1.

Three ethicists go into a strip club, with gyrating scantily clad pole-dancers doing all those moves that come straight out of Bada Bing. Sorry, I am joking. It was only two ethicists…

The Kantian, on principle, cannot bring himself to make it through the door—he does not want to view women as merely means and not rational ends. In addition, when he runs through the categorical imperative, he is not convinced that he, a middle-aged portly chap, would like to be out there in his underpants struggling to go up and down the pole. As he pauses to universalize that thought-image of all those other portly comrades falling off poles, he thinks there is no way Kant himself would ever consent to going into the strip club, let alone strip down and climb the pole, even though Kant was skinny.

Once inside, the utilitarian is bent over an iPad, at the bar, trying to collate the relevant variables for the cost-benefits calculation he hopes to make, which include the general pleasure of the exclusively male audience as well as the situation of the pole dancers as wage earners, whether they like or dislike their job, and so on. He wants to interview the girls in their break about the cost/benefits involved, but the club has a strict rule of girls not talking about their work to customers—although, his university ethics committee has approved the survey tucked in his pocket.

The utilitarian also wants to factor in the negative effects on women generally, in this kind of behaviour—though here his calculative compass is a little disorientated, as he is unsure to what extent his female philosophical colleagues are a representative sample of women as such—there are four of them—they are all white (two are atheists, one is a non-religious Jew who is a supporter of BDS, and the other a lesbian Anglican). The female philosophers he knows disagree about pornography, though most are against it, and see the business as unethical. He is not sure whether pole dancing is pornography—and exactly how much it would matter if it were, or if it were more like prostitution and how it would matter if it weren’t.

He also wonders how much pain there might be in it for girlfriends or wives who “discover” their boyfriends/husbands were hanging out in this club, and whether attending the club crossed some moral line that the relationship had established. He starts to think he may need to get his hands on some sociological data about this point. He has decided to build his career upon utilitarianism because he doesn’t like the strict purity of Kantianism and the lack of attention to contingency; and he doesn’t like the elitism of the Aristotelian approach of his colleague, who thinks listening to death metal (which he still occasionally listens to in nostalgic moments), taking recreational drugs (which he is partial to, especially once the death metal is pumped up) and watching shows like Breaking Bad are a waste of one’s talents and communally toxic.

Like the utilitarian, the Aristotelian (who has beefed up Aristotle with some Hegel) finds the Kantian position too unworldly—and dangerous. The most famous Rousseauian, besides Kant, was Robespierre. And, as Hegel had pointed out, the desire to make humanity fit into the principles of virtue Rousseau dreamt up led to heads being treated like cabbages made for the chopping. The Aristotelian finds the whole thing rather sleazy, and the pleasures not really defensible. He, though, recalls Augustine’s and Aquinas’ view of prostitution, while a sin, it should not be outlawed because the city needs a sewer system.

2.

Let’s leave the ethicists wrestling with their problems, their own minds and each other, and ask why does it matter what they think and why would they think it mattered? The most obvious answer is that they think that their opinions about human behaviour are of social importance, and they think that a more rational solution to human decision-making, which impacts upon society at large, is a good thing. Moreover, they think these kinds of problems are reasonable, even if it is not at all obvious what is reasonable about a society in which locations are established for the purpose of scantily clad gyrating women on poles performing for (mainly) men drinking alcohol—though now thanks to some ethical consensus having legal teeth, said men won’t be able to smoke.

There may be some people who run through lines of a carefully considered argument before making a decision about what to do in a difficult situation, such as deciding whether climbing a pole in a seedy bar dressed in underwear and stilettoes is an immoral act. In such cases, the argument itself cannot be divorced from the various elements that have the potential to “trigger” or activate the invariably hidden or “unconscious” powers “making up” the “conscience” of the “inquirer.” Not all elements will trigger all in the same way—there is an inevitable variety of potential weightings that different characters/members of different groups/peoples with their different and innumerable experiences of life bring to the question.

Even, as we suggested above, the way one goes about approaching how to think about “the problem” of to what and to whom one is ultimately loyal is a mystery wrapped in a concatenation of constitutive characteristics of a person, group or people. Character also involves different “filterings”—filtering is the concomitant of consensus, and consensus of some fundamental appeals, is essential to a group’s spirit or character. Different spirits—different filterings, though there is ever a tension in sheer structure of a world-making aspect (recognizing property, providing security and having obligations), which crosses all sorts of different cultures (cultivations of a collective’s preferences, tastes, desires, habits, and potential). And filtering generally involves the interplay of the more stabilizing structural commonalities and diverse cultivations that are as much bound up with diverse contingencies of founding acts and traditions as sheer taste. All of which is to say—it’s complicated. Though the trick with all thinking is to know when to cut through complexity to identify a line or pattern of genuine simplicity, and when to focus upon complexity because the simple is misleading. I confess to thinking that the pole dancers are possibly better at knowing when the complexity is just blather than most philosophers.

We know philosophers love thought experiments, so that they can simplify a complex moral problem—the most famous one in recent decades is the trolley and the fat-man—the brief version: if pushing a fat guy off a bridge will make a trolley veer off the track so that the lives of five people stuck on the track will be spared—but fatty might lose his life: to push, or not to push that is the question? How far we have come since “to be or not be.” Having sat amongst philosophers proudly cogitating over this problem—never bothering to ask who fatso might be (Goering or Churchill?), or who the hapless (or extremely careless) five stuck on the trolley track are (a bunch of serial killers, grannies, university managers, or philosophers?), or what other information would give this silly sketch some resemblance of a genuine moral conundrum—I suspect that a room full of pole dancers would find catering to the desires of their leering sad sack voyeurs to be less an affront to their human dignity than having to listen to such a vacuous discussion.

But there is another issue—the aim of an ethical conclusion is frequently, indeed invariably, to control/transform/improve people through policy and legislation. That is to say it is almost inevitably a political issue; and in the thrust of democratic politics that also generally means a legal issue. Ethics today is invariably “law in waiting.” And there are all sorts of very serious questions to be made about laws that are as deeply ethically conflicted as the discipline of ethics itself—such as what exactly are the boundaries between private vice and public virtue?

The entire ideological conflict between classical liberalism and socialism hangs on this divide. Or, do private virtues always create public virtues? Machiavelli and de Mandeville, in very different ways, raise issues of the sort that should make us hesitate here. Or, what are the cost-benefits to the society of trying to calculate our private vices (presuming there is such a thing) and creating criminal sanctions? Do we just ride rough-shod over these utilitarian considerations because some of us think we have the rational position about the principle, and that the means and the reality, with all its moral quandaries, generated by acting according to the principle, should just be left to another day?

Might it be that the more we use our reason by asking reasonable questions, the more Russian dolls we find. And the more of them we find, the more lost we become through reason. Why should reason either be or lead to good? And if it is good, or always leads to good, is that just a lucky accident, or does that suggest a quasi-classical view of life as literally mind-full? Yet of one thing we can be sure; social problems demand solutions: in a democracy the matter of which ones has to do with their being raised. Which again is a political process.

Of the three positions I took as typifying ethical schools, there are, at least in their origins, somewhat different political connections involved. In the case of the Aristotelian, The Ethics was not conceived as a self-contained work, but as a work examining the kind of conduct required for someone to enter into political life, which was why Aristotle paired it with The Politics. The Politics, though, also took into account forms of political life which were far from healthy; and it considers how to make them more healthy, if not outright good.

Aristotle’s version of the natural supported the moderation (allowing for his historical context) that runs through his work. The idea that our judgment about the ethical should be completely free of any natural influence (i.e., Kant’s position) would, I think, have struck both Plato and Aristotle as absurd, though Aristotle might have seen it as an unfortunate residue coming from Plato’s two worlds. But then again, the Rousseauian idea that freedom consists in having a law which we give ourselves would have repelled Plato as much as Aristotle. And on top of this, both would have scratched their head about why freedom was now the axis of the ethical life. And the accompanying emphasis upon human dignity would have been just as perplexing—especially when it was simply extended to all by virtue of an act which required no action on the part of the person possessing it, viz., that person’s humanity.

The cleavage between classical and modern Enlightenment ethics, not surprisingly, is closely associated with the cleavage between the classical and modern, more specifically the Enlightenment, view of politics. And just as Aristotle is interested in identifying those qualities—the ethics—which need to be exhibited in the person entering into the political sphere of life, the enlightened modern principles of the moral life are also intended to act as the constitutional basis of a legitimate (hence rational) political formation. The reasoning, in Kant, is that the purely reasonable moral principles must be unsullied by any extra-rational condition (motive, desire, feeling etc.) which provide the pure disinterested ground for adjudicating on social harmony.

Rousseau, on the other hand, both emphasizes the natural character of empathy and the need for virtue to detach itself from the forces of selfishness that we are prone to as creatures conditioned by the laws and nature of civilization.

Kant is the more consistent metaphysician, and hence his greater reputation as a philosopher. But this is matched by Rousseau having the greater reputation as a political theorist. His theory of the general will, though, is also both the model and impetus for Kant’s categorical imperative, and the political endgame of the moral imperative. Kant was rigorously consistent in conceding that none could ever know if someone really acted out of a moral principle (the Kantian who didn’t go into the strip club may really have been worried at some deep level about how his partner or other philosophers back at the office would view him, if they found out). But such a concession does nothing to alleviate the common objection to Rousseau: that the general will requires that each of us leave aside our particular or vested interests, which is far easier said than done because most of us are oblivious to exactly what our interest involves.

The fact that academics, including moral philosophers, and students at the most prestigious universities in the Western world think that they know how to achieve the public good, and that we should obey them as they receive their salaries or prepare for lucrative careers is indicative of how much self-serving-ness is behind the idea of social justice and the public good today. Likewise, the Rousseau problem is that the kind of society he helped facilitate—a society in which ideas about the general will abound—has created a slew of people employed publicly and privately to identify, articulate, and implement “the general will”—along with the academics, the bureaucrats, journalists, teachers and politicians, and lawyers, and, perhaps most incredulously, actors and entertainers.

And, sorry to have to break it to you Jean-Jacques, such people cannot but help inject the very self-interest that the principle is designed to eliminate. They invariably design, enforce, and monitor policies, rules, narrative laws, etc., which shore up their entitlement. It’s a perfect circle of elite power formation in which the kind of legitimation that had evolved out of the need to survive and protect the group is replaced by a group whose power is built upon ideas and words. No wonder they wish to stop the spread of mis-information, which happens to be any information that does not receive their imprimatur. This should be obvious; and it is obvious to those who are either not part of that elite, or who wake up from their slumber and look at what a political mess this elite is making.

The Rousseauian/Kantian constitutionalist approach to the political also provides the philosophical grounding and rationale of institutions, such as the European Union, and UN. And the criticisms levelled at these institutions are also but variations of the critique just mentioned. The hiatus between institutional reality as a conglomerate of practices and practitioners and the ideal it is supposed to represent or express is indicative of a dualism that I think is inescapable—when we reference reality to an idea.

Even in instances where there is an acceptance that deontology of the Kantian sort is too stringent, contemporary ethical philosophy invariably devotes itself to mapping out what is rationally right and thus laying down what we ought to do—thus assuming that (a) we don’t really know what is right or wrong unless we receive philosophical guidance; and (b) that the philosopher has the right tool—reason—which he or she or they (pronouns themselves now being considerate philosophically serious matters) can wield well. This is as true today of Aristotelians as it is of utilitarians, though the problem I was alluding to above about utilitarianism lies in the open infinitude of its variables—and the most plausible way of solving the problem was to dissolve utilitarianism into economics. Of course, by dissolving worth into monetary value, utilitarianism risked losing connection with the sentiments which find expression in Aristotelian or Kantian types of ethics—but at least it was able to come up with a cost-benefit calculus that worked. However, while developments in economics were driven by utilitarianism (obvious in the most elementary premise of much modern economics, marginal utility theory), not many utilitarian philosophers would agree that the ethical problems they wrestle with should be left to the marketplace.

Generally, ethicists defer (most do so tacitly) to another branch of philosophy to decide exactly what reason is. But while that shifts one problem to the side, the other problem remains insurmountable—the ethicists have a very tough job getting other ethicists to agree with them.

But the fact that there is no one ethical theory which philosophers find universally convincing does not perturb the many philosophers who press on in the hope that they will or have found the proper principle and/or theoretical approach. The fact that they keep searching, after some two and half thousand years, might lead us to think there is no definitive answer waiting in reason’s cupboard.

Indeed, as philosophers keep searching, as problems spawn diverse groups of adherents, and as each more innovative philosopher stands alone with his/her/their own philosophy, we need to ask what is really going on here. One thing is definitely going on—”ethics” is a discipline of a profession called Philosophy, and to be a member of this profession requires that one keep “researching” and writing on one’s topic. So, there is definitely what Marxists call a “material” interest that keeps the debate going. There is also the question of what exactly is not only a philosophical argument, but a convincing philosophical argument about ethics? Would it have to—indeed, could it—convince everyone, for it to be seen as a definitive example of a convincing argument? In the case of the physical sciences, we have sufficient consensus of proof structures, and methodological procedures, so that practitioners of the discipline can generally share a common disposition toward the “evidence” at hand—but this is not the case in philosophy. And if it is not the case in philosophy, matters get no more “reasonable” the further we go outside the academy and into the world.

3.

Why then are we taking ethics seriously? In part it is because we take reason, understood as rational argument, as a means of orientation seriously. But philosophy has long disputed about whether our moral institutions may be a better guide than our reasons, or whether reason can be completely detached from our moral intuitions. Some philosophers like Hume, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche thus intertwine reason and intuition as simply intrinsic to action. So, as Schopenhauer puts it, willing and representing the world we participate in are part of the same process; or as Nietzsche puts it in Beyond Good and Evil (not without some unconvincing rendering of how he differs from Schopenhauer) “a genuine psycho-physiology” sees “thinking as only the relationship of these drives to one another.” Hence, from this perspective, to draw a sharp distinction between intuition (moral or otherwise) and reasoning is already to be subject to a philosophical prejudice. Thus also Nietzsche’s one page History of Philosophy in the Twilight of the Idols—”How the ‘True World’ Finally Became a Fable”—is “The History of an Error;” thus also the opening chapter of Beyond Good and Evil is entitled “On the Prejudices of Philosophers.”

Nietzsche embroiled himself in a great deal of pseudo-physiology (typically played down in post-Nazi/post-fascist readings of Nietzsche). And a major flaw in his thinking was that he was too prone to replicate the mechanistic metaphysicians with their distinction between primary and secondary qualities, instead of sticking to his own advice about staying with appearances—for the social world is so symbolically saturated. While it does not change the fact that we laugh and cry, bleed and die, it does mean that an enormous amount of what triggers responses in us that make us weep, laugh, harm or seek redress is due to social codes, roles, manners, and expectations, as well as economic and technological modes and processes.

One of the great downsides of the triumph of philosophical naturalism (somewhat countered in different ways by Marx, Nietzsche, and more especially Husserl and Heidegger) was that what had evolved as a metaphysic to deal with the specific problem of the interrogation and manipulation of nature, to serve human desires became served up as an answer to everything. To be sure, post-Marxist and post-Nietzschean (and hence post-structuralist) philosophers focus primarily upon the social character of Philosophy, a great deal of Philosophy carries on oblivious to the significance of sociality. This is evident as much in its grammatical undertow of the indicative and subjunctive moods, which facilitates the philosophical task of showing what the world is, what is wrong with it and how it can be fixed, as it is in what, at different times, commands its attentions.

The philosopher working on an ethical problem sees his activity as purposeful in itself, and the history of the practice of no more importance than the history of medicine to a doctor. Except medicine is an empirical science. The classical approach to ethics in both Aristotle and Plato is akin to this medical model. But while there are very powerful aspects to the classical approach; there are some equally powerful counter-considerations and hence criticisms. For example, the classical approach to the good is that it tries to harmonise what exists, even if it does so in the idealist manner of Plato in the Republic (assuming for the sake of this argument at least that Plato genuinely believes in the model he builds). But this means the good becomes an obstacle to the better.

I would not argue for a moment that the history of Western civilization has been one of constant and uniform progress; but I doubt that anyone who wished to return us to relationships of fealty, or take voting rights away from women or working-class men would be thought to be defending a position that would garner much consensus. But while I think what I have said is true of people whose lives involve all manner of investments and whose identity is staked around these boons of freedom—i.e., us—there are plenty of spokesmen for a restoration/creation of a pre-liberal society, such as advocated by members of the Taliban, ISIS, Hizb ut-Tahrir, who appeal to social possibilities and actualities which have appeal for them.

Some years ago, when I spent a lot of time watching, for example, the British Islamist Anjem Choudary attack modern British society and its freedom, while defending the virtues of past and future imagined caliphates and the social and political strictures and directives which he finds in the Koran and hadiths, it was very obvious that, though I thought him mad and bad, he was no less capable of drawing inferences or mounting arguments than anyone else. He and those sharing his “idea” of what human qualities, practices and institutions are really “good” and “true” and “beautiful” can easily be dismissed as mad and bad—but what good exactly do such classifications serve? He and those like him who speak and think and argue in similar ways, find audiences, convince others, who had previously never had any interest in the kind of appeals Choudary and Co. were making to the form of life they advocate.

4.

My discussion of philosophy and ethics has proceeded largely in keeping with the kinds of positions typically laid out by philosophy departments in the US, Canada, UK and Australia; that is, by departments that have come out of the Analytical tradition. But if I were to shift for a moment to connect the point I have just made about the collective rationalisation of, and commitment to, contingent values to the manner in idea-brokers, professionally invested in defining the specifics of the general will I mentioned above, then I think we can better see the kind of terrible paradox plaguing modern ethical thinking. That is, on the one hand it has sought to replace revealed truth with reason—and let us add that life itself is a revelatory process, and one great mode of revelation is the revelation of what kind of creature we are due to our very instincts (instincts themselves being “micro-reasoning” processes that we respond to), only to be confronted with the absolute failure to find any kind of compelling consensus that even those who defer to, and make a living out of, using their reason cannot achieve.

On the other hand, if we shift away from analytic philosophy but turn to the kind of philosophically driven hegemonic narrative that now passes for truth amongst the Western elite wishing to dictate how we should all behave, we see a certain confirmation of Hegel’s idea that reason is totalising and substantiating. Let me add immediately that I think Hegel is only right to the extent that what he calls “reason” is defective—defective by virtue of making itself primary when life teaches us again and again that reason is not primary. God is not reason writ large, and neither are human beings reason writ small.

But Hegel’s argument that reason is substantive, that it is dynamic and historically and socially saturated and not just an empty set of cognitive procedures, which we deploy to fathom experience or form extra-experiential claims about the morally good or the beautiful, strikes me as having trumped the position, still on view every time one witnesses analytical philosophers discussing ethics. If we accept this, then we will also apply Hegel’s critique of Kant’s moral theory to all variants of “principle”-style ethics, viz., the contingency has to be fathomed in light of its sociality and historicity; and this includes the contingencies which constitute our very selves.

The modern propensity to take seriously moral abstractions as political absolutes invariably contribute to a class of people who no longer seek the classical objectives of reason’s quest—the good, the true and the beautiful—they have become the instantiation of the good, the true and the beautiful. That’s where the entertainers come in—they ensure the good and true are not left hanging in the air, as they tie (ostensibly) rational moral commands and proscriptions to flesh, blood, desire—though, because they earn their living by pretending to be who they are not, they are also intrinsic to a world of image presiding over the real. That is, they represent the representations that the creators of value have laid out as pertaining to the public good—which is emancipation. This why they are as much an embodiment of Nietzsche’s higher men and women, as they are an expression of Plato’s philosopher kings, as of Kant’s instigators of the moral imperative, as the legislators of Rousseau’s general will. They are also the harbingers of Marx’s unalienated society and their further honing of who is oppressor and who is oppressed is predicated upon his primal model of class antagonism.

What we see here, and what I will continue to extrapolate upon, is a process of modern reason’s substantiation—a substantiation which reconciles vast contradictions, and which, in spite of the fact that our lives are built around contingency and encountering which defies any kind of Hegelian totalism, the philosophical contrivances, devoted to emancipating us, is an astonishing confirmation of Hegel’s principle of the dialectical development of identity within difference. For the spirit of our times conjoins philosophies that on the surface should be completely antithetical to each other, but which become variations of the one spirit of our own time. The great reconciliation, that is also a time of the great emancipation, was, in the formulation of Derrida and Agamben, “the to come.” It is both an intimation of the messianic and an instantiation of the true, good, and beautiful, as all the victims of the earth now finding their voice, thanks to our cultural moral/ethical leaders. It is Lenin and Lennon—“What is to be Done?” plus “Imagine” as ethical life. Everything important has become ethics, and the antinomian-ism of the ‘68 generation (the story has been well told in Julian Bourg’s From Revolution to Ethics: May 1968 and Contemporary French Thought) was just the vehicle by means of which jouissance/play/desire, etc. all became the ethical emancipatory key.

I have jumped into the way in which I think philosophy has provided a kind of unified consensus within a certain group—it is as I have also said a very Hegelian development—the fact that those making it frequently despise Hegel (Deleuze, for example, and Foucault) is completely beside the point, in so far as they were so caught up in their faith in their own ability and game that they were very poor judges of what they could be seen as doing by someone who was not interested in joining in their particular associations and priorities.

The above observation illustrates (even if we have not had to completely buy into the entirety of his system) the truth of Hegel’s argument that reason is substantive; that it is dynamic and historically and socially saturated and not just an empty set of cognitive procedures, which we deploy to fathom experience or form extra-experiential claims about the morally good or the beautiful. It also strikes me as having trumped the position still on view every time one witnesses analytical philosophers discuss ethics. If we accept this, then we will also apply Hegel’s critique of Kant’s moral theory to all variants of “principle” (style ethics), viz., the contingency has to be fathomed in light of its sociality and historicity; and this includes the contingencies which constitute our very selves, and the ethico-socio-political priorities of our age.

5.

This leaves us with the conclusion that our world is our world, and the reasons (in the sense of arguments, and not simply inferences) we have about it are stories we tell ourselves to console ourselves about it or help us change it. Ethics is but a particular means of making a story, to try and get people to act in one way rather than another. If we notice the philosophical stories which emerge in an age and which are responses to the problems of the time, by a group whose ways and means are very similar, we can see that their differences are not that different. Or rather, to become seriously different they have to step outside of the ideational consensuses that are intrinsic to the philosophical game they are involved in.

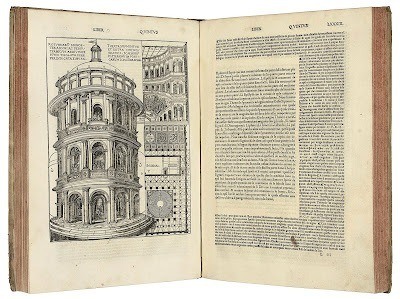

Thus, to ask why this particular “game” (the game of philosophy as such, and, more specifically, philosophical ethics, is being played is not irrelevant), it gives us pause to think about the game we (ethicists) are playing; why it commenced. For the hopes latent within it are very conspicuous in the origin: the classical ethical reasoning of Socrates and Plato. It is closely bound up with a need to legitimate itself—to differentiate philosophical reasoning from alternative types of pedagogical (which Plato represented as pseudo-pedagogical) speech, viz., poetic/sophistic/and oratorical speech. Plato saw these forms of speech as suffering from the same methodological deficiency, viz., lack of illumination from ideas, which have been espied by recourse to properly breaking down the one into its many parts and rationally reassembling them into a rational definition. Aristotle was a Platonist in so many ways, but he could not come at the theory of ideas. Yet he too hoped philosophy would solve the problem.

To repeat and develop my earlier point, if a philosopher ever solved the problem of the best or most rational way to live, he or she was no better at convincing other philosophers than our professionals today. Ancient philosophy proliferated with competing schools and doctrinaires, whose members Lucian depicted (apart from his sceptical-minded, robustly “common sense” position) in the second century, as nothing but a scrubby rabble, full of self-importance, spouting nonsense.

Indeed, there is quite a serious comic critique of philosophy running from Aristophanes’s Clouds to Lucian’s Hermotimus or the Rival Philosophers to Rabelais’s Gargantua and Pantagruel. It is interesting how closely it parallels the religious criticisms of philosophy that run from Tertullian, Tatian, to Pascal and Kierkegaard—for both critiques draw attention to how little we know, and how little reason itself helps us with the most pressing decisions that befall us: how at sea we really are. The comedian has us laugh at the absurdities of who and what we are, and frequently has us laugh at the pomposity of authority (or those who want to usurp it)—and how delusional we often are. The great religious thinkers also emphasize the absurd, but in connection with the miraculous-ness of creation transcendence and/or redemption.

But if philosophy can be criticised for not delivering on its promise, this does not mean that philosophy does not produce its “offspring,” does not have a legacy. Of course, it has. In the case of classical philosophy, its legacy is visible in the Roman Empire, in the works of grammarians and legal thinking. But where philosophy started to garner real power was not in the ancient world. In antiquity, it was not philosophy that pulled antiquity out of doctrinal and political conflicts, or forged a greater social or political unity that we might well call more ethical. Antiquity was changed far more by religion than philosophy. The solidarity of the underclasses throughout the Roman Empire was largely achieved socially by Christianity.

I would also venture that philosophy would have died out were it not for religion—Christian and Moslem scholars who were able to revive philosophy in a social world of tribes and imperial growth. There is, to put it bluntly, nothing natural about philosophy—even if the concept “nature” is a term favoured by classical philosophers. It is an exotic plant, which is the result of a plethora of highly unusual socio-political (there is nothing, as far as I can see quite like the polis in antiquity) and narrative innovation and conditions (the importance of poetry, the particular abstractions it generates, the discord within the Greek pantheon, most painfully expressed by Hesiod in the Theogony, underpins a search for a cosmic moral order).

Moreover, while nothing might seem to make more sense than the History of Philosophy as the story of a self-contained development of a practice beginning with the Pre-Socratics, moving through Classical Greece, Rome and the Middle Ages and then Modernity and the situation now. Yet what philosophy meant for the Epicureans, Stoics, neo-Platonists, the Scholastics, or the mechanistic metaphysicians, thinking about the universe as an object of scientific inquiry, is due to all manner of non-philosophical contingencies, especially historical circumstance and location.

The value of applying philosophy to contradictory legal and theological points, for example, was crucial in the introduction of Aristotle into Western universities; but that was predicated upon a proliferation of legal domains requiring some kind of systemic legal reasoning—while the Thirty Years War (and its English compatriot the Civil War), was pivotal in the emergence of Deism and the mechanistic metaphysical view of life that broke with all the mess of history, and that embroiled such geniuses as Descartes, Spinoza, Hobbes, Locke, and Leibniz. This does not mean that truth is reducible to the contingency of an origin, but philosophical truths are inescapably anchored not just to reality as such, but to the contingencies of communal life. And communal life is located not only in nature’s world, but the world of human nature—which is the world of nature as well as beyond nature: symbols and history.

The human world is as much a world of imagination, of taking nature and remaking it, including our own nature and our own growth. This is not a relativistic metaphysical claim, but an empirical one: for as we try to make the world one way rather than another, we focus upon features of our story which were invariably hidden from those looking in another direction. We are ever making ourselves and our world, and that making is formed by the surging and convulsions of living pasts incubating in the plethora of inheritances which we wake up to everyday, buried as they are in our language, our institutions and social choices and values, and the contemporary reactions to what appeals to or disgusts us, what we fight for or flee from, and the alternative futures which beckon or attract us.

In making our future, we invariably remake our past, the remaking of which also impacts upon how we remake our future. This relationship between past and future is further complicated by the crises and catastrophes which take place in the present, which makes us rethink our future and thus also our past, and so on. This temporal triadic interflow renders meaningless any idea of us being disinterested subjects (except on “special occasions,” as a methodological “moment”), or there being some mere object to be observed. What disinterest we may garner—as a member of a jury, or the observer of an experiment—makes sense only once we have portioned off a bit of life that matters for us. We cannot get completely out of our own way. We are always making ourselves in our own ways; we are our ways. But our own collective life-ways differ radically from each other precisely because different collective dreams, traumas and memories are not simply capable of being overlaid upon each other. This is also why to simply interrogate such conundrums in terms of ethical absolutes or relativism is to surreptitiously transform an anthropological condition into a metaphysical problem. No wonder the problem is insoluble.

The different trajectories and prejectives of different collectives have been described by Rosenstock-Huessy as being a problem of different time bodies. For living groups are entwined in their own temporal cadences: which is why suddenly bringing groups together who have no common sense of mourning or triumph is so fraught with problems. It literally takes time to make a new time together. Another way we can say this is that the social imagination is also intrinsically temporal. For our imagination is social to the extent it dwells on what we share or should share, and it is fuelled by regrets, fears, and pride in the past, and/or present, and/or future. It holds out promises so that we can have a tomorrow worth living or fighting for. This process effects all of us; but it makes no sense to render it as a process in which there are objective truths about us and the world that we must locate before we act. We live on the brink of trial and error. But our trials and errors, to repeat, are not ones that are simply conglomerates of facticity.

The fact is that we moderns, who do philosophy, share a certain common sense because we share a world. If we enter sympathetically into another world, as anthropologists do, we can see what matters and what makes sense in those worlds. And those terms “matters” and “sense” are apposite words pointing to a collective pre-philosophical understanding of collective life. To say “something matters” is to recognize that it materializes. To say it “makes sense” is to say it is sensory-forming, as well as meaning-forming. The making-sense of a world, or making things matter within the world, is a social process of mutual participation, a sharing of collective emotional and mental depth. It is a dialogical process involving shared filtering. To be sure this filtering and selection may happen in diverse ways—common opinion, or victors’ stamping and sealing events with their narratives. But even in such a case as the latter, it remains real only to the extent it is formative; and if a people cease to conform to a particular cluster of narratives, they will rethink their past and future. And they do not need to await the declamations of a philosopher masticating on an old saw to see what really matters in their lives.

Philosophy is but one means of making “such stuff.” Within modern times, it is astonishing at how much “stuff” can be traced to philosophy: without philosophy there would have been no scientific revolution, nor modern politics as we know it—for all the ideologies of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries are incubating in the French Revolution—a revolution which was in its inception identified as a revolution of “philosophism.”

I do not mean to suggest that modernity is only built out of modern philosophy—that is not true. The combination of commercial revolution and a republic of civic virtue, which lays the grounds for liberalism, antecedes the ideas of the new metaphysicians and has its roots in theology, specifically Calvinism. Indeed, just as Medieval philosophy was nurtured within the bosom of a faith, the anticlerical philosophes of the Enlightenment are the progeny of Calvinism and monarchical and religious intransigence: the blood of the Huguenots, the animosity towards the Jesuits, the failure of the Catholic Church to reform, and the role of servitude the Church played alongside the nobility in walling off the crown from Paris and the country side. All these processes, and many more, conspired to transform what had become a class, the intellectual, into political actors seeking to make the state in their image.

Plato hoped that philosopher kings would save the polis, but it was the French philosophes who succeeded in enflaming the crowds and political actors who would wipe out the non-enlightened and thus illegitimate modalities of power which had been the bulwark of the European state. The French Declaration of the Rights of Man pays direct tribute to both Rousseau (it references the general will) and Montesquieu (it references the separation of powers).

But the French revolution more generally spawned faith in genius taking precedence over authority, in the rights of people to will their own future, unencumbered by the dead weight of traditions. Rights, reason, and national will seemed to effortlessly flow into each other, as if nothing were more obvious than our being able to publicly judge the worth of all authority and right. That the twentieth century would entwine these ideas into the most hostile and contradictory and ideological strands was not anything any eighteenth century philosophe seems to have envisaged. Yet surely socialism and communism were philosophical products, attracting all sorts of philosophical minds (Plekhanov, Bukharin, Korsch, Adorno, Benjamin, Bloch, Lukács, Althusser, Negri—to just take a small sample). While Fascism and National Socialism were anti-intellectual in all manner of way, nevertheless, they still managed to attract some of the greatest philosophers of Italy (Giovanni Gentile) and Germany (Heidegger and Carl Schmitt). The three ethicists and the philosophical dispute we considered at the beginning of this essay all look rather innocuous when compared to the more bloody philosophical contestations of modernity.

But philosophers have been no better at settling their political differences than their ethical differences. Possibly the only thing philosophers agree upon is that philosophy is a worthwhile activity, and that a society is better with it than without it. Though it is not only the conclusions that separate philosophers, it is even an agreement about what it is. The mainstream consensus, somewhat felicitously, concurs that there is but one major divide on this issue: that between Anglo/American-Analytics and Continentals. In the eyes of the majority of Anglo-American professional philosophers, one of them is rubbish the other philosophy. But this is a professional squabble. In fact, and to pick up an earlier point, faith in a method enabling us to be, as Descartes put it, “lords and masters over nature” so that we could live more comfortable lives (the objective of Descartes’ philosophy) has been tremendously successful (though if happiness as a variable is factored in as a criterion of success, its value plummets). Likewise, faith in the science of economics, which grew out of moral philosophy.

One feature of the metaphysicians of the scientific revolution, rarely given enough attention, is that it was predicated on the need to bring the imagination under the reign of the understanding—thus the importance of the facultative logic which is operative in Descartes, Locke, Spinoza, Leibniz, and which culminates in Kant’s three Critiques.

But it was precisely because of the dangers of demanding and expecting too much of nature’s laws that moral dualism of the Kantian sort emerged as a reaction to the Spinozian and Leibnizian equation of freedom and necessity. Likewise, it was the recognition that humanity spiritually needed to do more than just know the world around it and try and act with dignity that led to aesthetics (a philosophical branch completely absent amongst the early mechanistic metaphysicians), becoming an important field of modern philosophical inquiry. Schelling and Hegel—on the continent at least—and Schopenhauer pushed these three great bastions of the true, good and the beautiful into previously unheralded territory—and after Nietzsche, they no longer made any sense. (Though the Anglo-American Analytic has remained far more tied to the metaphysics of the seventeenth century than the Continentals have.)

I want now to return to the contingencies which we put under the rubric of religion. For in the Western world, religion has largely been relegated to the domain of private belief, which is able to be expressed publicly only within certain sites allocated by the state. In this respect, the Enlightenment has triumphed over Calvinism, philosophy over faith. It is also because of this triumph that ethics takes on such importance—because we need orientation and, at least, within the public sphere, we need to compensate for the fact that the more “enlightened” we have become, the more disconnected we have become from each other culturally, socially, and spiritually. Philosophy would like to heal our fractured and fragmented world, but I fail to see how it can do so—for it is predicated upon a plethora of talents and conditions being met, which are held by few and of little interest to many. Not only that, philosophy as a discipline in itself the way it is practiced is but one further symptom of our fractured world. So too is the notion that there is something called religion as opposed to the “what is not religion.” The moment philosophy dictates what the gods should be (Hesiod, Xenophanes and Plato), the gods have already begun their flight. While Plato and Aristotle imbued the universe itself with a certain rational and moral purposefulness, the focus of the moderns is upon the motion of mechanisms, which means divesting all moral authority out of the universe—leaving it reside purely within the human subject via our communal sentiments and habits (Hume), will (Kant), history (Hegel), will to power (Nietzsche).

Everywhere we turn prior to philosophy, we see peoples who imagine the world/ universe as spirited or god-ed in some way. God/s, humans, world are the poles of the real which humans have traditionally addressed and confronted. The philosophical disposition asked after the nature and essence of a thing; but pre-philosophical humans supplicate themselves to, call upon, or summon traditional powers in order to carry out their lives. Most importantly, the kind of powers they are is not revealed through “observation” but through the kind of life one has. To the philosophical mind this is not satisfactory because it could be false: but what does it mean to say that a life is false? Are indigenous lives false? Hindu lives false? Does a false life not bleed and cry and laugh as much as a “true” life? To those who reply, but it is only the beliefs that are false— I reply but are we not already introducing a certain kind of fracturing technique when we look at gods as objects of “belief,” as if their existence was something that could be divorced from the kind of worlds in which certain names, rituals, practices and routines that sustained them and are sustained by them are made?.

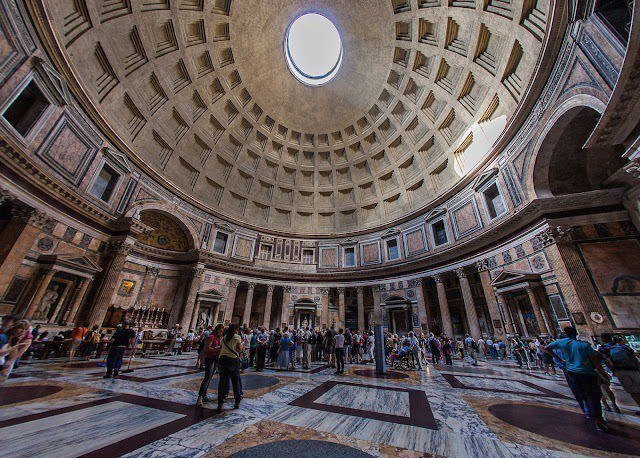

The great problem with philosophical notions of truth as involving some kind of correspondence between intuition and concept (to put it in Kantian terms) is that the intuition we are asked to consider is itself a fiction. For we are asked to consider a living power as if it were a spatial and temporal power subject to a certain kind of reductive compositional analysis. But one has to accept already that spatial temporal powers and the kind of modelling accompanying them are the only powers that are real. Or else, if we wish to stay with Kant, they are either generated by reason alone or else fevered imaginations; that is, imaginings not curbed by the understanding which has slowly built itself up piece-by-piece with confirmable representations. And yet there is a Chartres Cathedral, there are pyramids and ziggurats, temples, frescos of Jupiter, prayers and curses to gods—a panoply of lived god-ed worlds, each revealing meaningful lives.

We might not see the world in the same way anymore, and while we might find all manner of aspects to them morally objectionable, they are not a whit less ontologically loaded than our world, with its own plethora of technologies, techniques and superstitions (does anyone—outside the beneficiaries of the discourse—not consider managerialism a superstition?).

A world is shot through with imagination, and the imagination is triggered by all manner of powers—emotions and traditions, panics and hopes, alternative futures. Our understanding is an important disposition that we may bring to bear upon our imagination; but it is a matter of faith whether it is better to trust it than our imagination. For our imagination may yield all manner of fruits that exceed our understanding. To be sure, if claims about processes are made which are clearly capable of a reductive analysis, then a true analysis may well occur—though even this is tricky. For what we are doing and what we think we are doing do not always match up. On the other hand, the world is full of shysters and rogues; but along with deluders are the self-deluded. The real test of a claim is frequently not to be found, though, in the terms in which it is made, but in the contribution to a certain kind of world which it makes.

Our world is not (as late Wittgenstein appreciated as well as anyone and which he used to overturn his earlier philosophy) a stock of items, a collection of facts which are all that are—we are facting and defacting constantly, imposing ourselves with our half-baked grasp of things and fully fledged confidence in what we want and believe. It is only some facets of the real that we may know, even with open-mindedness. On the other hand, there is no shortage of people and peoples who world themselves via their faith in magic of one sort or another—many have their livelihoods, much like the bureaucratic, political and legal spokesmen of the “general will,” implicated in the magical view of life they peddle. Where clear lines can be carved between “objects” and “subjects,” all well and good, then a certain philosophical disposition may comfortably affirm the importance of its existence.

But the economics, anthropological and sociological and political dimensions of any life-world implicate even the most dispassionate and empirically verifiable truths. The traditional way philosophy has tried to shore up its “understanding” of a more reasonable way to view reality is to break up reality into a plethora of potentially certifiable claims (again Descartes strikes me as the master puppeteer here). But I repeat it is one thing to sharply bring into question through naturalistic sound philosophical means the belief about the way the world is, and another thing altogether to question the persons who are making themselves and their world through their fantasy.

And this is where, like it or not, we all are bound together. There is no escaping the fantastical nature, not only of our existence, but of the meanings we give to our existence. Nowhere is this more obvious than in historical memory. While it is one thing to be able to argue that events, such as Caesar crossing the Rubicon, Columbus reaching America (even though, after three voyages, he died thinking he had reached the Indies), Bradman getting a duck in his last innings confirm that truth is not merely relative, there is no event of any real significance which does not contain such a massive array of interwoven processes (causes), aspects, and consequences that anyone who invokes reference to the event in making the case for others to join him or her in acting a certain way can avoid filling-in all manner of gaps.

We cannot face the future in any plausible way without reference to our understanding of the present which is itself saturated with historicity—and everybody’s historical memory is but bricolage and shard. All memory is episodic—and the episodic is always of bits and pieces. There was momentous irony in the fact that the general tendency to ahistoricism of the Enlightenment precipitated the Romantic reaction which led to historicism—but historicism rested upon the fanciful notion that the historian’s own interest in history had nothing to do with the historical facts being “discovered.”

We dwell in shadows and dreams as much in light. We are as moved by cries and sighs, roars and whispers as by reasons; and reasons themselves being inseparable from sociality and historicity are also “results” of cries and sighs, roars and whispers. We are a plethora of possibilities and powers that may be activated in countless ways and by all manner of invocations and declarations—will we really be better off if we curtail all these, so they conform to a certain modality of speech? Ultimately this is what philosophy is—a certain kind of speech, a cluster of grammatical proclivities and accentuations which open up some vistas of the real, but at the expense of others.

Being “at the expense of others” is part of the very raison d’être of philosophy—Plato’s fury at poetry for its implication in Socrates’ death is fortunately quickly recognized by Aristotle to be overstatement, and he more sensibly and generously concedes the importance of the poetic in our lives. The Platonic expulsion of poetry is echoed some two millennium later in the Enlightenment critique of religion.

The Enlightenment arc that runs from Descartes, through the French revolution and Napoleon’s “liberation” of nations from empire, then the subsequent waves of national liberations in the 19th century would flow into a century of World Wars that had much to do with philosophical faiths, particularly the faith in the political form that had been so strongly advocated by the philosophes—the nation. Kant’s contemporaries, in different ways, J.G. Hamann and Friedrich Jacobi both emphasized that faith penetrates our being so much that it cannot be ontologically severed; and Heidegger, though somewhat more coy about his theological debts, was doing something similar by trying to disclose the fundamental ontological disposition of Dasein.

But we do not need philosophy to tell us that the world that we live in is a vast entanglement of orientations and faithed ways of existence. Charles Taylor’s (and not only his) formulation of the “Post-Secular,” to describe the kind of world we in the West now inhabit, catches the reality that the secular mind-set is but one; and whether it is the most rational or not does not really amount to anything—for the whole question of what is reasonable means nothing, if it does not put reason back into the life-worlds of those who use reasons. Indeed, that is the issue that breaks the enlightenment hold—whether reason is something which is part of what we do, or whether we are part of reason. After Nietzsche, it is difficult for anyone to accept the metaphysical God of Reason. Yet, our so-called godless state has re-opened the matter of religion in the most interesting of ways.

I mentioned above the faiths behind the World Wars; and that raises a fundamental question of philosophical-anthropology which is all too often ignored because of the fairly ubiquitous acceptance within philosophical circles of the myth of the “free” self. Again, as with Nietzsche, the “self” is as much a myth as the sense of freedom, when it is transported from being a relatively useful way of expressing a certain narrative sense of identity (which not all human beings—babies, people with Alzheimer’s or brain damage, possess) to being a metaphysical claim about our nature. Just as we are responsive beings—something evident from the dependency into which we are born—we are also creatures who not only come into the world needing orientation, but whose existence is, in spite of all the routines of security we engage in to “protect our-selves,” metamorphic—a fact that is pressed home in sickness, in hardship, and in new relationships.

Rosenstock-Huessy had made the point in Practical Knowledge of the Soul that religion, like every other sphere of life, comes with its own speech-ways, and its linguistic practices and seals—prayers, office, ritual, and rites, and sacred names—but “its shrine preserves transformation itself, the secret of transformation.” That we are constantly being transformed is common to us all; but how we transform very much depends—and the different great religions of the world are testimony of how differently we as members of the same species may make ourselves. Likewise, the faith that bears us in our decision to carry on may be bearing us along very different life-ways. But that we are conscious of this process of being borne along and that there is faith (and by faith I do not so much mean a counter concept to knowledge, but rather trust) in the manner of the bearing is something that is intrinsic to religion.

In the main, philosophy has ignored the disposition of supplication that is intrinsic to transformation. The questions—all variants on the same question: Why did so many follow Hitler, Mao, Stalin as if they were gods? Or, why do so many join cults? Or why should/do I/ we determinedly remain true to the calling of my/our office?—all point to the deep-rooted need/desire to follow. Meaning is generally following; only very few completely open up a new pathway of reality—and this is no less the case for philosophers, however much they may consider themselves not Socratic or Platonic, who remain participants in a reality they “blasted” open.

A world is a semantic field, and names the means of our navigation within and beyond the world we are enmeshed in – semantic fields, where gods, humans and worlds were inextricable connected may, in some important ways, have been more luminous than the ostensible enlightened world where the gods are banished to the private realm of belief: even though, as my question above about fidelity to one’s professional office (one’s professional ethics) some power is still holding over one. The ethicist would like us to believe it is reason doing the holding; but I simply cannot see it that way. For once reason has been “de-metaphysicized;” it is no longer sufficiently equipped for such holding. Which is in large part why no matter how important the ethicists think they are—the overwhelming majority of people are responding to other voices in their commitments, in their relationships, and roles and offices, and spheres of solidarity.

Historically we know that the law precedes ethics. To be sure, politics as not merely the imposition or seizure or maintenance of authority, but as the institutional mediation of different interests leading to legislation begins with the Greeks. It is no accident that ethics, philosophy, and politics emerge within the one people—or rather with a certain social system in which relative freedom exists along with the division of labour and settled conditions of social reproduction. Law precedes ethics because a certain degree of sociality, division of labour and different interests, and the opportunity for social articulation enables peoples to articulate sufficiently similar concerns to arrive at common solutions. The solutions were not perfect; and in the fallout of the Peloponnesian Wars, they looked pretty terrible. But the terribleness did not lie in the lack of reason itself, but in the politically riven nature of the polis, a rivenness exacerbated by the sophists and orators, fuelling the flames of the assembly, so that practices that had been part of the community became out of control—execution, exile, property seizure and the like.

Our own age is a riven one. It is pure folly to think it can be saved by ethics or by philosophy. It can only be saved by shared commitments and healthy loves; the triumph of convivial and living associations over the purely commercial or mechanical; the imagination that reaches out and beyond closed associations so that the powers that have accrued over times and peoples freely circulate communally. Philosophy certainly has a role to play in this—it can assist us in sharpening our questions. But it can only do so if it recognizes that it is something within life not above it; a practice that cannot stand alone, a practice that is but one “moment” of a complex amalgam of interrogations and speculative conjectures that constitute what we somewhat misleadingly call the “human” or “social sciences.”

Life is not law—and unlike the authors of the Bible who scrupulously studied what occurs when we violate God’s commands, our philosophers have not even begun to take seriously the idea of there being laws of the spirit which are far more significant to us in our world-making than the laws of nature. Irrespective of our faith or philosophy, the most serious choices we have to make almost always come down to tragic alternatives. No one seriously responding to a tragic alternative would desire to elevate their choice into a principle. We who must build are constantly forced to choose between unpalatables; the philosopher glowing in the pure light of principle escapes the choke of tears and the palpitations of horror that come from the genuine circumstance. The grime of reality is reduced to the platitude of the classroom, the free and easy room where responsibility is primarily to consistency and purity of principle, to one’s own self-worth.

The moral law, says the moral philosopher Christine Korsgaard, is “the law of self-constitution, and as such, it is a constitutive principle of life itself.” Speaking of duty, Korsgaard gives these tellingly honest examples of the moral dilemmas faced by professional moralists: “We toil out to vote, telephone relatives to whom we would prefer not to speak, attend suffocatingly boring meetings at work, and do all sorts of irksome things at the behest of our friends.”

Oh, what bliss to be confronted by such monumental moral crises. But this too is a symptom of an elite that has no understanding of what is required to cultivate peace and contribute to a future that is never a creation of our design, and ever a reminder of the paltriness of our ideas, and the fragile and limited nature of what we and our reason can do.

Wayne Cristaudo is a philosopher, author, and educator, who has published over a dozen books.

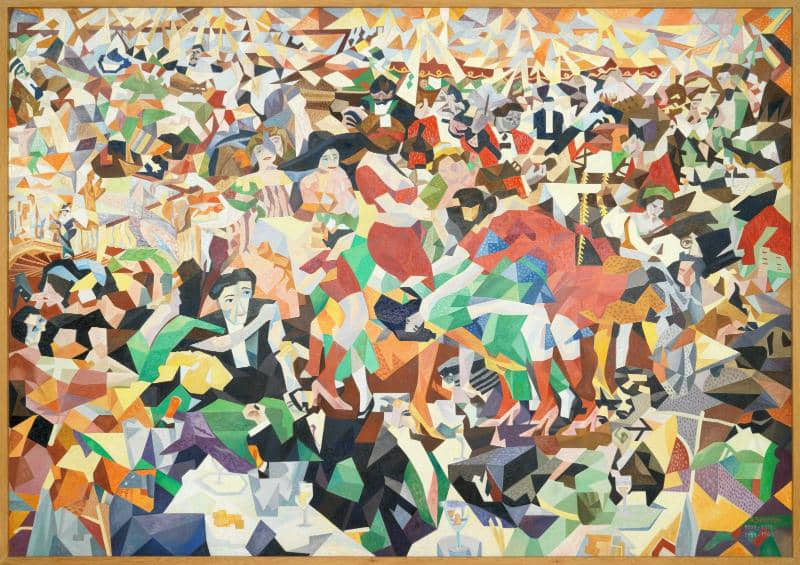

Featured: “The Post-Apocalyptic Selfie,” by David Whitlam, early 21st century.