In Alsace, doing a retreat with monks is not an easy thing to do. The misfortune and turmoil of the Wars of Religion set this region ablaze, with its scenes of ravaged abbeys, massacres of monks, and forced exile. Ecumenism started rather badly. The Cistercian abbey of Our Lady of Oelenberg retains yet the presence of the monasteries of yesterday.

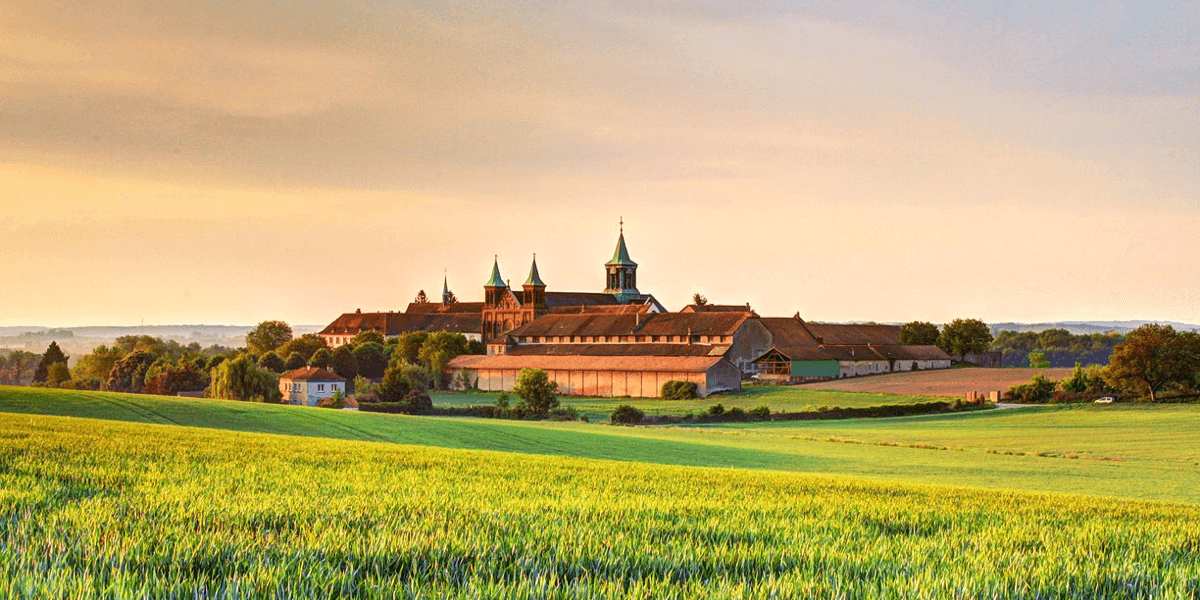

We have to follow the great blue line of the Vosges, cross Mulhouse, the city of blues, its factories, its industrial works. On the plateau of Réningue is the abbey, situated on a hill, bordered by the Oelen. It is an extensive building, with farmhouses forming a wall. A small Jesuit chapel with a pointed roof stands out and the basilica is enthroned in the center, topped by two grey-green bell towers, admirable for its standard facade of brown tanned sandstone. The whole abbey is situated on a long strip of land where the potato fields never end. The paths, traced out to the rule, go on without you seeing the end. The water-logged holes in the soil are iced over. The snowy mountains, in the distance, are an elusive decor; the Mongolia of the Sundgau. At this time of year, a bitter-cold hits the face, freezes the tractor tracks and the horses’ hooves in the hard earth. The pale sun promises beautiful shades, plays with the gray clouds, delights the morning with a clear, egg-yellow light, and the afternoon with an exquisite clementine orange.

The interior of the church is a neo-Romanesque construction, made of lime and sandstone, with a choir similar to the basin of the municipal baths of Strasbourg, from the beginning of the 20th century, and surmounted by a Virgin and Child, noble and fat. The stained-glass windows, made of orange diamonds, diffuse a peaceful light. The monks’ stalls are carved in Alsatian woodwork; some sculptures show two monkeys scratching their heads—a warning to distracted monks—one carved brother is stabbing the devil in the back, another is snoozing on a barrel.

Oelenberg suffered through the war. In the basement, cellars and a subway entrance were built by the poilus who numbered 1500 and were stationed at the place where the abbot-fathers rest eternally. In 1945, the French defeated the Krauts in the abbey, at the cost of deaths that the Blue Devils wearing their pie-hats honor every year. A proud and virile military choir resounded during the Saturday mass, sending shivers down your spine.

Oelenberg Abbey is huge, the corridors resemble those of the old elementary school, of my childhood, of yours, dear readers, with its small mosaic floor, its green-water walls. In the old days when there were many monks, they ate in a refectory famous for its central stained glass window representing Christ on the cross and for a series of paintings on the life of Saint Bernard of Clairvaux. The place has become a vast library where in turn one picks up Yves Chiron, Joseph de Maistre, Origen and Jacques Maritain who is buried in Alsace.

Behind a heavy door, in the first part of the monastery, is the Jesuit chapel, built in homage to Leo IX, the Alsatian pope from Eguisheim. The Renaissance crucifix is a Germanic masterpiece.

The body is imposing, massive, the ribs slumped and drawn, the arms muscular, the fingers enormous, the legs athletic. The blood flows from the loincloth of Christ, thickly. You have to approach under the Lord’s cross, under the crown of thorns, if you go to the left, the face is slack, it is dead; if you look to the right, Christ smiles, seems to live. Death conquers the true man, but the true God already triumphs over death.

There are only ten of them left now. They were one hundred and fifty in the last century. Ten monks live here; for such a big place, it is truly incredible. They are white and black shadows that we never meet, busy in this cold, decrepit legos game. Like the factories without workers that are said to be deserted, it could have been the deadly fate of this last abbey to close up shop, to end up as a museum of slippers or chocolate if some vocations given by the Lord were not going to, at least, ensure a small relief. Two robust, sturdy novices, in no way comparable to the products of the globalized metropolis, are there; one looks like a young Solzhenitsyn, the other like a rugby player.

We are first welcomed by a gentleman, Bertrand, who is very simple. In my life, I have never known a man so gentle and so good. He has the sanctity of those who have fallen six times and risen seven. He is an old man, humble; his look is that of a lamb; his eyes blue like the calm sea. He pats you on the shoulder, pats you on the back, is devoted to you, concerned like a father for his children. He is the pure heart of the Beatitudes, the satisfied, the peacemaker. Before leaving us, this man who gets up early, at matins, to prepare the table for the retreatants until the evening of compline, tells us, “With God, no compromise;” and adds, “Do not seek to please men, please God.” A radical Christian.

Father Dominique-Marie, the Abbot, goes from one door to another in his white robe. He has the look of a wise man. His voice is restrained, calm, always well considered. A former schoolteacher with an old-fashioned beard, he entered the monastery in his fifties, anxious to observe the three precepts of the rule of Saint Benedict: obedience, stability, conversion. This man was converted. Converted? But wasn’t he already a Christian? The conversion of which the Father-Abbot speaks is that which consists in putting God at the center of everything that links love, beauty, the arts, joy. There is a gentleness, a lightness and a surprising familiarity in this abbot. He is easy to talk to; he visits you at the retreatants’ table, accepts a piece of cake, refuses to have his ring kissed. He is a religious open to progress, to dialogue, but without this becoming an untenable “nevertheless.” He is resolutely critical of the consequences of the great liturgical and religious choices of the last Council and can only observe the fall, with fifty years of the practice, of the Catholic faith during Masses where there have sometimes been quite a few abuses, in an effort to make a fresh start.

In the winter chapel, the offices are said simply, in a limited Gregorian style that pierces like the arrow that is not heard as we hope in the great Latin spectacle of other abbeys. The prior, a very old monk, Agecanonix in a gown, who walks around with a walker, gives the first note, ahead with the music. And the service is like a small river among the mountains, where pebbles roll in a stream, pushed by the whistling of the wind in nature.

If Bernard Pivot were to give me his Questionnaire again, from the time of Bouillon de culture, to the question “The sound and noise you prefer?” I would gladly answer, “The bell that strikes in the night to announce matins.” We are roused from sleep and from bed. Psalm 3, sung at night, has an invigorating and pacifying effect on me. David flees from his son Absalom and says, “I awake: the Lord is my help/ I will not fear this many people/ who surround me and come against me/ All my enemies you strike in the jaw/ The wicked you break their teeth.” The God sung in the psalms delights me. He is good like a father, loving and stern. He embraces you and does good; performs wonders and breaks necks. It is good to start the day with a banner and a God who does not balk.

At the table, the encounters are original and also testify to the diversity in the unity of the Church. Yes, it is good for traditionalists to meet brothers in the faith who do not practice the same form, do not always think alike. A husband is preparing to be a deacon, only hears zilch in Latin, gets tense at the idea of prayers downstairs in the hall, doesn’t understand that if he can be a deacon it is because vocations are dwindling like snow in the sun; a ninety-two year old Swiss grandmother spends her vacations; a younger woman, so like a character in a Houellebecq book, came to take stock of her life; a good father who is expecting his fourth child came to recharge his batteries, baptized in the Jordan River, capable of crying when he talks about Christ.

During this short retreat, I still wanted to penetrate the mystery of this total conversion that the monks seek, I wanted to feel the mystery of faith, and, without having understood it yet, I draw as near as I can.

Nicolas Kinosky is at the Centres des Analyses des Rhétoriques Religieuses de l’Antiquité. This articles appears through the very kind courtesy La Nef.