul is an ever-bubbling fountain in the world of humanity.

The plays of childhood are the heart-leaves of the whole future life.

Childish unconsciousness is rest in God.

From each object of nature and of life, there goes a path toward God.

Perfect human joy is also worship, for it is ordered by God.

The first groundwork of religious life is love—love to God and man—in the bosom of the family.

Childhood is the most important stage of the total development of man and of humanity.

Women must make of their educational calling a priestly office.

Isolation and exclusion destroy life; union and participation create life.

Without religious preparation in childhood, no true religion and no union with God is possible for men.

The tree germ bears within itself the nature of the whole tree; the human being bears in himself the nature of all humanity; and is not therefore humanity born anew in each child?

In the children lies the seed-corn of the future.

The lovingly cared for, and thereby steadily and strongly developed human life, also the cloudless child life, is of itself a Christ-like one.

In all things works one creative life, because the life of all things proceeds from one God.

Let us live with our children: so shall their lives bring peace and joy to us; so shall we begin to be and to become wise.

What boys and girls play in earliest childhood will become by-and-by a beautiful reality of serious life; for they expand into stronger and lovelier youthfulness by seeking on every side appropriate objects to verify the thoughts of their inmost souls.

This earliest age is the most important one for education, because the beginning decides the manner of progress and the end. If national order is to be recognized in later years as a benefit, childhood must first be accustomed to law and order, and therein find the means of freedom. Lawlessness and caprice must rule in no period of life, not even in that of the nursling.

The kindergarten is the free republic of childhood.

A deep feeling of the universal brotherhood of man—what is it but a true sense of our close filial union with God?

Man must be able to fail, in order to be good and virtuous; and he must be able to become a slave in order to be truly free.

My teachers are the children themselves, with all their purity, their innocence, their unconsciousness, and their irresistible claims; and I follow them like a faithful, trustful scholar.

A story told at the right time is like a looking-glass for the mind.

I wish to cultivate men who stand rooted in nature, with their feet in God’s earth, whose heads reach toward and look into the heavens; whose hearts unite the richly formed life of earth and nature, with the purity and peace of heaven—God’s earth and God’s heaven.

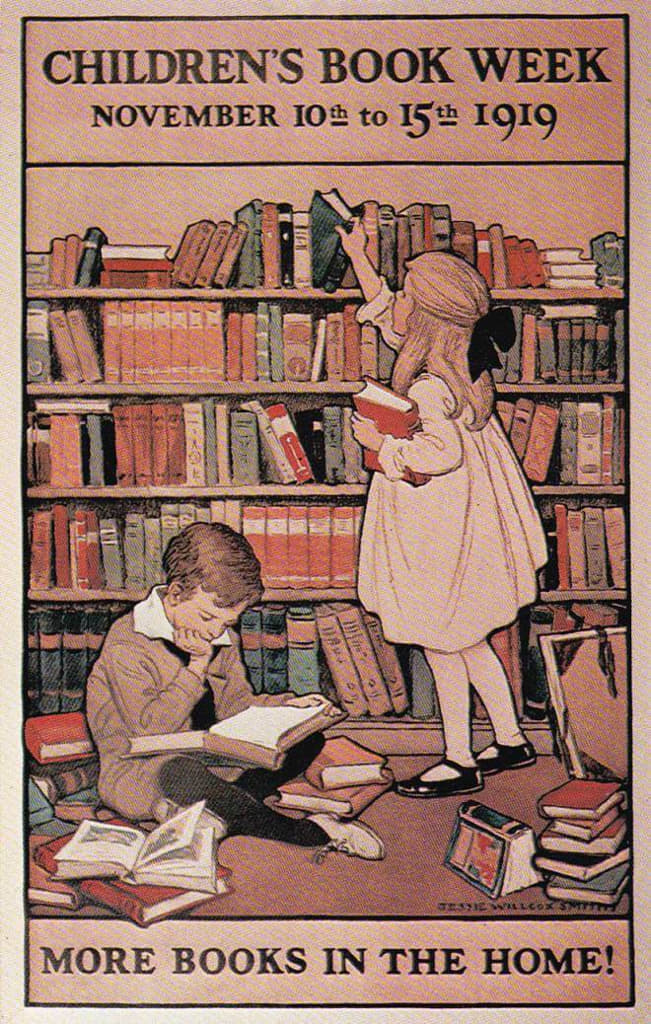

Featured: Poster for the American Library Association, by Jessie Willcox Smith, 1919.