This month, through the very kind courtesy of St. Augustine’s Press, it is a sheer thrill to present this excerpt from Jeremy Black’s latest book, The Importance of Being Poirot. Make sure to pick up a copy of this fascinating journey through England during the two world wars, and all by way of Monsieur Hercule Poirot, Agatha Christie’s masterful creation.

Black proves himself to be a worthy history-teller because he can aptly “detect” the meaning of stories that seeks to answer the past and guide the present. His erudition runs much deeper than his ability to navigate the stores of resources available on the subject, and the reader gets a glimpse of this early on when in the introduction he proffers his own defense for writing about the importance of a Hercule Poirot.

It all makes for truly fascinating and absorbing reading. Pick up your copy right away! You will not be disappointed.

Here’s a foretaste of what lies in store…

{…} The detective novel, as classically conceived, dates from the nineteenth century, but novels in which detection plays a role have a longer genesis, as even more do stories about crime and detection. Indeed, Simon Brett’s humorous spoof ‘The Literary Antecedents of Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot’ begins with the Anglo-Saxon classic Beowulf (S. Brett, Crime Writers and Other ). This was set in the sixth century, although dates from between then and the tenth.

Moreover, the notion of crime had a moral component from the outset, and notably so in terms of the struggle between Good and Evil, and in the detection of the latter. Indeed, it is this detection that is the basis of the most powerful strand of detection story, because Evil disguises its purposes. It has to do so in a world and humanity made fundamentally benign and moral by God. Thus, as with the Serpent in Eden, a classic instance of malign disguise, Evil seeks to exploit weakness and, to do so, has to lie, or to challenge Good by violence.

These sinister purposes and malign acts are disclosed, at the time or subsequently, and, accordingly, in all religions and religious cultures, tales developed, as did the conventions that affected their contents, framing, and reception. So also did processes to find the truth, some, such as physical trials, extraordinarily rigorous, others, such as the understanding of oracular testament, a challenge of frequently obscure clues that offers much for those interested in Golden Age detective novels in particular. Priesthoods had special functions in discerning, confronting and overcoming Evil, and guidance accordingly, as in confessional handbooks. Campaigns against the menace and deceit of witchcraft saw such anxieties rise to murderous peaks, as in seventeenth-century Europe. This echo of the priesthood as the detector of Evil was seen in G.K. Chesterton’s homely, but clearly moral, clerical detective, Father Brown, who first appeared in print in 1910.

Drawing on the same mental world, a different form of story of detection related to the journey to Salvation, as in John Bunyan’s epic The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678), as individuals had to detect snares en route. In part as a result, there was a clear overlap between writing about this world and the next, the struggle with Evil being foremost. John Buchan used the Bunyan epic in his Mr Standfast (1919), a World War I story in which a German agent in Britain is a major threat and needs uncovering and vanquishing.

The development of the novel in England in the eighteenth century saw the notion of secrecy pushed to the fore, with an opening up of such secrets being a key theme in the plot of many novels, secrets related to behaviour, as in the exposure of hypocrisy, or to origins. This could be in a comic context and to comic effect, as in Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones (1749), with the unveiling of his parentage; but there were also novels that were darker and more troubling. This style came to the fore with the Gothic novels of the late eighteenth century, notably those by (Mrs) Ann Radcliffe, especially The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) and The Italian (1797), and also Matthew Lewis’s The Monk (1796). These novels had elements of both the thriller and the detective novel. The fears to which they could give rise could be a source of fun, as was clearly with Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey (1817), but the popularity of Gothic fiction is instructive.

{…}

The moral framework of any society is one we need to consider when assessing literature as a whole, and fiction in particular, because in fiction it is possible to alter the story to drive home a moral lesson, a method that is not so simple when dealing with fact. Thus, we need to consider the changes in religious belief and sensibility in this period. Despite Murder in the Vicarage (1930), At Bertram’s Hotel (1965), and several other appearances, clerics do not play a major role in Christie’s novels.

Nevertheless, in Three Act Tragedy (1934), there is a positive account of Christianity from the dynamic young Egg Lytton Gore referring to a recently dead clergyman.

‘…He prepared me for confirmation and all that, and though of course a lot of that business is all bunkum, he really was rather sweet about it…. I really believe in Christianity – not like Mother does, with little books and early service, and things – but intelligently and as a matter of history. The Church is all clotted up with the Pauline tradition – in fact the Church is a mess – but Christianity itself is all right … the Babbingtons really were Christians; they didn’t poke and pry and condemn, and they were never unkind about people or things’.

Canon Prescott, in A Caribbean Mystery (1964), is positive. In a gentler age, it was possible to say that Prescott is extremely fond of children, especially small girls, without that being seen as sinister.

Moreover, even though clerics are not thick on the ground, that does not mean that religion is absent, either in terms of the lay religiosity of the characters or with reference to the role of the author. Far from it. A similar discrimination to that of Egg Lytton Gore, in favour of a true Christianity as the basis for judgment, is offered in Christie’s Appointment With Death (1938), when Sarah King observes in the symbolic setting of Jerusalem:

‘I feel that if I could sweep all this away – all the buildings and the sects and the fierce squabbling churches – that I might see Christ’s quiet figure riding into Jerusalem on a donkey – and believe in him’.

This leads Dr Gerard to reply gravely: ‘“I believe at least in one of the chief tenets of the Christian faith – commitment with a lowly place”’. He goes on to claim that ambition is responsible for most ills of the human soul, whether realised or not. Asylums are filled, he argues, with those who cannot cope with their insignificance.

In a way, Christie presents murder in the same way, and the implication throughout is that it defies the true message of Christianity, not least the acceptance of suffering and the significance of the soul. Some ghost stories, for example those of M.R. [Montague Rhodes] James (1862–1936), explored similar themes. At the close of In Search of England (1927), H.V. Morton meets a vicar who tells him:

‘We are, in this little hamlet, untouched by ideas, in spite of the wireless and the charabanc. We use words long since abandoned. My parishioners believe firmly in a physical resurrection. … We are far from the pain of cities, the complexities … We are rooted in something firmer than fashion’.

In Three Act Tragedy (1934), the disabled Mrs Milray refers to ‘“The Lord’s will”’. At the denouement, there is also a social dimension, one that Christie brings up when Sir Charles Cartwright responds to Poirot: ‘He radiated nobility and disgust. He was the aristocrat looking down at the ignoble canaille.… Hercule Poirot, the little bourgeois, looked up at the aristocrat. He spoke quietly but firmly’. Speaking truth to power, or rather to social eminence and fame, Poirot is observed as taking a moral line, both in stopping murder and also in thwarting a would-be bigamist. The dubious morals of much of the ‘smart set’ have recently been highlighted in the 2021 first volume of a projected complete edition of the diaries of ‘Chips’ Channon. Poirot is more generally against crime, in The ABC Murders comparing murder to gambling. In ‘The Chocolate Box’ (1924), Poirot’s sole professional failure, he refers to himself as being ‘“bon catholique”’.

Religion is present again in Triangle at Rhodes (1937). Poirot goes to the Mount of the Prophet where he meditates on God permitting ‘himself to fashion certain human beings’ and advises Marjorie Gold to ‘leave the island before it is too late’, a moment recalled in the closing lines when he refers to being ‘on the Mount of the Prophet. It was the only chance of averting the crime… she chose – to remain…’ Thus, Poirot as prophet, and Gold as the sinner with free-will, who has rejected, through pride, the possibility of safety, are clearly revealed, with the message underlined in case the reader has missed it. Furthermore, as another aspect of morality, Poirot is convinced that, if the wicked escape, as in the case of ‘The Mystery of Hunter’s Lodge’ (1923), it is at a price. In that story, and the capitalisation is in the original, the murderers gain the huge fortune of the victim, Harrington Pace, but Nemesis overtakes them. They crash in an aircraft and Justice is satisfied. In the penultimate scene in Death on the Nile (1937), Mrs Allerton and Poirot join in thanking God that there is happiness in the world. Earlier in that novel, Poirot has referred to a parable in the Bible when chiding Linnet Ridgeway.

Reference to God is part of everyday conversation; as in Murder Is Easy (1939) when Mrs Pierce reflects on the death of her young Emma Jane: ‘“a sweet little mite she was. ‘You’ll never rear her’. That’s what they said. ‘She’s too good to live’. And it was true, sir. The Lord knows His Own”’. However, in the same novel there is bitter criticism of the pompous press magnate, Lord Whitfield, who has a great faith and trust in Providence, with enemies of the righteous (the latter a group with whom he identifies) struck down by swift divine wrath. Luke Fitzwilliam finds excessive Whitfield’s retribution on the drunken chauffeur, and Whitfield’s comparison of himself with the Prophet Elisha is obviously inappropriate. Christie is clearly with Fitzwilliam, although, in a typical case of misdirection, the proud and pompous Whitfield is not in fact the villain.

The references to religion continue. N or M? (1941) takes its title from a catechism in the Book of Common Prayer, while in Evil Under the Sun (1941), Stephen Lane, a cleric, complains that ‘“no one believes in evil”’, whereas he firmly sees it as a powerful reality that ‘“walks the earth”’. Poirot agrees with this longstanding view. In Destination Unknown (1954), the villainous impresario of evil evades justice on earth, but Jessop comments ‘“I should say he’ll be coming up before the Supreme Justice before very long”’. The link between crime and evil is thus reiterated. Very differently, the continuity of ordinary Christian society is presented as significant in A Caribbean Mystery (1964), in which Inspector Weston of the St Honoré CID notes that there are few marriages on the island, but that the children are christened.

A practising Anglican, Christie was far from alone as a detective novelist with a strong religious sensibility. Others of this type included Freeman Wills Croft, as in Antidote to Venom (1938). The detective fiction of the period presupposed a providentially governed universe that could provide meaning. This was a key aspect of the religious necessities of such fiction and of the contemporary reporting on crime. At the same time, standards were more general. Thus, the world of Sherlock Holmes required a very striking stability so that clothes, routines, and other factors had a fixed and knowable meaning. These ideas of order, epitomised in character and behaviour, were an aspect not only of particular detective novelists, such as Dorothy L. Sayers, but also of the genre as a whole and, indeed, of social norms and practices.

Christie did not restrict her morality to crime. ‘Magnolia Blossom’, a magazine story of 1925, was not a crime piece but a three-way drama of a marriage under strain and of how people react. The role of the author in terms of judgment is not of course synonymous with the life of the author. It is well-established that some of the great detective writers had somewhat rackety personal lives (Edwards, The Golden Age of Murder). Yet, that rarely stops moral grandstanding or indeed simple conformity. And so with detective fiction, much of which relates to morality, directly or by reflection, and with both the author and the reader offering moral frameworks. Indeed, in one respect, fiction is an attempt to offer guidance in a post-Providential world. In an urgently-religious age, Providence brings an instant fate to the wicked, but, by the 1920s, the religious environment was somewhat different. Judgment in life came to be seen more as a matter of human agency and agencies, and the detective was to the fore. Yet, there could be a religious aspect to the moral dimension, a perspective vividly demonstrated in J.B. Priestley’s play An Inspector Calls (1945), a haunting drama of discovery.

Christian morality is applied by Christie in part in terms of the newlyfashionable psychological insights and in terms of the belief in heredity Poirot mentions in ‘The King of Clubs’ (1923), and in which he follows other detectives including Holmes. These insights provide both a subject for discussion and explanation and a particular modus operandi for Christie and her detectives. This is true not only of the ‘foreign’ Poirot, but also, albeit using a different language, the very English Jane Marple, who is first introduced in ‘The Tuesday Night Club’, a thoughtful short story of December 1927. In The ABC Murders, Poirot insists that it is crucial to treat the murderer as ‘“a psychological study”’ and ‘“to get to know the murderer”’. Subsequently he adds, ‘“A madman is as logical and reasoned in his actions as a sane man – given his peculiar biased point of view”’. Cards on the Table (1936) also sees an emphasis on the psychology of the suspects, which is a theme underlined in Christie’s Foreword. A total misunderstanding, one that is all-too-typical of responses by critics, was offered by Camilla Long in a television review in the Sunday Times on 16 February 2020 in which she claimed: ‘Christie didn’t do personalities; she felt any hint of psychology could distract from the plot lines’.

So also for others. In Three Act Tragedy, Lady Mary Gore, who, in a Christie-like autobiographical touch, had fallen for ‘a certain type of man’, foolishly thinking ‘new love will reform him’, explains to Satterthwaite that:

‘Some books that I’ve read these last few years have brought a lot of comfort to me. Books on psychology. It seems to show that in many ways people can’t help themselves. A kind of kink…. It wasn’t what I was brought up to believe. I was taught that everyone knew the difference between right and wrong. But somehow – I don’t always think that is so’.

Satterthwaite adds that: ‘“Without acute mania it may nevertheless occur that certain natures lack what I should describe as braking power… in some people the idea, or obsession, holds”’. In ‘The Red Signal’ (1933), Sir Alington West, ‘the supreme authority on mental disease’, explains: ‘“suppression of one’s particular delusion has a disastrous effect very often. All suppressions are dangerous, as psychoanalysis has taught us”’.

The methodical and intelligent Superintendent Battle, who first appeared in The Secret of Chimneys (1925), acknowledges a debt to Poirot’s psychological methods in Towards Zero (1944). The language varies, but the theme is constant. In Death in the Clouds (1937), the young Jane Grey challenges the ‘“very old-fashioned idea of detectives”’ as involving disguise (as Holmes had done), as nowadays they simply think out a case psychologically.

Christie was far from alone in her interest in psychology. Thus, in The Mystery of a Butcher’s Shop (1929), Gladys Mitchell, who was up on Freud, introduced as her detective Mrs Beatrice Bradley, the author of A Small Handbook of Psycho-Analysis. Yet, Christie had a much more Christian feel for psychology. At the brilliant end of Crooked House (1949), where there is one of the more outstanding reveals, there is a psychoanalytic explanation in terms of ‘retarded moral sense’ and heredity, including of ‘ruthless egoism’. More bluntly, this becomes “There is often one of the litter who is ‘not quite right”’, and Christian judgment and justification are offered: ‘“I do not want the child to suffer as I believe she would suffer if called to earthly account for what she has done…. If I am wrong, God forgive me… God bless you both”’. In Hallowe’en Party (1969), Mrs Goodbody, the very pleasant local witch, or, at least, fortune-teller, is clear on the real presence of evil:

‘wherever you go, the devil’s always got some of his own. Born and bred to it … those that the devil has touched with his hand.

They’re born that way. The sons of Lucifer. They’re born so that killing don’t mean nothing to them … When they want a thing, they want it… Beautiful as angels, they can look like’.

Mrs Goodbody contrasts this with black magic: ‘“That’s nonsense, that is. That’s for people who like to dress up and do a lot of tomfoolery. Sex and all that”’. At the same time, Honoria Waynflete, in Murder is Easy, is compared to a goat which is presented as an apt symbol of evil, as also in Miles Burton’s The Secret of High Eldersham (1931). In Honoria’s case, her behaviour is discussed as an instance of the touch of insanity allegedly present in old families, and she is definitely seen as unhinged. Being a ‘“wrong ’un”’ is the problem for Roger Bassington-Ffrench in Why Didn’t They Ask Evans? (1934).

Although there was no equivalent to Doyle’s strong interest in Spiritualism, the occult plays a role with Christie, one that is understated in television treatments. ‘The Harlequin Tea Set’ (1971) very much offers the idea of the mixing of this world with a spirit world, as the dead Lily joins Harley Quin from the other world to help Mr Satterthwaite protect the living in a combination that Christie described in her autobiography as her favourite characters. So also with the protection of many ghost stories both of this period and of earlier ones, such as those of Sheridan Le Fanu (1814–73). An altogether more menacing moral framework is on offer in Christie’s The Hound of Death (1933). The occult is to the fore in this mysterious and disturbing tale of an alternative ‘Brotherhood’, but a moral retribution is delivered on the vulpine Dr Rose. The hound is very different from that of the Holmes story about the Baskervilles, while in the title-story of the collection there is a religious dimension not present in the latter.

Not black magic, but a good equivalent, can be deployed, as with the kindly nurse in Towards Zero (1940) who comes from the West Coast of Scotland where some of her family had ‘the sight’ or ‘Second Sight’. Possibly because the nurse, like Christie, can see what will occur in the novel, she tells the suicidal Angus MacWhirter that God may need him, and is proven correct.

In many respects, Christie adapts psychological views to match Christian morality. That itself may appear to be one answer, but it is not so, for on matters such as free will Christianity offers a range of explanations. As a consequence, Christie’s work can in part be seen as an aspect of debate within inter-war Christianity, including English Christianity. In A Pocket Full of Rye (1953), the Calvinistic, very elderly Miss Ramsbottom, who is committed to missionary work as the ‘“Christian spirit”’, refers to Marple as ‘“frivolous, like all Church of England people”’. Christie was Church of England. Alongside Poirot’s concern for psychoanalysis, there is Marple’s blunter focus on, and denunciation of, wickedness, one that is more to the fore than with most of the clerical detective novelists of the period such as Ronald Knox and Victor Whitechurch: they generally left their cassocks at home. In A Pocket Full of Rye, Marple remarks ‘“This is a wicked murderer, Inspector Neele, and the wicked should not go unpunished”’, and Neele replies ‘“That is an unfashionable belief nowadays. Not that I don’t agree with you”’. Christie is speaking through both of them.

Aside from wickedness, the frequency with which murderers are castigated for ‘conceit and self-confidence’, as in The ABC Murders, is instructive. In that novel, Poirot seeks to psychoanalyse and profile the murderer after his first murder:

‘In one sense we know nothing about him – in another sense we know already a good deal…. A great need to express his personality. I see him as a child possibly ignored and passed over – I see him growing up with an inward sense of inferiority – warring with a sense of injustice – I see that inner urge – to assert himself

– to focus attention on himself ever becoming stronger …’

This approach is very deliberately contrasted with what is presented as a Holmesian one; although Sherlock also relied heavily on pre-Freudian psychology. This is to a degree that not all television and film versions of Poirot stories have fully represented. The point is very much driven home in ‘The Plymouth Express’ (1923), with the emphasis for Poirot on psychology, and not ‘scene of the crime’ footmarks and cigarette-ash. Inspector Japp, in contrast, focuses in this story on finding clues along the route. Based on Lestrade, Japp was introduced in the Mysterious Affair at Styles and appeared in seven Christie novels, always alongside Poirot, finally appearing in One, Two, Buckle My Shoe (1940); although being mentioned thereafter. In The ABC Murders, Poirot jests with Hastings:

‘The crime was committed by a man of medium height with red hair and a cast in the left eye. He limps slightly on the right foot and has a mole just below the shoulder-blade’.

… ‘For the moment I was completely taken in’.

‘You fix upon me a look of dog-like devotion and demand of me a pronouncement à la Sherlock Holmes … it is always the clue that attracts you. Alas that he did not smoke the cigarette and leave the ash, and then step in it with a shoe that has nails of a curious pattern’.

In ‘The Kidnapped Prime Minister’, Poirot, to the anger of all, refuses to leave Boulogne to search for clues to the kidnapping such as tyre marks, cigarette-ends, and fallen matches because he must focus on a logical solution, which he does successfully. Similarly, in Death on the Nile, the murderer, as Poirot notes, is not so obliging as to drop a cuff link, a cigarette end, cigar ash, a handkerchief, lipstick, or a hair slide. Instead, in a comparison that would have come naturally to Christie, Poirot compares himself to an archaeologist clearing away the extraneous matter. This involves, as he notes in Mrs McGinty’s Dead (1952), using a hunting image, starting, as it were, several birds in a covert, as if seeking to create a form of creative disruption that will lead to the revelation of the truth. The misdirections provided through, and by, possible culprits are a form of this creative disruption as well as a response to it.

In practice, Christie offers a degree of caricature, as the Holmes stories include psychological insights, but she is correct to draw attention to a contrast. And not always simply with the detective. In ‘The Market Basing Mystery’ (1923), Dr Giles tells Japp that he cannot give the time of death to an hour as ‘“those wonderful doctors in detective stories do”’.

And so also with other novelists. In J. Jefferson Farjeon’s Seven Dead (1939), Inspector Kendall, a figure of brusque intelligence and determined drive, remarks, ‘“When you don’t play the violin, or haven’t got a wooden leg, smartness is all you’ve got to fall back on”’, and says of Inspector Black: ‘“a good man. He doesn’t play the violin, either, or quote Shakespeare”’.

In a conversation in The Clocks (1963), not one of Christie’s better novels, Poirot gives Colin Lamb a long account of what he likes in ‘“criminal fiction”’. Anna Katharine Green’s The Leavenworth Case (1878) is praised for ‘“period atmosphere … studied and deliberate melodrama”’ and ‘“an excellent psychological study”’ of the murderer. Poirot then moves on to Maurice Leblanc’s The Adventures of Arsene Lupin (1905–7), which he finds preposterous and unreal, but also as having vigour and humour, which is indeed the case. Gaston Leroux’s The Mystery of the Yellow Room (1907–8) is approved of from start to finish, not least for its logical approach. Charges that the novel is unfair are dismissed as there is truth concealed by a cunning use of words, which is very much Christie’s technique. Poirot notes that that masterpiece is now almost forgotten. The selection Christie offers in the account is scarcely insular, nor the approach xenophobic.

{…}

International malice and domestic conspiracy is an important context for some of Christie’s early work, and to this we will turn shortly. There is no but here, for categories overlapped, strands interacted, and there was no tightly defined set of parameters. Yet it is also important to see Christie in terms of the strength of a middle-brow reading public who wanted good stories and found detective fiction an established means to that end. This public was the key to the genre. At the same time, what this interest would mean in the post-war world was unclear, and authors developed their characters, plots, and styles, in the context of probing a readership that was resetting after that cataclysmic conflict.

And that probing was necessary in order to earn money, as Christie recorded making only an advance of £25 from The Mysterious Affair at Styles, and that from a half share of the series rights which were sold to The Weekly Times. Her novel, however, had introduced two stars, herself and Hercule.

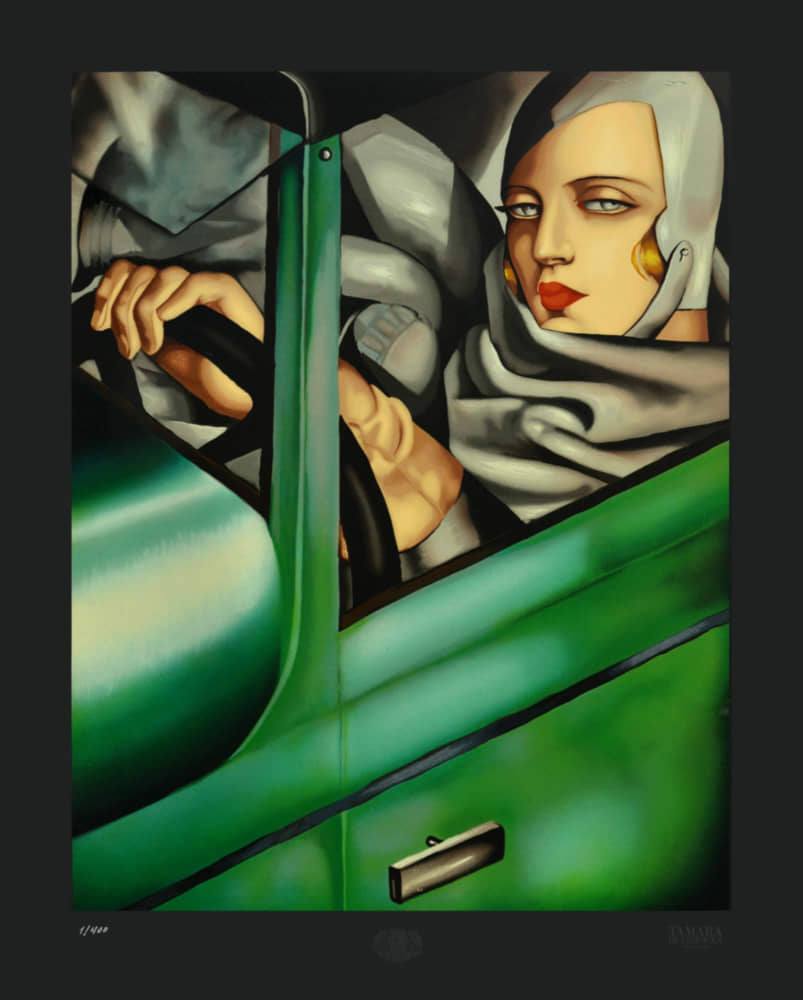

The featured image shows, “Autoportrait (Tamara in a Green Bugatti,” by Tamara de Lempicka; painted in 1925.