Me And Pop

No, the articles by Mark Stocker that will dominate 2022 and surely represent the highlight of the Postil Magazine to its more discerning readership, are not about the author and the generally benign relationship he enjoyed with his much loved, late father.

Pop was a square about Pop—his idea of a great number one hit was the theme from The Third Man—I ask you—and his comprehension of heavy metal was minimal. That said, Oliver Stocker could be quite shrewd. Watching Mick Jagger on our Bush black and white television, a masterpiece of c. 1960 cabinetry, he pronounced: “That young man is interesting looking and has real presence. I predict a big future for him.”

I was a little disconcerted, for what right had someone of the older generation to comment in any shape or form upon “my” Mick? Such was my admiration for him that when I read in Fabulous magazine that he disliked tomatoes, I too boycotted them for a couple of weeks.

All this testifies to the place that music of the popular idiom had in my formative years. I am indeed “Talking about my generation” to quote Pete Townsend. I entered my picture of his group (as they were then called) The Who in the 9-12 year old section in the 1966 Window magazine art competition for children of civil servants at the Department of Social Security (where Oliver Stocker worked in the Legal Office) and attained second prize: a proud line in my CV. I think some messily painted family dog beat me to it, but I feel remarkably little bitterness. More to the point, pop music exuded from my every breath and pore….

As I pen these columns, memories are brought back and I feel the corresponding need to share them with my devoted readers. The undertaking is both profoundly intellectual (this can be easily inferred through my multiple literary and historical allusions), and unashamedly emotional. Indeed, I think of Carpenter (Karen, not Edward, you clot) when she reminisces:

When I was young

I'd listen to the radio

Waitin’ for my favourite songs

When they played I’d sing along

It made me smile.

Those were such happy times

And not so long ago

How I wondered where they’d gone

But they’re back again

Just like a long lost friend

All the songs I loved so well.

Every Sha-la-la-la

Every Wo-o-wo-o

Still shines

Every shing-a-ling-a-ling

That they’re startin’ to sing’s

So fine.

Pure poetry, and beautifully enunciated singing. Reader, I will take you on a journey through “Every Sha-la-la-la/ Every Wo-o-wo-o” in these columns in the months ahead, and I thank you in anticipation for joining me. I prefer to keep the contents a closely-guarded secret, and the editor agrees, but I promise to explore a diversity of genres (I’m very PC, you see). Sometimes an arresting theme transcending them, such as “Pop and politics” and “Pop art,” will be my focus.

Throughout, I must acknowledge with warm thanks the patient and sagacious comments and corrections of Emeritus Associate Professor Robert G. H. Burns, a bass-guitarist’s bass guitarist and author of Experiencing Progressive Rock: A Listener’s Companion (2018). Impressed? I am, for starters. Well, without further ado, let us commence.

In this inaugural article, I consider three solo male singers who came to the fore in the 1960s, all of whom had an impact on me. Read on, and—aided by Youtube—appreciate how and why, and see if you feel similarly…

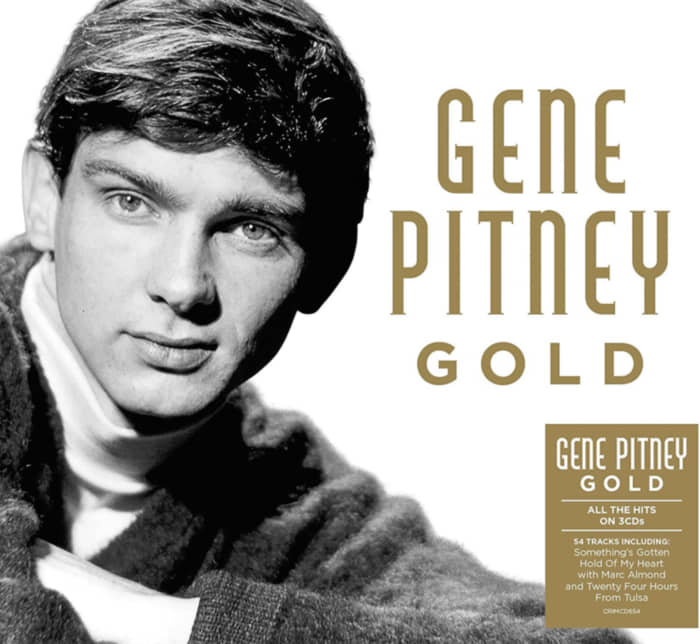

Let’s start with Gene Pitney, who was in the British Top Ten when I became instantly hooked on pop aged nearly eight. My moment of epiphany dates from the first ever episode of Top of the Pops, January 1964, presented by the egregious Jimmy Saville. I remained a TOTP addict up to its 500th edition (1973) but David Cassidy’s nauseating “Daydreamer/ The Puppy Song” was the limit, and I never watched a single episode thereafter. Gene’s current hit marked his British breakthrough, the splendid Bacharach-penned “24 Hours from Tulsa”:

It wasn’t so much a song as a short story. Gene was one day away from the arms of his girlfriend when he met this smashing babe, you see, and this is his confessional. What impressed me was the perfect consonance between the tone and timbre of his unusual tenor voice and his guilt-ridden state. A lot of Gene Pitney is pretty emotional stuff, dim critics would say faux melodramatic, on the verge of operatic, with a tenor that sometime barked with angst.

The tragedies of love central to the Pitney iconography were belied by what was evidently a happy, if sadly shortened, life: his wholesome looks, his invariably gentlemanly nature shown to what must have been many limited and irritating fans, his unaffected Anglophilia and his regular family life (marrying his high school sweetheart after briefly dallying with Marianne Faithfull, a fortunate escape). What clinched it for me, though, was the teenage Gene (and I hope beyond) as a keen coin and fossil collector. A punk rocker would doubtless deem Pitney a fossil, but that’s rude.

Once when I saw Henry Moore being interviewed on TV, I was initially irritated by, then suddenly grasped, why he appeared to be fidgeting all the time: he’d much rather be in the studio, modelling material than being browbeaten by some art historian. With Gene you get a comparable impression: he’d much rather be singing than doing anything else. Exploring his repertoire on YouTube shows something far wider than anything I had expected: put the phone book in front of him and Gene would happily sing it. My favourite songs are often the very early ones: a teen Gene (well, barely out of them) was perfectly cast with Dimitri Tiomkin’s eerie “Town without pity”:

He’s almost as impressive with the upbeat Jagger/Richards “That girl belongs to yesterday.” He’s typically moody in the anthemic “I’m gonna be strong,” which certainly made big girls cry. He sings a shampoo commercial in “She lets her hair down.” With “24 Sycamore,” he glories in unglamorous British semi-detached mock Tudor suburbia. But he’s utterly captivating—and if I may say so, totally Stocker-like—when, relatively late in life, he turned to singing John Betjeman’s poem, “Myfanwy at Oxford”:

Pink may, double may, dead laburnum

Shedding an Anglo-Jackson Shade,

Shall we ever, my staunch Myfanwy,

Bicycle down to North Parade?

Kant on the handle-bars, Marx in the saddlebag,

Light my touch on your shoulder-blade.

This is 24 light years from Tulsa but it’s the same irrepressible Pitney. After she’d written her superb double biography of John and Myfanwy Piper, I drew Frances Spalding’s attention to this recording and her response was “I just don’t believe this!”

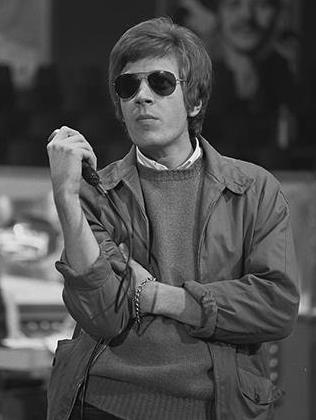

Scott Walker: an act of sheer class, and he damn well knew it. Calling his first four albums Scott 1, Scott 2, etc. shows that he had no false modesty. He had a musical depth and refinement that I recognise the more amiable Gene lacked, and, not surprisingly, enjoyed a more respectful critical press.

Pseuds particularly admire the experimental Scott Walker of the last 20-30 years of his career; but these impenetrable records sold pathetically and their titles say it all: “Track Three” (akin to the modernist “Untitled”) and “Bish bosch”—give me a break! But much earlier he had the nous, and indeed the talent, to forsake the heart-throb status of his first incarnation as lead singer of the Walker Brothers, who were in their heyday between 1965 and 1967. What I loved about their hits was not just their melodies, impeccable delivery and powerful orchestration, but their emotional generosity. The first verse of “Love her” reads thus:

Love her

and tell her each day

that girl needs to know

tell her so, tell her everything I couldn't say

Like she's warm, and she's sweet and she’s fine,

Oh love her like I should have done.

From beginning to end (the Ronettes’ cover, “Walking in the Rain”), the Walker Brothers were something special. But Scott was bursting to break free, to go up-market. It was a golden time, before the cult of the singer-songwriter which did untold damage to pop and rock (can you imagine Enrico Caruso or Kiri Te Kanawa as composers?) and when an artist was given free rein to choose their own material and not kowtow to mega-capitalist labels and ghastly managerial suits. Scott’s selection of songs has impeccable taste and deftly straddles genres. With the big ballad “Angelica,” he makes a fascinating comparison with Pitney:

Scott’s version is richer and more classically perfect but Gene wins the contest emotionally. Yet Scott made a dear friend (now sadly dead) cry when I sent her “Best of both worlds.” He can do a great Jacques Brel in “Jackie,” and a comparably impressive Tim Hardin in “Black Sheep Boy” and “The Lady Came from Baltimore”:

Yes, a bit soundalike those two, but gorgeously melodic and they don’t outstay their two-minute welcome. With “The Big Hurt,” Scott veers towards soul, but you’d never find him being danced to on the talced floor of the Wigan Casino.

“Scott 4,” alas, flopped and this setback set him on a new path of becoming ever more relentlessly experimental. It was brave but—unlike Philip Guston in painting—ultimately regrettable. Battling with his later material, I felt like screaming, “Oh Scott! Have you changed your name to Scotthausen?”

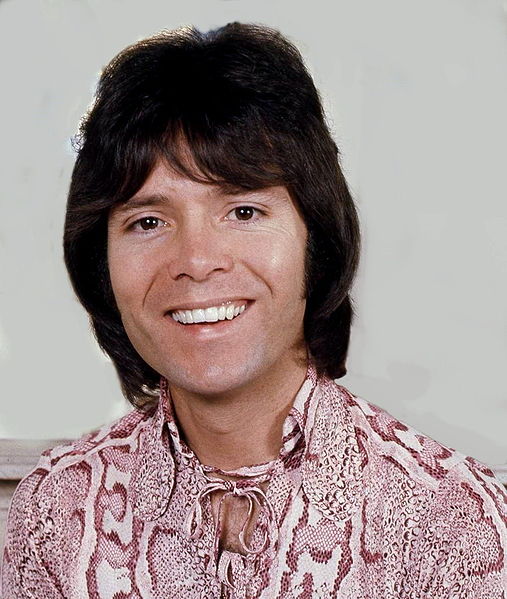

Cliff Richard, the “Peter Pan” of British pop, who never really made it in the US, is hard to write about. I champion him partly because he has long been the object of vicious, sneering, sniping criticism by critics and journalists with intellectual pretensions. I ask them this: isn’t his Christ-centred life (not one I’d choose, but…) a saner, better role model than that followed by his tragic near contemporaries Jim Morrison and Janis Joplin, as well as by improbable survivors like his dissolute near namesake Keith Richards?

Yes, there’s a lot of light-weight froth in Cliff’s vast repertoire and—good god—he has suffered for this (“Goodbye Sam, Hello Samantha” is an especially toe-curling example). At the same time, there’s also a fair bit that’s good, occasionally damn good. Cliff is so old, he long predates this recent pensioner, and I have to delve back to my pre-Top of the Pops infancy for some of his best songs: it’s hard to get past “Living Doll,” written in 10 minutes by Lionel Bart:

Then there’s the irrepressibly catchy “The Young Ones,” “Summer Holiday” and “Bachelor Boy.” A measure of Cliff’s appeal was when I was in a supermarket fairly recently and their canned music system was playing his early, and still spiritedly rocking, “Please don’t tease.” A little boy was shopping nearby and asked “Mum, what’s that song called?”

“Congratulations,” cheated by an unholy fascist alliance of Spain and Portugal out of winning the 1968 Eurovision Contest by a song that repeats “La-la-la-la” no less than 138 times, remains the YouTube number I send to friends who attain high places or have grandchildren. They seem to approve. You need stronger nerves to cope with Cliff’s remarkable 1999 “Millennium Prayer,” which infuriated his snobbish atheistic critics by setting the Lord’s Prayer to the song of “Auld Lang Syne”:

It was cheeky, it was naff, but you have to hand the concept to its composer, and it is nothing if not a conviction performance by Cliff. He enjoyed the last laugh over the knockers, as the great British public promptly sent it to Number One, the fourteenth in his phenomenal career.

And then, rather too rarely, Cliff records songs that are to my untutored ear, lovely standards. I’m a soft touch for his European composed ballads—the wistful and tender “Constantly” and the melodic “All my love”:

“When in Rome” is a remarkably good and as ever, critically underrated album of the mid-1960s. He goes reggae in a sentimental but effective cover of Harry Belafonte’s “Scarlet Ribbons” (avoid the tacky video, however), and is impressively Country in “Wind me up” and “The minute you’re gone,” recorded in Nashville. Cliff won the reluctant admiration of some of his sharpest critics with his so-called “Renaissance” phase (the early to mid-1970s hadn’t been particularly kind to him), with “Devil Woman,” “We Don’t Talk Anymore” and, particularly, “Carrie”:

Written by B.A. Robertson, a very different kind of artist, “Carrie” was justly admired by AllMusic pundit Dave Thompson as “an enthrallingly atmospheric number. One of the most electrifying of all Cliff Richard’s recordings.” Cliff is no social commentator, but this came closest to nailing the increasing anomie and alienation of British society in the early Thatcher era. He is trying to track down the young woman of the title, but is told:

Carrie doesn’t live here anymore Carrie used to room on the second floor Sorry that she left no forwarding address That was known to me. So, Carrie doesn’t live here anymore You could always ask at the corner store Carrie had a date with her own kind of fate It's plain to see. Another missing person One of many we assume The young wear their freedom Like cheap perfume.

This is an unhappy real-life situation, really rather banal and almost certainly one of underlying tragedy, but the whole point is we can at once hear it and identify with it. Cliff’s quest culminates in a helpless, inarticulate, despairing “Carrie!” I love the muffled sound effects of the unhelpful information line. Don’t bother listening to Cliff Richard if you seek anything profound, but do so if you want a singer who—perhaps despite yourself and your Guardian-reading proclivities—can and indeed should sometimes move you.

Mark Stocker is an art historian whose recent book is When Britain Went Decimal: The Coinage of 1971.

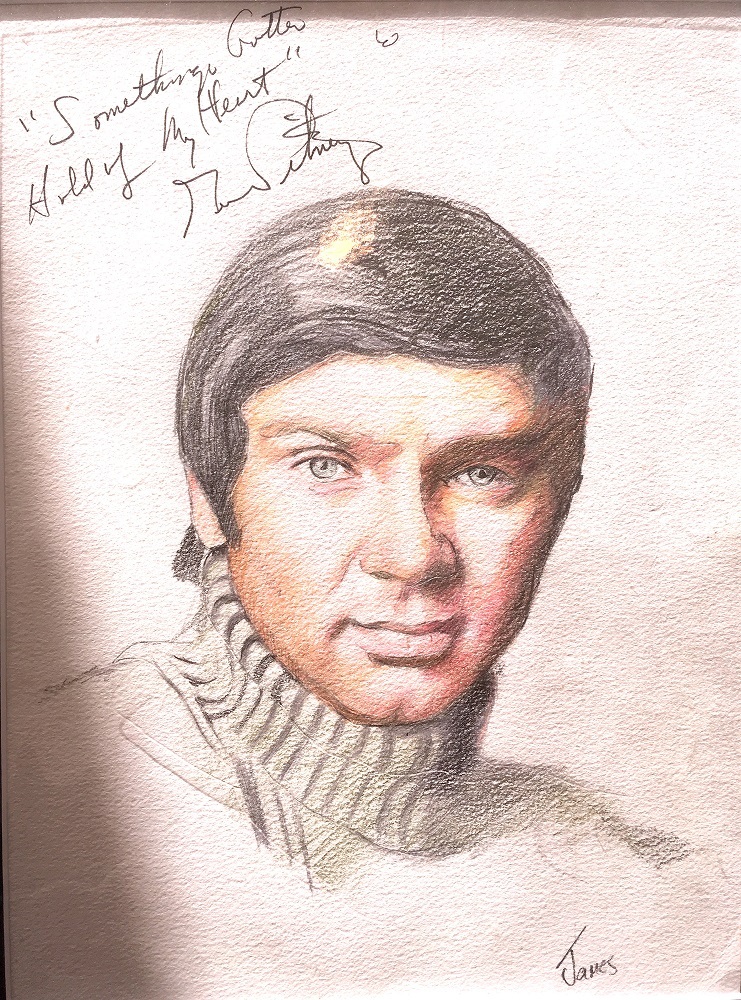

Featured image: a portrait of Gene Pitney by James Wilkinson, ca. 1980s.