I.

The profound historical and spiritual transformations that will determine the future of humanity are so distant from our media, from our university life, and generally from all public debates in this country, that what I am about to say in this article will certainly seem stratospheric and alien to immediate reality.

The incurably ill patient who groans in pain on a hospital bed is hardly interested, at that moment, in the medical, biochemical, and pharmacological controversies that are going on in distant countries and in languages he doesn’t know, but from which may come, one day, the cure for his disease. What is most closely related to his destiny seems distant, abstract, and alien to his pain.

Those who are interested in the future of Brazil should pay attention to what I am going to tell you here; but it will be very difficult to make them see that one has something to do with the other.

I will start by analyzing the review of an author unknown in this country [Brazil] who is reviewing the book of another author equally ignored here.

The book is False Dawn: The United Religions Initiative, Globalism, and the Quest for a One-World Religion, by Lee Penn, which I have recommended many times but few have read it, because it is a long and boring tome. The reviewer is Charles Upton, author of The System of the Antichrist, which has been even less read, which I have also recommended but with less emphasis and constancy. The review was published in a more recent book by Upton, Findings: In Metaphysic, Path, and Lore, A Response to the Traditionalist/Perennialist School.

Lee Penn’s book describes and documents, with an abundance of primary sources, the formation and development of a bionic world religion, with all the characteristics of a satanic parody, under the auspices of the UN, the US government, virtually all the major Western media, and a handful of the mega-wealthy. Started in 1995 by William Swing, bishop of the Episcopal Church, under the name, United Religions Initiative [URI], although unofficially it had existed since much earlier (going back to the Lucis Trust, founded in 1922 by Alice Bailey), the enterprise, sustained by incalculably vast financial resources and backed by a whole cast of show business and political stars, has even won the informal support of Pope Francis.

With the beautiful goal of creating “a world of peace, sustained by engaged and interconnected communities committed to respect for diversity, non-violent resolution of conflicts, and social, political, economic, and environmental justice,” the movement brings together, in festive so-called “ecumenical” celebrations, Catholics, Protestants, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, Shintoists, Animists, Spiritists, Theosophists, Ba’hais, Sikhs, followers of New Age, Wicca, Satanism, Reverend Moon, Hare Krishna and any indigenous or ufological cult that presents itself, and giving to everything a sense of universal brotherhood that blurs with smiles of mutual condescension the most obvious and insurmountable incompatibilities among these various beliefs.

All religions and pseudo-religions added together, merged and mutually neutralized, are thus reduced to an auxiliary instrument of the globalist project, aimed at creating a World Government.

Roughly speaking, the ideology that sticks these heterogeneous and irreconcilable elements together is the low brow universalism of the “New Age,” which, copying badly the language of the Hindu tradition, proclaims that all religions are nothing more than local and accidental aspects assumed by a single Primordial Revelation, from which it follows that, by this or that path, everyone will reach the highest stages of human or even superhuman spiritual realization sooner or later.

This ideology had precursors in the 19th century, such as Allan Kardec, Helena Petrovna Blavatski, the famous Theosophist and—literally—pickpocket, Jules Doinel, founder of the French Gnostic Church (1890), Gerard Encausse, better known as “Papus,” Jean Bricaud, and, in general, all the components of the movement which was to be called “occultist.”

This “universalism,” which at the beginning of the 20th century sounded only like an exotic fantasy, ended up penetrating so deeply into the common sense of the multitudes that today the equivalence of all religions in dignity and value is a dogma subscribed to by all the great world media, by the parliaments, by the legislations of almost all countries, and by most of the religious authorities themselves.

Far from being a spontaneous phenomenon, this radical transformation of collective beliefs reflects the incessant work of the omnipresent agents of URI, to whose interference no socially relevant organization is immune.

It is not necessary, therefore, to emphasize the importance of this project within globalist plans, nor, of course, is it possible to deny the value of Lee Penn’s work in gathering and sorting out more than enough documentation to prove the unity of inspiration and strategy behind phenomena that to the lay observer may seem scattered and unconnected.

The reviewer, Charles Upton, praises the merits of the book and adds a clarification that, he says, he had already transmitted personally to the author, with his full agreement.

The clarification is this: the parodic “universalism” of New Age and URI should not be confused with the high-brow universalism of the so-called “traditionalist” or “perenialist” school inspired by René Guénon, Frithjof Schuon, Ananda K. Coomaraswamy and their continuators.

It’s true. They are very different. Long beforehand, the founder of the school, René Guénon, had already subjected to devastating critical analysis the entire “occult” ideology that decades later would come to form the doctrinal basis—if one can use the term—of “New Age” and URI.

A member and even bishop of the Gnostic Church in his youth, Guénon soon came out swinging and took no prisoners. Nor did he leave intact the spiritualism of Allan Kardec, the theosophy of Madame Blavatski, and a thousand and one other movements in which Guénon saw the very embodiment of what he called “pseudo-initiation” and “counter-initiation”—the former constituting the simian imitation of spirituality, the latter its satanic inversion.

In fact, the contrast between the universalism of URI and that of the Guenonian-Schuonian current goes far beyond the mere difference between low-brow and high-brow, although this difference is obvious to anyone who compares them.

On one side we see a pastiche of inconsequential syncretisms, reinforced by some sentimental or futuristic humanitarian rhetoric (sometimes “progressive,” sometimes “conservative,” to please everyone) and adorned at most, here and there, by the superficial adherence of some fashionable writer, like Aldous Huxley and Allan Watts.

On the other side, sophisticated intellectual constructions, a deep and organized understanding of the religious and esoteric symbols of all traditions, a full command of the revealed sources, and a comparative technique that approaches, in precision, almost an exact science. In addition, some of the most consistent analyses of the civilizational crisis of the West in its various expressions: cultural, social, artistic, etc.

The difference is obvious to any educated reader. In contrast with the syncretistic mix of the “New Age,” we have here a universalism, in the strong sense of the word, a comprehensive and ordering vision that not only grasps with extreme sharpness the common points between the various spiritual cosmo-visions, but gives the reason and basis for their diversity, so that to this articulation of the one and the multiple is subordinated, in fact, the entire universal history of ideas and beliefs, theories and practices. In a word: everything that the human being has done and thought in his journey on Earth. There is practically nothing, no phenomenon, no thought, no fabulous or inauspicious event, that somehow does not find some efficient and persuasive, if not irrefutably certain, “perennialist” explanation.

From the point of view of the ordinary seeker who, coming from revolutionary, modernist and atheistic circles, is alerted to the importance of “spiritual” themes and, after a temporary illusion with the “New Age,” becomes disillusioned with its superficiality and goes in search of more nourishing food, the passage to the traditionalism of Guénon and Schuon is a formidable intellectual upgrade, an unculturating impact, almost an inner transfiguration that will suddenly isolate him from the surrounding mental environment, marked at one time by the discredit of religions and the endless vulgarity of omnipresent occultism, and will leave him alone, face-to-face with his conscience. Thus is fulfilled, on the individual scale, the famous prophecy issued by an anonymous biographer of René Guénon soon after the master’s death:

“The time will come when each one, alone, deprived of all material contact that can help him in his inner resistance, will have to find in himself, and only in himself, the means to adhere firmly, through the center of his existence, to the Lord of all Truth.”

Rare, very rare are those who reach this point—most fall by the wayside—but for those who do, it is difficult to resist the impulse to make personal contact with Guenonian and Schuonian circles, in search of relief, support and guidance. It is by this process of spontaneous selection that the “intellectual elite” is formed, which, as we shall see later on, Guénon had in view in the 1924 book East and West.

For it is clear that among the various worldviews in struggle, the most comprehensive one, which absorbs and explains all the others, is at the top. It is the summit of the consciousness of an age, the nec plus ultra of intelligence and the intelligible.

What gives even more authority to the Perenialist teaching is the repeated affirmation by its expounders that it is not their invention, but the mere transfer, in current theoretical language, of immemorial revelations that go back to a single original Source, the Primordial Tradition. An affirmation identical, on the surface, to that of the “New Age” proponents, but now based on a superabundance of documental proofs, rational arguments, and an organized science of universal symbolism and comparatism, from which are born intellectually dazzling tours de force such as René Guénon’s Symbols of Sacred Science and A Treasury of Traditional Wisdom, by Whitall N. Perry, one of F. Schuon’s closest collaborators in the USA. Schuon in the USA, a monumental collection of sacred texts organized in such a way as to illustrate, beyond any reasonable doubt, the essential convergence of the doctrines and symbols of the great religious and spiritual traditions, the “Transcendent Unity of Religions,” as Schuon called it in the title of a book that none other than T. S. Eliot considered the greatest achievement of all times in the field of comparative religion.

Any resemblance to the “universalism” of URI is misleading.

In the first place, all the Perenialists, without exception, insist that the doctrines, symbols and rites of the various traditions in particular, although they always point to a supreme Reality which is the same in all cases, have their own integrity, and cannot be subject to fusion, mixture or syncretism. In other words: they cannot undergo the kind of unifying operation that precisely characterizes the “New Age.”

Secondly, not everything that presents itself under the name of religion, spirituality, esotericism or the like can enter this synthesis. On the contrary, the precise, strict and even intolerant distinction between Tradition, Pseudo-Tradition and Antitradition is common to all Perenialists. Much of the material compacted in the “New Age” falls into these last two categories; and, far from integrating the unity of the primordial source, represents the parody or negation of everything that comes from it.

Third and most important, the transcendent unity of religions is really transcendent, not immanent. The religions there are unified only by the top, the summit and the living core of their doctrinal conceptions, and not by the irreducible variety of their liturgies, their moral codes and their different “paths” of spiritual realization. And where, precisely, is this core and summit? It is in their respective metaphysical conceptions, which are in fact convergent, as the simple collection organized by Whitall Perry suffices to show beyond all possibility of controversy. In this sense, religions and spiritual traditions can be seen, without distortion, as adaptations of the same Primordial Truth to the historical, cultural, linguistic and psychological conditions of various times, places and civilizations. The various exotericisms reflect, in their differences, the unity of the same primordial esotericism. Those who have clearly grasped the unity of this esotericism have intellectually overcome the difference between religions; but since they are not made of pure intellect and still have a historical-temporal existence as flesh and blood people, they remain subordinated to their respective religious tradition, without being able to merge or mix it with any other. The classic example is the great Sufi master Muhyi-al-din Ibn’ Arabi. Explicitly stating that his heart could assume all forms—that of the Hindu Brahman, that of the Kabbalist Rabbi, that of the Christian monk, or any other—he remained, in his life as a real and concrete individual, entirely faithful to the strictest Islamic orthodoxy.

But that’s where the trouble starts.

II.

This conception demands, besides the “horizontal” differentiation between the various traditions in time and space, a “vertical” or hierarchical distinction between the “inferior” and “superior” parts of each one. The “lower,” or exoteric, parts are historically conditioned, and by them the traditions move away from each other to the point of mutual hostility and total incompatibility. The “higher,” esoteric parts, reflect the unchanging eternity of Truth, where all traditions converge and meet.

There is, in short, a popular religion, made up of rites and rules of conduct, equal for all members of the community; and an elite religion, only for “qualified” people, who behind the symbols and laws can grasp the ultimate “meaning” of revelation. By practicing the aggregation rites that integrate them into the religious tradition, and by obeying the rules, the men of the people obtain the post-mortem “salvation” of their souls. Through initiation rites, the members of the elite obtain in life, and far beyond mere “salvation,” the spiritual realization that takes them away from the simple “individual state” of existence to transfigure them into the Ultimate Reality itself, or God.

It is good not to talk too much about these things before the general public, who may be scandalized by the decipherment of a mystery that must remain opaque for their own spiritual protection. The story of the Sufi Mansur Al-Hallaj (858-922) is well known, who after reaching the ultimate “spiritual realization,” came out shouting “Ana al-Haqq!” (“I am the Truth”) and was beheaded by the exoteric authorities. Al-Haqq does not only mean “the truth” in the generic and abstract sense. It is one of the ninety-nine “Names of God” printed in the Koran, so that Al-Hallaj’s statement was literally equivalent to “I am God.” From the point of view of esoteric orthodoxy, this resulted in denying the Koranic principle of the oneness of God, and constituted a crime that was punished by death. Later Islamic jurists admitted that statements made by Sufis in a state of “mystical rapture” escaped the purview of ordinary justice and were to be accepted as undecipherable mysteries.

In the explicit, legal, and official sense, the distinction between exotericism and esotericism exists only in one tradition: Islam. It corresponds to the distinction between shari’ah and tariqat. On one side, the religious law obligatory for all; on the other, the spiritual “way,” of free choice, only for interested and gifted people. The application of this distinction to all other traditions is merely suggestive or analogical—a figure of speech, not a proper descriptive concept. With that the whole edifice of “perenialism” begins to sway a bit.

Are there, for example, exoterism and esoterism in the Hindu tradition, precisely the one whose vocabulary René Guénon uses most frequently, because he thinks that Hinduism has achieved maximum clarity in the exposition of metaphysical doctrine? Evidently not. The caste distinction is something completely different. First, because entry into the upper caste is not free choice: the subject is born shudra, vaishia, kshatryia or brâhmana and remains so forever. Second, because accidentally members of the lower castes can reach the highest levels of spiritual attainment without changing caste. Third, because there is nothing secret or discreet about the upper caste rites, or brâhmana: any Joe-Shmo can know about them; he is just not allowed to practice them.

Is there such a thing as “Christian esotericism?” Things get formidably complicated. There were and there are, here and there, esoteric organizations professing to be Christian and which, by means of special rites, different from the sacraments of the Church, transmit initiations. The Companionship, the Fedeli d’Amore, Freemasonry and the Templar Order are examples. More modernly, numerous occultists, such as Madame Blavatski, Rudolf Steiner and Georges Ivanovich Gurdjieff have presented their teachings as modalities of Christian esotericism.

But there remain a few facts that are enough to demolish these claims.

First of all, there is no trace of any Christian esoteric organization in the first ten centuries of the Church. Secondly, our Lord Jesus Christ Himself stated flatly, “I have taught nothing in secret.” Even His parables, whose meaning was not immediately evident to everyone, were spoken in public, not to a reserved circle. How is it possible then that the core of the Savior’s teaching was kept secret for ten—or twenty—centuries?

In contrast, in Islam the difference between exotericism and esotericism is clear from the very first moment. Upon seeing a group of the Prophet’s companions practicing certain strange rites, different from the five daily prayers, the faithful went to ask him what they were about. He explained that they were voluntary devotions, meritorious but not obligatory. This was the first sign of the existence of tasawwuf or “Sufism,” Islamic esotericism.

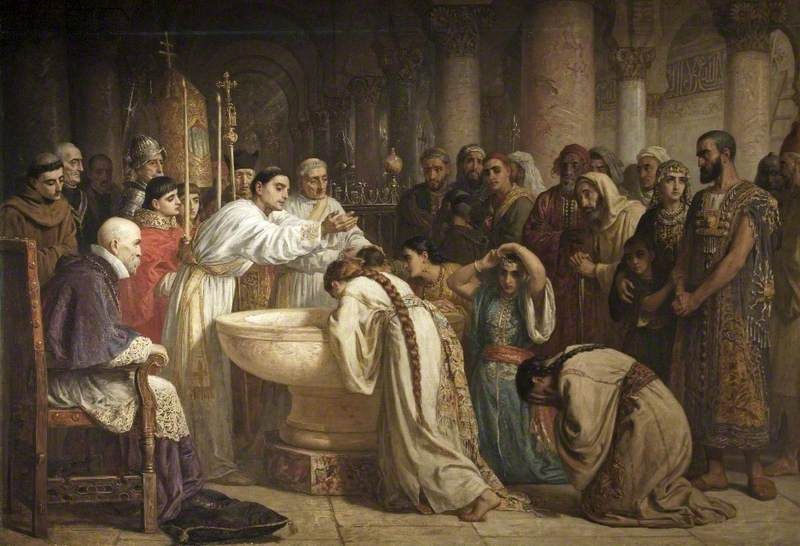

Third, and most decisive: the sacraments of the Church are not mere “rites of aggregation.” They are initiatory in their own right. They give access not only to the community of the faithful—or to their “egregora” or collective consciousness—but, Deo juvante, to the most intimate knowledge of the Ultimate Reality to which a human being can aspire. “It is no longer I who exist,” says the Apostle, “it is Christ who exists in me.”

John Paul II, in his Catechism, explicitly states that the sacraments are the steps “of Christian initiation;” and it is inconceivable that in such a formally doctrinal text he would use the term as a mere figure of speech.

Father Juan González Arintero, in two memorable books that probably constitute the summit of mystical literature in the 20th century, demonstrates with abundant arguments and examples that the way of the sacraments was opened precisely to give everyone, without exception, access to the highest levels of spiritual realization. The distinction between exoteric and esoteric is only used here as a metaphor to designate the different spiritual benefit obtained by this or that individual according to his aptitudes, his commitment and the movements of divine Grace.

All Christians who have received the sacraments are, therefore, initiates, in the strict sense that perenialism gives to this word. The difference between the various spiritual results obtained can be explained by a concept developed by René Guénon himself, that of virtual initiation. Not all initiation rites immediately produce their corresponding spiritual results. These effects may remain withheld for a long time until some external factor—or the evolution of the recipient itself—calls them into full manifestation.

To complicate things a little further, Schuon himself recognized that the Christian sacraments had initiatory scope. For one to appreciate how thorny this question is for the Perenialist school, it is enough to recall that, when Schuon’s opinion on the subject was published, Guénon reacted with indignation and fury, even breaking off relations with his disciple and continuator.

Guénon continued to maintain that the Christian sacraments were only rites of aggregation and that authentic initiations only existed in certain secret or discrete organizations, such as the Companionship or Freemasonry. To support this thesis, he invented one of the most artificial historical hypotheses anyone has ever seen—that Christianity initially emerged as an esotericism; but in view of the general decadence of Greco-Roman religion, it was forced ex post facto to popularize itself, eventually being reduced to an exotericism. There is absolutely no sign that this ever happened. Quite the contrary, Jesus spoke openly to the crowds from the very beginning of His preaching, and the sacraments have not undergone any substantial changes in form or content over the ages. Whatever his errors may have been in other areas, on this point Schuon was right.

It is also only as a figure of speech that the distinction of exoterism and esoterism—or of aggregation rites and initiation rites—can apply to Judaism, since the cabalistic mystery cultists there are none other than the very priests of the official cult.

So inappropriate is the application of this pair of concepts to extra-Islamic territory that members of the Perennialist school itself have ended up having to acknowledge the existence of “exo-esoteric” and even “exoteric” initiations alongside the properly “esoteric” ones, which is enough to show that these concepts serve little purpose.

Guénon’s lack of reasonable arguments, and his disproportionate reaction to what could have been a discussion among friends, suggest that in this episode he might have been hiding something. Unable to argue clearly, he appealed to an absurd hypothesis and tried to reduce the interlocutor to silence by a display of authority, which Schuon politely rejected.

What was the reason why Guénon would have chosen to forcibly fit all traditions into a pair of concepts that did not properly apply to any of them except Islam in particular? Why did this man, so judicious in everything else, allow himself such arbitrariness, thus putting himself in a vulnerable position that was jeopardized as soon as Schuon raised the question of sacramental initiations? He almost certainly had reasons for doing so which, at least at that time, could not be openly discussed.

But even before clarifying this point, another question needs to be raised.

III.

That materially different traditions converge toward the same set of metaphysical principles is something that can no longer be seriously doubted. The thesis of the Transcendent Unity of Religions is victorious in every respect.

There is only one detail: What exactly is metaphysics? I do not use the term as the denomination of an academic discipline, but in the very special and precise sense that it has in the works of Guénon and Schuon. What is metaphysics? It is the structure of universal reality, which descends from the infinite and eternal First Principle to its innumerable reflections in the manifested world, through a series of levels or planes of existence.

The fact that it is essentially the same in all traditions indicates that there is a normal perception of the basic structure of reality, common to all men, of any age or culture.

This perception requires a clear consciousness, or at least a presentiment of the scalarity of reality, that is, of the distinctions between different planes or levels of reality, from the sensible objects of immediate perception to the ultimate Reality, the absolute, eternal, immutable and infinite Principle, passing through a series of intermediate degrees: historical, terrestrial, cosmic, angelic, etc.

The perfect submission of human subjectivity to this structure is implied in all traditions as a conditio sine qua non of religious life and, even more so, of spiritual realization. Its denial, mutilation or alteration is the root of all the errors and follies of humanity.

This is why Schuon proposes a distinction between essential heresy and accidental heresy. The word “heresy” comes from a Greek root that has the meanings of “to choose” and “to decide.” A heresiarch is someone who, of his own volition, chooses from the total truth the parts that interest him and ignores the others.

Accidental heresy, according to Schuon, is the denial, mutilation or alteration of the canons of a particular tradition, such as monophysitism in Christianity (the theory that Jesus had only divine nature, not human nature) or associationism in Islam (associating God with other beings).

Essential heresy is the denial, mutilation or alteration of the very fabric of reality—an error, therefore, condemned not only by this or that particular tradition, but by all of them. Materialism or relativism, for example.

This is all very well, but there is a logical problem. If metaphysics is common to all traditions, how can it be the top and supreme perfection of each of them? By definition, the perfection of a species cannot be in its genus—it has to be in its specific difference. The perfection of the lion and the flea cannot reside in the simple fact that they are both animals.

It is admissible that in the individual’s initiatory climb, the arrival at the Supreme Reality, which raises him above his individual state and absorbs him into the very Being of divinity, is the culmination of his efforts. It would also correspond, according to perenialism, to the moment when the differences between spiritual traditions are definitively transcended, while continuing to apply to the empirical existence of the initiate on the earthly plane. It is Muhyi-al-din Ibn ‘Arabi being Christian, Zoroastrian or Jewish “inside,” without ceasing to be orthodoxly Muslim “outside.”

But, for this very reason, metaphysics can only be the culmination of traditions, as such, if we accept an indistinction between the order of Being and the order of knowing, which, according to Aristotle, are inverses. The top of the initiation ladder cannot be, at the same time, the culmination of religions because, being common to all of them, it is only the genus to which they belong and not the supreme perfection specific to each one.

More reasonable would be to suppose that the primordial Tradition is the common basis not only of all spiritual traditions, but of all cultures and, ultimately, of the core of sound intelligence present in all human beings. Starting from this base, or origin, the various traditions develop in different directions, each seeking to reflect more perfectly the absolute Principle and to give men the means of returning to it. In this sense, the culmination of each tradition is not the Principle itself, but the success it achieves in the operation of return. And there is no reason to suppose that, of the various species, all express equally well the perfection of the genus: fleas and lions are equally animal’ but the flea does not express the perfection of animality as well as the lion, to say nothing of the human being.

Schuon asserts that the claim of each religion to be “better” than the others is only justified by the fact that they are all “legitimate;” that is, they reflect in their own way the Primordial Tradition; but that, seen on the scale of eternity and the absolute, this claim is illusory. However, if the perfection of a species cannot reside in its genus alone, but rather in its specific difference, there is no reason to take for granted that all species equally represent the perfection of the genus. All religions refer to a Primordial Tradition. Five, but do they all represent it equally well? The question is entirely legitimate; and nowhere has the Perenialist school offered—or tried to offer—an acceptable answer to it. In fact, it has not even asked the question. Will we find even in these high places the phenomenon of the “ban on asking” that Eric Voegelin discerned in mass ideologies?

IV.

“The generation of the Traditionalist School gathered around Frithjof Schuon,” writes Charles Upton, “presented and revealed the religions in their celestial essences, sub specie æternitatis.”

If the celestial essences of the religions are substantially the same, the difference between them is purely terrestrial and contingent; the particular forms of each having nothing sacred in themselves, without the nourishment they receive from the Primordial Tradition: only the one, the Religio Perennis, is true in the strictest sense. The others are symbols or imperfect appearances of it, clothed in its various earthly incarnations.

But,” continues Upton, “these revelations are considered branches of the Primordial Tradition; but this Tradition is not presently in force as a religious system; it is not a religion that can be practiced. The only viable spiritual paths exist in the form of—or within—the present living revelations: Hinduism, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.”

But these paths lead only to “salvation” in a post-mortem life. To climb a little higher in the present life, one must, without abandoning them, join an esoteric organization and practice, besides the rites and commandments of the popular religion, some special rites and commandments of an initiatory character.

In other words, popular religion is a certificate of qualification required of the postulant at the entrance to the initiation path. For the Muslim, this is not a big problem. Although they have a separate existence, tariqas (turuq in Arabic) are generally recognized as legitimate by the official religion, so that the interested believer can move freely between the two types of practices.

For the Hindu, this is not a problem either; even though there is no proper Hindu esotericism, Hinduism accepts and absorbs all the practices of other religions, so that—apart from the political conflicts between Hindus and Muslims—nothing prevents a Hindu from joining a tariqa, Freemasonry, a Chinese Triad, or any other esoteric organization without changing his status in his society of origin.

In the case of a Catholic, however, things get complicated. According to Guénon, all Christian initiation organizations disappeared after the Middle Ages, leaving the poor faithful limited to a spiritually capricious exotericism. All that remained were the remnants of extinct organizations and… Freemasonry.

It turns out that a sentence of Pope Clement XII, in 1738, condemned to automatic excommunication any faithful Catholic who affiliated with Freemasonry (or any other secret society). The decision was reinforced by Pope Leo X in 1890 and formalized by the 1917 Code of Canon Law. The new Code of Pope John Paul II, in 1983, spoke only of “secret societies,” without mentioning Freemasonry by name, which briefly gave the impression that the excommunication had been suspended, until the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, in November of that same year, clarified that this was not the case at all; that the prohibition to join Freemasonry remained in force.

In other words, the faithful Catholic who read René Guénon and believed in him, seeing in the loss of the initiatory dimension the root of all the evils of the modern world, was pressed to the wall by the choice between giving up esotericism once and for all, being content with exotericism more and more reduced to an external moralism, or seeking Masonic initiation and being excommunicated; that is, losing the exoteric affiliation which, according to Guénon himself, was the conditio sine qua non for entering esotericism.

The conflict was not only of a legal order. Although it had remote origins in professedly Christian esoteric organizations, Freemasonry had become, in various parts of the world, an ostensibly and violently anti-Catholic force, encouraging persecutions and killings of Catholics, especially in France (during the Revolution and then again in the early 20th century); in Mexico (where this provoked the Cristero War); and in Spain, where, with the barely disguised connivance of the Masonic republican government, priests and the faithful were killed in large numbers, and many churches destroyed even before the Civil War broke out.

That is to say: the Catholic who affiliated with Freemasonry not only incurred automatic excommunication, but became a traitor to his murdered coreligionists.

Catholic Guenonians like Jean Tourniac went to great lengths to prove that Masonic doctrines were compatible with Catholicism; but, of course, this remained theoretical. Talks between Catholic and Masonic leaders in search of an agreement came to nothing. Excommunication was still in force, and the moral hazard was still very high.

Beginning in the 1960s, when these problems began to become the subject of more open discussion in the circles of those interested in traditionalism, the perenialist group began to suggest to the trapped Catholic the following possible solutions:

- Drop everything and convert to Islam.

- Seek shelter in the Russian Orthodox Church, where there is still a residue of esotericism and whose sacraments, after all, are accepted as valid by the Catholic Church.

- Join the multi-faith tariqa of Schuon, where you can practice Islamic initiation rites without formal conversion and while keeping at a prudent distance from exoteric Muslims.

The first option was certainly the most traumatic. After all, Schuon himself had written that “changing religion is not like changing country—it is like changing planet.”

The second was more comfortable, but it ran into an obstacle that I have never seen any Perenialist author even mention—the Russian Orthodox Church was infested with KGB agents, and it was almost impossible for the newcomer to find his way through that savage jungle of conspiracies and pretenses. Not coincidentally, the KGB was at that very moment organizing and training Islamic terrorist organizations for war against the Christian West.

That left the third, the easiest and most natural. Schuon’s tariqa was, in fact, full of members of Catholic origin—starting with Schuon himself and some of his closest collaborators, such as Martin Lings, Titus Burckhardt, and Rama P. Coomaraswamy, of whom the first two converted to Islam, the third remained a Catholic at least in public, while still paying the sheikh the statutory vow of total obedience required in the tariqas.

In the souls of those who remained Catholics—ex professo or in heart only—the plan that René Guénon had been outlining for the entire West since 1924 was thus being realized on a microscopic scale.

V.

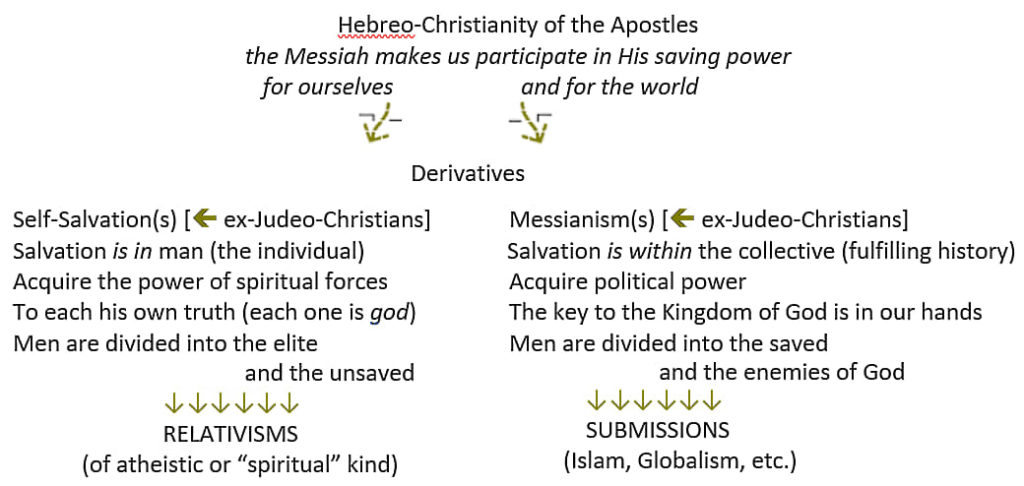

After describing with the somber colors of a genuine Apocalypse the spiritual degradation of civilization in the West, attributing it to the loss of the “true metaphysics” and the links between the Catholic Church and the Primordial Tradition (links that could only have been maintained through initiatory organizations), René Guénon foresaw three possible developments for the state of affairs in the West:

- The definitive fall into barbarism.

- The restoration of Catholic tradition, under the discreet guidance of Islamic spiritual masters.

- Total Islamization, either through infiltration and propaganda or through military occupation.

These three options were basically reduced to two: either a plunge into barbarism or submission to Islam, either discreetly or ostentatiously.

The outbreak of World War II seemed to show that the West preferred the first option’ and it is an ironic detail that important Islamic religious authorities gave the Führer their full support, especially on the question of the extermination of the Jews. Macabre coincidence or self-fulfilling prophecy? I don’t know.

After the War, the close collaboration between Islamic governments and Communist regimes in the joint anti-Western effort came to be so notorious that there is no need to dwell on this point. It is also worth remembering that today the world left, which is committed to corrupting the West “until it stinks,” as André Breton advocated, is the same one that ostensibly supports the Muslim occupation of the West through mass immigration, as well as boycotting by all means any serious effort to combat Islamic terrorism, so that there is between the two blocs a kind of Leninist agreement to “foster corruption and denounce it.” Again, the same question from the previous paragraph applies, with the same answer.

For the aspirant from a Catholic background, all the tariqa offered was the choice between becoming a Muslim or being a Catholic under Muslim guidance. The same choice that Guénon was offering to the entire Western world.

I believe that this makes Guénon’s intention to squeeze all religions, especially the Christian one, into the forced mold of an Islamic descriptive concept, the exoterism-esoterism distinction, clearer. Indeed, how can one dominate an entire civilization without first framing it within the intellectual coordinate system of the dominating civilization, where it will cease to be an autonomous totality to become part of a comprehensive map? It is also obvious that it was not enough to do this in theory; the most valuable, most intellectually active elements of the target civilization’s elite had to be won over to this new view of things. Only when the latter began to understand themselves in the dominator’s terms, instead of their own, would they be ripe to accept, without further reaction, a wider operation of cultural occupation. All the more so because the reduction of Christianity to the binomial exoterism-esoterism, accompanied by the gloomy diagnosis of the loss of the esoteric dimension, inexorably culminated in the conclusion that the “restoration of Christianity,” of its connections with the Primordial Tradition and therefore of the higher dimensions of its spirituality, could only take place under the direction of a “living esotericism,” that is, Sufism. To use Guénon’s own terms, it was necessary to submit the West to the “spiritual authority” of Islam before submitting it to its “temporal power.”

Schuon’s theory that the Christian sacraments retained their initiatory power seemed to mitigate somewhat the force of the Islamizing argument, but in fact it did not do so at all. Without the proper spiritual instruction, which only a “living esotericism” could offer him, the bearer of a “virtual initiation” remained unaware of having received it and not only remained paralyzed in the middle of the initiation climb, but risked, as a result, suffering all sorts of spiritual and psychic disturbances. Only Sufi spirituality—embodied, in this case, in the person of Schuon—could save Catholics from themselves.

The Islamization of the West—discreet or overt, peaceful or violent—is the central, and indeed the only, objective of René Guénon’s entire work. The entire work converges on this goal, not as a mere logical conclusion, but as a kind of only way out to which the reader—and, ideally, the entire West—is being led, within the walls of a labyrinthine construction, by a sense of inexorable fatality. Apart from this objective, his work is nothing more than a collection of purposeless theoretical speculations, an edifice of beautiful and unrealizable spiritual possibilities, which he always denied.

If an explicit confession were necessary to confirm this, it would suffice to recall that at the very moment when Schuon was returning from Algeria with the title of “sheikh,” vaunting his intention to “Islamize Europe,” Guénon declared that the foundation of Schuon’s tariqa in Lausanne, Switzerland, was the first and only fruit produced by his decades-long effort.

VI.

What can make this goal nebulous or even invisible to the public eye are two factors:

First: Guénon repeatedly affirmed his total contempt for any political activity, current, or ideology, assuring that his interests had nothing to do with the struggle for power, and his turn exclusively to the sphere of the spiritual and the eternal. This seems to place him, in the eyes of many, incomparably above the current dispute between Islamic countries and the West.

This way of seeing is not exactly false, it is just empty. It is obvious that Guénon is not disputing political power. He is disputing something that is infinitely above it and of which, as he himself explains, political power is only a secondary, almost negligible, reflection—he is disputing spiritual authority. He is disputing with the Catholic Church, placing himself far above it and claiming to guide it from the sublime heights of Sufi spirituality (not necessarily in person, of course).

He is very explicit on this point. The Catholic Church, at some point in its history, he says, has lost contact with the Primordial Tradition and no longer even has an understanding of the “higher parts” of metaphysics; it stops at pure ontology, or theory of Being, without penetrating the supreme mysteries of Nonbeing (Schuon prefers to say “Suprabeing”).

I have already explained on other occasions what seems to me to be the intrinsic absurdity of the doctrine of Non-Being, and I will not return to this subject here. What matters for the moment is to point out that, according to Guénon, Catholicism, from this initial mutilation, came to decline sharply until it was reduced to a mere sentimental devotion for the masses.

Since only those who can raise it from this abyss are the ones who still possess the original connection with the Primordial Tradition, it is evident that the salvation of the Church and, through her, of the entire West, can only come from outside. From where, precisely?

Not from Buddhism, since Guénon does not even consider it a fully valid tradition.

Nor from Hinduism, because it cannot be practiced outside India nor by anyone who is not of Indian nationality. All that Hinduism can provide is a deeper understanding of metaphysical doctrine—and indeed Guénon resorts abundantly to Hindu texts for this—but mere theoretical understanding, while indispensable, cannot by itself even remotely provide authentic “metaphysical realization.”

Of Judaism, even less so, for it would be inconceivable that the Church, having been born of it, would return to its mother’s womb without ipso facto annulling itself and ceasing to exist.

From Freemasonry? Impossible, not only because of the incompatibilities pointed out above and never overcome, but because, according to Guénon, Masonic initiations are only of “Small Mysteries,” secrets of the cosmos and society that do not even remotely touch the heights of the supreme metaphysical realization, the “Great Mysteries.”

From obstacle to obstacle—there is no need to examine all the alternatives—the inexorable conclusion is that the labyrinth of impossibilities has only one way out—Catholicism can only be returned to its original integrity if it consents to submit itself to the guidance of Islamic masters. Either that, or the occupation of the West by Muslims. Tertium non datur.

That, en passant, Guénon and his followers made several valuable contributions even to the understanding of Catholicism by Catholic intellectuals themselves, especially with regard to symbolism and sacred art, is something that no one in his right mind could deny.

But there again, that is nothing to be surprised about. What authority could a Sufi master claim to exercise over Catholics if, at least on some select points, he did not prove to understand their religion better than they did themselves?

Guénon’s “Catholic” articles published in Regnabit between 1925 and 1927 do not prove, or even suggest, that he accepted the independence, much less the superiority of Catholicism over Islam. They only prove that, at that period, he still believed in the possibility of directing the course of things in the Catholic Church by means of gentle persuasion and infiltration. His departure for Egypt in 1930, with the firm decision not to return and to communicate with his public henceforth only through the journal Études Traditionelles, marked the moment when he lost this hope and, integrating himself more and more into Egyptian esoteric circles (even marrying the daughter of the prestigious Sheikh Elish El-Kebir), passed the ball back to the Islamic authorities who had by far guided his actions in the European framework. How things evolved from that point to the adoption of the policy of terrorism and “occupation by immigration” (which, of course, would never have happened without the blessing of the Islamic spiritual authorities), is a story that we do not know and that can only be told, perhaps, several decades from now. What is absolutely certain is that Guénon, from the very beginning of his public activity, declared that he did not speak in his own name but strictly followed the guidance of “qualified representatives of the oriental traditions,” among whom, it is now known, was mainly Sheikh El-Kebir himself. It is utter nonsense to say that Guénon “converted to Islam” in 1930. He had been a regular member of a tariqa at least since he was twenty-one, which is enough to show that he had been long prepared for the very difficult mission he was about to undertake.

VII.

The second factor that makes it difficult to perceive Guénon’s identity as an Islamic agent is the very impact of his work on his disciples. Qualified as “the most dazzling intellectual miracle of our time,” this work sheds so many unforeseen lights on the religious phenomenon and on the spiritual decadence of the West, and so great is its contrast with all modern atheistic or Christian thought, that the temptation to regard it really as a miracle, a divine intervention in the course of history, becomes almost irresistible. Seyyed Hossein Nasr, in Knowledge and the Sacred, does not hesitate to present the entire intellectual history of the West as if it were a long, groping, half-hearted preparation for the advent of Guenonian lights. Viewed in this way, Guénon’s work seems like a supra-historical message coming from the dawn of time, from the Primordial Tradition itself, and not from a contemporary Egyptian sheikh.

The desire to erase his contemporary roots and to hover above historical contingencies is manifest in several passages of this work, and is further reinforced by several expressions of contempt for the “mere” historical perspective, according to Guénon an illusory veil of passing appearances covering up the reality of eternal things. He even criticizes the attachment of the Western mentality to “facts” as if it were a vice of thought.

Jean Robin characteristically proclaims Guenonism a providential intervention and “the last chance for the West.” It is an inalienable right of the enthusiastic disciple to celebrate the master’s work with the most emphatic qualifiers. But a qualifier means nothing when separated from the substance it qualifies. It is one thing to speak generically of a “last chance for the West”—and we all know that the West needs one. But it is quite another to make it clear that this is not just any chance, an abstract and generic “restoration of spirituality,” but rather salvation through Islamization. Jean Robin simply omits this point.

It is also very fair to privilege the eternal and immutable above the temporal and transitory. But any faithful Catholic accustomed to the sacrament of confession understands that the leap to the eternal, without passing through awareness of the factual details of earthly life, so often humiliating and depressing, is not spirituality, it is angelism. The apostle who affirms “It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me” is the same one who confesses to carrying “a thorn in the flesh” to the end of his days.

The desire to fly into the world of eternal archetypes by leaping over concrete historical reality appears not only in the hagiographic profiles of “René Guénon’s mission,” but in at least three books by important perenialist authors on Islam.

Ideals and Realities of Islam by Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Comprendre l’Islam by Schuon, and Moorish Culture in Spain by Titus Burckhardt, barely conceal their rhetorical strategy of showing Muslim life only for the eternal archetypes it symbolizes; contrasting them, explicitly or implicitly, with the gross factual miseries of the materialistic West. It is all even a little naive. Even a child realizes that it is not fair to compare the virtues of one with the defects of the other, instead of virtues with virtues and defects with defects.

All this makes it difficult, both for the newcomer reader and sometimes for the spokesmen of Perenialism themselves, to admit the obvious: the work of René Guénon can have all the providential and salvific character one wants, on the condition that one clearly admits the obvious—that, in the end, it has never offered any other way of salvation for the West except Islamization.

It is also true that any intelligent Christian, Catholic or otherwise, can benefit from the teachings of René Guénon without adhering to the Guénonian project. But how can one refuse adherence without knowing or wanting to know that the project exists? Every useful idiot is an idiot and useful to the same extent that he denies the existence of the one who uses it.

Many Christians, Catholic or not, have been so outraged by the teachings of René Guénon that they have made several attempts to refute and even deride him. These attempts only proved the intellectual superiority of the opponent and fell into ridicule or oblivion.

In this respect, Guénon’s disciples were not entirely wrong in considering him unsurpassable (the “infallible compass,” Michel Valsân said). But Guénon need neither be fought nor defeated. By adopting the pseudonym “Sphinx” in his early writings, he knew that those who did not decipher his message would be swallowed up and reduced to obedience. Those who lurch between cries of revolt will not fail to render him obedience, begrudgingly or even unconsciously. Once deciphered, however, the Sphinx has no remedy but to gently release its prey, which will emerge from its clutches not only free, but strengthened.

Olavo de Carvalho (1947-2022) was a Brazilian philosopher who lived in the United States. His books cover a wide array of topics, including Aristotle, Descartes, Saint Augustine, Saint Thomas Aquinas, and Christian philosophy. For his work, he was honored with the Grand Cross of the Rio Branco Order, Brazil’s highest award, by President Jair Bolsonaro. His most recent book in English is Machiavelli or the Demonic Confusion.

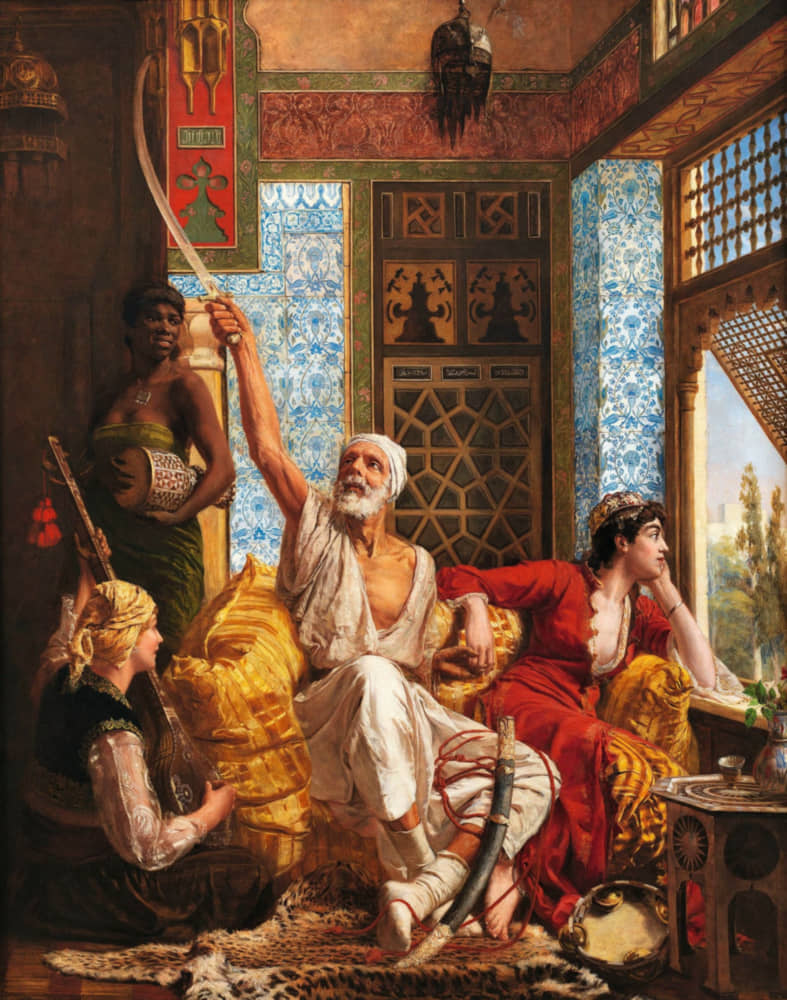

Featured image: “Prayer in Cairo,” by Jean-Leon Gerome, painted in 1865.