1. Is Operation Z (The Invasion Of Ukraine) Explicable By “Putin Is Evil?”

I cannot agree with what seems to be the dominant explanation in the West that the Russian invasion of Ukraine occurred because Putin is evil. The ‘explanation’ is usually accompanied by claims that Putin is a megalomaniac and a Russian criminal; that his rulership lacks all legitimacy; that Ukrainians are the victims of his overriding ambition to restore Russia’s imperial place in the world; and that Putin is pushing the world to the brink of a third world war and hence must be stopped.

“What are we going to do about Putin?” as an old friend, in her late sixties, full of existential distress and brimming with moral fervor, exclaimed at a recent lunch. The same sentiments have also been repeated by scholars I admire deeply and have often found common cause with, in this very magazine. Thus, in an email chain I am part of, a historian, whom I consider one of the finest of our times, wrote in support of Ryszard Legutko’s condemnation of Putin in the European Parliament that he spoke “for all of us.” Given that I have recently written very enthusiastically on Legutko’s book on freedom here in the Postil, as well as having written an open letter condemning his appalling treatment at the hands of his fellow colleagues and students at his university, I wish that I did see things like him. But I cannot unsee what I see, and what I see comes from my readings and thought gathered over my adult life as a university teacher, where amongst other things, I taught International Relations.

Likewise, the very friend who introduced me to the Postil, and whose writings I have also applauded in these pages, Zbigniew Janowski, sent me his essay, “Ukraine And The West’s National Interest,” about the Ukraine war for comment. That and the request by another friend to share my take on this war have led me to set out my considerations.

War today is mass death, and horrific suffering, but I find all of the above “diagnosis,” to put it mildly, not only lacking in analytical seriousness but contributing to the mindset that has cried out in support of what—each and every time—have turned out to be disastrous military interventions which have only added chaos in regions which were bad enough before the toppling of regimes said to be guilty of “killing their own people”—a turn of phrase that people utter with such seriousness, as if its very formulation gives the situation a special kind of moral significance that we might otherwise be silly enough to conflate with any other kind of mass killing.

Thus, it is now that the people wanting to line up to morally address this geopolitical tragedy—why I formulate it thus shall become evident—have mostly been silent on Libya, Syria, and Yemen. Many, though far from all, who want NATO to “teach Putin a lesson” (said at the same lunch, where the woman’s husband squared up, “Putin is a bully who must be taught a lesson”) had also supported the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. I confess to having been ambivalent back then—in the case of Iraq, at least when it seemed that the CIA had definite proof about the WMD’s; and now seeing I was utterly wrong to believe that these operations were, at best, anything more than massive strategic blunders (leaving aside the whole “blood for oil” dimensions) that made things far worse than they were—and has only highlighted the deficiencies of the armed forces of the West.

This “essay”—if essay it be—is really a collection of considerations that bring together aspects of the tumult of the times which most would think irrelevant—and they are certainly irrelevant to the narrative-thematics mentioned above—but which for me are critical for any serious response to the war. It is a response that eschews the search for a single cause—because, like everything historically important, such searches are as futile as they are distracting and wrong-headed. That means that it is also not a search for moral culpability as such—for as is very evident to me and as I shall lay out, there is plenty of culpability to go around—though it does seem that plenty of people, including journalists, are either ignorant of, or silent about, all matter of circumstances and players that are pertinent to the disaster of this war. Geopolitical questions are never adequately answered by “He did it!” And yes of course Putin ordered the invasion. But the question that must always be posed to an event is: How has the “who” come to be doing the “what?” And what exactly does the “what” involve?

My observations and concerns are also not the response of a specialist on Ukrainian or Russian politics—I read neither language. Though area specialists are not always very good guides to anything—how many Sovietologists foresaw the end of the USSR? What I think is also not from my own first-hand experience on the ground, but it comes from open sources, some of which are provided by first-hand witnesses to the event taking place—even though it is ever more difficult to dig up information, as the internet has become increasingly algorithmically colonized by those who think they should dictate what is genuine information and what is misinformation—as if they would know.

Not only do I have no stake in thinking what I think, but I would really like to be convinced that I am not seeing clearly, that I am missing some essential evidence that would make me change my mind—as opposed to seeing that what people are presenting as evidence/facts are an admixture of dubious psycho-politics, and the ham-fisted application by analogy of historical facts to contemporary contingencies which require consideration of other historical and geopolitical facts rather than reminisces about the Russian empire and the “Russian soul,” and appeals to abstract moral and political ideals that have nothing to do with these or any other circumstances or characters.

I am well aware that many will just think that I and others who see things like me are moral pariahs or conspiracy theorists, and stooges of the evil Vladimir Putin—but the idea that someone who is trying to understand something and who disagrees with a particular diagnosis is a mere puppet of someone else (in this case Putin), and that he is spreading misinformation, and should be censored or denounced, is a symptom of what we have lost in the West—our minds along with our souls. It is much more comfortable to think that this issue is a clear-cut case of good and evil, and we all need to sing along with the rousing, feel-good moral crescendos of denunciation that are taking place wherever friends meet for a meal or drink.

Let me also say that what I present below is indicative not only of a disagreement I have with political “friends,” but also with people whose views I generally consider utterly stupid and contemptible and who are also all yelling to the rooftops that Putin is evil, and Zelensky a hero or saint.

Such people include the US triumvirate (Biden, Harris, Pelosi) who are the “leaders” of the “free world;” and the owners of the media/tech universe; and the ant-like army of mindless academicians and journalists who constitute the Greek chorus to those in power.

It is certainly possible to agree with scoundrels and imbeciles because they may be correct on a particular issue; but in the tumult of our times. it is noteworthy that almost every issue of importance is a matter of life and death, and ends up being one more reason to sort out those who are “enemies” of humankind from the self-proclaimed good, the true and the beautiful. I guess that I must be an enemy of humankind (on multiple fronts) because I hesitate to believe any of the things that have enabled the technocratic global elite. And it is fairly obvious that no matter what the crisis, it is pretty well the same bevy of benignly-beaming countenances who all know how to set us right: ranging from the benign philanthropic crew patenting vaccines like Bill Gates, or hedge fund meddlers in the political fate of nations like George Soros, or the sweat-shirted “geniacs” (I know I made that word up but it fits) at the helm of the platforms of global communication and censorship, those royal founts-of-wisdom and virtue, Charlie, Harry and Meghan, and the rest of the good, true and beautiful crew of pied pipers, court jesters, and acrobats, to the glum-drum-hum-drum-dumb-dumb ring-a-ding-zing-a-ling fun-loving types (imagine a group so interesting and hip that Klauss Schwab is their role model, and whose best bet for getting laid is attending a Davos meeting ). This last lot may seem to be relatively innocuous in the greater scheme of things, with their grey suits and with their blurred pasty faces, and clear blue-sky minds. But they are responsible for enough hot air to make us wonder if there really is another thirty years before we all burn to death, not to mention their devastating destruction of the world’s forests so they can print up their detailed plans. You got to hand it to them, though, they have come up with perfect their plan of ridding the planet of six billion people—they are going to bore everyone to death. I confess the above lot are the real reason I can’t get into Darwin’s theory of evolution.

As much as the whole gang in a sane world would be players in some Aristophanean farce, we are living in a Western cold civil war and issues that people generally treat as separate are not separate at all. For while the issues that cause division vary from climate to biology to virology, the sociology of race, ethnicity, to political theology and to domestic politics and geopolitics—the pitch and consequence is the same: families and friends, classes and nations turn against each other with ferocity; and the West is in a phase of ideological divisiveness, reminiscent of the political chaos in the post-First World War period. Putin cannot be blamed for any of this. In this civil war, the technocratic lords and their minions are winning in the West (I am sure though that their victory though will be pyrrhic). There are plenty of indications that the “glorious future” (of Western developed societies) will be one of total surveillance. All matters, from climate to environmental issues, to everything social, political, and economic will be in the hands and minds of specialists.

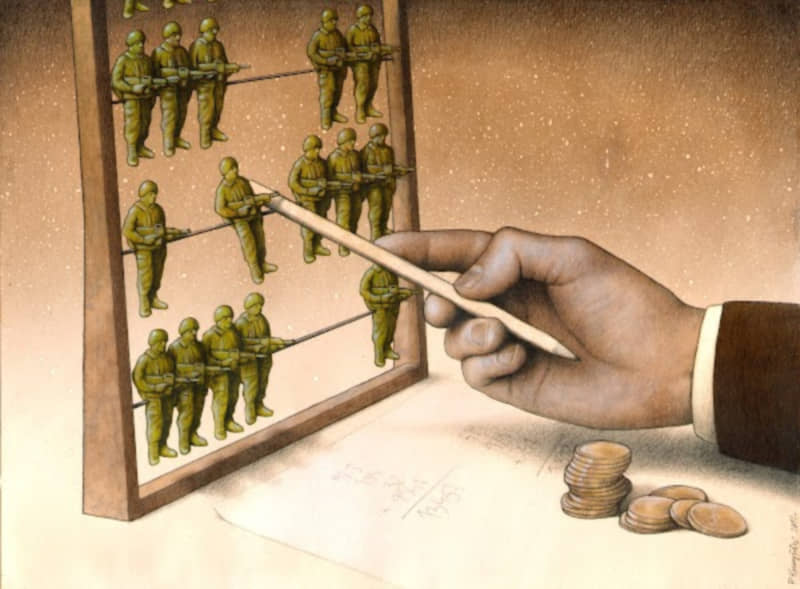

Thinkers of the left (Marcuse in One Dimensional Man) and the right (Heidegger in too many places to mention) envisaged and warned against this almost a century ago. Now one does not need to be a philosopher to make sense of the future, as it takes shape before our eyes, and we witness the transformation of politics into the mere administration of things, including humanity, as Saint-Simon initially formulated it. Food, water and air—all of life—become the “things” to be treated as part of one great calculable planning and trading system by the global oligarchs, political elite and technocrats working on behalf of their version of the good of human kind.

These considerations are neither fanciful, nor off-point. On the contrary, the idea that what is happening in Ukraine can even be remotely considered apart from what else is happening in the Western world strikes me as mad—or, in less polemic terms, methodologically deficient.

2. The Bigger Picture, Or The Great Contestation Of Our Time

The political contestation today that matters in the Western world, and thereby impacts upon the entire planet—and the only one that is really about making the future—is between those who are with a program of global leadership and compliance to the narratives of rights, sustainability, censorship, population control, and the complete technocratization of life, and those who oppose it. The lines of division are not lines that most people are even conscious of (which is typical of people in a phase of an event whose meaning is yet to become known even to the inside players—i.e., the makers of it). But in our age of crisis building upon crisis, the lines always come down to more or less the same people, providing the same methods, for the same kinds of solutions—and all based in moral principles that are ostensibly and fortuitously congruent with “the science,” and which will supposedly lead to a more equal and emancipate world (even though they actually lead to a world of greater conformity and compliance, greater censorship and control and an unprecedented scale of inequality). On this last point, consider how Western COVID policies have impacted on the economies of impoverished countries.

The Ukraine war is one more component of an assemblage of a technocratic globalist world outlook that has multiple open organs of articulation and instantiation. This outlook is widely publicized and broadly crafted. It is not a conspiracy, if one means that there is a plan that is hatched secretly and well executed. The plan—and the vocabulary in which it is formulated—is publicly aired in multiple forums from the UN to the World Economic Forum, from corporate CEOs to NGOs, from newspapers and television stations, and in university and primary school class-rooms.

If, however, one means that a group of players seeks to impose their will upon others to control the direction of resources and the organization and administration of life is a conspiracy—stated thus, then all politics is a conspiracy. Those who believe that “the science,” and hence a technocratic elite, are both necessary to solve the problems of the species and the planet then have to accept that the consequences of implementation are and will be extremely violent. It is very understandable why people think that population control, green energy, universal income etc. are very good outcomes, just as it is very understandable why peasants and workers in Russia and China thought that the solution of communism would be a very good thing. The problem with their position is not only what the world will be like if it arrives to where it is being led (see above), but the horrific costs involved in getting from this world to that future “world.” Those who are challenging this globalist vision believe that this arrival can only be achieved by a level of destruction, and domination that will make the totalitarianism of the twentieth century seem but a prelude to a greater horror.

The “to come” is the messianic formulation that a number of philosophers have used to invoke this future, which will ostensibly emancipate every oppressed group. It is just a fancy name for what Marxists-Leninist used to call “the glorious future” and the “New Man.” Its greatest obstacle is not (as endlessly repeated) the privilege and prejudices of dominators who ideologically indoctrinate the dominated—but traditions which give most people a thicker identity than the thinner ones of race, ethnicity (the very issue that has been the tinderbox in Ukraine), gender, sexuality—all distorted and self-serving ideas of intellectuals who advocate the globalist “view” of emancipation and personhood. The victims of these ideas are primarily the working classes.

Amongst the intelligentsia, it is a tiny and insignificant group of outcasts who are coming to see that any allegiances to the old alliances of left and right (liberal-conservative) have not the slightest relevance at all—because states, corporations and NGOs are equally culpable, being fully integrated into the program, which is (to use a term of that Parisian enthusiast of “nomad thinking,” Gilles Deleuze) rhizomic in its “logic” and evolution, rather than arboreal. This program is a contagion in which the makers of “the future” act in concert, without even realizing what it is that they are making or what the program even is. This too is simply the way events generally transpire, and how we all live, i.e., mostly unaware of what we are doing whilst we do it. It is global in the variety of interests, ideological preferences and types of people that are drawn into its epicentre.

Those who are being drawn in, come from every corner of the globe, and one should not underestimate the attractive “goods” that are promised—prosperity, which given the technological potential unlocked by the fusion of global forces, resources and techniques, enable the chosen ones to live as gods (no wonder the dream is to find technologies to defeat not only sickness but death itself), and pleasure, including the most intense sexual pleasures and array of pleasurable possibilities (the most widely cited philosopher of our time, Michel Foucault, was both prophet and avatar of this new “higher” type).

In most traditional societies those who seek to live their lives pursuing such pleasures have been either outlawed outright, though mostly left to seek their pleasures in hidden, draped and private spaces. But to fabricate entire life identities around a sexual act or preference, so that it becomes a means for the complete overturning of traditional institutions and the touchstone of value is insane, not least because it cannot create the same kinds of sacrificial bonds of solidarity that enable societies to persist over long period of times.

Lest anyone think I am overstating the significance of sexual identity politics, consider the public head of MI6, who came out saying at the very beginning of the Ukraine war that the real difference between Russia and the West is to be seen in how they respectively respond to LGBTQ rights.

Like pretty well every political leader in the non-Western world, not to mention the Islamic world (is it Islamophobic to mention that rainbow flags do not fly atop government buildings in Islamic countries?), Putin does not want to allow sexual identity/diversity politics to flourish in Russia; and it is one reason he is hated so much by liberals in the Western world.

I am reminded of a book I once reviewed, God in the Tumult of the Global Square, where the authors are completely flummoxed by the fact that the Russian Orthodox contingent were not on board with the other delegates at an interfaith conference that denounced critics of gay clerics—but the fact was that the Russians simply valued the importance of traditional sexual values in social formation more than individual sexual orientation, rights and choices. To think that Putin cares about private homosexual acts, because he is a nasty/pasty homophobe and who encourages the persecution of gay people, is to either be willfully misleading or to fail to see the very different point that Putin has made very clear in a number of speeches: Western sexual (and all styles of identity) politics is destructive to the traditions of Church and family; and after some seventy years of communist social destruction and another ten or so years of mayhem, Putin—and his support base—will do all in their power to resist what they see as a Western trojan horse.

With respect to the role of sexual identity politics in the dismantling and reconstruction of social institutions—and hence what the West now stands for—it is significant that the argument in favour of decriminalisation of homosexuality was based upon the sanctity of privacy. Had the matter of sexual preference and pleasure been solely a matter of private concern, it would not have posed any threat to the role of the family as such.

However, to put the pursuit and open celebration of sexual desire at the centre of our drives and needs, as Freud and the generation that came of age in the 1960s did, and now our pedagogues do, is to place appetite against traditions—all traditions—and thereby create the clearing in which we live today; and the consequences of which are also relevant to this war.

For this combination is the great attractor-force of the West today; and it is particularly attractive to the young, wealthy and vital; and it is as just as attractive to the more well-heeled Chinese, as it is to Russians, as it is to Ukrainians, as it is to the majority of middle class youth with prospects and spending power in Western lands, as it is, indeed, to those Polish students and philosophy professors who denounced Ryszard Legutko for having the temerity to see through the destructive nature of implanting a surveillance unit (of the sort that pretty well all Western universities now have) at his university to ensure that “diversity” (of sexual styles of pleasure and identities formed around those pleasures) will be protected.

That its attractiveness—and more generally the attractiveness of a life dedicated to slaking one’s desires and searching for comfort—is a mere veneer and false promise of emancipation is all too evident in the widespread despondency and social decay in the richest society the world has ever seen—drug dependency, broken marriages, abandoned or single mothers struggling to raise their children, abandoned and run away children, race conflicts, suicide rates and the widespread use of opiates to transport their users out of the pain and despair of everyday life. This is the end of the line of what the more philosophical of readers might recall was Descartes’ great vision of us becoming lords and masters of nature, viz. an eternal, comfortable life (achievable through advances in medicine).

Given this reality, is it also any wonder that given what they know through their own empty experiences of hooks-ups without love and serial monogamy, the youth and their teachers, who have been caught up in this pursuit of the pleasure-principle and its equation with life’s very meaning, as well as the most important feature of all in one’s identity, there is a search for a spiritual purpose that might redeem this morass of sadness, and despair that dwells within the surface phantasmagoria of opulence, infantilism, and eroticism.

That search, though, is undertaken by souls already brainwashed and broken and all they can do is plea for more of the same cause—they want more equity, more social justice so all on the planet may share their opulence and self-indulgence, and emptiness. These empty zombified people find their greatest spiritual core in demanding ever more service to the idols that have malformed them. Their prayers and rituals, their band of solidarity, their most genuinely joyful act is the moral outrage that they express at anyone who deviates from thinking and talking about the world that would lead others away from their gods. Their gods are (as Kant would say of the God that reason itself conjures) the “mere ideas” of their own “moral freedom,” which is their power to form absolutes that all must obey because—so they truly believe—all (except the ideologically deformed) want what they want: they call this “social justice.”

It is not only to do with sexual pleasure, but also with the divvying-up of material resources and ensuring no identity group is more privileged than another. The people who love this way have no idea what they are really doing. They are slaves of the gods of sexual indulgence, “social justice,” intersectionality, etc. and imagine they are the elite/priests selecting who will be fit to be on board the ark of the future.

What we are living through is the apogee of modern ambition and technology. Its roots combine the enlightened and romantic thinkers of the modern age. This apogee involves tearing out all other forms of sociality and encountering. But its adherents believe that they are involved in redeeming the best of traditions and people that have been silenced by history (cf. Walter Benjamin on the redemption of the oppressed). This is all advanced through an appeal to rights, anti-domination/ emancipation, equity—and an inability to consciously understand the sacrificial requirements of any kind of society; though they do unconsciously understand that they must sacrifice others (largely those who do not agree with them about their socio-political objectives or processes) to realize their dream.

That premodern societies were generally sacrificial orders is something they simply know nothing of—their moral fantasies require they speak of tribal societies as egalitarian and democratic. The Australian author and faux aboriginal man Bruce Pascoe has written a book that has received many prestigious awards and is taught in schools around the country and which claims that Australian aborigines were agrarian, settled people who lived in large towns, in a country that was the first and largest democracy. He is also a professor at Australia’s most prestigious university—the University of Melbourne. It is not the fact that he ignores the hardships of tribal life, the wars and feuds between tribes, the severity of punishments for acts of transgression, and the existential precariousness which was so great that there were numerous reports by nineteenth century authors of cannibalism; but that he depicts that world as a kind of model of what the future can and should be, if we but get our story straight and find common ground.

The symptoms of the deranged thinking of Western societies are endless—and although imbecilic thinking as the order of the day is recognized by various authors who generally badge themselves as “conservatives”—what is far less common is to identify these very bad ideas with the globalist project that is enabled, in conjunction with what is basically a sexually woke diverse Walt Disney view of the world, in which the United States and its entertainment industries provide the cultural leadership that mainstream politicians, corporations, and all the other leader types disseminate.

I am surprised that so few of my friends see the connections between the attacks upon tradition and the brainlessness and heartlessness of the woke world and the globalist forces that are not incidental to the Ukraine war—and while I cannot account for what they see, or why they don’t see it, I think that as astute as many of their critical writings of the modern spiritual and political crisis are, they are duped by the phantasm of a West that is no more, if ever it was; and the adequacy of the political vocabulary and the categories of distinction it deploys to understand the current circumstance.

It is not that I support Putin as if he and the Russians are to be likened to a team I follow, but I am very sure that much of what I am seeing is seen by Putin, as it is by a philosopher, Alexander Dugin, whose thought is gaining increasing exposure as the true source of Putin’s evil thoughts—as if apart from Dugin’s Taking over the World for Dummies, Putin’s library might resemble Pelossi’s bookshelf, and he does not have enough information-flow just by observing the world he is in. Is it being a Putin lackey to suggest if there were a test in political history and geo-politics Putin might blow away any world western leader including Boris, who one would expect to fare well in the Classics bit, but not so great in the final question, “What is going on now and what are you going to do about it?”

Apart from the ridiculousness of this cartoonish division of the world into this hybrid monster (supposedly knowing about Dugin is a sign that one really understands the mechanics of evil coming out of Russia ) and the innocent rest, what I am seeing is not something I want to see—nor is it something that I think Putin and Dugin want to see. Or to say it another way—if one looks at speeches or writings by Dugin and Putin, it is clear that they see the West in its death throes—last October Putin likened the West under the dominion of identity politics to Russia under communism, and (in spite of Putin really being a commie) that was not praise.

When Putin rebukes the West for being an “Empire of Lies” (I take up the problem of widespread Western lies—and the matter of “Russian lies” is simply not relevant to the lies of the West)—I do not know how one can deny that he has seen the rottenness that has become simply part of the day-to-day reality in the West—the fabrication, denunciation and persecution now usual in the West. I do not consider someone either wrong or an enemy, if they show me a character flaw; and I cannot see how the West can begin to heal the rifts that threaten to break it other than by addressing the lies that its elite states about itself, its opponents, and the world at large.

3. International Relations 101: The Russian-Ukraine War

International conflicts are driven by all manner of reasons, from conflict over resources, to ideological or faith-driven decisions, to prestige. Often wars are the explosive resolutions of entanglements that have occurred over protracted periods of time and past decisions which cannot be unmade without tragic collisions. The history of nations and their interests are not, at least for the most part, as in one’s own life, the result of principles and wisdom, but of circumstances that involve our own and our forefathers’ oversights, missteps, sins and crimes, as well as our and their better judgments and qualities.

In spite of the Western media coverage of this war as a clear-cut case of good vs. evil, I find the position of those who depart from that narrative more compelling. There is John Mearsheimer, International Relations Professor, who, for many years, has been warning that the United States and NATO have been creating an intolerable geopolitical threat to Russia that would result in war.

There is the former UN weapons inspector Scott Ritter whose time in active service in the first Iraq war gave him important insights into the regime of Saddam Hussein and why the claims being made about Hussein’s army and the weapons of mass destruction were false.

There is Jacques Baud who has an important essay in the Postil; and Colonel Douglas McGregor, who sums up the situation in terms of whether the USA has a legitimate and genuine national interest in what is a regional conflict.

As counter positions to the mainstream, I have also found 21st Century Wire, Patrick Henningsen podcasts, UK Column, George Galloway, Lee Stranahan, the Duran, Richard Medhurst, the Grayzone to be amongst those I tune into quite regularly and find informative. Anyone familiar with these podcasts and figures will know they fall on opposing sides on some important issues about states and markets—i.e., the left and right. But, as I state above, anyone who thinks that the demarcation between left-right, liberal-conservative, is living in a “literary reality.”

The analyses the aforementioned people provide comes from people challenging the mainstream media line (oozing out of our screens, earbuds and pages) that anything that does not support the Ukrainian cause and narrative is Russian propaganda. The most basic lesson one learns in International Politics is that peoples have different stakes to protect, and live in different “worlds” and they generally wish to protect their livelihoods and ways of being in the world—that is, people have different interests; and the word interest is synonymous with the how and why of life lived within a particular place and time. That is why it is important not just to listen to what Zelensky and the Ukrainians are saying and what we believe them to be doing, but also to what Putin and the Russians are saying and doing.

Putin has said that the invasion is to de-Nazify Ukraine—i.e., destroy the ultra-ethnic nationalist elite whose insignificant electoral representation is no indication of its social and institutional influence, and end NATO expansion.

None of the criticisms I have read against these claims takes these words seriously, though plenty try and deny that there is a neo-Nazi problem; or that the US ever conceded it would stop NATO expansion (a claim Putin often makes); or that there is any reason why Russia should be fazed by NATO expansion. I cannot take these “critical” claims seriously; and in any case, the issue is not what you or I think about how Putin should react to the number of neo-Nazis in Ukraine and the power they have garnered institutionally in pressing their interests, or about NATO expansion—what matters is how Putin and the Russian government think—and it would be wise to commence with the proposition that what they think is what they say, and if there is a mismatch between their words and deeds then interpret accordingly. I don’t think there is a mismatch. What I do see is a lot of people not listening, or not taking their words seriously.

On the matter of Russian expansion, I am inclined to defer to two figures who did foresee where NATO expansion into the East would lead, as they strongly advised against ignoring Russia’s concerns about that expansion—the architect of the US Cold War policy, George Kennan and the former ambassador to Ukraine, and career ambassador, and former ambassador to the Russian Federation William Burns. A similar position has also been aired by Peter Ford, a former UK ambassador to Syria, who has first-hand experience of that ongoing debacle of supplying arms to jihadists who were supposedly our friends and who helped in the creation of ISIS.

But NATO expansion aside, the immediate occasion of the invasion was the mass positioning of Ukrainian troops and the imminent threat of even greater escalation by the Ukrainians of border disputes arising out of the Maidan. The establishment of the Donetsk People’s Republic and the Luhansk People’s Republic, like the secession of Crimea, are the direct result of attacks upon Russian-speaking Ukrainians. Though, if the Western media is to be believed, the escalation of violence against Russian-speakers, like everything else that Russians say, was mere propaganda and it was simply an open-and-shut case of invasion.

In the Donbas, a civil war has cost many thousands of lives (14000 is the common number bandied around), most of which are Russian-speakers. This too has received scant (albeit occasional) Western media attention, though Patrick Lancaster has been living there and reporting on this unknown civil war for eight years.

What people like John Mearsheimer have been seeing and saying since the Maidan is that while this was happening the expansion of NATO and its direct support for the Ukrainian military was akin to building a massive dynamite factory beside a nitroglycerine plant—very reminiscent of the events transpiring in the Balkans prior to the outbreak of the First World War. And as with anyone investigating the causes of the Great War, it is extremely unhelpful to break the conflict down into moral bites and depict the players involved in purely moral culpability-terms, in a manner that befits school children (“Please Sir, it was the Germans and the blank cheque they gave to the Austro-Hungarians that caused it” was the answer of British schoolchildren to the “test” question: Who caused the World War).

Moralistic approaches to political history and current geopolitical circumstances are the means for avoiding rather than solving complex geopolitical antagonisms. Such antagonisms are only resolved through war (yes, sadly, it is the means of last resolve) and statecraft.

Statecraft and international diplomacy require having honed one’s mind to deal with the generation and culmination and impact of specific contingencies, actors, and historical and current forces, as well as perceived national interests; and how to deal with limited available choices of action quickly. The reduction of such complexities to normative principles is a scandal that only discloses a fundamental arrogance and ignorance within the modern liberal mind, that to be sure has gone a long way in helping the US become a hegemon, but a hegemon which inevitably leaves ruin as its monument, and causes far many more deaths than it saves.

Further, far from bringing the nations together, as the creators of the League of Nations and United Nations hoped to do, it has simultaneously devalued the international currency of norms by making it seem nothing more than a smokescreen of a particular way of being and acting in the world, which is no less violent and no more benign than the ways of other nations who not only have their own problems to deal with but, when their interests come into collision with the Western democracies, face putative measures; from ruination of their economies to invasion and a scale of warfare that makes what is happening in Kiev look like a soldiers’ picnic. (Consider how many died in the first 24 hours of the invasions of Iraq with the reported death toll in Ukraine—shock and awe.)

None of the enemies of the US fail to note that the representatives of the United States, and more generally the defenders of a liberal hegemonic international order, in international forums, deploy the moral philosophy of deontology—the rectitude of principle [i.e., Human Rights] is all important—whilst blithely embracing consequentialism on every occasion when that order and national interest is threatened (provided said order can marshal enough resources to defeat the threat).

For US and NATO interventionism (as is invariably the case with any player considering the option of initiating war) is very much driven by strategic realities; whereas poor Mr. Zelensky is a genuinely tragic figure wading in waters that he was never prepared for. Caught twixt ethnic-nationalists, who think him a clown, and oligarchs, who use him as a puppet, and portrayed by the Western media as the saintly stateman of the hour (much like Time‘s list of the world’s 100 most influential people in 2019 included that other genius of statecraft, AOC). If poll reports are to be believed, he has managed to claw back popularity amongst Western Ukrainians who had initially voted in droves for him, before thinking they had one more turkey, but who seem now eager to buy the message that Ukrainian freedom is worth armed resistance against Russia.

But forgive me if I am somewhat sceptical—what I see is that a huge number of Ukrainians have the very good sense to simply want to get out of the place. And while the Ukrainian army is sizable and well-armed, there are also reports of the government distributing tens of thousands of assault rifles to civilians. This is, as the Russian media and government rightly point out, in breach of international law, requiring the clear demarcation between civilians and combatants. While the Western media has no problem finding stories about unwilling Russian troops, we are supposed to believe that Ukrainians still in Kiev, one and all, are noble, patriotic freedom fighters. Sorry, but I grew up a long time ago, and in spite of the absurd, albeit widespread depiction within anti-Russian media, of Russia as the USSR and Nazi German redux, such analogies do not hold up to even the most cursory of examinations.

There have also been stories coming out of Mariupol of Ukrainian soldiers using civilians as human shields. Like all inconvenient stories about the war they are immediately denied, without investigation by Western journalists and said to be Russian propaganda. But, I ask, why would the non-combatants want to stay in the city, and why would the battalions that Russian soldiers are intent on destroying not be prepared to save themselves at any cost? The military tactics of the Russians do indicate that the objectives of Russia are what Putin says they are—to demilitarize Ukraine and not simply erase it. Thus, it seems plausible that any captured Ukrainian soldier found to have links with the Azov battalion or any other ethnic ultra-nationalist Ukrainian group will in all likelihood be executed immediately.

Whatever we say about Zelensky, he was as incapable of building peace in Ukraine as he was in reducing corruption. In spite of all the media hoopla he receives for his courage in standing up to a tyrant, and speeches that look like they come from US hack-tv drama writers, he was no statesman. He is either truly child-like or has so little knowledge of relatively recent history that he really thought that Russia would simply standby and wait for the Minsk agreements to continually be ignored and watch as Ukrainian forces were got ready to launch a final defeat of the Russian-speaking resistance in the Donbas.

If, by the way, anyone thinks that ethnic-nationalist militias killing Russian first language speakers with impunity, and infiltrating the various institutions of Ukraine, including the military is untrue, which is now the Western media default position, you should go back and read/watch reports in the Guardian and BBC when they were not just outlets of propaganda. You might also turn to a paper, put out by the Institute for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies at George Washington University just last September, by Oleksiy Kuzmenko, “Far Right Group Made its Home in Ukraine’s Major Western Military Training Hub.” And if you do not think providing a de facto, if not de jure, front for NATO’s strategic advancement, and threatening Russia with nuclear war, is not brinkmanship, I hazard to guess what would be.

In any case, Mr. Zelensky has had the kind of lesson in geopolitics that those who had the temerity to defy the United States have often had to learn to their peril. And while the United States and other European Nations desist from direct military involvement at least for the moment—though engaging in the now widely accepted practice of asset-seizures of Russian nationals (the future consequences of this policy bode very ill indeed for the world’s economy generally, as well as a future peace, or even the West’s economic power and credibility) as well as the sackings of Russians from all manner of jobs, from teaching to the arts—Mr. Zelensky berates the West for not being brave enough to have a full scale war.

As for the innocence of Saint Zelensky, I have said he is a tragic figure. But as he calls ever more desperately to bring the entire world into war, I cannot see him as anything other than a man who has stumbled blindly into this like a drunk with a match in the aforementioned nitroglycerine factory, panicking for his own survival; or, I will grant him this, possibly a place in the pantheon of the nation’s heroes, right alongside Stepan Bandera, that anti-Soviet Nazi ally and mass-murderer of Jews, Poles, and Russians.

If Western journalists stopped for a moment and realized that Putin does not care what they think of his actions, but he understands Russia and the events and figures within Russia’s historical memory. Putin understands that when President Yushenko posthumously awarded the medal of Hero of the Ukraine in 2010 to Bandera, and when the extremely crooked and much-hated President Pyotr Poroshenko, who emerged out of the Maidan, signed a law in 2015 glorifying the neo-fascist OUN and the UPA, this was a signal of support to Bandera neo-Nazi supporters and an acknowledgment of the need for the support of this influential power block.

Gone are the days when I, at least, could trust anything I see on the BBC. And yet again this prejudice I have developed was confirmed not just to be sheer prejudice, when a friend of mine sent me today a BBC report about how insignificant the Azov battalion and other neo-Nazi groups are in Ukraine and hence Putin was—yet again—telling lies that the roving intrepid BBC journalist was exposing. The “exposure” consisted of loosely tossing around some figures and speaking with Ukrainians who said: No there was no Neo-Nazi problem, there were hardly any of them; and in any case, they were good fighters, and their ideology was personal—akin to being a Seventh Day Adventist. One person who provided important evidence to discredit mad bad Vlad was good old Honest Poroshenko himself—who merely had to roll his eyes when asked of the existence of Ukrainian neo-Nazis.

I make no secret of the fact I think Joe Biden an idiot, but he is not such an idiot that he really thinks that Americans who have just presided over a humiliating debacle in Afghanistan want to start rounding up their kids, who are busily studying sexual and racial identity inflected subjects so they can go hook up with what and who they want, in the hope they may make themselves more virtuous, if they don’t have enough people to denounce or de-platform, by finding a riot in the summer, that is, if some unfortunate black person fulfils their dreams and gets caught in the cross-fire of police panic.

Perhaps Zelensky simply does not understand the elite priorities of the US, from its president to its woke military higher ups, which is to turn the entire world into something that highly sexualised, irresponsible teens want and understand, which certainly does not include dying for anything, let alone other people’s freedom. Moreover, on the ground, none knows where Ukraine is, and Kiev is a style of chicken dinner. They don’t really want to see their little “It,” who is doing so well at college, come back home in a coffin. Heck, one even might recall one of the major reasons why Trump got elected; that is, as Joe now stumbles around airing threats of the sort that seemed to work well enough when he had deal with that bum Corn Pop—and Vlad is just another bum after all. But for all that, Joe is not so gone (yet) that he doesn’t know that taking the US into a war would not really help him get re-elected.

The heroic leader Zelensky, as he is portrayed in the West, looks like he is in an all-or-nothing situation. And the millions of dollars he has stashed away overseas, thanks to his former media mogul boss, oligarch—and all-round gangster—political backer, also the former employer of Hunter Biden, Ihor Kolomoyskyi (yes, he was the real owner of Burisma) won’t help him much. In the midst of a country mired in corruption (a little more of which anon), Zelensky, like his predecessor, has been completely played by the US and the EU for their own interests.

Unfortunately, the Ukrainians, who are caught in the midst of the horrors, are learning what I think is the kind of thing anyone learns about in IR or IP classes 101, at least those classes that (admittedly becoming rare) are not taught by some eager beaver social justice warrior reducing geopolitics to race, class and gender. (If you think I am joking, check out how big a field feminist International Relations is now.)

In a world where one would not be denounced as a traitor or apologist of evil for thinking about national interests, International Politics teachers, when trying to understand Russia’s position and role in this event, would, I think, typically (and I have a seen a number of people more or less raise this same example) ask their students to imagine that the US has returned large parts of land annexed by Texas and California in the 19th century to Mexico.

Imagine then that the predominantly English-speaking groups within those territories found themselves disputing about regional resource extraction and distribution with Spanish-speaking groups, most of whom lived on the other side of the country. Then these ethnic tensions culminated in a coup, partly enabled by Chinese meddling in internal affairs. The regions that had formerly been parts of Texas and California became embroiled in a civil war.

The Texan and Californian Mexicans were being continuously bombed by the Mexican government—they were hearing true stories of the government closing down media outlets sympathetic to their cause, and forbidding the English language being taught in Mexican schools—just as the English did with the Irish and Welsh (and has been done in Quebec).

Then China wanted to put rockets on Mexican soil, and were sending in troops on the ground to train Mexican troops; and then the Mexican President said he wanted to build up the country’s nuclear capacity as well as have a more formal security alliance with China which it was desperate to join with other allies of China.

If a student in discussing this scenario were to pipe up and say, “The US President not only should, but would accept all this, and that any President who took military action to intervene on behalf of the persecuted ethnic Anglo-Americans and push back against Chinese meddling in its sphere of influence, would be proof of him being an evil megalomaniac”—any IR teacher would be thinking, “I have completely failed this student—he (sorry, I meant it) has no clue.”

But this all is meant to sound reasonable when we just insert the words “Putin,” “Russia,” “Ukraine” and the “USA.” It reminds me of how our educated elite think it perfectly acceptable to say that “white men are exploiters, thieves, privileged, undeserving etc.,” but were the “white men” replaced with “Jews,” “women,” “blacks,” there would be mass outrage.

The thinking that ignores geopolitical “realities” (and they are realities because of forces that have accrued over a protracted period of time; they are delicately poised; and the failure of statesmen to balance them come with massive consequences)—enables mass death. And in spite of the voluntarist metaphysical tendency that has completely seized the Western mind, these realities do not wilt under the glare of a moral(izing), that is to say, hypocritical, conscience.

It seems just yesterday, when journalists could not line up quickly enough to denounce George Bush, and prior to that Ronald Regan for being warmongers. Then at least they acknowledged (or at least a substantial number did) that the “neo-con” idea of “regime change” was deranged. Though when the Obama administration weighed in with tremendous enthusiasm for the “Arab Spring,” in what was really another variant of the same fantasy—a world of liberal democracies, all singing from the “International Community” hymn book, it should have been obvious to any thoughtful people that very few Western journalists were able to think with any real clarity outside of the safe partisan parameters that they had picked up in their training and developed in conversation with others from the same background. So it was that they easily drifted into rebooting the Cold War in order to topple that other monster Trump; and now they find themselves in that battle with the monster Putin.

Irrespective of journalists intermittently opposing US interventions, at times the US has been a mere spoiler, providing arms, training etc. At other times it has been a direct intervener—and the results have always been the same—mass death and utter disaster. I think the United States not only stood for something worth defending during the Cold War, and that Reagan (ridiculed by most of the intellectual elite) and his administration were right to break away from the Washington consensus that the Cold War was permanent, and unwinnable, and that Regan had taken the world to the brink of a world war—when in fact he was canny, and had good advisers, and took action at the right time – though if any forethought were given to the immediate aftermath, nothing good came to pass.

But this is not the Cold War. Russia is not the USSR; and the America of today has no unified spiritual core, or even a unified political purpose. Thinking that joining forces against Putin will magically produce such purpose is magical thinking. Unfortunately, the amount of magical thinking that the US has produced since the end of the Cold War has been endless (not that it was not doing some before then—e.g., whoever took over in Iran had to be better than the Shah; supporting the mujahedeen in Afghanistan against the Russians would lead to something good, etc.).

In concluding this section, I should also add that I can easily imagine that if I were a Ukrainian “first language” person living in Kiev, I would have been amongst the tens or hundreds of thousands flooding the square and streets in 2014, demanding that my interests be met, and that the President sign on to the association agreement that the EU was dangling, as a way to draw the country further into its sphere of influence. I may even have become so inflamed by the event that I may have found myself joining one of the nationalist militias, with heroes who sided with the Nazis because I would have realized that just standing in the streets, singing songs and chanting does not topple governments.

I most likely would have been full of rage that the Russians, who had promised independence, were still pulling the strings of the government, and that it was impossible to trust the good will of an ethnic group who had starved millions of my countrymen to death just as I would not feel ashamed that I had ancestors who threw their lot in with Hitler, because say what you like about Hitler, he killed a lot of Russians. Being part of such a group, I may well have beat up, or if things got really out of hand, even killed Russian-speaking Ukrainians that wanted to continue to oppress me and my family by keeping us as prisoners. Now, I would desperately want the West to come and save me, and hate Putin and see him as the cause of the panic and suffering that makes me want to flee the country.

But I am not that person—and nor am I a Russian-speaking Ukrainian from the Donbas who has also seen hospitals and schools bombed, who has lost family members since the Maidan, and whose prayers of being defended have been answered with the incursion of Russian forces. The war in the Donbas, and the bombing, shelling and shooting, as Russian foces surround major cities in their goal of toppling the government, demilitarising the country and rounding up, imprisoning, and killing members of the ethnic nationalist militias are all related to the Maidan—just as the Maidan is the consequence, not just of the enormous number of spontaneous protestors, US/ EU and Western money-meddling, but of the Homodor, and that massive crime, because of the triumph of Bolshevism. All that too is an important aspect of the part played by the likes of Stepen Bandera in the holocaust. The strands of these entanglements go back a long way, and the event of this war is an outbreak of forces that have been incubating and developing through the entanglement. Saying, “Yes but Putin started it” is, quite frankly, not a serious matter for consideration.

4. “A Thug In The Kremlin?” Or, Comparative Politics 101

If International Politics/International Relations brings with it a perspective that transports us away from what we want and what principles we think should prevail, Comparative Politics also forces us to put aside moral judgments which reach for absolutes that are also “mere ideas” and ask—just or good, in comparison to what? It was Aristotle who initially developed this as a basic procedure of Political Science, when he departed from his teacher, Plato, on the question of whether identifying the good in itself was the appropriate standard for appraising the conditions and problems of states and their constitutions.

Aristotle’s morphological approach to reality in general, though a handicap for those wanting to study the mechanics of nature, has remained as central to the development of Political Science as his discovery of Logic was to that discipline and philosophy more broadly. He saw that all living bodies have their own dynamics and pathologies. He invented the idea (albeit Plato had prepared the ground) that the Political Scientist was a diagnostician whose task was, inter alia, to tap into the strengths and weaknesses of the particular state and constitution under examination (Aristotle is reported to have collected and studied almost 160 constitutions), which led him to the conclusion that potentialities for the good of the community within states very much depended upon their circumstances. This did not mean that he did not distinguish between better and worse regimes, or that he did not acknowledge the importance of justice as a communal good. But he realized that certain goods must already be in place if others are to be achieved. And that takes time.

The history of political philosophy can roughly be broken down into two schools—one consists of thinkers like Aristotle, such as Montesquieu, Burke, and in some important ways G.W.F. Hegel, and de Tocqueville, who are driven by the comparative method which takes account of historical and social conditions which dictate the choices available to statesmen and peoples. The other school takes its bearing from norms, rational principles, arguments and ideal standards, Plato is their founder; and its modern exponents include John Locke, Jean Jacques Rousseau (who in his less known and better political observations drops it), Immanuel Kant, J.G. Fichte, the neo-Hegelians and (once one unveils the fog and contradictions of historical materialism) Marxist-Leninists, John Rawls, and (also once one gets through the thicket of fog) the post-structuralists—and George Bush and the neo-cons, Barack Obama and the liberal world order more generally.

As you can see, this second group is ideologically very diverse (hence I suppose some clown in university administration can satisfy themselves that this would be a good thing—hell, there is even a black guy in the list, and plenty of feminist theorists to fill the bill). Unfortunately, their position is built upon inferences rather than detailed knowledge of circumstance, which is also why their position is a great platform for making noble-sounding speeches; but when it comes to political action is either irrelevant (the cause of very bad decisions and inevitable failure to get the outcomes that accord with the principles, which inevitably leads to charges of outright hypocrisy), or catastrophic. This latter method, if method it really be, is easy to grasp once one adopts a first principle, an unassailable idea, which, of course, can be done with greater (as in Immanuel Kant or J.G. Fichte) or lesser sophistication, like the mainstream Western journalists and commentariat reporting on this war.

In keeping with this ‘idea-ist’ (sic.) approach, most arguments and reports about the war are framed as ethico-political denunciations of Russia—and the idea that if some fact harms the war effort of our team it must be Russian propaganda—and I have no doubt that this essay will be dismissed by many who skim it as pure Russian propaganda …oh well, this is the world we now live in.

The denunciations tend to assume one or both of the following: (a) Russia is a tyranny while the West is the font of freedom; and (b) Ukraine is really like the West both culturally and politically.

I might be more tempted to go along with this if I really believed that the West still stood for freedom, or even anything more noble than the decay, infantilism, indulgence, material grasping, and spiritual emptiness that I see devouring it. (Alert—just because Putin and Xi see this does not make them wrong, nor me their lackey in saying it.) The West no longer even stands for freedom of thought, let alone freedom of expression—the only things that might eventually enable it to get to a better, even if far from perfect, place. As for Ukraine and democracy, and Russia and their lack thereof…let’s do some comparison.

First, let us briefly consider “the money”—that variable which is so widely used to identify a people’s welfare—as in GDP per capita. In Ukraine, the official GDP per capita in 2020 was $(US) 3,800 (adjusted for ppp $12, 100). In Russia, in 2020, GDP per capita had declined by some 30 percent, since its peak in 2013, but it was still over $10, 000, and rendered in ppp almost $ (US) 26,500.

Figures such as these never tell the whole story, but I think it symptomatic of a fact that I think is indisputable—since the demise of the Soviet Union there has never been a government in the Ukraine that has not been plagued by corruption, or, and this follows inexorably from the scale of the country’s corruption, that has managed to retain great popular support. Nor one that has been able to sufficiently rein in the power of the oligarchs that Ukraine could achieve even a moderate level of economic well being.

Before addressing Russia’s “authoritarian government,” I will state another fact that I think will not appeal to people whose image of Putin comes exclusively from Western main-stream media outlets. Putin has the kind of support base in the population that Western politicians only dream of, and the reason for that is not primarily because he is a thug/criminal/stand-over merchant.

The circumstances and challenges in Ukraine and Russia, in the aftermath of communism, were somewhat similar, though Ukraine was economically the poorer, with GDP per capita being $ (US) 1257 – but had halved by 2000; in 1993 Russia’s was a tad over $ (US) 3000, and had almost halved by 2000. The geographical distribution of resources in the country had created what many might consider a very undesirable state of things—the West was more dependent upon the East for its wealth, which is also why the Crimea and the Donbas were not just a matter of national pride for the various governments operating out of Kiev.

By the turn of the millennium the GDP per capita of both had roughly halved. Then, in the Putin years there came astonishing growth in Russia, around 10 percent until 2014. This was the kind of growth which is impossible to retain for protracted periods; and not only did it slow, with a combination of sanctions and a drop in oil prices, there was a steep decline. And though it has risen since 2014, it is still not back to the figures of 2010. But compared to the previous decade substantial improvements had been made in the material conditions of most Russians.

In Ukraine the take off point occurs around the same time, but the rise is far less substantial, also followed by decline and moderate rise. Also noteworthy is the telling figure that in 2021 remittances made up 12 percent of GDP in Ukraine, foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2021 was a third of that—estimates at the beginning of the war, based upon the large outflow of refugees, were that remittances would increase by 8 percent. Yes, that increase in remittances as a percentage of GDP may be laid at the door of the Russians, but the figure of 2021 is the kind of figure that one associates with a country with economic opportunities which make leaving a smart economic move.

The other important part of the story is corruption. We hear much of Putin and his Russian oligarch cronies in the West—but I am astonished how poorly informed are most people, who are otherwise well educated, about oligarchs in Ukraine and the problems of corrupt government. As with Russia, state assets were dissolved into vouchers, and the vouchers were bought at bargain basement prices, or simply stolen by those with the know-how or muscle to do so.

Katya Gorchinskaya’s six part report, “A Brief History of Corruption” identifies the major players and plays which have left Ukrainians amongst Europe’s poorest and most corrupt nations. It begins with President Kravchuk, the first to hold power in post-Soviet Ukraine, presiding over the economic privatisation and resource gobbling.

Amongst those doing the gobbling were two Ukrainian Prime Ministers, one of whom would be successfully prosecuted in the US for money-laundering, fraud and extortion; another, Yulia Tymoshenko, would become the attractive poster face—along with Victor Yushchenko—of the Orange Revolution. Tymoshenko would eventually be prosecuted for a range of crimes, from embezzlement to involvement in the murder of another oligarch, Yevhen Shcherban, with Yushchenko himself being a witness against her.

Tymoshenko was found guilty of profiting from gas contracts signed with Russia. Although she found support amongst European human rights organizations (Yuschchenko begged to differ with their defence of her). During the 1990s she and her family had made their fortunes in energy and controlled the United Energy Systems of Ukraine (UESU). It was Ukraine’s largest gas trader, “supplying gas from Russia’s Gazprom to seven of Ukraine’s large industrial and agricultural regions.”

While the initial distribution of vouchers had initially enabled the oligarchs’ rise to power, Gorchinskaya sees the biggest asset grab as the work of politicians in 1998. As she writes: “The list of parliamentarians reads like the yellow pages of Ukraine’s future oligarchy.”

Politics and corruption are common bed-fellows. I hazard the obvious conjecture: the difference between them and Russian and Western politicians, who have made spectacular amounts of money after decades of public service, is that in Ukraine and Russia there was a brief moment of a bonanza round of assets available to them that made the usual grift seem like child’s play.

The scandals surrounding every President in the Ukraine parliament are easily discovered, and I don’t need to enter into more detail. In any case the headline from a piece in the Guardian in February 2015 sums it all up: “Welcome to Ukraine, the most corrupt nation in Europe.” It showed the West what everyone who lived there knew—that in spite of the victory over the Russian stooge/crook Yanukovich, in spite of the deaths, the noble speeches, the visits of US and European dignitaries, and promises of support, in spite of the flags, songs, international media coverage Ukraine was an economic and crime ridden dump—with magnificent scenery and a capital as beautiful as any city in the world. The article also pointed out that while “officials from the general prosecutor’s office, who were interviewed by Reuters, claimed that between 2010 and 2014, officials were stealing a fifth of the country’s national output every year,” nothing had improved.

Later that same year, a writer in Forbes magazine wrote a piece “Corruption is Killing Ukraine’s Economy.” As with Poroshensko, Zelensky, like the Presidents before him, was elected on the promise of ending corruption—though he also indicated he was the man to mend fences with Russia. He didn’t, and he wasn’t.

It is not simply the corruption I wish to underscore; it is that since the dismantling of the Soviet Union Ukraine has had two “revolutions,” and achieved nothing other than an outright civil war and a war with a great power. I don’t know how anyone who is impartial and not blinded by the patriotic fog and fervour accompanying the avoidance of the basics of international diplomacy can see it otherwise. And need I say that none of these problems—with the obvious exception of the war itself—can be traced back to Putin.

Turning to Russia, everyone of a certain age will recall that between the end of the Soviet Union and the Yeltsin years, Russia and the fall-out from its empire were in free-fall. Yeltsin had gone from being a hero of the people to a corrupt drunken buffoon. Oligarchs had taken over all the most important resources; and gangsters simply took over apartments; and the streets were not safe. The poverty was widespread and wretched.

And the reality of post-Soviet Russia made the drab days of Brezhnev and Andropov look like the golden years.

While people in the West were still celebrating Gorbachev and talking about him being a great man who changed the course of history, most Russians cursed him for creating the havoc they were living through. One cannot begin to understand Putin’s popularity if one does not concede the hell of Russia in the Yeltsin years—captured in videos of the period by images of the extremes of the old and recently rendered destitute standing on the streets huddled around a fire in the snow and ice with their knickknacks and baubles and pleading eyes; or the new phenomenon of Russian prostitution for export—the international sex trade really takes off with the end of communism—and the oligarchs and mafia with their great fur-coats, cruising by in their convoys of Western cars, and armies of protection. Stalin would not have allowed this, they reasoned. And you can say what you will about him, but he not only dressed with moderation, but he never draped his great big fur coats with gold chains, while pushing aside beggars on the way to the night club to snort blow and be blown by a girl who had drifted into the city to make some money.

Western journalists seem to think that when Putin speaks of the most terrible event being the end of the Soviet Union, that he is saying he loved communism. That is nonsense. He saw a once respected leading world power, a power, that for all its shockingness did export resources and training to those who fought on its side and from whom it saw geopolitical strategic advantage—I don’t want to get all maudlin about a system and regime that was ultimately a massive mass-murdering experiment and monstrous disaster (in no small part paid for by Western capitalists, as Anthony Sutton meticulously demonstrated). But I think to see that it was not only all for nothing; that whatever slim achievements it had made (and it would have made far more had it just been left to the autocrats prior to the Bolsheviks) had vanished along with the Soviet Union. In its place was a beggarly, broken state, of utter disorder— nothing resembling the Western commercialized sheen and shine images that one might have seen on television – but then again the sprawling tents of the homeless and junkies in Portland and San Francisco today bespeak a world resembling a similar kind of corruption, and ineptitude that Yeltsin and his mates were tolerating in Russia.

It is an odd thought, I know. But maybe what Putin said was rhetorically done for political purpose. But irrespective whether he is a “murdering swine,” as old an friend, Political Science ex-colleague, and mentor has posted on Facebook, Putin understood the rage of the humiliated, of a people who had been tricked out of the relative security—with all its scarcity—that the communist state provided, and thrown out of work and onto the streets. And he could see, as could the rest of the population, that all of this chaos was facilitated by the IMF and the Harvard Russian Project crew.

Moreover, aside from ex-party officials and their friends with their on-the-ground advantage and the armed to the teeth “wise guys” snapping up for peanuts, resources (energy and media/ communications being prime targets) worth billions and conning Russians out of, when not simply stealing, the vouchers, which were supposedly designed to distribute Soviet assets to “the people”—were Western grifters (like Bill Browder discussed below). It was a free for all in free-fall.

And on top of this were the Chechnyan terrorists and their bombs, deliberately killing innocent school children as well as adults. What made matters even worse was that Chechnyan rebels had been trained and funded by the CIA. That is a fact that Western journalists no doubt would like to put down to Russian propaganda. By the way, and lest I am sounding like the kind of left-wingers I usually take issue with for their blindness to the nature of markets, I have never been anti-everything the US does to protect its interests. But the incompetence of the US as a military and strategic power has become increasingly breathtaking, and its funding of such groups has brought nothing but havoc and understandable hatred of the West.

And, then, in the midst of this, Putin, who had been working for the mayor of Saint-Petersburg, facilitating foreign investments, and suspected of masterminding a kick-back scheme worth tens of millions of dollars, receiving a PhD for a work that had, in part at least, been plagiarised, were it even written by him, looked like just another junior on the grift “yes man” political operator had been given the nod by Yeltsin and backed by the oligarch Berezovsky, who came to regret misreading Putin’s character till the end of his life. Though, almost every Western documentary or biography depict Putin with the same sneering disbelief that this little jump-start still has power and struts around the world stage killing people, while great philanthropists and lovers of liberty like Berezovsky himself or Khodorkovsky were banished so that Putin could get nearly all of the pie.

In any case, not long after the tap on the shoulder Putin took on the oligarchs. Or, more precisely, sided with one bunch of oligarchs against another. It is fanciful to think that any political leader in Russia would have been able to survive without finding factional support amongst oligarchs— men who whose control extended to “armies” to do their bidding, protect their wealth, and trade (from arms running, to sex and drug trafficking, to gas and information). I think even the moralising denouncers of Putin don’t doubt that the level of criminality and the scale of violence of Russia’s oligarchy, and that that had touched ever part of Russia’s social fibre.

Quiz question: How would you have stopped it?

The manner in which the oligarchs accumulated their wealth as well as the tactics they deployed in defending it were all carried out in a manner befitting the kinds of weapons, financial conduits and systems, goods and services demand and supplies and political racketeering that are as mod con as mod con can possibly be: international banks laundered their money; politicians did their bidding by making deals and enacting laws that benefit them; shipping, planes and transport systems moved the girls and drugs, and immigrants with enough money to pay for their forged passports and relocation. Their computers and codes, and bank accounts in far-away lands, their hotels and majestic villas, clubs and casinos, private jets and helicopters, and yachts, their weapons and preferred drugs may have spoken of the unprecedented quality of the spoils of ill-gotten gain. But the motivation and operation were not really different from ancient tribes, or ancient and modern nations or empires seizing land and resources from enemies, or lords and kings providing their protection in return for services rendered (protection included their preparedness to not simply take everything from those they might crush were their offers of protection refused, to fighting off others desirous of those lands), or the cattle barons and robber barons, or the mafia, or those like Joe Kennedy who made a fortune out of prohibition. We accept that no one running for the presidency in the United States could be successful without finding wealthy political donors—or, at least, being an extremely rich person. But as with state foundations, the older the money the more likely it was to be founded in blood.

The way politics and wealth form a bond may vary by location, but the bond is universal, and the difference between what counts as corruption tends to also be bound up with merely how things gets done, and the wealthy get to keep their wealth and pay others to help them acquire more, and enact processes that assist their political preferences and priorities. “Not that there is anything wrong with that”—but journalists in the West tend to sleep at the wheel when it comes to following up leads that might bring down those who represent their political interests. People in far-away lands whose doings may safely be reported—even if the doings, as in the case of Putin, often (albeit not always) come from sources who also have their interests, which involve being rid of Putin.

In any case, the influence of oligarchs is no less decisive in the United States than it is in Russia. Yes, there is a rule of law, but while we may find exceptions, money generally still makes the laws.

The decisive difference between the West now and the Russia in which Putin came to power and outplayed his enemies is not in the role played by those who have the greatest wealth/control of the nations resources, it is in the timing: the violence and usurpation which provided the original sources of great wealth occurred generations back (not that long really in the USA, generally longer in the UK). And then—yes, I am really happy to go left when it is true—there was the piracy, the slavery, the colonialism. And of course it is not all in the past, where modern US “interventions” fit may vary, energy (and I don’t mean solar and wind farms) is a major factor in the West’s strategic and geopolitical decisions involving the Middle East.

This is not to make the false argument that therefore private property and capital should be eliminated, or that property is theft and all wealth ill-gotten, but commercial society is a late arrival, and where and whenever it arrives its existence requires historical and social preparedness provided by power, plunder, and protection rackets. Would that it were not so. But this is the problem with those who want to denounce Putin as if he were somehow an evil anomaly amongst those who really held power – it is so, and has ever been so. The desire it not be so is behind the ridiculous romanticization of indigenous life that originally afflicted Rousseau and now the infantilized moralizing West and its children.

The people Putin went after were amongst, or would become, the richest, the most influential people on the planet—not only financially, but also in terms of the importance of the resources they controlled for shaping the world; the other two most famous examples, apart from Berezovsky, being the media magnate Vladimir Gusinsky, who would go on to pose as a kind of religious and spiritual beacon by becoming the Vice-President of the World Jewish Congress (a gesture that would give all the Russian anti-Semites evidence to sit alongside their copies of The Protocols of Elders of Zion; he had previously cofounded and become President of the Russian Jewish Congress), and the banker, energy magnate, convicted, imprisoned and then pardoned criminal, Mikhail Khodorkovsky.

Like Berzovsky, they spend much time in exile, screaming loudly about Putin’s unprecedented wickedness (comparable, so they said to… yes, of course, who else? Adolf Hitler) to a media ready to quote them on the latest body or scandal that could be attributed to Putin and his henchmen. It seemed that Putin had nothing better than do to send out armed assassins all over the globe to silence all his critics and political opponents, because he was not only completely paranoid but his whole view of the world was picked up from KAOS in Get Smart.

Khodorkovsky has been lauded as a man of great principle by standing to face trial. This did present him with the opportunity to portray himself as a political martyr, going to prison for his belief in the sanctity of human rights and the future of democracy. The West lapped it up and lauds him still. I have a bridge with a spectacular harbour view to sell you at a discount price of ten million dollars if you actually believe Khodorkovsky has turned his life around to become a human rights activist from being a gangster and in all likelihood a murderer. It would be interesting to actually do a comparative body count between them if we could locate them.