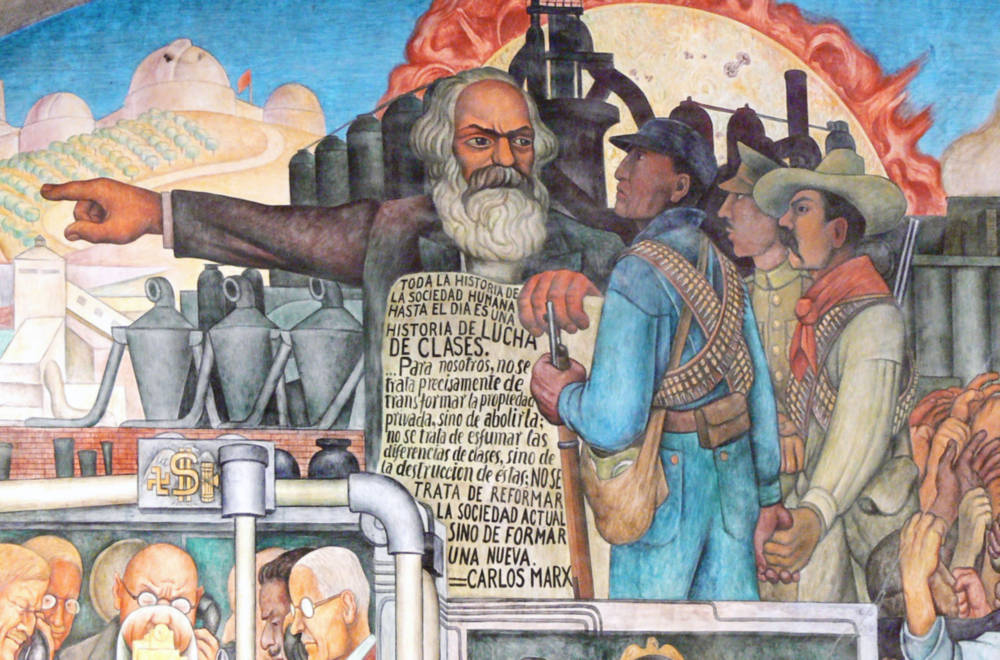

The bourgeoisie [the capitalist]… has accomplished wonders, far surpassing Egyptian Pyramids, Roman aqueducts, and Gothic Cathedrals… [D]uring its rule of scarce of one hundred years, [it] has created more massive and more colossal productive forces than… all preceding generations together… [W]hat earlier century had even a presentiment that such productive forces slumbered in the lap of social labor? (Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto, Chapter I).

Karl Marx (in collaboration with Friedrich Engels) is known as the greatest foe of capitalism. Further, his views have recently made a considerable comeback in the United States and around the world, first in the “Ivory Tower,” and from there into the culture in general. In fact, Marx made many claims about capitalism, some very positive and some very negative, but he is generally known only for the latter. However, history has shown that most of the negative things Marx said about capitalism have turned out to be false and most of the positive things he said about capitalism have turned out to be true, which leaves his exuberant praise for capitalism standing as Marx’s real legacy.

I will discuss Marx’s Marxism, here called “original Marxism,” but which also touches upon Herbert Marcuse’s Marxism of the “New Left,” a peculiar combination of Marxism with Freudian psychology that became popular in the 1960s, and the more diffuse “Cultural Marxism” that arises from an inconsistent alliance between the various species of Marxism and Post-Modernism (the relativist view which rejects the notion of objective truth).

Finally, Marxists, and others on the Left influenced by it, generally called “progressives,” often claim the moral high ground, asserting that it is the Marxists and “progressives” that care about the poor, while the evil capitalists, motivated only by the profit motive, aim to “exploit” and “oppress” them. This is the opposite of the truth.

1. Some Key Terms

It is necessary, first, to begin with a few basic definitions of several key terms, specifically, feudalism, capitalism, socialism, communism, and Marx’s “original” Marxism. The discussion of the controversial notion of “cultural Marxism” is postponed until later on in this discussion.

First, feudalism is an economic system in which feudal landlords own the land and permit the serfs to work the land in exchange for “protection.” However, feudalism appears to be exploitative since the serfs do all the actual work, while the feudal landlords take a considerable portion of what they produce.

Capitalism is an economic system founded on “free markets” in which all economic decisions are made by households or firms that are assumed to act in their own self-interest to maximize their own profit. These markets are “free” because these households and firms make their own economic decisions without being controlled by any central authority, such as the state. Economic freedom is based in the notion of private property. For example, Bill Gates, not the state, owns Microsoft. It is his to do with it as he wishes. He can even destroy the company if he wishes. That is, there is an important connection between capitalism, private property and economic freedom.

One might also add that economic freedom is a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition for political freedom. Further, since the market is free, there are normally many different private planners throughout the economy. That is, a free market presupposes competition, which, in turn, motivates the competing capitalists to continually improve the quality of their product in order to attract buyers and increase their profit. The fact that the capitalist operates on the basis of a self-interested profit motive opens it to the charge that it too, like feudalism, is exploitative. Marx certainly thought so. However, I will argue later that this gets it precisely backwards.

Socialism is an economic system in which land and capital are collectively owned. Usually this means that land and capital are owned by the state (although it could, theoretically, be owned by some smaller collective such as a commune). A socialist economy is often called a command economy because the state controls the economy in three different ways:

- It plans the allocation of resources between current consumption and future investment;

- It plans the output of each industry or firm, and

- It plans the distribution of the output (goods) between the consumers.

A socialist economy is, therefore, centrally planned because all economic decisions are made by the central commander (the state). In a socialist economy, Bill Gates does not decide what kind of computers to produce. The central planner, the state, tells him what kind of computers to produce. Note that in a socialist economy there is still private property, but it is owned by the state, not by private households or firms. The state owns and controls the airline industry, the automobile industry, the oil industry, and so on.

It is more difficult to give a concise definition of communism, but Marx thinks of communism as a more extreme purified version of socialism in which all vestiges of private property, including that held by the state, have been eliminated. In fact, Marx has theoretical considerations that commit him to the view that it is impossible to know exactly what the communist economy will be like until one actually produces it. This is reminiscent of Nancy Pelosi’s remark: “You have to pass the bill to know what’s in it.” This is quite alarming, but this particular potential objection to Marx’s communism is not something that I will take up here.

One must also carefully distinguish between Marxism and communism. There is an infamous interview in which a presenter on a New Orleans television station asks Lee Harvey Oswald, the assassin of President John Kennedy, if he is a communist, and Oswald gives a somewhat garbled reply that he is a Marxist but not a communist. The presenter, shocked, asks, “What’s the difference?”

In fact, Oswald’s position is logically consistent, if a bit odd. For communism and Marxism are not even the same kinds of theories. Marxism is a theory about historical development, specifically, the view that, starting with feudalism, feudalism necessarily breaks down and turns into capitalism, which, in turn, necessarily breaks down and turns into socialism, which, in turn, necessarily devolves into its purified form, communism. Communism, by contrast, is not a theory of historical development at all but an economic theory. Nevertheless, there is an internal relation between Marxism and communism. Specifically, the Marxist theory of historical development holds that human history is necessarily developing towards the final stage, namely, the economic system of communism.

Despite this internal connection, a communist can consistently reject Marx’s theory of historical development as complete nonsense. Further, a Marxist, who holds that human history is necessarily developing towards communism, might consistently hold that he or she is not happy about this. Such a position would be odd but only because it would represent a certain kind of extreme pessimism: The world is necessarily moving towards communism but one rejects communism. Of course, it is more likely that Oswald, not being a Rhodes Scholar, just did not understand either theory very well.

Although Marx is generally known as a “philosopher,” he claims that Marxism is a scientific theory. Marx sees his view that feudalism necessarily turns into capitalism, which in turn necessarily turns into socialism, which in turn necessarily devolves into communism as perfectly analogous with the view in the science of botany that a seed necessarily turns into a shoot, which in turn necessarily turns into a stem, which in turn necessarily turns into a bud, which in turn necessarily turns into a blossom.

Whereas Hegel had produced a view of historical development that invokes unscientific notions, e.g., the notion of the “World Spirit,” Marx purports to transforms Hegel’s romantic philosophical theory into a scientific theory, which he called dialectical materialism, in which the moving forces in human history are all empirically accessible entities, like material human conditions and behavior. In the Preface to the first German Edition of Capital, Marx compares his discovery of “the economic law of economic motion” of modern societies to Newton’s discovery of the “natural laws of motion.” As an alleged scientific theory, Marxism purposes to render scientific explanations and predictions. It should, therefore, unlike Hegel’s mystical theory, but like Newtonian mechanics, be testable.

In fact, the 19th century witnessed the production of a new range of allegedly “scientific” theories in regions that had previously been the province of philosophers and mystics, specifically, evolution, psychology, and historical development.

Darwin’s evolutionary theory purported to be a scientific theory, invoking an empirically observable mechanism (“survival of the fittest”), to explain why the observed species of living organisms have in fact evolved.

Freud’s psychology purported to be an empirical scientific theory that explains key aspects of human behavior, specifically, human neurotic behavior, by reference to sexual trauma and mental mechanisms of repression.

Finally, Marxism purports to be an empirical scientific theory that explains why human history necessarily moves from feudalism to capitalism and predicts how the capitalist society of his day will necessarily develop in the future.

2. Marx’s Basic Theory Of Historical Development

According to “original” Marxism, the single driving force of history, from feudalism to capitalism to socialism to communism, is class struggle. The guiding idea is that each of these economic systems contains certain “contradictions” that are successively eliminated as history develops. In the feudal system there is an internal “contradiction” between the feudal class that owns the land and the serfs who must labor on the land at a bare subsistence level. This “contradiction” causes the serfs to revolt against the feudal landlords in order to obtain a fairer arrangement. Thus, feudalism breaks down and gives way to the next stage, capitalism.

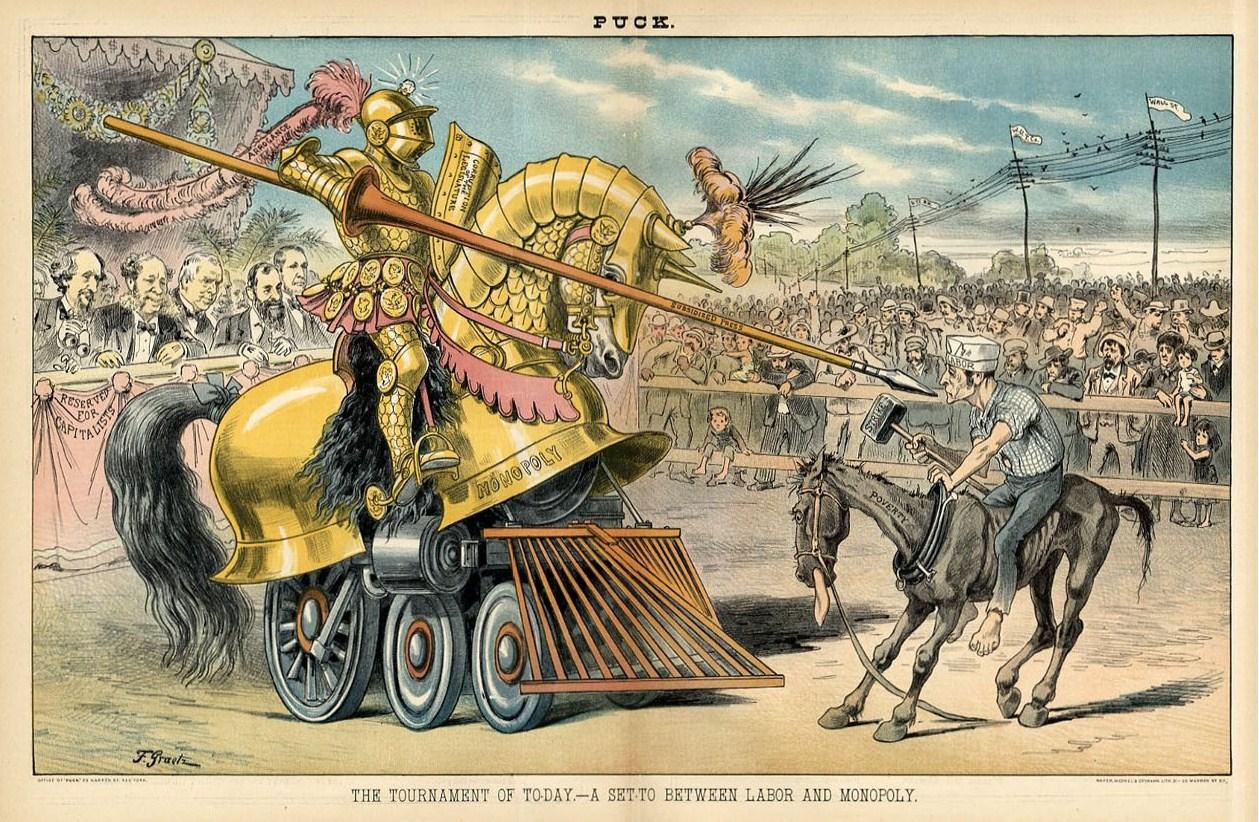

Marxists hold that capitalism solves some of the “contradictions” in feudalism, e.g., in a capitalist system people are permitted to own their own property rather that work the property of the feudal landlords, but capitalism has its own internal “contradictions.” The “contradiction” between the feudal landlord is replaced by the new “contradiction” between the capitalist, who “owns the means of production,” the factories, machines and so on, and the “workers” who are forced to work for the capitalists. There is a “contradiction” between the two because it is in the self-interest of the capitalists to maximize their profit by getting the maximum productivity out of the workers, while paying them the bare minimum. In brief, the capitalists must push the workers to work harder and harder for less and less until the “workers of the world,” pushed to the brink, revolt and create a more equitable socialist society in which “the means of production” is owned by the collective, the society as a whole, and shared out among the workers.

In a socialist society, the “contradiction” between the capitalists and the workers is, allegedly, eliminated because the workers are themselves parts of the social cooperative that “owns the means of production.” Gone are the feudal overlords who control the lives of the serfs. Gone are the capitalists who control the lives of the workers. In socialism, with these class distinctions gone, the workers are, so to speak, their own bosses, at least in theory. They are members of a cooperative group that decides for itself, not being told what to do by a separate antagonistic class, how economic resources are to be produced and distributed in society. That is the whole point of socialism. Marx divines that since there are, allegedly, no more class oppositions in socialism, the resources will be distributed equally.

In the final stage, the Marxist formula changes slightly. Since all history is driven by class struggles, and since there are no class differences in socialism, the transition from socialism to communism is not driven by class struggle. Since Marx thinks of socialism as a kind of preliminary form of communism, it need not undergo the massive revolutionary change one sees in the transition from feudalism to capitalism, or from capitalism to socialism. The problem with socialism is more minor. It is only that various vestiges of the old capitalist system still cling to the socialist system. Human beings, reared in a capitalist system that values private property, will retain some of these views and desires in the new socialist system. The transition to full-fledged communism, therefore, merely requires eliminating these vestiges in a piecemeal purification process until the full-fledged communist society, completely devoid of private property, is produced.

At this point, there are no longer even the vestiges of class distinctions. Since the dialectical process is driven by class distinctions, and since, in communism, these have all been eliminated, the dialectical process (historical development) comes to an end and human beings can, for the first time freed from the inexorable class struggle, freely decide what they want to do. As Herbert Marcuse, in the last line of his An Essay on Liberation, puts it, “For the first time in our life we shall be free to think about what we are going to do.” Note that this reflects Marx’s (alarming) view that it is impossible to say very much about the last stage of human historical development, communism, until one gets there.

Marx gives a very specific description of this pattern of historical development.

First, Marx holds that human history, like the history of a plant from seed to stem to bud to blossom, necessarily unfolds in precisely the sequence of stages he describes.

Second, Marx holds that it is not possible to skip a step, i.e., not possible to jump directly from feudalism to socialism by skipping the capitalist phase, any more than it is possible to pass from stem to blossom in the history of a plant by skipping the bud stage. For this reason, it would be a mistake, impossible of success, if an overly enthusiastic communist were to try to push the feudal phase to break down into the socialist phase by skipping over the intermediary capitalist stage. It is entirely necessary that human society passes through the specified sequence of stages in the proper order.

Third, the breakdown of one economic stage of a society into the next stage also follows a particular pattern. For example, given two capitalist societies in different stages of development, the one that is at the more advanced stage will break down into socialism before the one that is still at an earlier stage. If, for example, in the late 19th century, England is at a more advanced stage of capitalism than America, then England will fall to a socialist revolution before America does. Marx has a particular picture. In its early stages, capitalism is not fully developed. As such, the “contradictions” in capitalism are also not fully developed.

The further development of capitalism, so to speak, further exposes both the negative aspect of capitalism. Accordingly, there is no danger that capitalism will collapse into socialism at those early stages. It will only be when the “contradictions” in capitalism are fully developed, that is, when capitalism itself is fully developed, that the socialist revolution can and must happen. Since Marx, banished from Germany, was living in England, the most advanced capitalist economy at the time, he witnessed William Blake’s “dark Satanic mills” in which child laborers are mercilessly exploited in order to maximize the profits of the capitalist. Accordingly, he predicted that the socialist revolution would first occur in the most advanced capitalist economy at the time, England.

Finally, Marx explicitly states that the transition from capitalism to socialism involves violence. In his 1872 speech, “The Possibility of Non-Violent Revolution,” he states that “we must also recognize that the lever of our revolution must be force; it is force to which we must someday appeal if we are to erect the rule of labor.”

Marx also endorses the need for dictatorship. In his Critique of the Gotha Program, Marx describes the “rule of labor” in the transition to socialism as “the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat.”

Similarly, Marcuse endorses the need for both force and dictatorship: “The [idea] of “educational dictatorship” … [is] easy to ridicule but hard to refute … [for] to the degree to which the slaves [the American people] have been preconditioned to … be content … in that role … they must be “forced to be free.” (One Dimensional Man, Chap. 2).

Force and dictatorship are central to “original” Marxism. Indeed, this is only common sense. Since people will not freely give up the private property that they believe they have earned, the Marxist or socialist will have to take it from them by force.

3. Marx’s Exuberant Praise Of Capitalism

Although Karl Marx, the man, was emotionally invested in the eventual triumph of communism, it is important to note that Karl Marx the aspiring scientist was no more emotionally invested in the triumph of communism than a botanist is emotionally invested in the fact that the bud normally turns into a blossom. Karl Marx qua scientist simply purports to describe the alleged laws of human historical development, just as Isaac Newton simply describes the laws of mechanics. Karl Marx the scientist simply holds that this is how history does develop, namely, from feudalism to capitalism to socialism to communism in accord with a certain necessary pattern. Qua scientist, Karl Marx does not hold that capitalism ought to collapse into socialism. Karl Marx the scientist simply holds that this is what, in fact, happens and what must happen.

This is, perhaps, why Karl Marx, unlike many of his more enthusiastic followers over the years, was able to acknowledge the enormous virtues of capitalism. Indeed, Marx’s praise for capitalism in the Communist Manifesto is far more enthusiastic than that of many current defenders of capitalism.

Capitalism, Marx tells us, has produced “wonders” far beyond anything produced by the ancient Egyptian, Roman, or Gothic architects. Since those ancient “wonders” are, even today, reckoned among the great accomplishments of humanity, Marx’s elevation of the “wonders” of capitalism above them is high praise indeed.

Further, Marx stresses that capitalism has accomplished all this in a very brief span of about 100 years! During this brief span of time, capitalism has released “more massive and more colossal productive forces” than “all preceding generations” combined! No one in earlier centuries has even had a “presentiment” that such “massive … productive forces” were even possible.

Then, Marx goes on in the same passages to explain that capitalism, by unleashing these massive productive forces, does not merely improve economic conditions, but, rather, “In place of the old local and national seclusion and self-sufficiency, we have intercourse in every direction, universal inter-dependence of nations. And as in material, so also in intellectual production. The intellectual creations of individual nations become common property. National one-sidedness and narrow-mindedness become more and more impossible, and from the numerous national and local literatures, there arises a world literature… The bourgeois [capitalists], by the rapid improvement of all instruments of production, by the immensely facilitated means of communication, draws all, even the most barbarian nations into civilization. The cheap prices of commodities are the heavy artillery with which it batters down all Chinese walls, with which it forces the barbarians’ intensely obstinate hatred of foreigners to capitulate.”

That is, capitalism draws the various nations out of their prejudicial self-seclusion and fosters intercourse and interdependence between them. This is not merely economic interdependence but intellectual interdependence as well, leading even to the establishment of a “world literature.” The Chinese and the Japanese now read Shakespeare and the English-speaking West reads the Tao te-Ching and Zen poetry. Thus, capitalism begins to break down “national one-sidedness and narrow mindedness,” which, in turn, brings “civilization” to “barbarian” nations and forces the different peoples to end their “intensely obstinate hatred” of the other.

It needs to be stressed that it is in the very nature of Marxism that capitalism must produce many goods results. Since Marxism has a developmental view of history, in which human societies move through a series of ever-improving stages toward the final resolution at the end, and since capitalism is the intermediary stage just below the glorious advent of socialism, Marx is committed to hold that capitalism must, and has in fact, created many goods results.

Thus, the contemporary “Marxist” who, failing to understand the inner logic of Marx’s system, expresses bitter hatred for the evils of capitalism, is a bit like a botanist who expresses bitter hatred for the bud because it is not the blossom. Marx, by contrast, recognizes that the bud is entirely necessary in order to get the blossom; and, therefore, following the logic of his own system, he is committed, by analogy, to acknowledge the greatness of capitalism. That is why, in the passages quoted earlier, Marx expresses the same kind of wonder at the accomplishments of capitalism that a botanist might express at the blossoming of life in a plant.

For Marx, capitalism is, so to speak, a necessary stage in the blossoming of human development. It is in some ways a shame that Marx is not with us today to correct some of the misunderstandings and excesses of his confused emotion-driven progeny in the “Ivory tower” and the Hollywood hills.

4. Marxism Falsified By Historical Facts

The problem, for original Marxism, is not that capitalism has not accomplished a great deal of good, but that, on Marx’s view, will necessarily collapse as its (alleged) internal “contradictions” become manifest and give way to the even more wondrous economic blossoming of socialism.

However, this has just has not happened as Marx predicted. Whereas Marx predicted that the socialist revolution will occur first in England, where capitalism was most advanced at the time, it did not occur in England but in Russia in 1917, which was still in an abject feudal state at the time. Indeed, although the English economy has become more socialistic in some ways, this has been due to an evolutionary process and a great deal of capitalism has been retained. No socialist revolution has ever occurred in England.

Marx is wrong on at least two counts. First, he was wrong that the revolution would occur first in the most advanced capitalist country at the time, England. Second, he was wrong that it is not possible to “skip a step” and go directly from feudalism to socialism, which happened in Russia in 1917. According to the allegedly “scientific” Marxism, none of this was supposed to happen in the way it did in fact happen. The observed historical facts contradict Marxist theory.

Marxism was also wrong in an even more obvious way that should have been evident to Marx himself, which, surprisingly, has not received sufficient attention. Note that prediction is always risky. Einstein took a great risk when, on the basis of his theory of general relativity, he predicted that when Mercury passes behind the sun, on a certain date, its light rays would be bent by the sun’s gravitational field in an unexpected way that enables observers on Earth to see it when it is still behind the sun. Since that specific rare event had not been observed before, who could be sure what would happen? As it turned out, Einstein was right. His risky prediction was verified. That is good science. Had Mercury not been observed as predicted, a good scientist like Einstein would have been forced to go back to the drawing board and reject or revise his theory.

By contrast, explanation of past events is normally not so risky. For when one attempts to explain past events, one normally already knows the facts about what happened. One would, therefore, expect Marxism to do quite well in its explanation of the collapse of feudalism and the rise of capitalism. All Marx had to do was to make sure his theory fit the known historical facts.

However, as Milton Friedman has pointed out, Marx never solved the problem of feudalism that was staring him in the face. The collapse of feudalism and rise of capitalism did not come about as the result of any “class struggle” between serfs and feudal landlords. There was no “revolution” of that sort at all. Feudalism collapsed for a multiplicity of reasons that had nothing to do with its alleged “internal contradictions,” but because of a series of external historical accidents. Recall that there is no place in Marxism for accidents. The inexorable onward march of history is necessary!

One of these historical accidents was the opening up of trade around the Mediterranean and the emergence of the “Black Death” plague (probably brought into Europe via Turkey from China) in the 14th century that killed between 30 and 50 percent of the European population. The combination of these two external historical accidents simply made labor much more valuable. As a result, serfs were enabled to walk off their feudal plots of land and travel to the cities where their labor in that newly emerged market commanded much better wages than they received from their feudal masters. Thus, feudalism collapsed, not because of any Marxist “internal contradictions” in feudalism, but because of accidental external developments that simply made the free labor market of capitalism much more desirable!

In summary, Marxist theory is refuted by the facts.

First, two of Marx’s most basic predictions turned out to be false. The predicted socialist revolution did not occur in the most advanced capitalist economy of the time, England. It occurred in Russia by skipping a step and going directly from a feudal economy to socialism, which is, for Marx, not possible.

Second, even more surprising, Marxism does not correctly describe or explain the collapse of feudalism and the rise of capitalism. There was no rising up of serfs in a “revolution” leading to the demise of feudalism and the emergence of capitalism. This was already evident in Marx’s own history books. That is, Marxist theory fails, and rather spectacularly, on all major fronts considered here. One wonders, therefore, why Marxism, like the monster in a cheap monster movie, keeps coming back after one had been entirely certain that it is finally, completely dead.

5. Marxism Is Quasi-Religious Dogma

Karl Popper states a powerful objection against all three of the remarkable alleged new “sciences” that appeared in the 19th century: Darwin’s evolutionary theory, Freudian psychology and Marxist historical materialism. Popper does not argue that these “theories” are false but that they are not even scientific theories. That is, Darwin, Freud and Marx each purport to have created a new science, but there is, in each case, something fraudulent about the claim to scientific status.

In order to make his argument, Popper must provide a criterion that a theory must satisfy in order to be judged to be a genuine scientific theory. Part of his criterion is that the theory must be falsifiable. That is, theory T is a genuine scientific theory only if there are precise specifiable conditions which, if these were to be observed to be the case, would show that the theory is false.

Once again, to avoid any possible misunderstanding, Popper does not argue that these three kinds of theories are false. He argues that these three kinds of theories are not even falsifiable because there is either something about the way they are logically structured or the way they are applied in practice that makes it impossible to falsify them.

Popper’s reasons for judging that these three types of theories are not falsifiable (ergo, not scientific), is different in each case. Unfortunately, since Marxism, not Darwinian or Freudian theory, is our present subject, only Popper’s critique of Marxist historical materialism can be considered in detail here.

Popper’s argument that Marxist historical materialism is not a genuine science is that when Marxist explanations or predictions turn out to be false, which they regularly do, Marxists do not, as a genuine scientist would in such circumstances, go back to the drawing board and revise their theory to take account of the recalcitrant facts.

Recall that, as argued in the previous section, the Marxist explanation that feudalism collapsed because of a “class struggle” between the feudal landlords and the serfs is not verified by the facts. Rather, the emergence of the “Black Death” in Europe had more to do with the collapse of feudalism than any alleged “internal contradictions” in feudalism.

Recall also that the great socialist revolution did not occur in England, where Marx predicted it would occur, but rather that capitalism in England, in a plethora of ways, evolved into better and better forms, for example, in the development of a large middle class that was not in the least interested in a revolution.

Finally, recall that the socialist revolution did occur in Russia, which, as a feudal society, is precisely where Marxism predicts it cannot occur. How, in general, did Marxist “theorists” react to such failures in Marxist theory?

To put it bluntly, they cheated. Consider the fact that the socialist revolution occurred in Russia, precisely where Marxism predicts it cannot occur. Many Marxists have argued that the reason Russia “skipped a step” and went directly from feudalism to socialism is because of the emergence of the great genius of Lenin. That is, normally, the historical process must proceed as described in Marxist theory from feudalism to capitalism to socialism, but in this one special case Lenin appeared and, by virtue of his unique understanding of the historical process, he was able to push Russia, so to speak, fast forward directly from feudalism to socialism.

The problem with that is that it is the essence of Marxism that the development of human history is determined by great impersonal economic forces alone, specifically, class struggle, not by the emergence of individuals. If the development of human history can be altered by the appearance of some individual genius, a Socrates, a Newton, or a Lenin, then obviously Marxist theory cannot predict the future development of human history. For the one thing that Marxist theory cannot, in principle, take account of is individual genius (or even individuality in general).

Just as Newtonian mechanics must fail if individual chunks of matter can sometimes “choose” to diverge from Newton’s laws of mechanical nature and begin to move in their own individual way, Marxist theory must fail if individual human beings, whether this be Socrates, Newton or Lenin can move history in their own individual ways to transgress the vast impersonal, inexorable economic laws of human historical development “discovered” by Marx.

However, faced with these falsifying observations, Marxists have typically made ad hoc hypotheses, e.g., that this direct jump was due to the unique genius of Lenin, solely in order to preserve their theory from falsification. Ironically, although Marx, fancying himself a “scientist” (not some dreamy philosopher or prophet), said that “religion,” in contradistinction to science, “is the opiate of the masses,” Marxism, in the hands of many subsequent “Marxists,” itself became a quasi-religious opiate of the Left that must be protected from falsification, i.e., from the facts, at all costs.

6. All “Historicist” Theories Fail

Popper does not merely argue that Marxism is in fact unfalsifiable and unscientific. He also offers an explanation why all historicist theories, that is, theories that purport to predict the future development of human history, cannot, in principle, be correct. Many “philosophers,” including Plato, Malthus, Hegel, Marx, and Spengler have produced historicist theories that purport to predict how human history must play out. Popper argues there is a fatal, and rather obvious, flaw in all such “historicist” theories.

Popper’s argument is based on the premise that any theory that purports to predict how human history will develop must fail because no theory can, in principle, take account of the future growth of human knowledge. F.A Hayek agrees: “The mind can never foresee its own advance.” (The Constitution of Liberty, Part I, Chap. 2). That is, since it is impossible in principle to know how human knowledge will develop (because, roughly, that would require one to know something before one knows it), and since the development of human history depends upon the growth of human knowledge, it is impossible in principle to predict how human history will play out.

Consider a simple example first. The British economist Malthus (1766-1834), in his Essay on the Principle of Population invoked his “law of diminishing returns” to argue that the trends in population growth in his era must inevitably end in mass starvation. Specifically, he argued that population, when unchecked, tends to grow in a geometrical ratio, while “subsistence” grows only in an arithmetic ratio” and a “slight acquaintance with numbers will show the immensity of the first power in comparison with the second.”

Thus, Malthus infers that the point will quickly be reached in which the capacity for food production will not be able to keep up with the needs of the rapidly growing population, ending, inevitably, in mass starvation. But Malthus thinks of the human race too much on analogy with a bacterial colony on an agar base in a Petrie dish. The bacterial colony begins growing at first at an exponential rate when its “food” is plentiful. However, the “colony” soon expands to the point that the finite quantity of the food in the agar base in the Petrie dish runs out leading to mass starvation and the complete collapse of the “colony.”

Malthus also forgets that human beings are not like bacteria. Human beings can become aware of the limitations in themselves and in their environment and take measures to escape his tragic predictions. He forgets that human knowledge will itself increase during this period in ways that he cannot possibly predict. Scientists may discover new kinds of fertilizer or cultivate new more productive species of crops that massively increase the level of food production for a given area of land. New more efficient methods for storing food without spoilage may be discovered and so on.

Malthus’ pessimistic predictions about the inevitably of mass starvation are relative to a certain set of assumptions, e.g., Malthus could not possibly have known anything about current methods in the genetic modification of food, or of human beings themselves, that will enable humanity to sustain itself indefinitely. Taking a bit of poetic license, one might put this by saying that Malthus just assumes that human knowledge will not also increase at a geometrical rate to keep up with the geometrical growth of human population!

In fact, Marxism fails to account for the growth of human knowledge in an even more intimate way. Whereas Popper’s general point is that historicist views cannot possibly take account of the growth of human knowledge, Marx himself provided the new knowledge required to ensure that his own predictions fail! For Marx’s publication of his theories about the “internal contradictions” in capitalism itself represents a growth in human knowledge. His publication of these theories, therefore, adds a factor to the historical equation that is not taken account of within Marx’s theories, namely, the factor that the capitalists themselves can read Marx’s works, learn about those pitfalls in capitalism, and take measures to neutralize them.

The irony is that capitalists, having read Marx’s works, and having no pressing desire for their head to end up on a stake in the town square, can change their behavior in order to prevent Marx’s predicted socialist revolution. For what the great enemy of capitalism, Karl Marx, has actually provided in his published works is a handbook for capitalists to enable them to prevent the glorious socialist revolution. There are, in fact, few thinkers who have done more to protect capitalism from the socialist uprising than Karl Marx. For this alone, capitalists owe Marx a great debt of gratitude.

7. Marxism Replaced By “Cultural Marxism”

Since the “workers of the world” did not go along with the Marxist script and rise up against their capitalist oppressors in a violent socialist revolution, but rather became more and more enamored with capitalism, one might have expected that Marxism would quietly wither away like so many other unsustainable “philosophical” theories. However, since Marxism had become too important to too many people, even becoming a “battle cry” in many parts of the globe which resulted in a plethora of murders, it was destined to be revived, not as a true philosophical or “scientific” theory, but as a cultural force, that is, as “cultural Marxism.”

This is not the typical fate of most failed “philosophical” theories. When, for example, Bertrand Russell’s “logicist” attempt to reduce arithmetic to logic failed, one does see it live on in massive worldwide movements that insist that despite the decisive objections, the failed doctrine must be retained anyways as some kind of cultural tool. At most, one finds a few diehard scholars tinkering with Russell’s “logicism” in some obscure academic history journal or other, perhaps attempting to revive it – which is fair enough. It was, however, inevitable that Marxism would be treated differently and would reappear in the culture in new more deceptive forms.

To hear the cultural Marxists in the “news” and print media describe it, the term, “cultural Marxism” is an extremely controversial term. Wikipedia has an article titled, “The Conspiracy Theory of Cultural Marxism.” Normally, in a real Encyclopedia, as opposed to an indoctrination tool, one would expect to find an article titled “Cultural Marxism” in which some recognized experts are cited who argue that the phenomenon of “cultural Marxism” is real and others who argue that it is not real and, perhaps, that the view that there is such thing as “cultural Marxism” is a conspiracy theory. That is what used to be understood under the rubric of a “fair discussion” in the United States.

By contrast, Wikipedia, by titling its article as it does, is “framing” the discussion of “cultural Marxism” so that the reader begins with a negative attitude towards the whole notion before they even read a single word. The psychological notion of framing is roughly equivalent to the ordinary notion of “spinning.” One “spins” a story, often deceptively, in a way favorable to one’s own agenda in order to prejudice one’s opponents against it, and, in fact, Wikipedia is simply spinning the notion of “cultural Marxism” so that it is already framed by the title for the reader as a discredited notion. Only extremely unsavory “conspiracy theorists” believe that there is such a thing as “cultural Marxism.”

The Wikipedia article proceeds to associate “cultural Marxism” with the extremist Anders Breivik who gunned down 77 people, including many children, in Denmark in 2011 because he referred to “cultural Marxism” in his Manifesto. There is no need to respond to that “argument.” In brief, the Wikipedia article creates a “straw man” notion of “cultural Marxism” that can easily be knocked down and then ritually proceeds to knock it down.

Needless to say, my present claim that the phenomenon of “cultural Marxism” is real does not support any doctrine that justifies any such violent lunacy. For the sake of brevity, I discuss only one example of what I mean by “cultural Marxism” in any detail, the unjustifiable censorship of conservatives and President Trump by Facebook, Twitter and the “news” media that has recently distorted the “culture” in the United States. However, I do briefly mention several other current “cultural Marxist” phenomena that could be profitably taken up in future discussions.

Prior to the presidential election of 2020, Facebook, Twitter and many outlets in the “mainstream media” began censoring “conservatives” on the grounds that they “violate their community standards,” and censoring President Trump because he (allegedly) lies too much. As this article is being written, circa Dec. 4th, 2020, Anderson Cooper announced that CNN would not be showing the speech that President Trump described as “the most important speech he ever made” on the grounds that it is (allegedly) full of lies.

One would think that since most of the anchors and presenters on these “news” outlets have been raised in the United States, as opposed to the Soviet Union or Cuba, it would not be necessary to explain why there is no possible justification whatsoever for censoring conservatives or President Trump on such grounds, that is, no need to explain that it is the “news” media’s job to present all sides of the issues neutrally, because it is the American people alone, in free and fair elections, who are entitled to decide who is lying and who is not. It used to be understood, generally by the 8th grade, that to begin censoring is to start down the road to full tyranny. But, unfortunately, given what has become of our “educational system” over the decades, that is no longer true.

In any case, it is easy enough to determine who is lying in any given case by observing who needs to censor and who does not. However, that particular point goes beyond my present topic. My present more limited aim is only to point out that the “justification,” such as it is, currently offered for the censorship of conservatives and President Trump has its provenance in the “New Left” “Marxism” of Herbert Marcuse that became the rage on American university campuses in the 1960s with the rise of the psychedelic drug culture. That is, Marcuse’s “justification” of censorship, currently practiced by a plethora of privileged organizations like Twitter and Facebook and CNN is itself an example of “cultural Marxism.”

In his essay, “Repressive Tolerance,” the “New Left” “Marxist” Herbert Marcuse begins with a statement of the ultimate conclusion of his essay: “The conclusion reached is that the realization of the objective of tolerance would call for intolerance toward prevailing policies, attitudes, opinions, and the extension of tolerance to policies, attitudes, and opinions which are outlawed or suppressed.”

That is, Marcuse holds that “objective tolerance” actually requires “intolerance” by Marxists, towards established views. Tolerance is intolerance towards the opponents of Marxism. Yes of course! And “War is peace, freedom is slavery, ignorance is strength.” (George Orwell, 1984).

Marcuse’s argument for his “repressive tolerance” (i.e., intolerant repression of those he disagrees with) is that even a “liberal democracy,” which purports to allow for an objectively completely free discussion, may actually conceal a “totalitarian organization:” “…In a democracy with totalitarian organization, objectivity may fulfil a very different function, namely, to foster a mental attitude which tends to obliterate the difference between true and false, information and indoctrination, right and wrong. In fact, the decision between opposed opinions has been made before the presentation and discussion get under way–made, not by a conspiracy or a sponsor or a publisher, not by any dictatorship, but rather by the ‘normal course of events.”

That is, since, even in a liberal democracy that guarantees freedom of speech, there is already an established body of opinion that, “in the normal course of events,” resists “alternative” views, the deck is stacked against the Marxists and other rebels. For this reason, “persuasion through discussion and the equal presentation of opposites… easily lose their liberating force… [and] are far more likely to strengthen the established thesis and to repel the alternatives.” Marcuse is clearly disturbed that the Marxists seem always to lose the arguments with “the establishment,” thereby leaving “the establishment” even stronger.

There must, Marcuse is certain, be a reason the Marxists always lose the argument and it cannot be that they have dreadful arguments (See IV, V and VI above). Since the Marxists are completely certain of their views, and since they are certain that they must lose the arguments because of an entrenched advantage “the establishment” possesses “in the normal course of events,” Marcuse infers that Marxists are justified in intolerance towards the established views that the Marxists do not see as “liberating” enough.

This sort of intolerance is currently on full view in the censorship of conservatives on Facebook, Twitter and the “mainstream media.” It is on full display in the attacks on gay conservative Milo Yiannopoulos at the “home” of the “free speech” movement, Berkeley, California, for attempting to state views the Left sees as contradicting its view of “liberation.” It is on display on the attacks on teachers, even “progressive” professors, at Evergreen College for stating simple disagreements with leftist students. It is on display in the censorship of the president of the United States, and the 74 million people who voted for him, for having the temerity to disagree with their self-appointed cultural overlords… and so on. In fact, Marcuse’s argument for leftist intolerance against “the establishment” is a textbook case of “question begging.” For the question what is genuinely “liberating” cannot be legitimately assumed by Marcuse but must itself be part of the free and fair discussion.

If Marcuse sat on high above the human fray like a god with a privileged view of the truth, he would be in a position to judge that the establishment has an unfair advantage in debates with Marxists. However, he enjoys no such position. He and his fellow Marxists are human beings, like any other, subject to the same foibles and weaknesses as everyone else. That is, Marcuse simply begs the question against the view that capitalism is more liberating than Marxism. One would think, given Marx’s own exuberant praise for capitalism (discussed in section 3 above), this would have occurred to Marcuse, at least as a possibility. But, apparently, it did not.

Many on the Left today, such as the uberwealthy owners of Facebook, Twitter and “mainstream media” establishments, also, apparently, think they occupy such a superior position, like gods, above the “basket of deplorable” “workers of the world” that they are justified in censoring both them and the president when the latter decline to go along with the script. However, if these uberwealthy cultural actors do occupy some superior position over the “basket of deplorables,” it is their vast accumulation of capitalist dollars, sometimes by dishonest means, that grant them this position, not any privileged relationship to the truth.

One might add, as an additional example of “cultural Marxism,” Alexandria Ocasio Cortez’s (AOC’s) complaint in February of 2019 that workers are exploited because they are regularly paid less than the value they create. After all, it is the workers who transform the cow into a pair of shoes that can be sold in the market for a price. The market “value” of the shoes is, therefore, completely created by the labourers. But that is just a re-statement of Marx’s theory of “surplus value,” the view that workers in a capitalist society are not paid for the full value of the wealth they create.

Let us assume Marx and AOC are right. What AOC, who, apparently, has a bachelor’s degree in economics from Boston University, fails to point out is that if the worker were paid the full value of what they “create” from the cow, the factory in which they work would go out of business due to an inability to meet their expenses. That would put the worker who “creates” the shoes on the unemployment line, because the factory in which the cow is transformed into shoes will have expenses that cannot be paid. How, precisely, is providing the worker with a job “oppressing” them? But this is no place for a basic lesson in economics or arithmetic. F.A. Hayek is reported to have said that “If socialists understood economics, they would not be socialists.” (Dan Duggar, “Letter to the Editor”).

One might also mention as “cultural Marxism” the sustained contemporary attacks by “progressives” on traditional religious organizations, the family, and the police. The prejudice against traditional religion, the family, and the police comes straight out of Marxist texts. For Marx, religion is “the opiate of the masses,” and the police are an instrument of the capitalists to control the working class. Governor Cuomo’s differential treatment of religious and secular gatherings during the COVID-19 lockdowns is a case in point. The same is true of fact-free “progressive” attacks on the police. To take just one example, “progressives” still routinely use the “hands up, don’t shoot!” slogan from the 2014 Michael Brown case even though the Obama-Holder justice department exonerated police officer Wilson. Given, however, that “progressives” and other “cultural Marxists” have dispensed with the depressing notion of truth, they have been enabled to make this slogan a very useful but false “narrative.”

It does not matter to many of these “cultural Marxists” that many of the poor actually want a greater police presence in their communities. Since, according to Marcuse, the “deplorables” have been deceived by the capitalist oppressors, it is not necessary to take their views into account. Rather, the “basket of deplorables” must, as Marcuse, in One Dimensional Man (pp. 43-44), makes abundantly clear, be “forced to be free.”

Marcuse, like Marx, makes clear that force will be needed to subdue the recalcitrant workers who decline to follow the script. The Marxists certainly cannot permit the “deplorables” to state what they mean by “freedom.” The notion of freedom will be defined by the all-knowing Marxist elites and “forced” on the “basket of deplorables” who, in their appalling ignorance, consistently reject it.

It is crucial to point out that the present claim is not that Gov. Cuomo, Anderson Cooper and other members of the privileged elites are card-carrying Marxists. That completely misunderstands the argument. For the last thing these uberwealthy and powerful elites want is a real Marxist revolution. One does not even want to think about what that would do to the price or availability of Dom Perignon champagne or white truffle oil.

What they want is to enjoy all the fruits of capitalism for themselves even as they display their “moral” bona fides by imposing various Marxist views about censorship, religion, the family and the police on the “deplorables,” who manifestly do not want them. Indeed, these self-gratifying elites see themselves, just as Marcuse sees himself, as moral warriors doing what Marx’s great historical dialectic failed to do when they “force” the “basket of deplorables” to be “free,” not, of course, as the “basket of deplorables” understand freedom, but as they, the “cultural Marxists” define it for them.

“Cultural Marxism” is as real as the censorship of conservatives and the president by the aforementioned massive cultural institutions. It is also real in the constant assaults by “progressives” on the police, the nuclear family and traditional religions, especially Christianity. The purported justifications for this kind of censorship by “progressives” traces precisely to Marcuse’s Marxist notion of “repressive tolerance.”

But Marcuse’s argument for his notion of “repressive tolerance” rests on the childish assumption that Marxists are superior to “deplorable” “workers of the world” whom they purport to represent – that is, it rests, ironically, on the elitism of the all-seeing Marxists or “progressives.”

The truly astonishing fact is that the transparent problem with Marcuse’s self-indulgent question-begging argument for the right to censor his political opponents does not require a journey into the obscure nature of “dialectical materialism” but is as close as the nearest freshman critical reasoning textbook.

8. Marxism In Universities

The common view that there is a strong presence of various species of Marxism, including “cultural Marxism,” in our universities has been challenged. For example, Byron Caplan reports that as the Iron Curtain crumbled, people often joked that “Marxism is dead everywhere… except at American Universities” – but is this an exaggeration?

A representative 2006 survey of university professors by Neil Gross and Solon Simmons concludes that, except in isolated areas, the percentage of Marxist university professors is very small. Specifically, only 17.6% of professors in the social sciences and 5% in the humanities identify as Marxists, but that this number falls to 1.9% in business, 0.7% in computer sciences and engineering, and 0% in the physical and biological sciences. This works out to a mere 3% of university professors overall. Gross and Simmons conclude that this is not particularly alarming.

In fact, Gross and Simmons’ reassuring conclusion is wrong for a number of reasons. Even given their own formulation of the results, they only take account of those professors who self-identify as Marxists. This does not account for the many additional professors who may subscribe to Marxist views but either do not admit to this or do not even know themselves the Marxist provenance of their views. Nor does it apply to the much larger group of “cultural Marxists” in which the “original” Marxist views are reformulated in new, sometimes deceptive, terms to avoid direct association with the discredited Marxist theory of the necessary “class struggle.”

Whereas it was central to original Marxism that classes are defined exclusively in economic terms (ownership of the “means of production”), the purely economic classes of Marx have been replaced by “classes” redefined by “cultural Marxists” in racial, gender or sexual preference terms, which then, in a project called “intersectionality,” must be artificially stitched together into “class” of highly diverse oppressed people. Instead of the class struggle between the “capitalists” and the “proletariat workers,” each defined in strict economic terms, the new “cultural Marxists” refer to the struggle between the “Patriarchy” and the oppressed “class” of females, or between “systemic racism” and the oppressed “class” of “people of color.”

This revisionary project is facilitated by the fact that contemporary “cultural Marxists” represent a curious combination of Marxism with “Post-modernism.” A great deal could be said about Post-Modernism, and in fact, in another context, deserves to be said, but one thing that is manifestly clear is that classical Marxism is incompatible with the Post-Modernist’s relativist replacement of the idea that there is an objective truth, with the idea that there are simply different “narratives” about human history.

One should not be surprised when the Post-modernist “narratives” about “the Patriarchy” and “systemic oppression” turn out to be new unfalsifiable “theories.” For, when the Post-modernists, conveniently, abandon the notion of truth, they also abandon the idea that one can objectively falsify any of these “narratives.”

Indeed, the point and utility of these “narratives” is precisely that it is impossible to falsify them. But since, according to the Post-Modernists, there is no objective truth in these areas anyways, they are still very useful.

Marx, by contrast, was sufficiently old fashioned that he still believed in objective truth and in Marxism as a “science” that will sit alongside the other objectively true sciences like Newtonian mechanics. Marx did not think of Marxism as a mere useful “narrative.”

Thus, although it may be true that only a relatively small percent of professors in the social sciences and the humanities explicitly self-identify as “Marxists,” the relativist language of the “cultural Marxists’” unfalsifiable assertions of “systemic racism and sexism” by “the Patriarchy” are ubiquitous on university campuses. The 2006 study may be correct that there are relatively few self-identifying “original” Marxists on campus; but there is an enormous additional number of professors on campus that embrace the safety of a whole raft of the vague unfalsifiable “narratives” of the Post-Modernist “cultural Marxists.”

It is important to be clear that each of these groups cited by the “cultural Marxists,” black people, Native Americans, women, gay people, transgender people and others have every right to raise objections about the way their group has been treated – and some of these complaints will be correct. The present point is simply that “cultural Marxism” is an artificial framework invented to frame these issues under one unifying quasi-Marxist formula that has far less to do with the reality (another difficult notion for “cultural Marxists”) than it does with social activism.

Unfortunately, linking together what is different just to subsume different issues under some impressive sounding net of jargon can distort the original problems. To take just one example, although there is an ostensible alliance between the “gay” and the transgender community, some “gay” establishments do not permit entry to transgendered individuals on the grounds that the latter are not really “gay.” The unity between the two communities that is useful at election time rapidly disappears on the ground. Further, the tension between the transgender and the “gay” communities can have nothing to do with “the Patriarchy” or “systemic racism.”

The reason gays have tensions with transgender people is the same reason that black people sometimes have problems with brown people, or Westerners sometimes have problems with Asians, or Chinese sometimes have problems with Japanese, or the Northern hemisphere sometimes has problems with the southern hemisphere, or males sometimes have problems with females, or “old money” sometimes has problems with “new money,” or moderate feminists have problems with radical feminists and so on is that this is the way human beings are. These tensions and “struggles” are universal and cut across all the different classifications of human beings. These conflicts cannot be reduced to any simple formula suitable for a sociology syllabus or a fortune cookie.

Since much contemporary “cultural Marxism” is really an inconsistent combination of relativist Post-Modernism and “original” Marxism, the resulting view, having abandoned the notion of truth and, with that, the need to provide intellectually cogent definitions, argument, and evidence, is really an easy conglomerate of unfalsifiable “narratives” that are prized precisely because they are unfalsifiable.

Whereas an “original” Marxist, like, for example, Maurice Cornforth, felt the need to reply vigorously to Popper’s charge that Marxism had become an unfalsifiable dogma, the contemporary “cultural Marxist” takes grateful refuge in precisely that unfalsifiability. Since many of the “doctrines” of the “cultural” Marxists are unfalsifiable “narratives,” there is no chance that one of the remaining intellectually rigorous persons will falsify them in the way that “original” Marxism was falsified.

9. Why Are Marxist Theories Popular?

There is another reason why Marxism has enjoyed considerable popularity and why, in some circles, it continues to do so, namely the extraordinary simplicity of its basic picture. The first sentence of Section I of the Communist Manifesto is: “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.”

That is, all of human history, the astonishing genius of ancient Greece, including, for example, the great ancient Greek tragedians, scientists, artists, mathematicians and philosophers, the magnificent development of Roman Law, the emergence of Christianity and Islam, the artistic glories of the European Renaissance, the simultaneous development of the differential calculus by Pascal, Newton and Leibniz, the customs concerning gender relations in China and Japan and throughout all human history, the development of existentialism, phenomenology and analytical philosophy in the early 20th century and so on, are all “explained” as the result of the “class struggle.”

Is this really to be taken seriously?

In his Lectures on Aesthetics, Psychology and Religious Belief, Wittgenstein, discussing Freud’s view that all neurosis in adults is the result of repressed sexual trauma in childhood, states that people have a tendency to believe Freud’s view because it is “charming.” That is, in opposition to Freud’s claim that human beings have an aversion to contemplating his radical theories about human sexuality, Wittgenstein claims that people actually find such “theories” to be quite charming. People want to believe these kinds of “theories.”

Given the worldwide spread of Freud’s unfalsifiable theories, Wittgenstein is, prima facia, correct. Wittgenstein points out that there is a magical feel to such “explanations” because they purport to explain a whole raft of mysterious phenomena by reference to some secret principle that, once articulated, is seen to be self-evidently true. Jones, learning of Freud’s theories concerning sexual repression, says, “It all becomes clear now. The reason I can’t sleep at night has nothing to do with the fact that I dropped out of school because I partied all the time. It has nothing to do with the fact that I can’t hold down a job because I sleep until noon every day. It’s all because I suffered sexual trauma in childhood, where the fact that I cannot remember any sexual trauma in childhood only goes to show how effective the repression really is!”

Wittgenstein holds, transparently correctly, that such (Freudian) theories explain nothing. What they do that makes them so “charming” is to give people a narrative about their lives that they find comforting in certain ways. The same is true of Marxism.

“Original” Marxism literally explains nothing. It certainly did not explain the transition from feudalism to capitalism about which Marx should have been informed. It certainly did not explain the transition from feudalism to socialism by skipping a step in Russia in 1917. It certainly did not explain why the socialist revolution never occurred in England.

What the simplistic Marxist formula about class-struggle does is give people a narrative that provides a comforting meaning to their lives. The fact that members of community X cannot seem to improve their economic lot in life is not their fault. It is not because members of community X tend to drop out of high school at a rate much higher than the general population. It is not because there are few fathers in the home community X. It is not because there is rampant drug use in community X. It is not because community X has babies out of wedlock at a much higher rate rather than the national average. On the contrary, it is because of the “class struggle” that community X is stuck where it is. It is because community X is “oppressed” that it cannot better itself in life.

The fact that some members of community X, in fact quite a lot of them, the ones who finish high school, the ones who do not use or sell drugs, and the ones who do not have babies out of wedlock manage to get into good universities and end up multi-millionaires is not to be mentioned because the vacuity of the Marxist “explanation” is immediately exposed.

In response to all such simplistic explanations, not just Marxism or Freudianism, but even “mechanistic” theories in the philosophy of language that purport to “explain” some vast range of hitherto mysterious phenomena, Wittgenstein, in his “later” period of philosophy is said to have told his friend Drury that he considered using as a motto for his book the sentence from King Lear: “I will teach you differences.”

Wittgenstein explained to Drury that his method is the opposite of Hegel’s. Whereas Hegel always wants to say that things that look different are really the same – his aim is to say that things that look the same are really different. That is, Wittgenstein’s point is that human life is far too multifarious, nuanced, and unpredictable to be explained by such simplistic theories.

Theories like Marxism and Freudianism are comforting because they purport, by means of some simplistic formula, to enable one to escape the mystery and challenges of life. In fact, the problems of human life can be resolved, to the degree that they can be, only by getting into concrete situations and working to resolve them. This is a hard business. There are no guarantees. No one was given an instruction manual at birth that explains what one must do to be successful.

This is the correct intuition behind parts both of “American pragmatism” and “existentialism:” Solving the problems of human life and society will not be achieved by adverting to some “philosophical” theory, but, rather, this essentially requires work, sometimes by trial and error, even working blindly in real world contexts. This is the way the world is. It would be nice if the key to understanding human life and society could be summed up in such a simplistic formula, but, alas, it cannot.

The German “existentialist” and “phenomenologist” Martin Heidegger, in Section 4 of Being and Time, makes an analogous point that is worth explaining: “The question of existence never gets straightened out except through existing itself.” That is, Martin Heidegger, the arch- philosopher, who sat forever in his little shack in the Black Forest filling notebook after notebook after notebook with endless philosophical remarks, is attempting to convey that one does not solve the real problems of existence by philosophizing. Philosophy’s attempt to conceptualize the entirety of life and existence in all its elusive dimensions is a wonderful thing. It is among humanity’s greatest achievements. But do not expect some “philosopher,” whether it be Plato, Hegel, Marx or Heidegger to propound some simple formula (“All human history is the history of class struggles”) that resolves the genuinely hard problems of life, e.g., the problems of economic inequality, mental illness, gender differences and inequities and so on.

The attempt to resolve such problems by citing simple philosophical formulas is, rather, an escape from the problems of life (philosophy as an “escape mechanism”). It is among the greatest of ironies that philosophy, which, ideally, is supposed to help one understand human life, and which, done properly can actually, within limits, do so, can also readily become a means to escape from the challenges of life into simplistic unworldly dreams. As the French existentialist Albert Camus observed in The Rebel, with considerable anguish, “philosophy… can [unfortunately] be used for anything, even for turning murderers into judges.”

10. Marxism Does Not Solve Any Problems

It is a noteworthy fact about Marxists, and others on the Left influenced by Marxism, that faced with a dire social problem, they never seem to take the most direct and obvious ways to solve the problems! Since Marxists do little else but talk about solving social problems, this might seem like an astonishing claim. However, there is a vast difference between talking about solving social problems, or, in the case of Marxists, talking about a future social revolution that will somehow solve them, and actually setting out to solve them.

But before we discuss the Marxist reluctance to solve any actual social problems, it may be useful, by way of analogy, to discuss the difference between the way a “common sense philosopher” like Norman Malcolm (influenced by Wittgenstein and G.E. Moore) attempted to solve philosophical problems, for example, the problem of perception, and the way a great German philosopher like Immanuel Kant approaches such problems. Consider as example the problem how we can know that this little item on the dining room table is a real acorn and not a plastic replica of one.

Malcolm will first look at the contexts in which we say that someone claims to know something about a perceived physical object. He then examines the sorts of things we normally say about the perception of physical objects, including what we say about errors in perception and how we correct mistakes in perception. He then looks at scientific views about the causal relations between physical objects and human observers and asks how we integrate these scientific views with our ordinary views about perception of such objects. Finally, he proposes a certain common-sense solution to the question how we can know that this item on the table is a real acorn and not a plastic replica of one.

The great Kant will not, of course, condescend to do any such thing. Kant wants a revolution (to be more precise, a Copernican Revolution) in the way we think about virtually everything, of which the “solution,” such as it is, to the question how we can know that the object on the table is a real acorn and not a plastic replica of one, is one tiny (vanishing) part.

In order to bring about his “revolution,” Kant distinguishes a plethora of mental faculties, sensibility, understanding, imagination, apperception, judgment, Reason, and a few more that he discovers along his laborious journey, not to mention that he also distinguishes between empirical and transcendental versions of some of these. These are all linked together into a vast system that reaches into virtually all areas of human life, including even religion, morality, aesthetic judgments and the nature of human freedom.

After three Critiques and a plethora of lesser works, and approximately several thousand pages (depending on how one counts) of dense near incomprehensible text, which, he tells us only constitute the “Propaedeutic” to “The System,” not “The System” itself, Kant informs the exhausted reader that the “solution,” such as it is, to the question how one knows that the item on the table is an acorn and not a plastic replica of one requires one to accept the whole system. Nothing less will do because the “System” of human knowledge is an “absolute” unity. One is either all in or not. If you do not accept the whole System there is no helping you.

The present point is that Marx’s “solutions” to social problems are much more like Kant’s “solutions” to conceptual problems than they are like Malcolm’s solutions to conceptual problems, although Kant’s revolution” clearly involves less rioting and bloodshed than Marx’s.

Since both Kant and Marx are German philosophers that worship “The System,” in one or another in the plethora of its “Absolute” but vastly different manifestations, Marxists, like Kant and Hegel, cannot not go directly at the problem. That is the strategy of lesser human beings like Malcolm. Rather, Marx tells us, one cannot really solve the problem per se but must rather bring about a “revolution” that will somehow, in a way specified only in the most general terms, someday “solve” the problem. The communists at the end of history will, in ways we cannot yet quite understand, settle the matter for us once and for all.

To illustrate with a concrete example, consider a Marxist confronted by a community of starving children. The Marxist does not typically propose feeding the children. But not only do Marxists not propose feeding the starving children. They do not even want anybody else to feed them either. Marxists are particularly outraged by the practice of charity, particularly any religious practice of charity, from coming in and feeding the children.

As Cihan Tuğal points out, “The Left usually dismisses charity as demeaning intervention into the lives of oppressed classes, an obfuscation through which exploitation is legitimated. Few arguments by Marx and Engels are as deeply ingrained in Marxism as their statements on charity. [For such traditional conceptions of charity] upheld interdependence between God, the rich, and the poor as sacrosanct.”

That is, for the Marxist, feeding the starving children is “legitimating” the exploitation that led them to starve in the first place. Indeed, Marxists tend to hold that by feeding the starving children one reinforces the denigrating picture of rich people (that would be the capitalists), motivated by their superstitious religious beliefs that were created for no other purpose but to prop up the exploitative capitalist system, pseudo-beneficently swooping in from above to save the starving poor in the name of their illusory tyrannical God, thereby defusing the social pressures that, if allowed to fester, will eventually explode in the glorious socialist revolution. It would be an outrage, and simply will not do, to permit the “oppressors” to solve the problem (feed the children).

In fact, of course, this Marxist view is a cynical caricature of charitable giving. There is literally nothing about charitable giving per se that “legitimates” exploitation. Further, there can be no doubt that many of these starving children will, having been able to survive because of the charitable giving, grow up into careers of their own and work to raise the standard of living in their communities – if, that is, Marxists actually want to solve the problem.

Fortunately, however, one need not stoop to the horror of charitable giving, especially charitable giving by religious organizations, in order to see the way in which the Marxist always prefers some future “revolution” to actually trying to solve the social problems. For, in contrast with the Marxist, the capitalist does directly address those social problems.

Consider again our community of starving people! Rather than attempt to foment a revolution that might, someday, somehow, find a way feed them, the capitalist looks at this community as a possible market. They do a study and conclude that the community can, at its current level of poverty, support one profitable McDonald’s restaurant with about 10 staff (2 managers and 8 helpers).

The McDonald’s is set up and begins operation. Let us suppose that all the managers and staff come from the poor community and that some of the patronage at the restaurant comes from outside the community. After the McDonald’s has been in operation for a few weeks, the community has the same monetary resources it had before the McDonald’s began operation, but now it has in addition the wages of the 10 workers that have been working at the restaurant.

After a sufficient amount of time has passed, another capitalist does another study and concludes that given that its spending power has been increased slightly by the addition of the McDonald’s, this poor community can now also support a profitable gas station that will employ 2 managers and 8 staff. After this gas station has been in operation for some time, the spending power of the community has been increased again due to the addition of 10 new wage earners.

After several more of these small capitalist ventures have added several new small establishments, each with a new group of wage earners, to the community, perhaps a small newsstand, a coffee shop, and a drug store, the number of wage-earners added to the community makes it capable of supporting a much larger profitable operation, perhaps an Olive Garden that employs 10 managers and 40 employees. This kind of establishment can pull in much more wealth from outside the poor community.

The community is, by means of the productive power of the capitalist profit motive, the one to which Marx himself admits extravagant praise, gradually increasing its spending power and standard of living. This will not happen overnight, but in a few decades some of the members of this formerly poor” community will have risen to the point that they can themselves become capitalists who launch additional profitable enterprises in their own community or other poor communities, thereby, step by step, raising the standard of living in those other poor communities as well.

As an aside, this illustrates another false assumption of Marxists, namely that capitalists and workers constitute two exclusive classes, where the one oppresses the other. In fact, in the natural progression of capitalist societies, workers, over some time, can themselves become capitalists and fund new operations that raise the standard of living in their own or other poor communities. The Marxist does not give due regard the fluidity of the two “classes.” It is as if, when an economics textbook distinguishes buyers and sellers, the Marxist forgets that buyers are also sellers.

Let us then suppose that one of these newly emerged capitalists eventually become wealthy enough to buy him or herself a Mercedes, while the other members of the community are by that point still stuck with small inexpensive vehicles. The Marxist or socialist sees this as the establishment of an oppressor class driving fancy cars and an oppressed class still stuck with small unimpressive vehicles.

But this too is a mistake. For someone, to be more precise, a factory (in fact, it will take several factories) of people, will have to build that Mercedes, and additional workers will be needed to service it. It is true that this Mercedes-factory may be in some other community, but since the labor is cheaper in poor communities, this will likely be another poorer community. This means more jobs for poorer communities, which means, in the long run, more spending power in those poor communities. Eventually, some of the sons or daughters of these poor communities will themselves be driving a Mercedes, and when they do, they are not “oppressing” other members of the poor community. On the contrary, they are helping to make it possible for future members of poor communities to raise themselves, over a period of time, to the point that they too can afford a Mercedes.