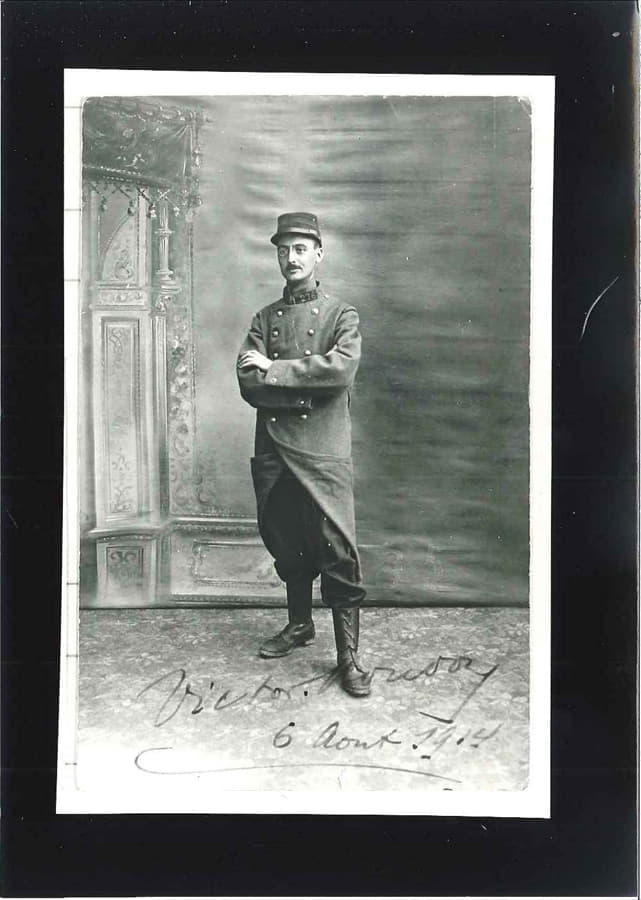

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the birth of Charles Péguy (1873—1914), and by coincidence, next year will mark the 109th anniversary of his death, when he was killed in action at Villeroy, one day before the Battle of the Marne. What follows is the Preface, written by Maurice Barrès (1862—1923), to a book of memoirs, (Avec Charles Péguy de la Lorraine à la Marne, aôut-septembre 1914, With Charles Péguy of Lorraine at the Marne, August-September 1914, published in 1916), by Sergeant Victor Boudon, who served under Lieutenant Péguy,

I adored Péguy. These feelings were reciprocal. He showed me a lot of friendship. You know the penchant he had for handing out roles, so like tasks, to each of his friends; which is quite evident in the extraordinary talks that the faithful Lotte noted. To all those who appreciated him, he intended to give a task in his life. In his eyes, I was a boss, an elder, an “old man” on whom he could rely. One day he said to me, “You are our patriarch.” I was astonished.

I can still hear him, I can still see him, as he was that day, arriving in Neuilly, as usual, in his devilish great coat, his eyes full of fire and insight, but a little turned inward and intent on his own concerns. His bushy, ageless face, radiant with the youth of children and the bonhomie of old people, and thus casting me, with a single word, quite unexpectedly, into the cellars of the deepest old age, as much as into the grave. A patriarch! How fast life goes by!

He named me thus out of affection and to mark out my path for me. I was a subscriber to the Cahiers; the first one; I had announced and celebrated the Joan of Arc. If it had been up to me, he would have had the great prize of literature at the Academy. But all the same, we had obtained for him another prize, an equivalent—he gave a part of his work to my publisher and friend, M. Emile Paul. Then, as he reported in his Entretiens avec Lotte (Talks with Lotte), he and I dreamed that he would enter the Academy quickly.

He was happy with all this; but all this is nothing but trifles and dried grass compared to the real service that I was able to render him, comparable to a source of living water that I was allowed to make gush out and that forever preserves him from death.

On December 12, 1914, a soldier wrote to me from hospital no. 17, in Laval: “I had the honor of fighting alongside and under the command of Charles Péguy, whose glorious death on the field of honor you have exalted. He was killed on September 5th, at Villeroy, next to me, while we were marching to the assault of the German positions.”

Just imagine my emotions of pleasure and piety. What! A man wounded at the Ourcq, struck the day after Péguy fell, was able to speak! On the 26th of the same month, without making a single change, I printed Victor Boudon’s admirable account. Two months later, on February 27, 1915, he put me in a position to offer a complement of the highest importance. Today, here he is publishing his incomparable deposition in all its extent and scrupulous sincerity.

With Péguy from Lorraine to the Marne August-September 1914. “These simple pages,” he says in his introductory dedication, “are the modest testimony of a soldier, to the memory of Charles Péguy, his leaders, his brothers in arms, the glorious dead of the 276th, all those who, by their heroic sacrifice, saved Paris and France in September 1914.” And this book, as Anatole France had already done with his precious collection, Sur la Voie Glorieuse (On the Path of Glory), Victor Boudon, wounded in the war, expressly notes that it will be sold “for the benefit of the Fédération Nationale & Assistance aux Mutilés des Armées de Terre et de Mer” (National Federation and Assistance to the Wounded of the Armies of Land and Sea).

May we add our thanks to the gratitude of all. What is this noble witness? What is the merit of this companion who will never leave Péguy down the centuries?

When the war called him to the regiment, Victor Boudon was a salesman. Before that, still very young, he had worked as secretary to Francis de Pressensé at the Human Rights League. That is to say that no one more than he would have been able to immediately become intoxicated with our friend’s theories on the Mystery of the Revolution and of the Affair, and very quickly with his theories on the Mystery of Joan of Arc. But, curiously enough, Boudon was unaware of these meditations when the chance of mobilization put him under Péguy’s command in August 1914, in the 276th Infantry Reserve Regiment: “I knew,” he told me, “that Péguy was writing the Cahiers de la Quinzaine. I had read a few issues, at the time of the Affair; but since then nothing.”

He regrets not having “exchanged ideas” with Péguy. “I had my place. We hardly spoke. And then it was all so short, so full of fatigue, of events. Yes, I promised myself on occasion to ask him questions and to listen to him.”

Let Boudon rest assured. He knows a truer, more beautiful, more eternal Péguy than the one we used to see; and his testimony brings us the Charles Péguy of eternity.

I am not simply saying that in this Memorial you will see Péguy standing upright in the midst of his men and as posterity welcomes him. He will appear to you in the course of these thirty days of war as a man of the oldest France; and you will see in action what you have already distinguished in Péguy’s geniality, a contemporary of Joinville and Joan of Arc—in short, the Frenchman of eternal France.

Keep in mind that there are, in these pages written by this Parisian of 1916, passages which seem to be of “the loyal servant” of Bayard type (See the place given at night to a poor woman, on page 94).

Such scenes, so pure and, so to speak, holy, are mixed in with other scenes that are far cruder and which, moreover, show prodigiously innocent souls. That is the beauty of this book; one sees in all its reality the swarming of life, the common crowd not yet quite become the warlike troop, the sancta plebs Dei, so dear to the historians of the Crusades.

There was, in the first psychology of our armies of 1914, a shade of sansculottism. A combatant who knew how to observe said to me: “At the beginning of the campaign, I was often struck by the unabashed sansculotte attitude with which the mobilized workers and peasants pretended to maintain, in front of the Kaiser and his henchmen, the right they recognized, to have neither God nor master, to practice a cordial alcoholism and a cheerful anticlericalism as they pleased.”

To what extent had this initial disposition changed? What is the truth behind the stupor in which some seemed to live, the peaceful obstinacy of the majority, the indifference to danger of the best, the docility of most of the others?

At present, there is something uniform in many people, with very simple, very primitive feelings, from which emerge above all resentment against the henchmen and exploiters and a certain obsession developed by solitude. Under the influence of suffering, sacrifice, in the gravity of this terrible or tedious life, in short, with experience, everything has changed. It seems that other combinations of qualities, virtues and defects have forced themselves on all, on the professionals as well as on the soldiers coming from the civilian world. Even the small de facto aristocracies that provided the framework have found their value in a different order of magnitude from the one they initially placed as the highest.

But the army that Péguy saw was the army of the early days, which had not yet undergone the crushing and recasting that the war imposed on it, and in which the superb elements of the suburbs and the professional military elements were juxtaposed rather than amalgamated.

Read, at the very beginning of Boudon’s account, this very characteristic scene of the brave mobilized drunkard who quarrels with an officer on the departure platform. Everything goes wrong, but Péguy intervenes with the tone of a Parigot, and the amazed man says: “For a lieutenant, he is a nice guy.”

Throughout the thirty days that Boudon recounts, you will constantly find this popular vein. Observe, for example, with a bit of divination, the feelings inspired in these workers of Belleville and Bercy, in these peasants of Seine-et-Marne, by Captain Guérin, a great figure of an older, more austere model, less completely accessible to those who from the first moment knew how to see in Péguy “a nice guy.” Captain Guérin, a professional of purely military discipline and science, embodied doctrine and tradition. Whether or not he is “a nice guy,” I will let you decide, but that he is a guy, I mean a man who is strongly drawn and who has authority as a model. Péguy knows it. Péguy notices it; accepts the exemplary lesson of a Guérin against whom native independence, more warrior-like than military, is first raised.

Péguy, and this is his incomparable value, is placed at the confluence—do I make myself heard?—of our traditional and revolutionary forces; he can be at the same time the man of doctrine and of the most ardent individual excitations. Our friend, those who know his work and his nature realize it easily, was capable, better than anyone, of recognizing and using the bold independence and the rich humanity of these suburbanites of Paris, of these farmers of Crécy and Voulangis, and making a noble imagination out of them. Son of a worker, grandson of a peasant, given a scholarship, proud of his poverty, regarding himself a journeyman typographer even more than a man of letters, all nourished by Joinville and Joan of Arc, and added to that the infinitely noble and warm heart, Péguy always wanted to operate by way of friendship, without disciplinary measures, for the benefit of a higher friendship, for the benefit of the fatherland. Péguy marched off with his brothers.

No one had the understanding of the companionship of arms, in the old sense of our country, more than him. In the old days, in the France of the Middle Ages, what constituted the political system, was not the fief, the land, the real (landed) relationship, it was the personal relationship. What wove together the threads of the feudal fabric was the attachment of man to man, the faith. And the same need to support the relations of leader to soldier on a free acceptance, on a voluntarily consented fidelity, subsists in our peasants, in our workers, in the bottom of all our hearts. In the past, between leaders and companions, or between companions of the same leader, pacts were formed with extreme energy which sometimes amounted to brotherhood: Oliver and Roland, Amis and Amile, Ogier and Oberon, Clisson and du Guesclin. You will recall the beautiful words of the agreement that Bertrand du Duesclin and Olivier Clisson concluded, putting nothing above their friendship but their loyalty to the king, that is to say, to their country: “Know that… we belong and we will always belong to you against all those who may live or die, except the king of France… and we promise to ally and support you with all our might… Item, we want and agree that of all the profits and rights that may come and fall to us from here on out, you will have half entirely. Item, we will keep your own body at our disposal, as our brother… All which things we swear on the holy gospels of God, corporally touched by us, and each of us and by the times and oaths of our bodies given to each other.” Well! Our Péguy spent his life sealing similar pacts with Joseph Lotte, Charles de Peslouan, the Tharauds, Claude Casimir-Périer, Daniel Halévy, the two Laurens, Suarès, Julien Benda, Moselly, Lavergne, Eddy Marix, Louis Gillet, and with all the regulars of the little store in front of the Sorbonne, or more simply with the subscribers to the Cahiers de la Quinzaine; and then, a little bit further away from this portico open to all the winds, with Monseigneur Batiffol, Dom Baillet, the pastor Roberty, Georges Goyau and Madame Goyau. And then he sealed this pact with each of the “guys,” as he liked to say, whom he led to war.

It is not a game to bring Péguy closer to the noble men of old. If we loved his character with respect, even in his excessive originalities, at the time when he was not yet a hero of France, it is because we recognized in him the ancient virtues that he took as models. And these men of the people, mobilized workers and peasants, if they took to him immediately, it was because they too belonged to olden times; I mean they carried proud and good instincts in them, always vigorous, which could not be better disciplined than by an attachment of man to man.

Victor Boudon has added to his Memorial the letters that Péguy, during his month of war, wrote to his family and friends. Precious treasure. One seeks there what the hero thought. These quick writings are not enough. I give you something better. What Péguy thinks, or rather what forms in his conscience, deeper than his clear thoughts, what animates and obliges him, you will know by meditating on the great book that we have and that he certainly knew, loved and revered. It is Joinville who speaks. He says: “The Sire of Bourlémont, may God bless him! declared to me when I went overseas: You go overseas; beware of returning, for no knight, neither poor nor rich, can return, unless he is disgraced, if he leaves in the hands of the Saracens the little people of Our Lord, in whose company he has gone.”

Thus thought Péguy. And now that you know the warm, animating thought that places him in the direct line of eternal France, watch him act and die as portrayed by his true witness.

Heureux ceux qui sonl morts dans les grandes batailles,

Couchés dessus le sol à la face de Dieu.

Heureux ceux qui sonl morts sur un dernier haul lieu,

Parmi lout l’appareil des grandes funérailles,

Heureux ceux qui sont morts, car ils sont retournés

Dans la première argile et la première terre.

Heureux ceux qui sont morts dans une juste guerre,

Heureux les épis murs et les blés moissonnés.

(Charles Péguy, “Prière pour nous autres charnels,” 1913).

Blessed are they who died in great battles,

Laid upon the soil in the face of God.

Blessed they who died on the last high place,

Amidst all the pomp of grand funerals.

Blessed they who died, for they have returned

To the very first clay and the first earth.

Blessed are they who died in a just war,

Blessed the ears ripened and the wheat reaped.

(Charles Péguy, “Prayer for us Mortals,” 1913).