I intend here to return to my renovation of Platonism—and to confront some classical arguments in favor of God’s existence, then present how my claims on God and on the supraworldly realm are corroborated by cosmic evolution. I will also deal with the issue of apodicticity in mathematical knowledge—and in the knowledge of essences.

The Identity Argument

A classical argument for the existence of God goes like this. At a given moment, in a certain respect, any existing entity is necessarily what it is, rather than what it is not. It follows that any existing entity is necessarily an entity which has always existed, or an entity which was engendered by another entity; and that an entity that changes is necessarily an entity that owes its change to the action of another entity. In other words, no existing entity is an entity born out of nothing, nor an entity that changes spontaneously.

It is thought one can deduce the existence of God from this argument. Some of the entities in that world change or appear seemingly in a spontaneous manner (i.e., change or appear without finding the origin of their change in another entity existing in that world) and the universe itself has not always existed. The apparently spontaneous change and appearances, and the appearance of the universe itself, are therefore, it is said, the result of an entity eternal and external to the universe. And that entity would be God (conceived of as supramundane).

This argument is refuted as follows. The alleged fact that any entity is necessarily what it is rather than what it is not in some respect, at a given time, does not imply that any entity necessarily remains identical to itself (unless an external action to make it other than what it is at a given moment, in a given respect); nor does it imply that any entity is either uncreated or created by another entity. In other words, if one proved that our world is indeed subject to the law of identity, the fact that it is subject to the law of identity would not result in the impossibility for the entities within it—or for our world taken as a whole—to change spontaneously or to create itself spontaneously.

The aforementioned argument in favor of the existence of God—which concludes the existence of God on the grounds that entities in that world change in an apparently spontaneous mode and that new entities appear spontaneously (and that the world itself was created), and that the law of identity allegedly makes spontaneous change or creation impossible—is therefore false. The existence of God (conceived of as supramundane) would not be implied by the law of identity if it existed. The apparition of the universe from nothing would not be rendered impossible by the existence of the law of identity.

The Movement Argument

Another classic argument in favor of the existence of God, which for its part was proposed by Aristotle and taken up by Saint Thomas Aquinas, goes like this. Any existing entity that happens to be moving (in the broad sense of displacement, action, or change) necessarily finds the origin of its movement in another entity that, temporally, precedes it or is simultaneous with it. Yet an infinite regression of movers is inconceivable, whether on the worldly or supraworldly level. It follows, it is said, that the existence of a prime and supramundane mover, itself immobile, is necessarily supposed by the existence of movement in the world.

The premise of the impossibility of spontaneous movement is ambiguous from several points of view. It strictly admits two interpretations with regard to the question of the supramundane extent of said impossibility. The first interpretation is that any existing and moving entity, whether on the plane of that world or on the supramundane plane, finds the origin of its movement in another entity. The second interpretation is that in that world, and only in that world (rather than on the supramundane plane), any existing and moving entity necessarily owes its movement to another entity. To those two distinct interpretations of the premise of the impossibility of movement correspond two distinct interpretations of the argument. Either way, the argument does not hold up.

As for the first interpretation, the argument is thus refuted. The alleged facts that, on the worldly and supramundane planes, every movement (in the broad sense, therefore beyond the sole fact of moving in space) is (strictly) the fruit of another mover, and that, on the mundane and supramundane planes, every mover is necessarily either a first engine or a non-prime engine (otherwise there would be an infinite regression in the number of movers, which is allegedly inconceivable), are false. Moreover, they exclude each other, i.e., cannot coexist; and, for that, their necessary implication is self-contradictory. The force of attraction exerted in that world by quarks, stars, or apples, which falls within movement in the broad sense, is not the result of an external mover.

As for an infinite regression (in any domain), it is quite conceivable that it is possible in that world as much on the supramundane plane—and possible in that world as in other possible worlds. Besides, the allegation that movement, in that world as well as on the supramundane plane, is inconceivable in the absence of a prime mover contradicts the allegation that an external mover, in that world as much as on the supramundane plane, is necessary to generate the movement of a given entity. And that to affirm simultaneously those two premises necessarily amounts to affirming, notably, that the movement of a certain mundane or supramundane entity requires the movement consisting for a primary and supramundane mover to provoke (directly or indirectly) the movement of the above-mentioned entity, but that the movement of the first and supramundane agency will itself necessitate the movement of another agency prior to that first mover. Which is a self-contradictory, and therefore absurd, assertion.

Instead of these two premises implying that the existence of a first and supramundane agency, itself immobile, is a necessary condition for the movement of entities in that world—they imply that the movement of entities in that world has, as a necessary condition, a prime and supramundane agency, and that the latter is itself a non-immobile agency which has as a necessary condition for its movement a mover prior to that prime mover. In other words, the necessary implication of those two premises is that there is a prime and supramundane mover, itself mobile, which is both prime and non-prime, which is absurd. It is, admittedly, quite conceivable that there exists a supramundane and mobile agency which—instead of being prime—is itself moved by another supramundane and mobile agency preceding it, and that that other supramundane and mobile agency is itself moved by another supramundane and mobile agency preceding it; and so on.

But that speculation is neither the conclusion that effectively flows from the premises mentioned above (namely that any intramundane or supramundane movement is the result of an external agency, and that an infinite regression is possible neither on a worldly plane nor on a supramundane plane); nor the conclusion that the movement argument (thus interpreted) believes, wrongly, to be able to infer from said premises. The concept of an immobile mover is itself contradictory: every mover exerts a movement in so far as it exerts an agenting activity.

When it comes to concluding that there is a primary and supramundane agency, the argument from movement, if we now interpret it in these terms, is more coherent. In such a world, but not on the supramundane plane, any moving entity (in the broad sense) is necessarily moved by another entity. Yet an infinite regression of the movers is inconceivable, whether on the worldly or supraworldly plane. It follows, says the argument of movement thus interpreted, that the movement in such a world necessarily presupposes a primary and supramundane mover, itself immobile, whose agential activity is not due to another mover preceding it.

Here, the premises are now compatible, but are again wrong. Endless regression is not more inconceivable on the mundane level than on the supramundane level. Moreover, it is wrong that any moving entity in that world (as it is reasonably conjectured) finds the origin of its movement in another entity. As for the suggested inference, it is almost consistent. What the above-mentioned premises necessarily imply is in fact that movement in such a world necessarily presupposes a primary and supramundane mover itself mobile, whose agential activity finds its origin in itself. They do not imply what the argument from movement (thus interpreted) claims to be able to infer from it—namely, that they do not imply that movement in such a world necessarily presupposes a primary and supramundane driver, itself immobile. They even imply that it is wrong (and absurd) that the prime and supramundane mover be itself immobile.

As correct as the inference is that intramundane movement necessarily presupposes a primary and supramundane mover, which is at the origin of its own movement—the premise of the necessary impossibility of spontaneous movement in such a world, and the one of the inconceivability of an infinite regression of the agents on the worldly or supraworldly plane, are both false. Therefore, that alleged proof of the existence of God is not valid. Here, I will leave aside Saint Thomas Aquinas’s four other arguments for the existence of God.

The Perfection Argument

The argument of perfection, most often known as the “ontological argument,” goes like this. It is in God’s concept to be perfect. If God lacked the property of existing, something would be lacking in him; he would therefore not be perfect. It follows, it is said, that it is in the essence of God (i.e., among the constitutive properties of God) to exist. That classic argument, which dates back at least to Anselm of Canterbury, was the subject of a refutation attempt by Immanuel Kant. For my part, I claim that the Kantian critique is not more valid than is the argument from perfection itself.

The Kantian criticism goes like this. The term “is” is not a “real predicate,” i.e., a logical predicate corresponding to an alleged attribute of the object contained in the concept of the logical subject. In Kant’s terms, it is not “a concept of something which can be added to the concept of a thing.” The term “is” is either “the copula of a judgment,” i.e., a word which establishes a link between the logical subject and the logical predicate, without itself being a logical predicate; or a logical predicate which poses the object of the concept of the logical subject without itself, being a real predicate. In other words, the fact that an existing entity exists is not an attribute of said entity; and the fact that the logical predicate “exists” to be used does not add anything to the concept of the logical subject, nor does it make explicit what the concept of the logical subject contains.

The concept of perfection is certainly contained in the concept of God; but the judgment “God is” is a synthetic judgment (in the Kantian sense, i.e., in the sense of a judgment which associates with the logical subject a logical predicate, not included in the concept of said subject), which does not associate a “real predicate” to the concept of God.

Therefore, if God existed, it would not add any attribute to God that was not already formulated in his concept. Just as “a hundred real thalers contain nothing more than a hundred possible thalers,” the perfection of God, if he existed, would contain nothing more than the perfection constitutive of God according to his concept. In other words, the fact for God to exist (instead of being only possible through the concept of God) would not increase the perfection of God; but would only make it happen with all the properties which are attributed to him according to his concept, without adding or subtracting anything from his properties.

In Kant’s words, “even if I were to think in a thing, all of reality, except one; that one missing reality would not be supplied by my saying that so defective a thing exists, but it would exist with the same defect with which I thought it; or what exists would be different from what I thought. If, then, I try to conceive a being, as the highest reality (without any defect), the question still remains, whether it exists or not.” Therefore, it is impossible to infer the existence of God from the concept of perfection, included in the concept of God, just as it is impossible to infer the existence of one hundred real thalers from the concept of one hundred thalers. “Whatever, therefore, our concept of an object may contain, we must always step outside it, in order to attribute to it existence.”

Kant’s critique of the ontological argument (as Kant calls it) comes to a correct conclusion, but infers it (correctly) from a false premise. It is quite true that the existence of God would not make him more perfect than he already is according to his concept; and that the fact the concept of perfection is included in the concept of God does not render his existence necessary. Nonetheless, it remains false that existence is not a property of existing entities; and that the logical predicates “is” or “are” are not “real predicates.” Existence and the mode of existence are genuinely properties of existing entities: just as the fact of not existing and the mode of non-existence are genuinely properties of non-existent entities.

To say that Donald Duck is a fictional character genuinely consists of attributing “a real predicate” (namely “fictional character”) to the logical subject, “Donald Duck.” In other words, it genuinely consists of attributing to the logical subject, “Donald Duck,” the “real predicate” of inexistence; and, more precisely, the “real predicate” of the mode of non-existence consisting of being a fictional character (rather than a real person).

To say of a human who really existed that he was born in this or that year and died in this or that year genuinely consists of attributing to the logical subject the “real predicate” of a certain mode of existence (namely, the fact of coming into existence through birth and of existing for the duration of a human lifetime); and the “real predicate” of a certain mode of non-existence (namely the fact of having ceased to exist after death).

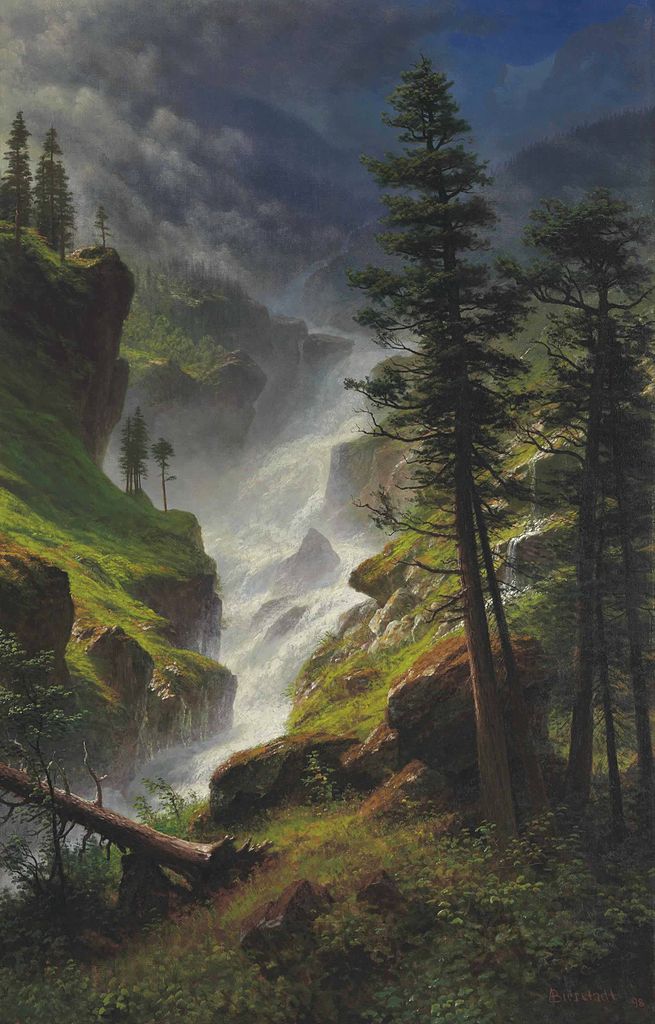

The flaw in the perfection argument is the following one. An existing entity that would be perfect in every way would not need to exist to be perfect. In other words, the perfection constitutive of a perfect existing entity would not render its existence necessary: the attribute of existence existence and the attribute of perfection would be in said entity independent of each other. Therefore, the fact that perfection is included in the concept of God does not imply that the existence of God is necessary. Just as Botticelli’s Venus does not need to exist to be perfectly beautiful, so God does not need to exist to be perfect. The existence of Botticelli’s Venus would not render her more beautiful than she already is according to her painting; the existence of God would not render him more perfect than he already is according to his concept.

So, what is going on with these concepts, including the attribute of existence – for example, the concept of substance, which includes the attribute of existence in an eternal and uncreated mode. In a certain existing entity, the attribute of existence is not implied by those attributes distinct from the attribute of existence. Therefore, the non-existential attributes of an entity, alleged by a certain concept, including, and thus alleging, existential attributes imply neither the allegation of the alleged existential attributes, nor the existence of the alleged existential or non-existential attributes. It follows that in a certain concept whose object corresponds to a certain existing entity, and whose object is defined by an attribute of existence, the inclusion of the attribute of existence does not render the object real; i.e., that the existence of the object is not implied by the inclusion of the attribute of existence. In other words, it follows that a certain concept will be true or false, depending on whether its object exists or not—and not depending on whether the attribute of existence is included or not. Jesus existed depending on whether he existed or not—and not whether or not the concept of Jesus says of Jesus that he was born in Bethlehem on December 25 shortly before the year one. Venus existed depending on whether or not she existed—and not on whether or not Botticelli’s painting shows the birth of Venus in a seashell. Substance exists according to whether it exists or not—and not whether or not its concept describes it as an uncreated, eternal entity.

The World As Incarnation

I intend now to return to my conception of God—and to argue in its defense. My conception of God, which I already introduced elsewhere, can be put as follows. Let us imagine that someone starts to write a book in an improvised mode. His story begins with a character rolling a six-sided dice, which lands on the face with three dots. On the one hand, the fact that the dice lands on that face is due to chance in the world of the story considered independently of the writer. On the other hand, in the world of the story, considered in relation to the writer, that fictional event is rendered necessary by the fact that the writer decides to land on the face with three dots.

Then the writer wonders what the possibilities are for the rest of the story, i.e., wonders what such a beginning for his story renders possible and impossible for the rest of the story. One possibility is that the character, having thrown the dice, finds himself in a casino; another one is that the character does not find himself in a casino, but in a bedroom with the dice on a bedside table. The number of possibilities is tremendous, but the writer cannot identify each of them. He finally decides that the character finds himself in a field of daisies and has thrown the dice on a wooden table. Then he continues to expand the created fictional universe by identifying possible implications and by actualizing some of them. The situation of God in relation to His creation is to some extent similar to the situation of that writer in relation to his story.

The notion of reality has a strong sense and a weak one. In the weak one, reality is the totality of what exists—whether supramundane or intramundane, and whether material or spiritual. I claim there are two levels of reality in the weak sense. One is like the letters written in a novel; the other is like the fictional world created by those letters. In the strong sense, reality is the material, worldly plane. For the sake of semantic clarity, the rest of the article will make use of the notion of reality only in the strong sense. I claim reality (understood in the strong sense) to be the incarnation of a supraworldly, spiritual plane that is like a book whose letters produce a fictional world.

Two things must be specified when doing that comparison. On the one hand, the letters of a novel do not incarnate themselves into the occasioned fictional world. But the supramundane plane, for its part, incarnates itself into the real world it occasions (while remaining virtual and external to the world). On the other hand, the letters in a novel are placed one after the other. But the supramundane plane is, for its part, atemporal—in the sense that its past, its present, and its future are simultaneous rather than successive. The supramundane plane is composed of an infinity of ideational entities—and endowed with a pulse to select some of those ideational entities and to turn the selected ones into material entities.

In selecting and materializing some ideational entities, the supramundane plane proceeds like the aforementioned writer. It starts with materializing some ideational entities (what occasions the apparition of the world from nothingness); then deciphers the possible implications from those very first materialized ideational entities. It selects some of those implications and actualizes them, what is tantamount to materializing some other ideational entities; then it actualizes some of the new offered possibilities, and so on. The world is the material, temporal incarnation of the virtual, atemporal pulse through which the supramundane plane sorts and actualizes its own content.

The pulse through which the supramundane plane sorts and actualizes its own content is also the pulse through which the supramundane plane is united. That virtual and atemporal supramundane plane united by its own sorting, actualizing pulse—and selectively incarnated into a material, temporal world to which it however remains external—is what I deem to be God. Like the aforementioned writer, God improvises His creation; and like the aforementioned writer, God plans and renders necessary those events in our world that happen in a random, unplanned manner.

As random and unplanned as are genetic mutations in our world considered independently of the supramundane plane, they are decided and forced in the supramundane plane and incarnated into our world. In improvising the course of unplanned, random events, God tries to generate ever-higher levels of order and complexity in the world; that is how an undirected, random cosmos is persistently, but fallibly, evolving towards order and complexity. Just like mistakes happen in some improvised fictional narratives, mistakes happen in the march of the improvised universe; it is not a perfect universe, nor a universe with a predefined arrival line. It is an irremediably imperfect universe, partly random (and irremediably random); but relentlessly, surprisingly evolving towards order and complexity, without the final stage of cosmic history being preset.

Again, the cosmos is a temporal, material improvised incarnation of an atemporal, virtual improvised pulse; a pulse whose past, present, and future stages happen simultaneously. The operation of that pulse does not exclude the operation of some intermediate demiurges between God and the humans; but every pulse in the world happens as an incarnation of a single pulse. Whether it comes from a demiurge, a human, a bacterium, or a dog—every pulse in the mundane realm comes as a temporal, material, singular illustration of the divine pulse, incarnating itself into the whole cosmos and remaining however external to the cosmos.

I will not venture to try to prove the existence of God (such as described here); but I believe I can show that my approach to God is highly corroborated (in default of being proven) by two things, at least. On the one hand, cosmic evolution, as conjectured nowadays in Western science, is an undirected, largely random process that however leads, more or less, to ever-higher levels of order and complexity. By itself, such a process is highly unlikely to result in such high levels of organization as those conjectured.

My approach to God proposes a solution to that paradox and transcends the opposition between the thesis of the “intelligent design” and those theoretical conceptions known as “Neo-Darwinism.” Cosmic evolution (including biological) is indeed undirected and largely random, as so-called Neo-Darwinists claim; but it is also the shadow, so to speak, of a directed, spiritual process. The latter is not present in the world, in which evolution is really undirected and (partly) random—unlike what the proponents of the “intelligent design” thesis believe. Instead, the divine process, which is purposeful and nonetheless fallible, is incarnated into the cosmos, which remains undirected and largely random for its part.

On the other hand, my approach to God takes into account the existence of suprasensible intuition, i.e., the experience of the supraworldly, ideational realm through unempirical perception. Suprasensible intuition is especially practiced in the knowledge area known as mathematics—as Pythagoras and Plato claim. For the sake of semantic clarity, the rest of the article will call “entities” only those distinct beings that are material and intramundane.

The distinct beings within the supraworldly, ideational realm will not be called entities. The distinct ideational beings include numbers and figures; but, also, the ideational models for the entities within the worldly realm—as much those that used to exist as those presently existing and as those existing in the future. The ideational models within the supraworldly realm also include models for those entities corresponding to possible worlds that the sorting, actualizing pulse chooses not to actualize. The issue of knowing whether some truths in that world remain true in all the possible worlds is an old one. Mathematical truths are often thought to be such truths—and, more precisely, thought to remain true in all the possible worlds through being apodictic statements. I intend now to turn to that issue.

Mathematics As Suprasensible Intuition

An allegedly apodictic statement is a statement allegedly true by its sole terms—and therefore true by right and true whatever may be. An allegedly analytical statement is a statement that, allegedly, is true or wrong depending (and depending only) on the (correct) laws of formal logic. In Kant’s approach to analyticity, an analytical statement is, more precisely, a statement in which the predicate is included in the concept of the subject. In the approach of logical empiricism, an analytical statement is, more precisely, a statement that is either tautological (i.e., true for any distribution of the truth-values in the calculation of predicates), or reducible to a tautology (i.e., a statement true for any distribution of the truth-values in the calculation of predicates). In Leibniz’s approach, an analytical statement is, more precisely, a statement whose opposite is self-contradictory.

An allegedly synthetic statement is a statement that, allegedly, is true or wrong depending (and depending only) on whether it is congruent with reality. In Kant’s approach to syntheticity, a synthetic statement is, more precisely, a statement in which the predicate is not included in the concept of the subject. In the approach of logical empiricism, a synthetic statement is, more precisely, a statement that is neither tautological nor reducible to a tautology. In Leibniz’s approach, a synthetic statement is, more precisely, a statement whose opposite is not self-contradictory.

The problem with the notion of apodicticity is dual. Firstly, the problem is to know whether an apodictic statement is possible. Secondly, it is to know whether an apodictic statement (if it is possible) is necessarily an analytical statement. Kant is commonly thought of as claiming the mathematical statements to be apodictic ones that are nonetheless synthetic in the Kantian sense, i.e., endowed with a predicate that is not included in the concept of the subject.

According to my understanding of Kant’s approach to mathematics, he really conceives of mathematical statements as synthetic statements that are not apodictic; but which can nonetheless be proven true or false independently of sensible experience. And that by reason of the fact their concepts are constructed exclusively within the “pure forms of sensible intuition” that are, according to Kant, space and time, i.e., the fact that their concepts are constructed not on the basis of sensible experience, but only within the a priori spatial, temporal framework that the human mind, according to Kant, confers onto sensible experience. What Kant has in mind when speaking of an “a priori synthetic judgment” is not an apodictic synthetic judgment, but a synthetic judgment that, while being a priori (i.e., independent of sensible intuition) and while being not apodictic, can be proven true or false when—and only when—constructed within the human mind’s “pure forms of sensible intuition.”

Kant’s thesis (that mathematical judgments exclusively deal with concepts the human mind spontaneously constructs within the spatial, temporal framework of the human mind) is notably opposed by the one—notably shared by Pythagoras and Plato—that mathematical statements are exclusively the fruit of suprasensible experience. I will leave aside the issue of knowing whether Pythagoras and Plato also think of mathematical statements as apodictic ones.

In my opinion, Kant’s thesis suffers two flaws, at least: on the one hand, a logical flaw (i.e., a flaw in terms of internal coherence); on the other hand, an analytical error, i.e., a mistaken appreciation of reality. On the one hand, it claims the (true) mathematical synthetic judgments to fall both within unapodictic statements (i.e., those statements that are not true by the sole reason of their terms) and a priori, objective knowledge (i.e., objectively true knowledge logically anterior to sensible experience); but is really unable to account for the alleged ability of the human mind to determine in an a priori mode (i.e., independently of sensible experience) whether its mathematical synthetic judgments are true or wrong.

If mathematical judgments were, indeed, both unapodictic and (exclusively) constructed within the alleged spatio-temporal framework of the human mind (as Kant claims), the fact would still remain that such origin for mathematical judgments would not allow the human mind to determine in an a priori mode whether those unapodictic judgments are true or wrong. Thus, Kant’s thesis leaves unexplained an alleged fact it proposes to explain: the alleged character of (true) mathematic judgments as a priori, unapodictic, objectively true knowledge.

On the other hand, Kant’s thesis is partly mistaken about the origin of mathematical synthetic judgments. Those are really the fruit of suprasensible perception to some extent; and the fruit of the human mind to some extent. Here I will leave aside the issue of knowing whether the mathematical statements the human mind is able to conceive (and able to conceive of as true) are necessarily an extension of statements the human mind is able to conceive of as true by the sole operation of certain admitted logical laws. Or the issue of knowing whether any true mathematical statement, i.e., any mathematical statement congruent with reality, is necessarily an extension of certain admitted logical laws congruent with what may be called the ontological structure of reality. My only points here are the two. First, the truth of a mathematical statement—such as “7 + 5 = 12”—is not apodictic. Second, our mathematical concepts and statements are to some extent the product of the suprasensible perception which Plato and Pythagoras refer to; and to some extent the product of the human mind itself.

At least in that world, perhaps also in all the possible worlds (which remains to be determined—and I will leave aside that issue here), an apodictic statement (i.e., a statement true by its sole terms—and therefore true whatever may be, and true by right) cannot exist. At least in our world, a true statement can be true only by virtue of its conformity to reality. Hence, there can be no statement true by reason of its sole terms. A certain statement that holds true, whatever may be, is true by virtue of a certain fact that remains whatever may be, i.e., a certain fact that remains in all the possible worlds; but it is not true in an apodictic mode.

The same applies to logical laws and to definitions. An objectively valuable logical law, i.e., a logical law that objectively allows for coherent lines of reasoning, is objectively valuable because it is in line with the ontological structure of (our) reality; but it is not rendered objectively valuable by its sole terms. The law of identity, the law of non-contradiction, the law of the excluded middle, the modus ponens, the modus tollens, etc., cannot be logically valuable unless the corresponding alleged ontological facts (i.e., the alleged fact that any existing entity is necessarily what it is, rather than what is not, etc.) are real. Likewise, an objectively valuable definition is necessarily a true definition, i.e., a definition that is congruent with reality; it cannot be rendered objectively valuable by its sole terms.

An allegedly analytical statement is an allegedly apodictic statement that allegedly owes its apodicticity to being true by the sole operation of some (allegedly correct) logical laws. An admitted logical law is not analytical, i.e., is not rendered true or false by its own operation; but it is true or false, depending on whether it is congruent with the ontological structure of our world. A tautological statement is a statement that certain admitted logical laws (whatever they may be) deem to be true (or deem to be false) for any distribution of truth values. A tautological statement necessarily expresses what it claims to be—a certain illustration (in our world) of the ontological structure common to all the possible worlds. For instance, “a cat is cat” expresses a certain illustration of the ontological law of identity—and implicitly claims such law to be common to the ontological structure of all the possible worlds.

A tautological statement is not analytical, i.e., is not rendered true or wrong by the sole operation of certain admitted logical laws; but it is true or false, depending on whether it is congruent with an actual illustration (in our world) of a certain ontological law of our reality—and on whether that ontological law is common to our world and to all the possible worlds. “A cat is a cat” is true depending on whether the alleged fact that a cat is a cat is an actual illustration (in our world) of an actual ontological law in our world—and on whether that ontological law is common to the ontological structure of all the possible worlds.

A definition is a statement of some alleged properties in the object of a certain concept. An admitted definition in a certain language is contentless and conventional from the angle of that language, considered independently of reality; but it is informational and speculative from the aspect of that language considered in relation to reality. An admitted definition is not analytical, i.e., is not rendered true or false by the sole operation of certain admitted logical laws; but it is true or false depending on whether it is congruent with the object of the definition. A mathematical statement is not analytical either; but it is true or false depending on whether it is in line with what may be called the mathematical field of reality.

Here I will leave aside the issue of knowing whether a mathematical statement and a definition can be reduced to a tautology; but let us admit they can be reduced to a tautology, i.e., a statement that certain admitted logical laws deem to be true for any distribution of truth values. Their reducibility would not render them analytical—since they would be reducible to a (tautological) statement that is not analytical. Saying that a statement is true for any distribution of truth values, in regards to certain admitted logical laws, is tantamount to saying that the latter is true in all the possible worlds in regards to those laws. Yet a statement is not rendered effectively true in all the possible worlds by the fact of being tautological in regards to certain admitted logical laws.

The only way for a statement to be true in all the possible worlds (i.e., true whatever may be) is to be congruent with a fact that remains in all the possible worlds. A tautological statement is not contentless (as Ludwig Wittgenstein and others claim). If it were a contentless statement, it would be neither true nor wrong; but a tautological statement is true or false depending on whether it is congruent with an actual illustration (in our world) of an ontological law common to all possible worlds.

Wittgenstein’s claim that a tautological statement exhibits (but does not tell) the ontological structure of our world (and only that of our world) is doubly wrong. Instead, a tautological statement tells (instead of showing) what it claims to be—the ontological structure common to our world and to all possible worlds. If any possible mathematical statement is reducible to a tautology, then any possible mathematical statement speaks of the ontological structure allegedly common to our world and to all possible worlds. Any possible mathematical statement is true or false, depending on whether it is congruent with an actual illustration (in our world) of an ontological law common to all the possible worlds.

Going back to Kant’s claim about the origin of mathematical judgments, I suspect that the human mind is indeed endowed with a spatio-temporal framework which it uses to structure the sensible content; and that such framework is innate or acquired through experience or culture. But the human mind is not the only originator of its mathematical statements and concepts; they are to some extent the fruit of suprasensible intuition (in people highly gifted with suprasensible perception). On the one hand, the human mind’s spatio-temporal framework hosts within it the fruit of suprasensible intuition; on the other hand, the human mind works from the fruit of suprasensible intuition and generates its own mathematical concepts and statements.

The necessarily flawed character (to a varying degree) of a suprasensible intuition is one of the reasons why our mathematical knowledge is necessarily perfectible—and why revolutions can happen in mathematics. The fact the human mind, when it does not host the necessarily flawed fruit of a suprasensible intuition, only deals with its own invented concepts and statements, is another reason for the perfectibility of our mathematical knowledge. It is true that our mathematical concepts and statements, whether they stem from suprasensible intuition or from the human hind itself, can be corroborated by reality, such as it is observed or conjectured; but our observations of reality and our conjectures about reality can only corroborate our groping mathematical knowledge. They cannot confirm it. Such affirmation deserves further clarification, which I intend to deal with elsewhere.

The Issue Of Essences And Definitions

Besides containing ideational numbers and figures, the ideational domain also contains ideational models for existing entities (as well as for those that used to exist and for those that will exist). The essence of a (material) entity is what a (material) entity is. More precisely, it is both what an entity is—and what makes said entity be what it is, rather than be what it is not.

The essence of an entity is dual: it has an ideational component on the one hand; and a material one on the other hand. The ideational essence, i.e., the ideational component of an essence, contains the sum of all the properties of the considered (material) entity. The material essence, i.e., the material component of an essence, only contains the sum of all the constitutive properties of the considered (material) entity. I intend now to deal more extensively with the subject of ideational and material essences.

A mistake by Plato was to conceive of essence as only ideational—and to conceive of ideational essence as only containing the constitutive properties. More precisely, those constitutive properties that are general in the strong sense, i.e., attached to the genre under which a considered entity falls. An ideational essence instead contains the sum of all the properties of the considered entity—and not only those properties that are both constitutive and general in the strong sense.

As for the material essence, it only contains those properties that are constitutive—but as much those constitutive properties that are general in the strong sense as the rest of those properties that are constitutive. Another mistake by Plato was to conceive of the material entity as partaking of its ideational model. Any material entity is instead the incarnation of its ideational model, which incarnates itself into the corresponding material entity while remaining ideational and external to the corresponding material entity.

The definition of a material entity can be unique to some individuals, or can be generally admitted, i.e., admitted in a certain language and common to all the people participating in that language. Any definition deals with some properties of the defined material entity; more precisely, those properties whose inclusion into the considered definition allows the latter to make the considered entity easily distinguished (and recognized) when referred to in a certain statement. The properties evoked in a certain definition do not necessarily coincide with the constitutive properties of the defined entity. But the definition of a certain entity is true or false, depending on its conformity to the properties of the entity. Here, I will leave aside the issue of defining properties rather than entities—and the issue of defining ideational models rather than material entities.

A property is what is characteristic of a certain (material) entity at a given moment of the entity’s existence. Among the properties of an entity, some are constitutive of said entity, i.e., part of what makes that entity what it is (rather than what it is not); others are accessory, i.e., external to what makes that entity what it is (rather than what it is not).

Among the constitutive properties, some are innate to an entity, i.e., are attached permanently to said entity over the course of its existence (unless its integrity is broken); others are emergent in the weak sense, i.e., become attached (whether permanently or temporarily) to said entity over the course of its existence. Among the emergent properties in the weak sense, some are constitutive; others are accessory. Among the emergent properties in the weak sense, some are emergent also in the strong sense, i.e., they introduce qualitative novelty into the world; others are emergent only in the weak sense, i.e., are properties that become attached (instead of being permanently attached to the considered entity over the course of its existence), but which are not novel qualitatively.

Among the properties of an entity, some are necessary, i.e., are forced to be attached permanently to the entity, or are forced to become attached to the entity; others are contingent, i.e., are attached permanently to the entity, or become attached, but without being forced to be attached permanently or forced to become attached. Among the necessary properties, some are constitutive, permanent properties; others are constitutive, emergent (in the weak sense) properties. Among the constitutive properties, some are general in the strong sense, i.e., are attached to the genre within which the considered entity falls; others are unique, i.e., are attached to the considered entity but are not attached to its genre.

While any constitutive, permanent property is also a necessary property, any necessary property is not a constitutive, permanent property. While any general property in the strong sense is also a constitutive, necessary property, any constitutive, necessary property is not a general property in the strong sense. Among the properties of an entity, some are fundamental; others are secondary. Among the constitutive properties of an entity (whether they are permanent or emergent in the weak sense, and whether they are general in the strong sense or unique), some are fundamental; others are secondary.

The ideational model of a certain entity contains the sum of all the properties of said entity over the course of its existence—as much those constitutive, as those accessory; as much those permanent, as those emergent in the weak sense; as much those emergent only in the weak sense, as those emergent also in the strong sense; as much those necessary, as those contingent; as much those general in the strong sense, as those unique; as much those fundamental, as those secondary. Any admitted definition in a given language is true or false depending on the quality of the reality—whether or not that definition only deals with all or part of the constitutive properties of the defined entity. Any admitted definition is both a contentless statement from the aspect of language considered independently of reality—and an informational statement from the aspect of the confrontation of language with reality.

What is more, any admitted definition is both conventional from the aspect of language considered independently of reality—and conjectural from the aspect of the confrontation of language with reality. No definition (whether it is generally admitted or not) is analytical, i.e., true or false by the sole operation of certain admitted logical laws. But any admitted definition in a given language is thought (by that language) to be synthetic, i.e., to be true by being congruent with reality. No definition (whether it is generally admitted or not) is rendered true by the fact that the involved language deems that definition to be true; but any definition is true or false depending on reality.

Any definition is likely to get updated when progress is made in the knowledge of reality—whether such progress is made through (sensible) observation, through corroborated conjecturing, or through suprasensible perception (i.e., through the suprasensible grasp of ideational models). As for those (impracticable) definitions dealing with all the properties of a certain entity—a perfectly true definition of that kind is a definition perfectly mirroring the whole ideational model of the defined entity. And as for those definitions only dealing with all or part of the constitutive properties of the defined entity—a perfectly true definition of that kind is a definition perfectly mirroring all or part of the constitutive properties formulated within the ideational model of the defined entity. The ideational entities within the ideational domain are too much complex with respect to what a human mind is really able to understand (no matter how powerful a human mind is). Hence, the suprasensible grasping of a certain ideational model by a certain human mind is necessarily imperfect. In other words, only a more or less misrepresentative portrait of a grasped ideational model can be obtained through suprasensible intuition.

Conclusion—And A Few Words On The Kabbalah

The problem of knowing whether the world emerges from God is different from the problem of knowing whether God necessarily occasions the existence of the world. Besides, the latter arises differently, depending on the answer given to the former. If God, conceived of as substance (in the sense of an uncreated, necessarily existing entity), creates the world, the question of the necessary or contingent character of the world’s causation then applies to a world distinct from God. If God, conceived of as substance (in the sense of an uncreated, necessarily existing entity), sees the world emerging from God, the question of the contingent or necessary character of the world’s causation then applies to a world that constitutes a constitutive emergent property in the strong sense, i.e., a property that, while being constitutive of God and introducing novelty, is not co-eternal with God.

For my part, I claim that the world is neither created nor emergent, but that it incarnates God (conceived of as uncreated and as necessarily existing), who nevertheless remains distinct from said world (as the Father remains distinct from the Son, who is nevertheless His incarnation). That relation of incarnation is necessarily occurring. Hence, the world is necessarily occasioned. Besides, that relation of incarnation is co-eternal with God—although the world has a temporal beginning.

The cosmos is neither an emergent property of God (as in the medieval Kabbalah), nor a product of God (as in the modern Kabbalah). The cosmos is an incarnation of God— more precisely, an incarnation of the book, that is—both in a simultaneous and improvised mode—written in God’s mind. The Kabbalah’s idea that the cosmos is created through letters is thus deepened in this way: the cosmos is created through an improvised, atemporal writing process, incarnating itself into the temporal, (partly) random cosmos.

As for the Kabbalah’s idea that man is made in the image of God and is mandated both to repair the world and to respect God’s law, is deepened in this way: the writing process incarnating itself into the world aims to accomplish ever-higher levels of order and of complexity, but is likely to commit mistakes. It is up to man to repair those mistakes to the extent possible—and to respect at the same time the cosmic order, which is part of God’s law to humans.

When some men are trying to repair the creation, they are really the incarnation of God trying to repair His own work through them. Yet some men are more linked to God than others—and therefore, more able than others to grasp the writing process through suprasensible intuition. Those men are as such because they have a more yechidah soul.

Grégoire Canlorbe is an independent scholar, based in Paris. Besides conducting a series of academic interviews with social scientists, physicists, and cultural figures, he has authored a number of metapolitical and philosophical articles. His work and interviews often appear in the Postil.

The featured image shows, “Young Man Holding a Roundel,” by Sandro Botticelli, painted ca. 1475.