In an earlier article, I described Panajotis Kondylis as a philosopher “without a mission,” in the style of his follower, Falk Horst. Horst understands this simply and plainly: While Kondylis took a critical position derived from the Enlightenment, he rejected the dream images that some – if not all – Enlightenmentists attached to their worldview.

When Kondylis developed his deliberately value-free process, he took care to bring forward an optimistic vision of the future. Such a separation can also be found in his thick volume, Die Aufklärung im Rahmen des neuzeitlichen Rationalismus (The Enlightenment in the Framework of Modern Rationalism).

This procedure criticizes left right-wing ruler, who believe that anyone who is not enthusiastic about progress has reactionary intentions. The living as well as the dead, they further believe, pushed away egalitarian values because, according to Zeev Sternhell and Jürgen Habermas, they spurned human good.

Ethnic Differences, Irrational Folk Customs, A Preference For Order

This gallery of villains includes, among past figures of thought, Thomas Hobbes, David Hume, Comte de Buffon and Herder. All these pioneers of the modern age adhered to scientific methods to the best of their ability, but ended up – viewed from the left – on suspicious terrain. Ethnic differences, the defense of irrational folk customs and a preference for a strict order of authority arise from their work.

Because of these errors, these dissident scouts received bad marks from the progressives. Kondylis’ inability to achieve a well-deserved reputation stems from his distancing from the “principle of hope” (Ernst Bloch). What is meant is the utopian fermentation agent, for which our best-known advocates of the Enlightenment advocate.

The self-proclaimed party of progress ignores the ambiguity and contradictions of the pioneers they adore. They refuse to relate their heroes to the prevailing values of a bygone age. Rather, they are putting together a pedigree for their reform work, which lumps all preferred “predecessors” together. Anyone who contradicts this transfiguration loses his place at the round table.

Kant – A Racist?

Contrary to this notion, the Enlightenment adheres to a variety of approaches that our progressive Enlightenment thinkers could hardly satisfy. Even with the typical representatives of the âge des lumières one encounters pessimistic and anti-progressive aspects, as can be read in Henry Vyverberg in Historical Pessimism in the French Enlightenment. Vyverberg examines his main theme not only in exceptional or doubtful cases, but also in figureheads like Voltaire and the encyclopedists gathered around Diderot.

Enlighteners who strongly questioned a theory of progress were not marginalized. Just as widespread among these rational people was the creation of an order of hierarchically systematized ethnic groups – an exercise that has caused consternation among today’s do-gooders. Kant, for example, in his anthropology saw colored people as less developed than Europeans.

Most of the deceased Enlightenmentists would not have adapted themselves better than Kondylis to the templates of our progress priesthood. The endeavor to lure the Germans away from their special path also refers to carefully selected progressive traditions that some re-educators want to impose on their compatriots. However, pieces of evidence that clearly show that even among Western people of reason, “retrograde” positions can easily be found.

Voltaire And Democracy

For example, Voltaire turned up his nose at democracy, continually mocked the Jews and glorified Frederick the Great as the most sensible ruler par excellence. Furthermore, the advocate of natural rights and the social contract, John Locke, wanted to keep atheists and Catholics away from his desired civil society.

In the basic constitutions of the Carolinas, written by Locke (1669), this precursor of the Enlightenment ensured that the settlers of a prosperous North American colony should certify religious tolerance. In the following century, Voltaire could hardly contain himself when he praised this English freedom-thinker who wanted to grant freedom of belief to idolaters and pagan Indians.

Noteworthy, however, was Article 101 in the same document, which granted the slave master unlimited power over his subjects. So powerful was this authority that the master could kill his slaves with impunity. The purpose of this is to draw attention to a truism. It is a futile task if one tries to reconcile the mental figures of a distant epoch with our late modern values.

Paul Gottfried, Ph.D., is the Raffensperger Professor Emeritus of Humanities at Elizabethtown College (PA) and a Guggenheim recipient. He is the author of numerous articles and 15 books, including, Antifascism: Course of a Crusade (forthcoming), Revisions and Dissents, Fascism: The Career of a Concept, War and Democracy, Leo Strauss and the Conservative Movement in America, Encounters: My Life with Nixon, Marcuse, and Other Friends and Teachers, Conservatism in America: Making Sense of the American Right, The Strange Death of Marxism: The European Left in the New Millennium, Multiculturalism and the Politics of Guilt: Towards A Secular Theocracy, and After Liberalism: Mass Democracy in the Managerial State. Last year he edited an anthology of essays, The Vanishing Tradition, which treats critically the present American conservative movement.

Courtesy Blaue Narzisse. Translated from the German by N. Dass.

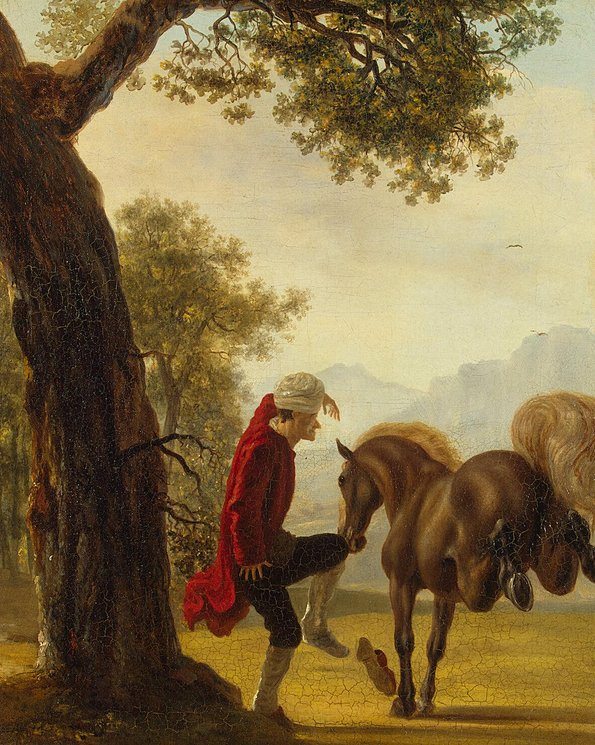

The featured image shows, “Voltaire Taming a Horse” by Jean Huber, painted ca. 1750 – 1775.