The disintegration of class has induced the expansion of envy, which provides ample fuel for the flame of ‘equal opportunity’… Education in the modern sense implies a disintegrated society, in which it has come to be assumed that there must be one measure of education according to which everyone is educated simply more or less. (T. S. Eliot, Notes Toward the Definition of Culture).

1.

Even the greatest defenders of equality are not advocating the idea of equality of outcome. They know that at the end of the day, the result of our work cannot be equally rewarded. And it is not because of anyone’s malice or arbitrariness. Our moral intuition tells us that rewarding a gifted and hard-working person and a lazy and untalented one the same way is wrong. Reward is linked to performance and excellence. Equality of outcome would kill both and thus violate our sense of justice.

In the face of this, instead of promoting social policies that would aim at equality of outcome, it became fashionable to advocate the idea of equality of opportunity. We do it not because the latter idea is sounder, but because it covers more sufficiently the sad truth about inequality between us and the structure of the world around us.

Does a farmer in Arizona or Nevada have equal opportunity to raise an equally rich crop as a farmer in New Jersey (a garden state)? Does a fisherman in Arctic waters have an equal chance of catching fish as the one in warmer waters? How can one create equal opportunities for children whose passions in life are farming or fishing, and yet who do not live in the same place – a place blessed with good soil and climate, or one near waters with a superabundance of fish? One could bring more fertile soil from New Jersey to Arizona or Nevada at a great expense, though it would be wasted there because of the differences in climate.

However, someone who promotes equality of opportunity makes a less radical claim. He claims that Mr. Brown, who lives in the same environment or place, is worse off than Mr. Smith because he did not have the same opportunities. However, the supposition is unverifiable. Only by watching Mr. Brown’s life in a parallel universe, where he and Mr. Smith had equal opportunity and became equally successful, could we claim the truth of the assertion that if everyone is given the same chance, everyone will succeed. All we can say in our universe is that we will never know where Mr. Brown would be in life should he have been given equal opportunity to everything. Because we accept the premise that “we will never know,” we succumb to the rhetoric of those who advocate the policy of equality of opportunities, and hope for the best (“let’s hope, that for some reason, they fail to implement it”).

In ordinary language, such proposals are formulated in a language that has emotional appeal: How can you be so heartless and deny Mrs. Brown’s child – our Mr. Brown – the same opportunities! Besides, how do you know that Brown, Jr. will not become another Michelangelo, or another Marie Skłodowska-Curie? Not to create equal opportunities is to kill the genius before he was ever born. This form of reasoning is fuzzy, and it rests on the false premise that there is a correlation between genius and equality of chances. A survey of historical figures whom we call geniuses does not provide any evidence for such claim.

Human beings, like soil and climate, are different – not equally gifted, not equally ambitious, not equally motived – and it is unlikely that equal opportunities for all would benefit everyone; or, sadly, that most of us would like to be anything other than what we are. Most resources would be simply wasted.

If the proponents of equality admit that the implementation of perfect equality of opportunities is impossible, we should at least insist that they make it clear what the end of such policies truly is?

Alas, this remains unspecified. However, the language the partisans of equality use provides us with clues. It is the language of “minimum wage” which should suffice for “dignified” existence. However, it would be in vain to look for the definition of “dignified life” in the politicians’ pronouncements; but the language of “minimum wage” suggests that everybody should be able to afford very many things that only a hard-working middle-class can afford today. Accordingly, a “dignified life” means that the purse of a minimum-wage earner should have similar purchasing power to that of a hard-working and educated professional.

To make things even more equal, in the last few years we hear more and about Universal Basic Income (UBI). What it means is that you will not have to work, unless you want; and the government will give you money for free. This is what Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez, in fact, said. All such proposals suggest that the effort to become educated so that you can have a better life is optional; and since everyone should have a right to live a “dignified life,” someone else is duty-bound to subsidize your dignity.

2.

The Greeks were the first to provide us with a very important theoretical insight into the nature of work. As Aristotle noticed, “We work in order not to work;” that is, work is the condition of free time. Material prosperity, the Greeks thought, is the foundation of leisure – time freed from labor. Given primitive conditions of labor and production in ancient and pre-Modern (pre-Industrial Revolution) societies, slavery and serfdom – the labor of some – was essential for leisure of others.

There is more to it: Leisure was the condition of being free. But the Greeks also drew a very important conclusion – freedom, which some enjoy, creates conditions conducive to the development of Culture. Only a free man can afford to engage in cultural activities, which a man who must devote his time to labor cannot. And since the efficiency of labor in pre-modern societies was low, the long hours devoted to labor left virtually no time for other activities. In the words of Oscar Wilde, slavery was the price we paid for civilization.

It would be naive to believe that all free Greeks were aware of this and considered their free time to be something that they must use for cultural activities. Aristotle’s discussion in Book I of his Nichomachean Ethics is a clear indication that he understood that most people value what he terms apoloustic life, life according to pleasure, life that most of us live. But this kind of life, he argued, cannot bring about happiness, because it is dependent on too many external factors. Theoretical life is the highest form of happiness, and we can live it only “in so far as there is something divine in us.” Notwithstanding all the difficulties of how to balance practical and theoretical sides of life, Aristotle was right to draw our attention to the theoretical aspect of human existence that is responsible for most of our non-practical, intellectual and creative endeavors.

The partisans of equal opportunity, on the other hand, believe that the source of misery of today’s underdogs is the lack of material resources, and only if we transfer enough money to the poor, they will have more time and their aspirations will change.

This is what Socialism was to bring about. Karl Marx who knew about the nature of labor probably more than anyone in 19th-century, understood this idea very well. Marx imagined Socialism to be the place where leisure, thanks to technological advancement, is no longer the luxury which only small part of the population can enjoy, but which can be expanded to the masses. Thus, in a Socialist state, everyone would be free to develop his humanistic side and become something like a “renaissance man:”

For as soon as the distribution of labour comes into being, each man has a particular, exclusive sphere of activity, which is forced upon him and from which he cannot escape. He is a hunter, a fisherman, a herdsman, or a critical critic, and must remain so if he does not want to lose his means of livelihood; while in communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic.

Nothing in the political pronouncements of our democratic-socialist activists and politicians (e.g., Bernie Sanders and Alexandra Ocasio Cortez in America who pushed the Democratic Party in a semi-socialist direction) suggests that they want to implement Marx’s idea of human development. Unlike the Greeks and Marx who understood the purpose of human life to be something other than animal-like vulgar existence, they do not understand the goal of leisure and the meaning of culture either. Bernie Sanders and the Democratic Party’s “socialist revolution” is the apoloustic revolution without the Marxian-Aristotelian humanistic aspect. Not a single proposition that we hear from the Democrats points in the direction of ennobling the destitute masses.

The post-1960s America (and other Western countries) created all kinds of social programs, which, however well-intended and badly needed then, over time, created a class of people who did not have to work for generations. For all intents and purposes, it was a new leisure class: The class whose members receive free housing, food-stamps, child support, disability assistance, energy subsidies, free health-care, and free education. And because they did not have to work, they had abundance of free time. However, contrary to what Marx expected, this class did not become a powerhouse of culture. It became a place from which all traces of culture have been erased, a place where one peddles drugs, where crime-rate is higher than anywhere else, and where education is in shambles.

In contrast, the aristocracies of the 16th through to the 19th-centuries, whose existence was also “subsidized” by the labor of others, created enormous volume of cultural products – including cultural and scientific societies, literary salons and clubs – and even if we today consider some of their habits, customs, activities as silly or incomprehensible, one thing needs to be said: Most of them actively participated in, created, or, following in the footsteps of the Roman Maecenas, sponsored the creative work of the hard-laboring artists. Had they had no real interest in what was presented to them by artists, poets, writers, and philosophers, whose works were an expression of the highest aspirations of human spirit, nothing that we consider culture would have been created.

It is important to ponder on, and understand why the two cases are so different. The most likely explanation is that only a small minority among us was and ever will be interested in “dignified life.” Marx was a great believer in humanity, thinking that once wealth, which creates leisure, is available to the working class, it will change their lives in a fundamental way.

There is no question that material prosperity is today higher than ever before; but can one say the same about higher human aspirations? There is nothing in Aristotle’s discussion of how people live that made him have second thoughts that the majority of people will want to change their way of life. He never entertained political and social proposals that could elevate the masses.

What turned out to be true is that some of us (a relatively small percentage in every society), who by past centuries criteria would belong to the laboring-class, with no leisure to develop a more noble side, are interested in doing it now. Resources and considerable leisure that we enjoy now is something that belonged only to the aristocracy of old. This was already true in the early decades of the 20th-century. However, as Ortega y Gasset noticed, in his The Revolt of the Masses and The Mission of the University, the most distinguishing feature of the new mass man is his mental primitivism – lack of understanding of culture as a complex system of ideas which one must understand and renew in each generation for civilization to go on living. This lack of understanding manifests itself in being “ungrateful” and expecting that benefits will always be there. To the mass man, civilization is like a vending machine. However, this machine to operate needs maintenance. The new man does not understand it.

3.

If we are to consider the idea of equality of opportunity as a serious social program, equal opportunities should be created only for those who have demonstrated serious aptitude and effort in taking advantage of the opportunities afforded them by working members of society.

No one should demand that anyone pay the expenses of another. Only immediate family members are morally obliged to help their next of kin; similarly, friends should be able to rely on each other – without this, there is no friendship. Besides, no society can afford the exuberant costs to create equal opportunities for all its members without a sense of deep moral obligation; and no society should bear the burden of equal opportunities for all, only to realize that, at the end of the day, few persons out of the entire population will profit from these opportunities, or even bother to take advantage of them. Such policies are neither reasonable nor economically justifiable.

Given the limited resources that a society has to help others, the resources should be allocated wisely. This means, firstly, that they should be spent on those who are most likely to take advantage of them (they are the ones who need them). Secondly, we must have a very clear understanding of the exact purpose of such policies. Unless the government, which shapes such policies, provides a persuasive explanation that such policies are good for society, and that they actually work, the government engages in legalized theft, taking money from the productive class only to waste it on others in the name of ideological whims.

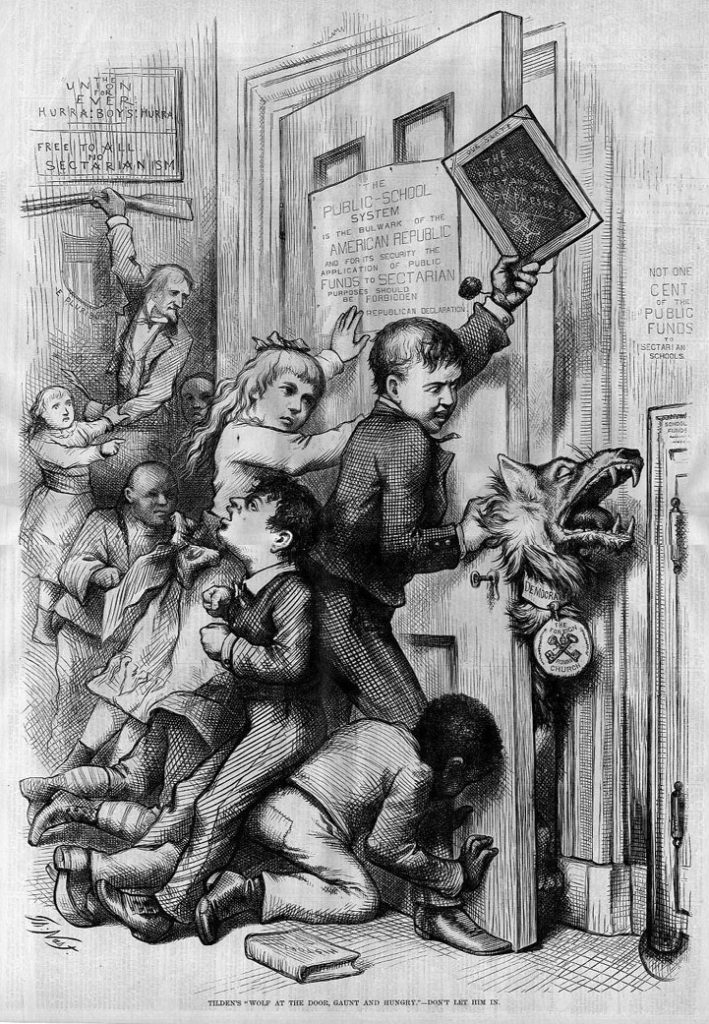

One could claim, however, and such claims have been made (for example, by John Stuart Mill, who advocated a number of reasonable social reforms proposals), that it is expedient for a society to have, for example, an educated citizenry instead of an uneducated one. An educated society is more likely to be affluent, is less crime-ridden, politically informed, gentler, and more appreciative of culture than a society wherein the majority are uneducated.

This is true, but it must be remembered that social expediency is not the same as possessing a right to something at the expense of another. A right is a claim to something, the possession of which is not contingent on anything else. I can claim, for example, that I have a right to life (that is, no one can deprive me of life without a legal due process), but I cannot claim to have a right to education, since it is connected with considerable costs borne by others. (Not only would it be, but it really is, futile for someone in a poor country – most African and many Asian ones – to demand decent education when there is no educational infrastructure). Such claims can be made in countries which have reached a certain level of civilizational and economic development, and so have created wealth that makes it possible for everyone to go to school. But this still does not make my claims fully justified to consider it a right.

I have an implicit right to demand that my parents do whatever is in their power to feed and educate me; but I do not have the same right to make of others (society) to do the same for me. Similarly, my daughter can demand that I do this for her; but if any of my daughter’s friends were to demand this from me, their demand should fall on deaf ears. Her friend cannot file a legal claim which accuses me of not fulfilling my duty by not giving her the lunch or small allowance that I gave my daughter. Any legal or formal claim on others has its limitations; whereas a moral one stems from the sense of parental duty.

4.

All three monotheistic religions – Judaism, Christianity, Islam – have a built-in obligation to help others. It is called “giving alms.” Christianity made it more universal than Judaism and Islam. In the words of Saint Paul, “there is no Greek or Jew” (we are one human family). But giving alms is not the same as creating state policy of equal opportunities above the level of giving others food and helping with basic needs. It would be silly to think that my obligation to give alms means giving the poor crevettes, caviar, and a steak with a nice bottle of Bordeaux for dinner. Helping others has its limits; and it does not mean that we all have equal share in the available resources created by others.

Given the decline of religious participation, the State in the 20th-century had to take over many of the obligations which in previous centuries were fulfilled by the Church. Today’s governments are heirs to the religious institutions, though without having any moral authority, and therefore they do not cause us to feel that we owe anyone anything.

Imposition of taxation and the transfer of wealth from the richer part of the population onto the poorer is the secularized version of giving alms. Its downside is that the government claims your wealth without making reciprocal demand that the poor be grateful for it. What is more, yesterday’s poor, as Nietzsche and Ortega would have it, are today’s social justice warriors who demand your wealth in the language of equality and opportunities for all. (The prime example of it is the attitude of Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez.) Unlike in the past, when the poor had to ask the priest in their parish to give them alms that others voluntarily left for them, the 21st-century State makes impersonal computer transfer of money, which covers the poor’s shame for living off others, and demands nothing in return. This lack of gratitude is a characteristic feature of the mass man.

5.

There is no question that education is a path to success in life, and everybody who wants to be successful must be educated. But equality of opportunities says nothing about the amount or kind of education that makes you successful.

In his Notes Towards the Definition of Culture (1948; chapter VI), T. S. Eliot noticed something that is worth reflecting on. Ever since the disintegration of the class system (which coincided with the advent of egalitarianism), we have been using a strange language of “undereducation.” One can point to someone and say, “He is half-educated” or “undereducated.” This is a strange language indeed. “Undereducated” in what sense? Our “undereducated” person can be an auto-mechanic, a crane operator, a nurse, a bricklayer, a bus driver, or even an insurance agent or CEO. He does what he does successfully, and yet he is purportedly “undereducated.”

As T. S. Eliot noticed, it would have never occurred to someone in 17th- or 18th-centuries to say that the baker, the brewer or the shepherd is “undereducated.” This example shows that education in this context is connected to the idea of something that goes beyond the vocational skills which one has; and the vocational skills indicated the class belonging. Once the classes, which defined cultural level of each person, and thus education, disintegrated, the same level of education was being applied to everyone; and it was not professional education.

Education meant cultural level. And since the litmus test of education was (High) Culture, the culture of the leisure class or classes, undereducation was the term applied to everyone who fell below that level.

Socialism and democracy tried to make culture available to everyone, and to disseminate it among the masses. However, the attempt was (and still is) only partly successful. Only a small number of people, who by old standards did not belong to a noble class which had access to culture (which was the culture the aristocratic class created), developed a taste for, and appreciation of, it.

What was responsible for the success of cultural transmission was the opening of prestigious places of learning (like Oxford and Cambridge in England) to students from all walks of life. But it was open only to those who met high educational requirements. (The story of A. L. Rowse, a boy from Cornwell, who went to Oxford and became a fellow in the prestigious All Souls College, is one of the greatest testimonies that culture can be transmitted to the lower classes).

This idea was not only sound – it was probably the most successful social experiments in a democracy: A way of creating natural elites. Elites, by definition, are small groups, composed of individuals with higher scholastic aptitude. The English educational experiment to open prestigious schools to children of humble background is probably the most any society can hope for. Today’s rebellion against Cambridge, Oxford, and Ivy League universities in the U.S., demands that old acceptance standards be waved or abolished, is an indication that the Ortegian revolt of the masses is very real, and will stop at nothing but total destruction of cultural heritage.

To be sure, Culture (capital C) is the term that social justice warriors never use, are not interested in, and to the extent to which they understand its meaning, they mean such activities as vulgar pop or rap music. They are the products of the “undereducated,” uncultured individuals who are unlikely to appreciate the creative work of Titian, Duerer, Tintoretto, Moliere, Racine, Marlowe, Goethe, or Byron.

If so, what equal opportunity do they demand for the “undereducated,” if it is not their goal to provide the underdogs with the education that would allow them to take their gutter lyrics to the level of Rossini or Wagner? Many of them may never get there, but the few who are exposed to Culture have a better chance of leaving the gutter when they experience something beautiful and sublime.

6.

The goal of the partisans of the idea of equal opportunity, one can still argue, is not to get anyone to the same creative level as Chopin or Mozart, but to foster their economic success, so that they can live a “dignified life.” In one of the most memorable passages, in his The Wealth of Nations (1776), Adam Smith offered an ingenious explanation as to what is necessary for lower classes to succeed:

The difference of natural talents in different men, is, in reality, much less than we are aware of; and the very different genius which appears to distinguish men of different professions, when grown up to maturity, is not upon many occasions so much the cause, as the effect of the division of labour. The difference between the most dissimilar characters, between a philosopher and a common street porter, for example, seems to arise not so much from nature, as from habit, custom, and education. When they came in to the world, and for the first six or eight years of their existence, they were, perhaps, very much alike, and neither their parents nor playfellows could perceive any remarkable difference. About that age, or soon after, they come to be employed in very different occupations. The difference of talents comes then to be taken notice of, and widens by degrees, till at last the vanity of the philosopher is willing to acknowledge scarce any resemblance. But without the disposition to truck, barter, and exchange, every man must have procured to himself every necessary and conveniency of life which he wanted. All must have had the same duties to perform, and the same work to do, and there could have been no such difference of employment as could alone give occasion to any great difference of talents.

Accordingly, the difference in social and financial status between people aged 46 or 48 is not due to the ingenuity of some and a lack thereof on the part of others who are less successful. As Smith makes clear, when the same people were children – 6 or 8 – they displayed no differences; and yet, forty years later, all of them found themselves on different social and financial levels. Why?

The first level of explanation deals with principles of economy (division of labor): Members of different professions are paid differently. A doctor or lawyer is paid more than a teacher, a clerk, or someone who works in a Starbucks, and so on. The differences between professions have roots in the years spent on acquiring the knowledge requisite to become a doctor, lawyer, engineer, and so on. One must also note also that the father of modern economics is not considering here the case of geniuses, but the average person – and every average person, thanks to education, can become a lawyer, a doctor, or an engineer. (One can leave aside, of course, natural predilections for some professions).

If so, why can’t we all become lawyers, doctors, engineers, that is, members of lucrative professions? The key to success, as Smith claims, is: Custom, habit, education. It is very likely that a child who is accustomed to waking up early, reviewing his homework, reading a lot, and is disciplined, will earn high grades, will become a doctor, a lawyer, or an engineer; whereas a child who neglects his study and lacks discipline will not be eligible for such occupations.

“But he is only a child,” someone may exclaim, and so “it is not his fault.” True, it is contingent upon the parents to train the child for the responsibility which he has yet to understand the significance of. Once we accept this simple premise, we can explain the situation of the underclass and the lack of success of its members.

The problem lies with the family and Culture – the habits and customs with which children grow up. Custom and habit are part of Culture, and not all Cultures are equally geared to inculcate habits that are conducive to intellectual development; some never developed to the point where one realizes that the abstract way of thinking is the condition of all the practical fruits that we all enjoy. This was one of the greatest European discoveries, which we can read about in Descartes’ Discourse on the Method of Directing One’s Mind in the Sciences. The social and economic success of the Jews and Asians in the modern world tells us everything we need to know about the love of reading and work ethic that are integral to success.

7.

Those who demand that all children have equal opportunities should first demand equal responsibility from all parents, each having an equal understanding of the importance of education and discipline. Parents are part of the equation. The second part is schools, and few of them have excellent or even good teachers. It is possible to have lousy parents and good teachers, and the other way around. But having lousy parents and lousy teachers is a disaster, and it is becoming a norm in America and other Western democracies.

The partisans of equal opportunities hardly ever blame the parents or single parenthood. They prefer to devolve parental responsibility for their children on the State, and then go on to blame the State for not doing enough to “create equal opportunities.” Such a situation creates a vicious circle, which we can break only if we demand that the State return the children to parents, that it stay away from them and the parents. When then the parents know that raising children is their responsibility, they will start doing their job. When parents are in full possession of children, they, too, will stop blaming schools. Education can be a path to success only if we the schools teach something worth knowing, something that is culturally relevant, and something that inculcates serious intellectual skills.

Last but not least, opportunities must assume an institutional form: Good and prestigious schools, scholarships and fellowships in institutions wherein they can develop their interests and talents, and, most importantly, where they can compete for the highest awards and places in society.

Such a society, of course, is one which understands and accepts the meaning of social and educational hierarchy and benefits which stem from relative inequality. It is not a society based on artificiality of social distinctions, but on natural talents.

Are the social justice warriors ready to swallow this bitter truth that elites do not have to have the old aristocratic titles? Nature confers them upon some of us. It is through our individual effort that we reach for them.

Zbigniew Janowski is the author of Cartesian Theodicy: Descartes’ Quest for Certitude, Index Augustino-Cartésien, Agamemnon’s Tomb: Polish Oresteia (with Catherine O’Neil), How To Read Descartes’ Meditations. He also is the editor of Leszek Kolakowski’s My Correct Views on Everything, The Two Eyes of Spinoza and Other Essays on Philosophers, John Stuart Mill: On Democracy, Freedom and Government & Other Selected Writings. His new book, Homo Americanus: Rise of Democratic Totalitarianism in America, will be published in 2021.

The image shows, “The Flute Concert of Fredrick the Great at Sanssouci,” painted by Adolph von Menzel, ca, 1850-1852