We are so very pleased to bring you this interview with Javier Portella, journalist, essayist, writer and publisher, whose recent book, N’y a-t-il qu’un dieu pour nous sauver? (Is There No God to Save Us?) examines the necessity of re-enchantment of the world, from the neo-pagan perspective. We bring this interview through the kind courtesy of Éléments Magazine.

Éléments (É): You published Les esclaves heureux de la liberté (Happy Slaves of Liberty) in French almost ten years ago, a beautiful oxymoron. Tell us about this book? I think it will help us understand the process that led you to write N’y a qu’un dieu pour nous sauver?

Javier Portella (JP): It will help us all the more because my last book is in a way the sequel to Les esclaves heureux de la liberté, which Dominique Venner described, with an overly generous hyperbole, as “a philosophical atomic bomb.” A bomb, insofar as the radical questioning of our time is accompanied by… its praise; by the recognition, more exactly, of its potential virtues. Such a paradox is already contained in the title, which speaks of slaves… free. We have to understand that what makes us slaves is freedom itself, as long as it is not lived in its greatness and adventurousness. What shackles us is the difficulty to stand on the bottomless ground that freedom implies, on the fading of any foundation and very notably of the divine foundation. Insofar as such a fading, such an indeterminacy, is not lived as the risky and joyful adventure that it should be, modern man sees himself tied to (“happy”) chains, where the great mystery that makes the meaning and the beauty of the world, is filled with emptiness and ugliness.

É: The Spanish title of your book is El abismo democrático. There’s no need to translate it, but I would like to ask you to explain it—we didn’t know that democracy hides an abyss. Is it fundamentally hostile to the sacred?

JP: Hostile to the sacred… and to those men who, supposedly free, don’t even see the abyss they have fallen into. They ignore it, because it is covered by the most subtle lie of all: the one that pretends that it is the whole of men who decide their destiny, while these men—these atomized crowds—decide only one thing: to choose every four or five years if they are going to wear a white hat… or a white cap. All the democratic alternatives unfold exclusively within the System, as it is called; within one and the same worldview. If you defend a completely different vision (for example, a vision that is neither materialistic, nor individualistic, nor egalitarian; a vision that advocates the beauty and grandeur of our destiny), you will certainly have the right to defend it; but locked up in the margins, deprived of access to the mainstream media, you will have very little chance of seeing it triumph.

Unless… unless the exception occurs. Because it can happen (very rarely!) that someone appears who, breaking the game, manages to impose a completely different vision of things. May the gods, let’s underline it in passing, have it so for France (and for all of us) next April!

All this is linked to that other dimension of the democratic abyss that you mentioned and which is even more important: hostility to the sacred.

É: Yes, because your subject is not so much religion as the sacred. What difference do you make between the two? What is religion, what is the sacred?

JP: What is the sacred? How can we make men feel it when they have been deprived of it for so long? They swear by the concrete, the tangible, the useful… whereas the sacred—that something that bursts forth in art, nature, the city and the cult of the divine—throws the most intangible in their faces: the ineffable, the wonderful. But perhaps I am going a little quickly. The sacred is not “something,” as I said. It cannot be reduced to this or that. It is like an oscillation, like an incessant coming and going between a presence and an absence, between what we have in hand and what slips from all hands. The sacred impulse (for it is an impulse, a breath, that it is about) offers us everything, but does not let us seize anything. It is elusive. As ineffable as the beauty of nature, which strikes us, says Heidegger, when “the tree in bloom presents itself to us and we present ourselves to it.” The sacred: as ineffable, also, as the other beauty, that of art, which strikes us insofar as it shows everything, reveals everything, at the same time as it veils it by preventing us from supporting ourselves on any founding truth.

For the beauty of art and nature, it is clear; for the enigma of religion too; but why should politics belong, even it, to the sacred? The coronation of the sovereign, as far as I know, has disappeared for a long time; neither magnificence, nor solemnity, nor ritual surround the prince anymore. The emotion that raises the spirit of a people is also gone. The greyest banality, even the most hideous (a wooden language, for example), reigns in the city.

And then? It is the same for the three other domains of the sacred. Nature has become nothing more than a depository from which raw materials and tourist entertainment are extracted. Contemporary “art” is the reign of ugliness and non-art. As for religion, desacralized as it has been for the last fifty years… “The world has become ash-colored,” said Stefan Zweig. But the sacred, however buried it may be, remains no less: in the depths of nature and art. In politics too, where the enigma unfolds between what we are as a people and the impossibility of knowing what makes us be and become such or such, “the unforeseen in history,” as Dominique Venner said, being its key.

É: What specifically about religion? Can a society do without religion as well as other expressions of the sacred? You must agree that this has never happened in history, except in our world. To speak like Alain de Benoist and Thomas Molnar, if this “eclipse of the sacred” persists, can we, as men and as societies, last?

JP: No, it’s obvious. Hence the gravity of the moment. With “the death of God,” as the other said, we have taken all the risks… and we are paying all the consequences. But let’s not fool ourselves. These risks had to be taken—wherever they lead us. And we had no choice. There was no longer any way to continue believing in eternal life, in the foundation of the world by an all-powerful God, in his absolute transcendence, or in his claim to regulate and judge the conduct of men. It was necessary to stop believing, by this very fact, in the effective, not imaginary, reality of the divine, while continuing to believe in its sacred radiance.

But I expressed myself badly (what do you want, one thousand five hundred years of Christian history weigh on our shoulders). The question is not to believe (belief: this intimate act, this personal speculation, which has become the great obsession that Christianity has introduced). The question is not to have faith. The question is to celebrate—whether one has faith or not—the great mystery of the world and of life that the divine expresses; a divine that, recognized as a vital fiction, has no effective intervention—the Epicureans already knew this—in the affairs of mortals.

However, it is the opposite that has been done. Why was this done? Because one could not celebrate, it was believed, a god conceived as a fiction coming from the imaginary. This is to hold the imaginary to be of little value. Notice that such a contempt only concerns the divine imaginary. The same cannot be said of those beings who have emerged from the human imagination and whose names are Antigone, Don Quixote, Faust, Julien Sorel, Bardamu and so many others. Those beings who are more alive than mortals (they never die!); those beings whose deeds and gestures live in us with more intensity than if they had been “real”—without which they would never strike us. In other words, the divine is like art, this theater of shadows and light, this imaginary through the prism of which reality is revealed in its highest truth.

É: But could a god who is openly recognized as imaginary set up something like a cult, like a religion? What do you say to Samuel Beckett when he says: “It is easier to build a temple than to bring down the object of worship?”

JP: I answer that he is wrong; but in a sense he is right. He is wrong, because if the “object of worship”—the sacred, the divine—is not already there, no matter how many temples are built, they will always fail. How else to explain that modernity is the only era incapable of building temples? It certainly raises things that receive such a name. But they are not even temples where one celebrates, as Nietzsche said, “the funeral for the death of God.” What is celebrated in the temple-hangars of our days, vomiting ugliness, ugly on purpose, is a kind of black mass of Ugliness and Bullshit. If the spirit, if the sacred does not impregnate the air of time, the Beautiful—not as an aesthetic refinement: as a shaking—disappears from the temples, from the city and from life.

Becket is quite right if what he means is that the advent of the divine is not ordered. It either happens or it does not happen. Nothing would be more vain than to pretend, by a crazy proclamation of voluntarism, to bring about a god likely to “save us,” it being understood that such a salvation must not be understood in the Christian sense of “redemption of sins,” but in the sense of re-enchantment of the world. And yet, you may say, it is indeed the advent of such a god that Heidegger seeks—and I with him. Certainly. I only say that nobody can know if such a god will come or not. Only Fate, Fatum, that power to which the gods themselves were subject, can decide.

Yet there is something we know, or should know. Such a god—such an expression of the instituting mystery of the being—would know how to arrive only in one condition—that its mythical nature is recognized. What should not prevent that the divine remains wrapped in as many zones of shade or suspension of the judgment as one might want. The instituting mystery of being must always remain mystery. Otherwise, it is being itself which disappears.

Is such a thing possible? Is it possible to recognize and celebrate the poetic-mythical nature of the divine? Or does it imply, on the contrary, a principled impossibility? In the light of our history and our Christian sensibility, it certainly seems impossible. But are there not other historical situations where the divine has presented itself in this way? Doesn’t the history of paganism attest to this? As Alain de Benoist writes, “In paganism, art itself cannot be dissociated from religion. Art is sacred… Not only can the gods be represented, but it is insofar as they can be represented, insofar as men perpetually ensure their representation, that they have a full status of existence” (Comment on peut-on être païen? How Can e Be Pagan?).

The intertwining of men and gods, of art and the divine—here is the key. And intertwining means, the two terms require each other; nothing is first; neither the men nor the gods. To exist, the gods need men who celebrate them and the art that represents them. To exist, men need the gods. This otherness, this sacred without which men would not be anymore.

É: Very well. But, as you say, the emergence of the divine cannot be ordered, nor can the return of paganism be decreed… What is left?

JP: We are left with the only religion that, however shaky it may be, or even degenerate, still stands. I am referring to that Christianity whose followers—today rejected, perhaps tomorrow excommunicated—are, whatever our differences, on the same side of the fence where we stand. In contrast to official Christianity, such as it has developed since the Council and which, far from saving or re-enchanting the world, works for the loss of the world.

Is this something inevitable? I do not know. I only know that once, just once, things have happened quite differently. During the great adventure of the Renaissance, it was not only society that was shaken by its (re)discovery of Antiquity, but also the Church, which, for a good hundred years, between the middle of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, experienced a pagan-Christian syncretism that made possible, among other things, the greatest explosion ever seen in art. This is why I am devoting pages to this syncretism, which seem to me all the more necessary since the matter is surprisingly little known.

What is left of it? Almost nothing, I agree. Nevertheless, it was. And if something has been, there is no impossibility in principle for something similar to happen. Thus, every year in Spain, especially in Andalusia, the processions of Holy Week bring huge crowds (whether they are “believers” or, more surely, “unbelievers”) who are moved, full of fervor, to the passage of Virgins who resemble those goddesses whose name was attached to that of Mary, while that of Jupiter was attached to God the Father and that of Apollo to Christ in the most official texts of the Rome of Alexander VI and other popes of the Renaissance.

It is thin, I admit it. These are only signs; signs—not the proofs—that I was looking for in order to shed some light on the path.

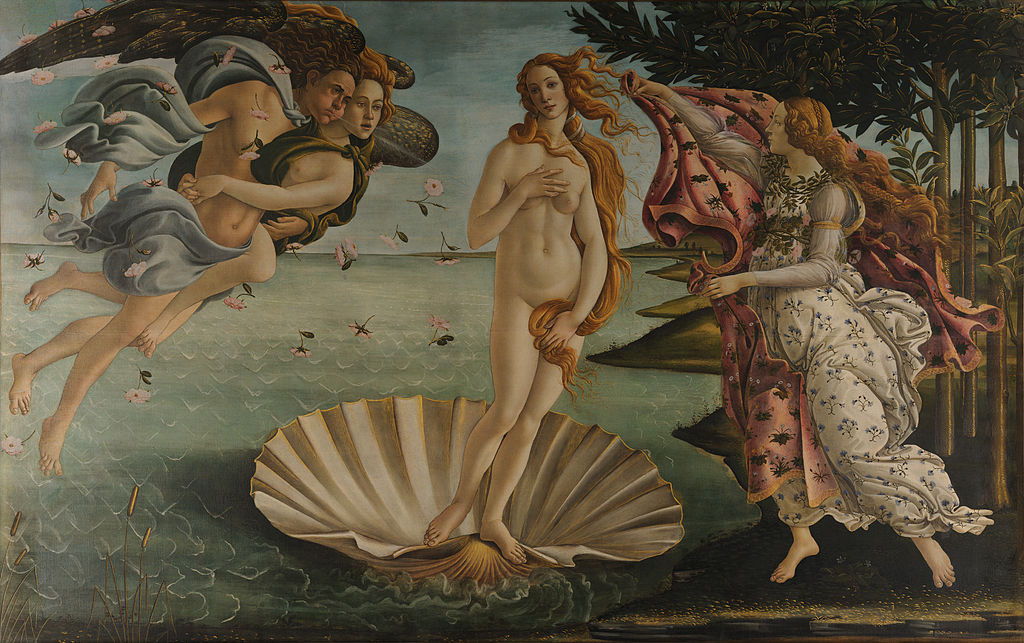

Featured image: “La nascita di Venere” (The Birth of Venus), by Sandro Botticelli, painted ca. 1485.