After the conquest of Granada by the Catholic Monarchs on January 2, 1492, the Muslim population that remained in the old Nasrid kingdom was a constant source of problems because of their lack of integration. After the War of the Alpujarras, between 1568 and 1571, the Muslim population was dispersed throughout the other kingdoms of Spain, until its definitive expulsion in 1609.

The Ignatian Moriscos

During this long century, the attempts at evangelization multiplied; but the authentic conversions were always sporadic, and even less numerous were the converts who entered into religion. Two of them were Juan de Albotodo (1527-1578), and his disciple Ignacio de las Casas (1550-1608), both Jesuits, followers of the project of their founder, St. Ignatius of Loyola, who wanted to assign a large number of Moorish religious to the evangelization of North Africa.

Miguel Ángel García Olmo, PhD in Cultural Anthropology, lawyer and philologist, author, among other works, of Las razones de la Inquisición española (The Reasons for the Spanish Inquisition) has written an essay on both these Jesuits Moriscos, which won him the Pascual Tamburri Bariain 2021 Prize, an award that furthers the legacy of Pascual Tamburri Bariain, professor, intellectual and journalist from Navarre, who died prematurely in 2017, at the age of 47.

The essay, published in issue 228 of Razón Española (a magazine founded in 1983 by Gonzalo Fernández de la Mora), and entitled, “The Ignatian Moriscos,” highlights Fathers Albotodo and Las Casas for their powerful personality and apostolic constancy, but also as an example of “the poor harvest that the Church was able to reap after a century of exhausting and disheartening sowing in the hermetic field of the Moorish soul.”

The converts from Islam to Christianity had a double merit: not only did they have to face their communities of origin, but also the reticence and mistrust of the Spanish society of their time, obsessed with the cleanliness of blood due to the presence of the Judaizers. When they then entered religion, their natural desire was to preach among their brethren.

Standard Of Charity

Albotodo, son of Moors and grandson of Moors, well expressed his intention to “preach especially to Moriscos and Moors… and to give tidings of Our Lord Jesus Christ, who is not known,” in gratitude for the “so great mercy and benefit” that he had received from Him with the light of faith.

On feast days he gave such tiding, in Arabic, in the Albaicín of Granada, where there were six thousand new Christian homes, to whose children he taught the Christian doctrine. His preaching in the neighborhood, or in his missions in the Alpujarras shocked his listeners, particularly the women, whose conversion was fundamental because they were the ones who, in the discretion of the home, transmitted the Mohammedan beliefs from generation to generation.

Father Albotodo was also devoted to charity; and thanks to his efforts, a hospital for the poor and a school for children and adolescents was opened, sponsored by the famous Archbishop Pedro Guerrero, a prominent figure in the Council of Trent. In its heyday, it had 550 students.

But what was the fruit of such an enormous apostolic effort? García Olmo points out the contrast between the triumphalist letters sent to Rome and the “growing pessimism” in the face of the “sterility of the colossal effort” which did not bear fruit.

The Jesuits considered shutting everything down, but Albotodo did not give up (supported by St. Francis of Borgia) and remained as the only priest in the neighborhood, assisted by five Jesuit brothers, until the final farewell in 1569, when the War of the Alpujarras completely changed the relationship with the Muslim community.

Support For The Crown

This community, which a few years earlier had asked for Jesuits for the neighborhood, conceived a “bitter resentment” towards them, because the sons of St. Ignatius, who knew the reality they were facing, had approved the military actions of the Crown against the Moorish uprisings. They made an attempt on the life of Albotodo, who escaped unharmed; and on Christmas Eve 1568 the Muslims assaulted the Jesuits’ house looking for him to kill him, from which he escaped at the last moment.

Although he supported the repression of the Moorish uprisings, Father Albotodo protected his relatives and obtained from Don Juan de Austria, in command of the royal forces, guarantees for their lives.

He then devoted himself to other apostolic work, among the prisoners, where he stood out; and there is a record of at least one conversion, that of a Moor condemned to death and executed in 1573.

Christianity And Islam: An Impossible Convergence

Father Ignacio de las Casas, a disciple of Albotodo, continued his work, although in a very different style. If the master had done the work mainly through charity, Casas devoted himself to an effective public defense of his people. He did so without any relativism, because in the same way that he advocated a deep and orderly study of the Koran to better approach his followers, he encouraged—in his words—to “hate and abhor the sect of the perverse Muhammad.”

In fact, in the famous polemic of the Plomos del Sacromonte he opposed any compromise between Catholicism and Islam. In 1595 some pages were discovered in a strange Latin mixed with Arabic that pretended to be a fifth gospel, with supposed revelations of the Blessed Virgin and of the Apostle Saint James, looking for a compromise between the Christian faith and Mohammedan beliefs. A forgery—probably the work of elite Moors anxious to reduce the tension between both communities—but this work did not deceive Las Casas.

Even so, he sought compassion rather than confrontation, and did not hesitate to make in his letters and writings, explains García Olmo, “an emotional and at the same time reasoned vindication of the moral qualities treasured by the Moorish people.” At the same time, he denounced the contradictions of the assimilationist policies of the Crown and the Church, which combined mass baptisms with “isolation” and “contempt” for the neophytes.

Failure

Las Casas, like Albotodo, was motivated by a sincere desire for an authentic conversion, thanks to a true catechesis, instead of a policy of pacts that was satisfied with the purely external submission of the Moriscos, only to have to subdue them by force when, resentful of their own double life, they rebelled. He himself went to the King and the Pope to censure this way of acting.

The truth is that the evangelizing work of Albotodo and Casas did not obtain the expected results, because of the closed resistance of their recipients, who ended up seeing the Jesuits as mere agents of power to strip them of their identity and their traditions.

And both men also understood and supported the subsequent decisions of the Crown when that stubborn resistance translated into open insubordination, accompanied by crimes and martyrdoms against Christians. Both men were good and zealous shepherds of souls—souls of the people to whom they belonged by blood—but they did not hide from the danger of interior Islam as a cancer of Christianity, the people to whom they belonged by faith.

Carmelo López-Arias is a Spanish historian and writer. This article through the kind courtesy of Religión en Libertad.

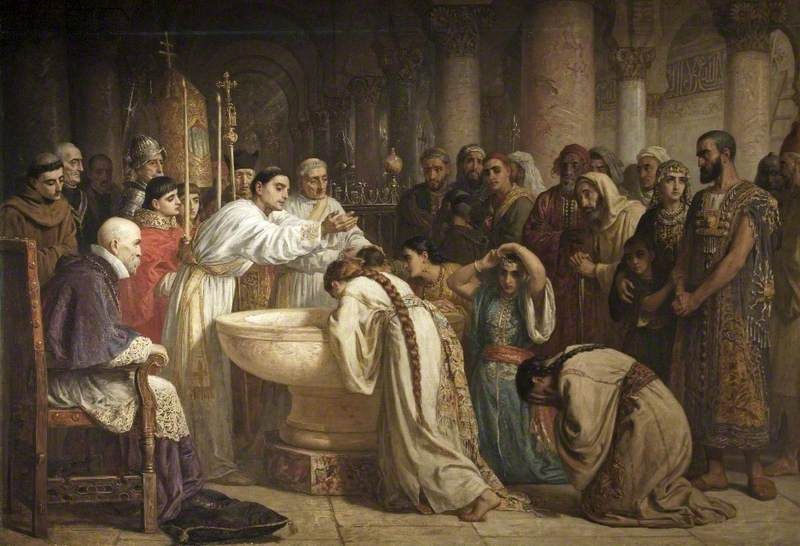

Featured image: “The Moorish Proselytes of Archbishop Ximenes, Granada, 1500,” by Edwin Long; painted in 1873.