This article was written in 1946. It’s relevance has only grown over the decades.

If a man were to say to me, “I refuse to use my eyesight except through a microscope,” I might think that the man is queer or crazy, and I would certainly try to avoid his company. Imagine taking a walk with a man who keeps one eye closed, and the other, permanently fixed to a microscope!

Such a man is worse than blind, for a blind man who cannot see the stars, talks about them, and eagerly seeks to learn; but the man tied to the microscope neither sees nor seeks. The blind man knows that he is blind and acts accordingly, but the man with the microscope thinks that he is the only one who sees, and if you dare to mention the sky before him, he says, “But where is the sky!”, meaning, of course, that the sky could not exist unless it could be placed in his range of vision.

Now if you take this clumsy and most unlikely illustration and translate it from the order of sense to the order of intelligence, you get one of the most common intellectual types today, the type of a mind that will not apply its intelligence except through the scientific method.

This type of mind is apt to undermine common sense, on the ground that future scientific discovery might disprove any certainty. It discredits philosophy, because the objects of philosophy (God, the spiritual soul, cause, substance, etc.) cannot be weighed or measured, can neither be reduced to a mathematical formula, nor observed in a test tube. And finally, this type of mind discards all revelation, on the ground that religion is not a channel of knowledge and that its value is purely emotional and unintellectual. This is the attitude of mind that is gradually being recognized as a cultural danger by educators and social thinkers, and is coming to be called “scientism”. Scientism is not the same as science, but is rather an abuse of the scientific method and of scientific authority.

Here are some instances to illustrate what I mean by the term “scientism”: Physicists are now being consulted, not only on the development of atomic energy, but also on the morality of dropping atomic bombs.Professional experts must now tell us, not only whether children may be exposed safely to gamma rays, but even, whether children may be exposed to sun light.

Experts must decide whether mothers should be allowed to hug their babies. Einstein is teaching, on the grounds of mathematical physics, that God is not personal. Whitehead describes the attitudes of God in terms of quantum physics. Bergson builds biology into a false metaphysical religion. Bridgman moves over from the specialized field of high-pressure physics, to define democracy, investigate the foundations of morality, and pronounce on the freedom of the will!

I propose to study in this article some aspects of scientism, this cultural disease, which I hold responsible to a large extent for the alarming number of infidels and atheists in modern universities, and for the rise of dangerous beliefs and practices, the absurdities of which could be detected by a child, but not by the involved mind of the “scientific expert” and of those who worship authority. I hope to suggest that the remedy lies in restoring philosophy to its rightful place in education.

Philosophy has been called “the Queen of the Sciences”, and indeed, the realm of the sciences left without philosophy is like the kingdom in a state of anarchy. Philosophy defends the fundamental certitudes of common sense, establishes the grounds of morality, prepares the mind for revelation, and restores order in the house of science. Let the reader then be prepared to become more philosophically minded, if this article is to make its point.

To begin with, let us observe the place of knowledge in the life of man. Knowledge is the most characteristic activity of man. A man could, without knowledge, fall down from a balcony like a fainting acrobat; but no man could, without knowledge, climb up a balcony like Romeo. When the fainting acrobat falls down, we call that an act of man, because it is a man and not a stone or a log that is falling under the pull of gravity; but when Romeo climbs up, we call that, not only an act of man, but also a human act.

Knowledge must be present in every human act: in every art or profession, in humor and in prayer, in virtue and in vice. Man cannot even commit a sin without knowledge. Even man’s beatitude is defined in terms of knowledge, for “this is eternal life: that they may know thee, the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom thou hast sent” (John 17:3). If, therefore, knowledge plays such a tremendous role in the life of man, and if the consummation of this life in the beatific vision consists in the knowledge of all truth, would it not be extremely strange if God had restricted the privilege of knowing to that very small fraction of mankind who constitute the class of scholars and scientists?

As a matter of fact, by far the greater part of our knowledge belongs to the order of common sense. Even the expert scientist could not live one single day in this world, were he to depend exclusively on his expert knowledge in this special field. And besides, both science and philosophy presuppose the great mass of common sense knowledge, and could not proceed without it. If a student comes to a biology laboratory not knowing how to distinguish between a living and a non-living thing, what would stop him from observing the properties of life in a piece of chalk?

Also, both science and philosophy use the same knowledge-seeking faculties as we use in acquiring our common-sense knowledge; and therefore, if these faculties were discredited as they function normally in common sense, it is difficult to see how they could be trusted as they function artificially in other fields. A philosopher who cannot distinguish by common sense between his head and his headache, would never acquire that distinction by studying the abstract attributes of substance and accident.

Common sense knowledge has some remarkable qualities which are easily lost when knowledge gets to be artificially methodical. To mention just one quality, common-sense knowledge is somehow complete and integral; that is to say, that in common sense, the complete man knows in a certain manner the whole of reality. Common-sense knowledge is undivided and unclassified, it is knowledge about God and about the world, about men, animals, plants, seas, lands, time, space, institutions and objects of all kinds.

Certain knowledge is mixed with knowledge that is only probable, and knowledge which comes through the senses is not distinguished from knowledge which comes through the intellect. A soldier on the front line, does not say, “Let me abstract from the noises I hear and the sights I see, and reflect on the principle of causality” nor, on the other hand, does he say, “Indeed, I hear all kinds of sounds, and see all kinds of shapes and colors, but I must not make any further inferences.”

Common sense is also knowledge within a perspective. Only God, eternal, omnipresent, omniscient, can afford to know too much about too many things, without much reference to a purpose. The man on the front line knows all reality, but only as relating to the thing at stake, his very life. And the man of common sense is constantly on the front line, the line that divides time from eternity; consequently, he must know all things as they relate to the maintenance of his life in this world, and the salvation of his soul in the next. You cannot teach the man of common sense until you get him interested, and you can get him interested only by relating all things to the ultimate purpose of his existence.

But common-sense knowledge has its limitations, as the man of common sense very well knows. By mere common sense, no airplace can be constructed, and no medical operation can be performed. When the man of common sense needs to build a bridge, he does not go to another man of common sense; instead, he uses his common sense and goes to an engineer. It must be evident, therefore, that if we would have many of the things we consider desirable, common-sense knowledge would no longer be sufficient, and scientific knowledge becomes necessary.

But the discipline that is required for the acquisition of scientific knowledge makes that wholeness, that completeness of common-sense knowledge, impossible on the scientific plane. No man can possess technical scientific knowledge about everything; and therefore, every one must specialize in that part of knowledge needed for his profession, or for his function in society. Further, in contrast with the spontaneity of common sense and the directness with which it envisages its objectives, we find that science requires intricate and roundabout processes for its attainment. This makes it quite possible for man to lose every perspective of relevance, and to proceed along blind alleys of knowledge and research that lead nowhere. And yet all this is unavoidable and follows from the very nature of science.

It would be absurd to ask a medical student to justify in terms of ultimate human purposes every single action or assignment required in his general training for his profession. Hence we have another danger of specialized training; namely, when man is trained to know a part of reality, and to deal even with this part in a manner that is systematically artifical, this man develops more as a function than as a person .

Hence, it is that science and technology carry the danger of depersonalizing social relations. But man insists on being a person and on being treated as such; and as a person, he insists on his right of somehow knowing all reality and being concerned about his destiny as a complete man. Therefore, once his common-sense perspective gets to be distorted by the artificial mold which frames his mind in a special field, he tends to raise his special and partial science up to the dignity of a universal science.

“All reality is made up of material atoms or quantums of energy,” says the physicist. “Reality is a mysterious life force, elan vital ,” retorts the biologist, who would see all things from the window of biology. All history is made by economic forces (Marx), or by sexual energy (Freud). These and similar monisms, represent some of the grave dangers of scientism.

And then we have what is perhaps the greatest danger of scientism, namely, the philosophy of positivism. The primary interest of the special sciences is not the contemplative understanding and appreciation of reality, but the control of the visible world for practical purposes. In order to harness the powers of nature, all the knowledge needed is knowledge of certain accidential aspects of material things. Such an accident as the quantity of the thing, is all that remains of reality when the real thing is replaced by a measure and is introduced into a mathematical formula.

Of course any child could tell you that the quantity of a thing is not its complete reality, but the scientific expert tends to identify the quantity with the whole thing. Hence we get those quantitative ghosts called by such names as, energy, mass, atomic number, wave length, intelligence quotient, etc., floating around the scientific graveyards where the objects of common sense are deeply buried, and parading in the garbs of the real and substantial entities.

When this tendency of the sciences is built up into a complete philosophy, a world view, which denies the substance of things, denies the reality of causes, and admits only those surface accidents or appearances of material things which can be measured and made subject to the scientific method, when this thing happens, we get that most negative of all philosophies, namely, ironically enough, the philosophy of “positivism.” Now neither God nor the spiritual soul of man can be made subject to measurement or to test-tube analysis. Therefore, the positivist rejects on principle, all metaphysics and all religion.

But now, having seen some of the dangers of scientism, let us proceed to study the nature of science. This will lead us to determine whether philosophy is a science. The Greeks and the scholastics considered philosophy the science par excellence , but to the modern mind, this view cannot be taken for granted; it has to be justified.

What is a science, and how does scientific knowledge differ from the knowledge of common sense? The most superficial observation reveals to us that what we call sciences possess a certain form and order, i.e., they are organized bodies of knowledge and not random collections of facts. Now this order of the sciences is not imposed on them externally like the alphabetical order of a dictionary. It is an order which mirrors and reveals the order of real things.

The sciences have order because they put things together as things flow from common origins, principles, or causes. Science begins as soon as things begin to be systematically and methodically explained, and the more explained things are, the more orderly they appear to be. Man, therefore, can be said to have sciences, because he asks questions and seeks explanations of things that fall within his experience. And man is a great “question-asker.” As a matter of fact, man is the only question-asker in the whole universe. You could almost define man by this property, which flows from his very essence.

Now here is the reason why man asks questions. The human mind is made for a reality which is absolute, necessary, and simple, and which contains the sufficient reason for its being. This reality is, of course, God. Once the mind sees God, our intelligence is so thoroughly satisfied that it can raise no further questions, because no problem or mystery remain, either in God Himself, or in anything He caused. But when the human mind is confronted with a contingent reality which does not possess within itself a sufficient reason for its existence, the mind immediately tries to explain this reality, and explaining a thing means reducing it ultimately to a cause or principle which does not need to be explained.

To put what we have just said in more philosophic terms, we could say that the mind knows with absolute certainty that there must be a sufficient reason for everything that is. If we didn’t know that, we would never seek the “why” of a growing tree or of a falling apple. Every single science in the world owes its existence to this thirst for explanation, which all men share. This thirst for explanation is in our intellects and not in our senses. Animals never ask questions and never attain science. The stream of sense experience received in my skin from a flowing river does not raise any questions, but the notion of movement abstracted by my mind raises the problem of change, and starts the mind along the track of science.

The number of the sciences could be very large, because in addition to the great variety of objects that could be studied scientifically, there is a great variety of aspects from which to study things. A chair, for example, could be studied in physics, in chemistry, and in economics; and man may be studied in anatomy and in politics. In each case, the material object is one, but the formal object different.

But this variety of the sciences forms a natural hierarchy. For example, biology is superior to bacteriology, physics to metallurgy, astronomy to navigation, and economics to banking. What determines this hierarchy? The principle of explanation, in which the very essence of science consists. The superior sciences come closer to giving an ultimate explanation.

In every case mentioned so far, the superior science explains the principle of the inferior science, and defines its basic concepts. Hence, the inferior science of each pair presupposes the superior science, and depends upon it for being a science at all. Metallurgy presupposes the ordinary laws of general physics (such as the laws of heat and light, the principle of specific gravity, the laws of magnetism, etc.). If one were to stop and give a sufficient explanation of every term occuring in the science of metallurgy, one would have to include the greater part of general physics in every chapter on metallurgy; but, of course, physics is ordinarily taken for granted.

The hierarchy of the sciences is, therefore, a hierarchy of explanation. But along with this mark, others follow, stemming from it and depending upon it. The superior science is in every case a greater general interest and is valuable as knowledge in itself and for itself, while the inferior science is primarily of practical interest, and is valued on that account. No one studies metallurgy in order to become better educated.

Close to the top of this hierarchy, we find such sciences as physics, biology, and mathematics. Yet none of these sciences is ultimate, not even in their respective orders of knowledge. No book on geometry, for example, discusses the nature of quantity, continuity, shape, dimension, point, number, measure, space, etc. Geometry takes all these concepts for granted, just as it also presupposes its axioms and the general method of demonstration. The same could be said about physics and biology with regard to their basic notions and principles, such as the notion of matter, change, mass, energy, entropy, atom, field of force, life, generation, etc.

All these sciences, in so far as they are sciences, that is, in so far as they possess any explanatory value, presuppose the superior philosophic sciences of logic, cosmology, rational psychology and ethics. And these philosophic sciences, in turn, presuppose ontology or general metaphysics. Ontology is the absolute summit of natural knowledge; it is the one science which does not presuppose any other. Ontology studies all things under the most important aspects of all things. What ontology studies about being is more important than anything said about that being in any other science.

Is there any approach to reality more important than to study a thing in so far as it is one, true, good, and beautiful ? Supposing you take a society and remove from it all institutions and persons concerned with the attainment and expression of truth, goodness, and beauty, how much of that society is worth having? Or, let us take the history of man and remove from it the stories of its philosophers, scientists, poets, artists, saints and mystics; how much of what is left of that history is worth studying? As ontology studies all these attributes of being, it studies things in so far as they reflect the perfections of God; for God alone is supremely one, true, good, and beautiful.

Ontology thus establishes the highways on which the mind constantly travels from the world to God, and from God to the world. Moreover, ontology raises, formulates, and answers, all the most basic problems which torment the minds of men in all ages, and which underlie all great literature. Such problems as the problem of being and of change, the problem of evil, and the problem of knowledge, are solved in ontology as well as is possible for the human mind.

But then, have we any right to call ontology a science? According to modern usage, when we say science, we understand primarily something like physics, bacteriology, or perhaps even sociology. It should be clear however, from our discussion, that the notion of science applies primarily to ontology, secondarily, to the other philosophic sciences, and only in a very weak sense, to the special sciences. But since the discussion has been a little general so far, I would like to illustrate by a concrete example, the contrast between the philosophic and scientific outlooks (using the word “scientific” in accordance with modern usage).

Let us suppose that a philosopher and a scientist were to witness together the death of a man; the scientist would ask, “Why did this man die?”, and he would seek an explanation in such things as poison or heart failure. On the other hand, the philosopher perceives immediately a more fundamental problem: he would like to know, not the accidental reason why this man died, but rather why anybody should die at all.

The investigations of the scientist might contribute to the sciences and arts of medicine, pharmacy, and perhaps even chemistry; the reasonings of the philosopher, on the other hand, lead to a better understanding of a composite, material being, in contrast with a simple being, and therefore, to a deeper understanding of God and of man. Science goes hand in hand with the practical arts and artcrafts, with medicine, farming, engineering, industry, etc.; while philosophy associates with religion, poetry, and the contemplative arts.

Put in the language of philosophy, this difference between philosophy and the sciences can be expressed in the following terms: philosophy seeks the ultimate explanation, while science is satisfied with the proximate causes of things.

Now as far as the mind is concerned, proximate explanation is really no explanation at all. It explains only for practical purposes. To know that water can be decomposed into oxygen and hydrogen is useful information in case you are interested in manufacturing either of the two gases, but it certainly fails to explain the mystery of chemical union. And besides, the problems of science presuppose those of metaphysics.

Man would not seek the precise cause of malaria unless he knew that things like malaria must have a cause. For obviously the scientist does not try to determine whether malaria has a cause, but rather what the cause is. The scientist obviously knows that a contingent thing like malaria must have a cause, although he does not develop the notion of a “contingent being” and the notion of a cause, nor does he care, as a scientist, to reason out all the implications of what he implicitly asserts with regard to these notions. Were the scientist to stop and reflect on these matters, he would move out of the field of science and into the field of philosophy.

Philosophy, therefore, not only has the title to be called science, but has it in the highest degree: it is, as already intimated, the queen among the sciences. Beginning with ontology, and running down the hierarchy of sciences, we would get something like the following arrangement:

I. Ontology (or general metaphysics) of which the most important part is Theology.

II. The Philosophic Sciences (the sciences of special metaphysics): Logic, Cosmology, Rational Psychology, Ethics.

III. The Mathematical Sciences and the General Sciences of Observation and Experimentation: Arithmetic, Geometry, Physics, Chemistry, Astronomy, Biology, Politics, Economics.

IV. All the practical arts and sciences whose primary purpose is not the understanding or the explanation of reality but some practical utility. Their number is very great.They correspond with the variety of crafts and professions, especially those which are intricate enough to require the development of a science or perhaps many sciences. E.g. , all the sciences of medicine, engineering, farming, pharmacy, navigation, metallurgy, banking, jurisprudence, electrical engineering, etc.

One glance at this table reveals the root reason of scientism. The lowest order in this hierarchy of the sciences is the foundation of our material civilization: it builds our machines, runs our hospitals, and fights our wars. In order to maintain our culture we are bound to devote a great part of our time and attention to the cultivation of these lower sciences.This trend has been crowding out of existence those sciences of the highest two orders, which guarantee cultural unity and a balanced perspective.

The general science of the third order, like physics and economics, came to be regarded as the core of liberal education, but these sciences are ordered primarily to the practical interest and not to the speculative. Physics, biology, and economics are not innocent crafts like carpentry and masonry, which require the development of special skills, without distorting the truths of common sense. The latter are sciences of a kind, without being sciences to the limit. And when the mind is made to perform on the plane of science, it must either be led to final and correct answers, or find false substitutes in sophistry and ideological error.

We must restore philosophy, religion and common sense as valid means of knowledge, or else we are going to die from the sickness of scientism. It is nice to have a nose on one’s face, but when you see a nose swelling and about to efface the remaining features, you know that there is disease and danger. Culturally speaking, scientism is such a pathological inflation of science, at the expense of all other forms of human knowledge.

As for common sense, little can be done for it deliberately. As soon as common sense becomes reflective or methodical, it becomes something else; that is, it becomes either philosophy or science. Common sense cannot formulate or defend its convictions against the attacks of false philosophies and false religions, and therefore, unless the fundamental certitudes of common sense are developed and defended by good philosophy, false doctrines are bound to arise.

And as for revelation, it is foundationally in God, under His disposition; and, as long as we do not confuse ourselves by perverse use of our natural faculties, God can talk to us and lead us to the saving truth. Our own responsibility consists in using our natural powers according to the purposes intended by God, and God gave us intelligence, primarily, so that we may know Him and love Him, and, secondarily, in order that we may rule the material universe. We are putting a tremendous effort towards the attainment of the second of these objectives, but if we are to be faithful to the first objective, we must restore philosophy to its place in liberal education.

Of course, this advice cannot be given except to those who know where to find the one sound tradition of philosophic truth. This tradition is protected, and will always be secure, only in the shadow of the Catholic Church. Here is another confirmation of Christ’s promises, where he says: Seek ye first the kingdom of God and His justice, and all these things will be added unto you.

Here is another temporal problem, which shall never be solved by those who do not care to discover the kingdom of God, as it exists in this world. If the place of philosophy is usurped by the confusion of all the false doctrines and perverse opinions of all times, then certainly that kind of philosophy will offer no remedy to the confusion of scientism.

They say, “You want to bring philosophy back to the modern man; but he already suffers from the complexity and diversity of his interests. Wouldn’t philosophy add just one more item to this complexity?” This is like saying about a man trying to find his way around in a crowded dark room, “Why crowd him further with a lamp?”

For that is precisely what philosophy contributes to the complexity of modern civilization: a lighted candle in a crowded dark room.

Brother Francis Maluf was born in Lebanon in 1913 and held a PhD in philosophy. Along with Father Leonard Feeney, he was a founding, in 1949, of the Slaves of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, a religious Order. Brother Francis went to his heavenly reward in 2009. This article appears courtesy of Catholicism.org.

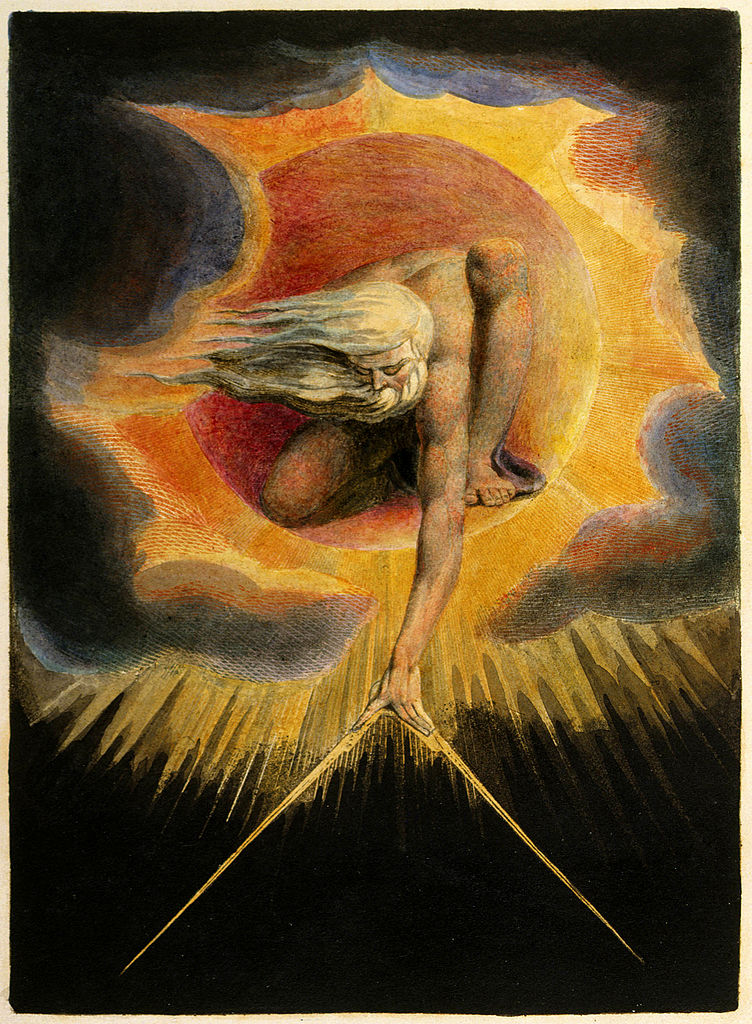

The featured image shows, “Fiat lux” (“Let there be light”), from the sketchbook of Francisco de Holanda, dated 1545.