The Chenoboskion-Nag Hammadi manuscripts are leather-bound codices (papyri, that is), dating from the middle of the 4th century AD, and found in 1947, northwest of Luxor, by Egyptian peasants, and since then kept at the Coptic Museum of Cairo. These compromise twelve papyrus codices, plus the remains of a thirteenth, totaling nearly 1,300 pages and over fifty Coptic texts, most of them completely unknown. Only one of these codices was acquired by the Coptic Museum in Cairo, as early as October 1946; it was not until 1975 that the entire collection was assembled there.

The result of a fortuitous find, the discovery of Nag Hammadi early aroused the attention of both antique dealers in Egypt and the authorities of the Coptic Museum. It was not one of those theatrical finds, which officials, journalists and the curious flock to. As with the Desert Scrolls of Judah (commonly referred to as “the Qumran”), almost all episodes of this discovery were suppressed, and almost all details of the history and actual content of the manuscripts have long remained unknown to this day.

Be that as it may, a whole apocalyptic and Gnostic literature then emerged from the earth. The direct sources that were so sorely lacking in research were finally found.

The first Europeans to have knowledge of the discovery were French personalities or scientists. This discovery involved several things: the search for the manuscripts dispersed by the peasants who had exhumed them; field investigations to find out the location of the find; the first readings of the pages less damaged by time; the identification of the writings that came to light there and the first inventory. All of this was the work of Jean Doresse (1917-2007), the main witness to the first stages of this major event in the history of research.

After auditing the lectures of Henri Charles Puech (in the section of religious sciences of l’École pratique des Hautes Études), Doresse joined the CNRS in 1941 and became a research grant holder in October 1944. In September 1947, he found himself in Egypt, in order to carry out, as “excavator for the Louvre museum,” the first of five missions, financed by the Archaeological Excavations Commission of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In October 1947 (he was thirty years old), he informed C.H. Puech of the existence of a papyrus volume,140 pages long and containing Gnostic writings in Coptic Sahidic (the current Codex III). Thus began an exchange of correspondence (which lasted until 1970) between the young researcher, who had privileged access to the manuscripts, and the recognized scholar who, although unable to read or translate the writings, was nevertheless best able to interpret them.

A scientific committee made up of various personalities was then created with a view to publication. It consisted of Doresse, of course, along with Togo Mina, curator of the Cairo Museum at the time of the discovery and who first recognized the importance of these manuscripts, Canon Drioton, renowned Egyptologist and director of the Antiquities Department of Egypt until 1952, Charles Henri Puech, arguably the best specialist in Gnosis and Manichaeism, and Walter Till, the specialist in the Berlin Codex. But bad luck of “an evil sort” (to use Doresse’s own words) would plague what concerned the acquisition and publication of these ancient documents. Two years in to the work, Togo Mina died in 1949; he was always hounded by the thought that these manuscripts would disappear from Egypt, and he thus made Doresse promise to protect them from the inevitable greed.

In 1958, Doresse published, Les livres secrets des gnostiques d’Egypte (The Secret Books of the Egyptian Gnostics), the result of archaeological adventure with multiple twists and turns; the book went through several editions. According to Doresse, “the style [of the book] reflects the fever of the time when the characters involved in this find were still alive.” He presented the 44 unpublished Gnostic treatises, narrated the adventures of their discovery, the vicissitudes of their purchase by the Coptic Museum, and then he explained the unfortunate delays in their publication – revolutions and wars are not favorable times for archaeologists.

After gathering all the information provided by the heresiologists and quickly pinpointing the gist of the already known Gnostic treatises, he proposed a provisional classification of them into four categories: prophetic revelations; pseudepigraphic writings taking on the aspect of Christian writings; gospels of a Christianized gnosis; and finally, those treatises more or less close to hermetic writings. He summarized the content of each treatise, by first trying to identify it, often successfully, by way of the information provided by Irenaeus Epiphanes and the Philosophumena.

Doresse also spoke, in a veiled manner, in the introductions to each of the new editions, of the harmful consequences of this discovery for his own existence and his career. The Secret Books of the Egyptian Gnostics was planned as a trilogy, the first volume of which was then titled, Introduction aux écrits gnostiques coptes découverts à Khénoboskion (Introduction to the Coptic Gnostic Writings Discovered at Chenoboskion), and published in Paris, in 1958. Two other volumes were planned. Doresse then outlined the main features of a Gnostic doctrine by taking up a suggestive study by Henri Charles Puech, la Gnose et le Temps (Gnosis and Time). From the start, Doresse understood that these texts from Chenoboskion, much more numerous and evocative than those of Qumran, had greater historical significance.

Like the Qumran manuscripts, they relate to an age which, for the development of human consciousness, remains the greatest. This is the moment when the individual found himself most intensely placed before the problems of personal destiny and the destiny of empires and civilizations, which he regarded as definitely established. The central moment for these ages is the Cross. We know this today, but that age was the first to say it – we were in the presence of a veritable library that attested to the existence of a Gnostic Church which maintained links with groups located in other regions.

Very quickly, Doresse formulated the hypothesis that in all likelihood these were documents from the library of the monastery of Saint Pachomius, hidden there at the end of the 4th century, after the prohibition on Gnostic literature by Athanasius of Alexandria, and by the decrees of Emperor Theodosius I.

The Gospel Of Thomas

Such a discovery was not without consequences. Gnostic studies were soon drawn into an ever-expanding whirlwind that was difficult to curb. The eye of the storm was the Gospel of Thomas.

The more or less Christian apocrypha, used by the sectarians of Chenoboskion, was then given the authority of well-known apostles: James, Thomas, Philip, Matthias, John and Peter. The content of these texts is often trivial, not fundamentally contradicting that of the canonical Gospels, but distorting Christian doctrine and deviating from it. In general, the Gnostics of Chenoboskion wanted to introduce into their doctrine a false Christianity by hatching so-called Gospels put under the names of the Apostles, or even by placing certain revelations in the mouth of the Savior. Basilides had also fabricated a compilation of this kind.

Among these adulterated Gospels, the Gospel of Thomas made a lot of noise and gave rise to many rumors, not always of good quality. Many newspapers of the time argued, on the strength of false, distorted, or misinterpreted news, that this was nothing less than a “fifth Gospel;” that it revealed “unknown facts” about the life of Christ; or that it seemed “almost certainly” translated from Aramaic.

C.H. Puech then pointed out, rather fittingly, that to speak of a “fifth Gospel” did not make much sense. If we believe this to be so, then we would have to exclude the four Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke and John) whose authority and authenticity has been determined by the Church. Or, we would have to recognize all works of the evangelical type as “gospels,” whether or not they were canonical; and we would then be dealing with an abundance of extra-canonical texts. And in that case, why give only a fifth place to the Gospel according to Thomas, or reserve that spot just for him, rather than any other work of the same sort?

This Gospel of Thomas is, in fact, nothing more than a collection of one hundred and fourteen logia; but it is the largest collection ever transmitted of the “Sayings of Jesus,” or “Words” attributed to Jesus. After a short preamble of four and a half lines, (and which already contains the first logion), the text is just made up of a series of sentences or words independent of each other, mechanically juxtaposed, outside of any systematic narrative-frame, and most often introduced by the stereotypical formula: “Jesus said.” An exordium which itself seems fictitious (no doubt added afterwards) specifies that these are the secret words that Jesus the Living said and that Didyma Jude Thomas wrote. It is written in Sahidic Coptic, and dates possibly from the second half of the 3rd century or, according to other specialists, from the 5th century.

Complete and written with admirable care, the Gospel of Thomas is the second of seven writings in the collection, where it appears between the long version of John’s Apokryphon and another apocryphal piece, the Gospel According to Philip. It is “apocryphal;” in other words, an esoteric text, or which takes itself as such, and which claims to record hidden, secret words, namely, words of Jesus. It is also a pseudepigraphic work since, despite its title and its preamble, both obviously fictitious, the writing cannot be traced back to the apostle, Didymus Judas Thomas. Far from uncovering unknown aspects of the life of Jesus, it presents no historical or narrative character; nor does it contain any account. And, if it relates some act of Christ, it is in an exception and merely schematic. Apart from the few lines at the beginning, it is exclusively made up of a series of words attributed to Jesus and placed end to end. Not a single one of these Words has any chance of going back to an Aramaic prototype.

Indirect sources knew of the existence of this gospel, but what is said is very vague or confusing. According to a tradition reported in the Pistis Sophia, Jesus would have, after his resurrection, entrusted to Thomas, as well as to Philip and to Matthew (or rather, as Theodor Zahn conjectures, to Matthias), the charge of relating all his actions and to record all his words. The three apostles, or disciples, would be the three witnesses whose testimony, according to Deuteronomy 19:15, and the Gospel of Matthew, would be necessary for the establishment of the truth. Thus transformed, at the whim of the Gnostics, into those of essential intermediaries, if not exclusive guarantors, of the authentic transmission of the integral and hidden teaching of Christ, their names – one could imagine – must have served to legitimize the fundamentals of the Gospels.

The introductory lines of the Gospel of Thomas can also be read, exactly reproduced in Greek, on the back of a papyrus of the 3rd century, unearthed in 1903, namely, Oxyrhynchus Papyrus No. 654. The papyri of Nag Hammadi, in fact, have made it possible to complete and rectify the Oxyrhynchus texts.

But are both the 3rd century papyrus and the Gospel of Thomas inspired by the same tradition? This is the first important question. Another is even more crucial – are all the words of Jesus collected in this Gospel, or, at least, some of them, “authentic?” Can they be traced back to Christ himself? Origen asked himself this; and with regard to one of the Sayings in this collection, Saint Jerome had to admit that there could be “gold in this mud.”

Although refusing all canonical authority to the apocrypha because of the falsehood that abounds in them (propter multa falsa), Augustine recognized that we sometimes find “some truth” in there. Puech’s response is cautious. If there are strong reasons to be assured of the inauthenticity of many of these new Sayings, all that we can do about those ones that give us pause is to establish, by more or less fragile criteria, that it is not impossible to suppose them to come from the tradition – written or oral – of contemporary Christian communities or close to the apostolic age. But, from that to concluding that they go back to Jesus Himself is leap into the unknown, the unverifiable. The Christian Church is founded primarily on authority, as was the Synagogue. The truth is what was taught by the founder and which is binding on the believer. Hence the need to know what Jesus said and what his immediate disciples heard.

However, a good number of Manichean texts exhumed, either in Central Asia or in Fayum, cite Words of Jesus which are found exactly, or with some variations, in the Nag Hamadi Library. In particular, we have only to compare the beginning of the Letter of Foundation (Epistola Fundamenti) of Mani, and the prologue to the Gospel according to Thomas, as it is restored to us, to be convinced that the founder of Manichaeism knew the same writing and was inspired by it on occasion.

But to work on a text, you need a translation, and the translation of the Gospel of Thomas was slow to appear. Years passed and the editorial work still had not borne fruit. In 1959, Jean Doresse then published L’Evangile selon Thomas (The Gospel According to Thomas), Volume II of work that began with Les livres secrets des gnostiques d’Egypt (The Secret Books of the Egyptian Gnostics). This scholarly work of his provided researchers with a working text. Three other editions were published at the same time as the French edition: English, German and Dutch.

But by publishing this work, Doresse pulled the rug out from under Puech. The following year, Puech published a so-called “critical” edition with three other researchers, all well-known scholars. They were in such a hurry to publish that they did not wait to include with the text and its translation the critical commentary which they were preparing or claimed they were preparing. The stakes were indeed high as to which would be the preferred scholarly reference edition, cited in prestigious journals, along with the name of the editor or editors.

By this time, however, Jean Doresse had already moved on from all this, having understood that it was all needlessly contentious, and had begun work on Ethiopia.

International Greed And The End Of Certain French Research

The first editorial project was not brought to a halt by Togo Mina’s death in 1949, as Professor James M. Robinson claimed. Rather, the project was hijacked by international passions, in particular Anglo-Saxon, which also put an end to French research that had remained of Christian and Catholic inspiration.

In the early 1960s, the Director General of UNESCO, the Frenchman, René Maheu, concluded an agreement with Saroite Okasha, the Minister of Culture, and the National Council of the United Arab Republic, to publish a complete edition, edited by an international committee, chosen by Egypt and UNESCO. But when it became known that several of the selected texts were already the subject of a publication project, the UNESCO endeavor was reduced to a facsimile edition which, in turn, remained more or less dormant.

Progress was not made until 1966, with the first International Colloquium on the Origins of Gnosticism, organized in Messina, at the initiative of Professor Bianchi, and which came at the end of three years of preparation. At the Colloquium, held from April 13 to 18, 1966, sixty-four topics, all mimeographed and distributed three months earlier to all registered participants, were discussed at length.

During one week and in general assembly, ten areas of research were reviewed: the current state of Gnostic texts; the definition of Gnosticism; Gnosticism and Iran; Gnosticism and Mesopotamia; Gnosticism and Egypt; Gnosticism and Qumran; Gnosticism and Judaism; Gnosticism and Christianity; Gnosticism and Hellenism; Gnosticism and Buddhism. The result was a document, which was first submitted for discussion and then went to approval by the participants. Then it was published in Italian, French, English and German, with a series of proposals concerning the scientific use of the terms, “gnosis” and “Gnosticism:”

“Gnosticism” – a term of modern creation – defines a movement of thought centered on the notion of “knowledge” (in Greek, gnôsis) which developed in the Roman Empire during the 2nd and 3rd centuries. On the other hand, the term “gnosis” – whose use is attested since the 2nd century indicates universal tendencies of thought which has in common the notion of knowledge, from which, for example, also derive movements as diverse as the Kabbalah, Manichaeism or Mandaeism.

While relevant, this distinction is not widely accepted today. A pity, as it does reflect the historical reality of the great constructions restored by the Apologists; and it does make it possible to account for gnosis as an anthropological phenomenon – the same leaven making bread of different shapes, often bewildering, baked with adulterated flour, and in general, largely inedible.

The Colloquium, at least, gave occasion for direct contact with the vestiges of Egyptian monasticism: an immense religious domain, extending over twenty kilometers in length and which contains the ruins of a set of more than seven hundred monasteries and hermitages erected from the 4th to the 9th century. The delegates spent a day in Wadi Natrun and visited three of the four Coptic monasteries that remain in the Nitrian Desert. They were delighted that the monastery of Saint Macarius, reduced to six old monks by 1969, had then more than forty. What now remains, however, is a long way from the fifty convents, most of which founded in the 4th century, which covered the site, and attested to the flowering of Christianity, as well as to the destructive power of Islam.

In 1970, UNESCO and the Egyptian Ministry of Culture founded the International Committee for the Nag Hammadi Codices and appointed Professor James M. Robinson, an expert in religious sciences as secretary, which made it easy for him to supervise the project, in collaboration with the Institute for Antiquity and Christianity at Claremont (California). The Facsimile Edition of the Nag-Hammadi Codices was then published by Brill, and Harper and Row, in 12 volumes, between 1972 and 1984. Robinson then edited the American edition of these texts, completed in 1995. He was then closely associated, as editor general, with the publication of another collection of manuscripts of great importance for the study of Judaism and Christian origins, that of the so-called “Qumran” texts.

In 1987 a new English edition was published by the scholar Bentley Layton (Harvard University), entitled, The Gnostic Scriptures: A New Translation with Annotations. The volume included new translations of the Nag Hammadi manuscripts, and also extracts from heresiarch authors and other Gnostic texts.

UNESCO Takes Over

In 1973, a new project took shape, a French one, this time. Professor Jacques-É. Ménard made numerous visits to the theological faculty of the University of Laval, at the invitation of Professor Hervé Gagné. It was only a matter of translating and editing the texts of Nag Hammadi into French. He considers the Gospels to be a matter of literature. Administrative responsibility for the first Quebec team was entrusted to Hervé Gagné, and Jacques-É. Ménard was appointed as the first principal researcher and scientific director of the project (he did also form and lead a team in Strasbourg). Michel Roberge was appointed as the second principal researcher, with the task of leading the Quebec team. The list of company employees varied over the years, among them Louis Painchaud, Anne Pasquier, Paul-Hubert Poirier and Michel Roberge.

This joint project between France and Canada aimed to produce, in separate booklets, critical editions of each of the Coptic texts of Nag Hammadi and Berolinensis Gnosticus 8502, accompanied by original French translations, followed by commentaries, indexes and a general index to the entire collection. The delays were chronic, and in the opinion of the Quebec team the French contribution did not match their commitments. In France, Jean-Pierre Mahé, director of studies in the section of philological and historical sciences of the l’École pratique des Hautes Études in Paris, Annie Mahé, as well as Bernard Barc, of the Jean-Moulin University of Lyon were early collaborators. As well, there were Einar Thomassen from the University of Bergen, Jean-Marie Sevrin, from the Catholic University of Louvain, and John D. Turner from the University of Nebraska at Lincoln.

Despite the delays, an international network was set up, with French, as well as Belgian, Swiss, German, Italian, Norwegian and American, researchers. More than ten Quebec researchers and as many foreign researchers, historians of religions, biblists, philologists, Hebrew scholars, linguists, or specialists in ancient Christian literature, contributed directly to the three sections of the collection, Coptic Library of Nag Hammadi, published jointly by the Presses de l’Université Laval and Peeters of Louvain.

As well, a team of German academics, located in the former GDR, and composed of Alexander Bohlig and Martin Krause, as well as New Testament specialists, Gesine Schenke, Hans-Martin Schenke and Hans-Gebhard Bethge, prepared a German translation of the texts, which appeared in 2001, under the aegis of the Humboldt University in Berlin. From 1977, Laval University worked on a French edition of these texts under the editorship of Louis Painchaud, in a collection intended for scholars, namely, le Bibliothèque copte de Nag Hammadi (The Coptic Library of Nag Hammadi). It was not until 2007 that the Pléiade edition appeared, by Gallimard, under the editorship Jean-Pierre Mahé and Paul-Hubert Poirier.

But in 2008, there was a new publication, in French, in the form of small pamphlets authored by Professor James Robinson, in the Jardin des livres collection. The back cover blurb was oddly sensational:

In 1945, manuscripts (revolutionary for Christianity) resurfaced in Egypt, in Nag Hammadi. But since their discovery, a sort of veil has covered their content since only specialists and enthusiasts know them. However, their importance is capital, because they complete the four Gospels of Mark, John, Matthew and Luke. It took the film Stigmata and the book The Da Vinci Code for the world to discover the presence of Mary Magdalene with Christ. the Jardin des livres collection is very proud to finally publish the work of Professor James Robinson, the great world specialist.

The world was supposedly “discovering” the presence of Mary Magdalene with Christ… The world had been aware of the presence of Mary Magdalene for two thousand years already. The nature of this presence, of course, varies depending on whether it is discovered under a Christian or a Gnostic propensity.

Each booklet was preceded by a long introduction by Professor Robinson, who described, with great precision, the conditions of the discovery (which Doresse never described with such precision), and Robinson gave the framework of the research. Then more sensationalism, to say the least:

And it was precisely through the exclusion of these texts and others of the same kind that the Jewish and Christian canons were formed. The second reason is that these texts were probably considered sacred by their ancient users, on par with the canonical Scriptures, if not more so. The third, which we tend to forget, is that these texts come back to life in contemporary religious culture. The Bible and the texts of Nag Hammadi are inseparable like the inverse and the reverse of the same tradition…

This is how the idea arose that Christianity was in a way a “gnosis” which gained succeed, with the corollary that the Catholic Church carefully concealed the evidence by preventing access by the faithful to these marvelous texts which contain hidden splendors.

But undoubtedly more seriously, this orientation of research has buried real perspectives opened by Doresse and Puech on the links between Gnosticism and Manichaeism.

Gnosticism And Manichaeism

By the discovery of the Chenosbokion manuscripts, the image of founders and their great Revelations was entirely shaken: they were no longer named Valentinus and Basilides (Alexandrian Gnostics that the heresiological Fathers had fought), but Nicotheus, Zoroaster and Zostrianos, Seth and Adam. Unlike the two Hellenized Alexandrians, the men who claimed to confer on these texts a status of great revelation most often concealed themselves under prestigious names, while the others taught under their own name, and no doubt wanted to be founders of schools.

We must therefore admit two successive moments in the history of Gnosis and Gnosticisms, and which perhaps have no close links: a pre-Gnosis which did not know Christianity and is supported by great names of “initiates” (and called to a great future), and a Gnosis, which was later more closely linked to Christianity and less discreet because it assumed itself as a clear rival. Pre-Gnosis, which perhaps preceded Christianity, preferred to remain discrete and in the shadows. While this pre-Gnosis was dying out in Egypt, when Pachomius launched Coptic monasticism, the great Alexandrian Gnosticisms took off in Eurasia, where they would meet Manichaeism and perhaps even Mani or his first disciples. The Acts of Archelaus (a work dating from the first quarter of the 4th century) is one of the main Christian works directed against the Manicheans, in which the author evokes a controversy that opposed Mani himself with the bishop of Kashqar in Mesopotamia. After the presentation of these discussions, the bishop recounts the life of Mani as well as that of his writings and we find in this part of the text a very precise passage on the Persian doctrines to which Mani would have resorted, as did also the Gnostic Basilides, one of whose works the bishop quotes.

Essentially, most of the Chenoboskion manuscripts do not belong to the Gnostic currents known to the Apologetic Fathers but to a current called “Sethiianism,” named after one of the alleged editors:

What forms the primitive basis of the doctrine of our Gnostics of Chenoboslion seems to be this set of revelations of Zoroaster and Seth, initially independent of Christianity, which may have arisen from daring speculations on the Old Testament.

These Gnostics had taken, it seems, something from a very particular literature of which only scraps now remain: writings composed in Greek and placed under the names of the Magi Zoroaster, Ostanes, Hystaspes, writings inspired by Iranian beliefs. From this literature arose a number of increasingly confused traditions, where Zoroaster, on occasion, changed faces to identify with the prophet Seth, son of Adam, while his descendant Saoshyant, became a figure of Jesus. This would explain why the Gnostics put some of their now lost writings under the names of Zoroaster and Zostianos, as well as of Seth and Adam.

It should also be remembered that we do not know much for sure about this mythical Zoroaster and the religion he founded, except that it is a Mazdaism reformed by a great religious genius (between a mage and prophet) about whom little has been written but much fantasized. As for Manichaeism, it is the sect founded by Mani (215-276), and which took an impressive rise in all of Eurasia. Mani claimed to be at the same time Buddha, Jesus and Zoroaster. An astonishing religious personality, he drew his doctrine from the few teachings of Baptist sects then active in Mesopotamia, (including the Elcesaites, in which he was educated, and is regarded as a Gnostic sect), as well as from Iranian mythical elements, and all blended with a very large part, the most important, of Gnosis which he knew directly.

Doresse summed up this complex story as follows: one day Manichaeism (the doctrine of Mani) came; he assimilated the main elements of expiring Gnosticism thus continuing them; he then transmitted them with his own doctrines in the Middle Ages.

At the end of the second century, with its more or less hidden multiform sects, Gnosis contaminated the entire Mediterranean world. Manichaeism appeared at the time when the great Alexandrian Gnosticisms disappeared, or more exactly spread into Eurasia where they disappeared. In reality, they undoubtedly disappeared less than melted into Manichaeism, attesting to this trait which is peculiar to it, as to Buddhism; a formidable lability, a capacity to penetrate into any apparently foreign body and to find its place there. We know that Mani claimed to be the Buddha, Jesus and Zoroaster. He thus assumed in his modest person the totality of religious history in order to bring it to the fulfillment it calls for.

When and how, then, were Christian elements, some authentic, others fictitious and fabricated, added to the oldest writings? Because it was from such a meeting that gnosis was authentically and definitively born, and without doubt, it should be pointed out, the Alexandrian Gnosticisms of the 2nd century (Basilides, Valentinus, Isidore, Marcion). There are better questions to ask. Is the Gnostic current of Chenoboskion rooted directly in Christianity already established in the manner of the great Alexandrian Gnosticisms (Basilides, Valentinus, Isidore), which founded a community after their excommunication from the Church? Is it transplanted directly into a composite, syncretistic soil? Is it related to currents of Judaism or to a specific rabbinical current, which we now know to have developed what is called “gnosis?” So-called primitive Christianity, in other words, apostolic, was already quite consistent, but it had given rise to all kinds of comments, questions, and also counterfeits. These Gnostics were able to draw inspiration either from these counterfeits or from apostolic Christianity which they then transformed substantially for their own ends, by mixing in Iranized or Egyptianized apocalypses.

The literature of these Lower Egyptian Gnostics includes great apocalypses presented as though composed in earliest times and kept under the care of fantastical powers in holy and mysterious places. The setting often presents Christian or Judeo-Christian characteristics: the Temple forecourt, the Mount of Olives. Not only that but also a geography from Iranian traditions.

Did this prepare for the advent of Manichaeism? This was the hypothesis made by Paul Monceaux in 1913. It was fair, but it was formulated at a time when only indirect sources were available (the notices of the Fathers). The hypothesis fell into the oblivion of university research, the cellars of which are deep. Puech and Doresse gave it new vigor. It was, however, buried again, thus neutralizing all research on the links between Gnosticisms and Manichaeism and their development throughout Eurasia.

Alongside this hypothesis, was the idea of a Eurasian inculturation of Christianity, parallel to the first Hellenistic inculturation which also saw itself buried for the benefit of extravagances nourished by literature and cinematographic fictions.

Gnosis: The Archetype Of Excessive Noesis

According to the historian of religions Mircéa Eliade, one of the great common denominators of all religions (or invariants), is a nostalgia for origins.

All… Except Christianity.

Gnosis claims to achieve an archetype of noetic plenitude, founded among other things on the idea of unity: it is a question of going beyond – most often by abolishing – the bipolarities and dualisms in which man finds himself a prisoner, or in which he thinks he is a prisoner; the first of these dualisms is that of spirit and matter. Gnosis implies nostalgia for a primordial Time, for a first origin where the soul is generally conceived as a divine spark which has fallen into matter and which has retained the memory of this divine origin.

This idea originated in the foothills of the Himalayas, and it gave birth to the doctrines of ensomatosis. Of all the symbol-religious systems, gnosis is the one that most often has recourse to those doctrines, thanks to which man projects himself and his destiny on to the screen of a mythical time where he relives endlessly his fall into matter and his ascent to imagined celestial origins. Hence the pervasiveness of the ideas of the circle, of paradise, of the pleroma, of hierogamy by which the pneumatic joins its ontological and transcendental “I.” It is understandable that Neo-Platonism played a preponderant role in Gnostic doctrines. We can better understand the mistrust of Christian theology, Byzantine as well as Latin, for Platonic philosophy.

Even though it is based on erratic and misleading thought, “gnosis” nonetheless responds to a powerful human need: the desire for heaven. The major idea is that of an ascent to a Primordial Unity, which implies a soul journey through which man rediscovers his soul, therefore himself. All ascension literature proceeds from this chimerical aspiration.

In fact, Christianity is the best antidote to this illusion of an archetype of noetic fullness. It frees us from images of the circle, of the obsession with origins, and when it postulates the immortality of the soul, it cannot be a divine particle, but a participating rational breath. If we admit that gnosis is knowledge, we must bring to light the fundamental Gnostic intuition which constitutes the ultimate hinge of this senseless quest, and it is of the noetic type.

However, our noetics has a complex philosophical history, since it inherited jointly, but not in the same proportions, nor at the same historical moment, from Aristotle and Plato. It was not until Thomas Aquinas that the idea of the substantial union of soul and body, and therefore of a soul (“form of the body,” animating principle, understood as an entelechy) was developed and formulated precisely, as being endowed with all that is necessary to live; that is to say to know God. But obviously the equipment is damaged by sin and it must be restored. When, in the quarrel with Averroes, Thomas Aquinas “bursts the Avicennian ceiling,” as Etienne Gilson rightly put it, he understood that the doctrine of Averroes, inherited from Avicennian gnosis, contained a Gnostic ferment.

Conclusion

Saint Irenaeus had seen with ironic perspicacity the nature of this spiritual charlatanism: “Nothing hinders any other, in dealing with the same subject, to affix names after such a fashion as the following: There is a certain Proarche, royal, surpassing all thought, a power existing before every other substance, and extended into space in every direction. But along with it there exists a power which I term a Gourd; and along with this Gourd there exists a power which again I term Utter-Emptiness. This Gourd and Emptiness, since they are one, produced (and yet did not simply produce, so as to be apart from themselves) a fruit, everywhere visible, eatable, and delicious, which fruit-language calls a Cucumber. Along with this Cucumber exists a power of the same essence, which again I call a Melon. These powers, the Gourd, Utter-Emptiness, the Cucumber, and the Melon, brought forth the remaining multitude of the delirious melons of Valentinus.”

Of all the elements of which Gnosticism is composed, none seems very original. The metaphysics is Neo-Platonism, with images and musings from the East, memories of Syria or Babylon. The moral is that of the Gospel, but often misguided, with Stoic formulas and tints of cynicism. The theories and rites of salvation, except for a few features which come from the Greek mysteries, are adventurous developments of conceptions which can be traced from Saint Paul to Origen. As for the mythology of Gnosticism, it is made up especially of borrowings from the old religions of the East, and marks a return to polytheism. Progress, if you will, but progress in reverse. And it is probably this mixture of Christianity and paganism, of religion and philosophy, East and West, which brought success to the Gnostic sects.

Gnostic pride has remained proverbial. Tertullian relates that they frowned in a mysterious manner when they said of their doctrine: “Hoc altum est” (This is profound).

Marion Duvauchel is a historian of religions and holds a PhD in philosophy. She has published widely, and has taught in various places, including France, Morocco, Qatar, and Cambodia.

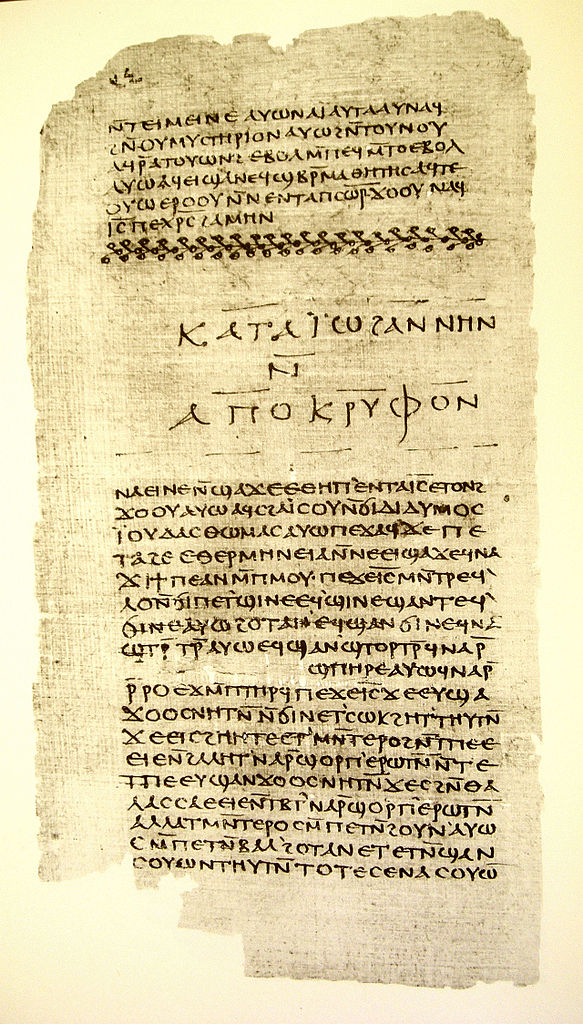

The featured image shows folio 32 of Nag Hammadi Codex II, with the ending of the Apocryphon of John, and the beginning of the Gospel of Thomas, ca. 4rth century.